| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XXI TAHITI, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, SAN FRANCISCO Tahiti — Voyage to Hawaiian Islands — Oahu, with its capital Honolulu — Visit to Island of Hawaii — San Francisco — The Author returns to England. TAHITI Wallis is the first

European known certainly

to have seen Tahiti. He visited it in 1767, and was followed two years

later by

Cook. The predominant chiefs on the island at this time were Amo and

his wife

Purea, of the district of Paparo on the south coast. They are chiefly

notorious

as the founders of the great maræ — or "temple" — of Mahaiatea, which

they built in honour of their infant son, Teriiere. This work must have

been in

progress when Wallis anchored on the other side of the island. The

demands

which they made on their fellow natives in order to secure its erection

were so

extortionate that a rising took place against them; and by the time

Cook made

his first appearance they were shorn of much of their glory.

Subsequently

various other navigators visited the island. Cook anchored there a

second time,

and H.M.S. Bounty made a prolonged sojourn.

In 1797 thirty missionaries arrived, sent from England by the London

Missionary

Society. By this time another native

family was in the

ascendant, whose territory was on the north coast. They have become

known as

the Pomare, a name crystallised by the missionaries, but which was in

reality

only one of the minor appellations which had been adopted, native

fashion, by

the chief of the day. Pomare II. was baptised in 1819. About forty years later

Roman Catholic

missionaries arrived, and a struggle for ascendancy took place between

them and

the London Society. The Home Government refused to support the

Protestants.

Queen Pomare IV., therefore, though she much preferred the English, was

compelled to apply for a French protectorate, which was established in

1843. On

the death of the old Queen in 1877, the French recognised her son,

Pomare V.,

who had married his cousin Marau. The new Queen was the daughter of a

chiefess

known as Arii Taimai, who had married an English Jew named Salmon.1

Miss Gordon Gumming, who visited the island at the time, gives an

interesting

account of the procession round the island to proclaim the new

sovereigns, in

which she herself took part. In 1880 Pomare handed over his claims to

the

French Government, by whom the island was then formally annexed. We

sighted Tahiti on the i6th of September, 1915, sailed along its coast

with

interest, and anchored in the afternoon at Papeete on the north shore.

It was

wonderful to return once more to the great world, even in its modified

form at

Tahiti, and the Rip van Winkle sensation was most curious. The Consul,

Mr. H.

A. Richards, was early on board with a kind welcome, and sent us round

the

longed-for sacks containing a year's accumulation of letters and

newspapers.

The mail, however, brought bad personal news, and though life had to go

on as

usual, recollections of the island have suffered from every point of

view.2 Tahiti,

as seen from the sea, with its mass of broken mountains covered with

verdure,

is undoubtedly very beautiful; and the sunset effects over the

neighbouring

island of Moorea are particularly striking. The lagoon too is

fascinating, and

refreshing expeditions were made in the motor launch to study the

wonders of

its protecting coral reef. When on land, however, the charm of the

island is

somewhat dissipated. The inhabited strip round the coast, which varies

from

nothing up to some two miles in width, is covered with bungalows and

little

native properties, and is so full of coconuts and palms that all effect

of the

mountains is lost. Though it was only the month of September at the

time of our

visit it was very hot and airless, making all mental and physical

exertion an

effort. I went one morning for a walk at 6.30 in the hope of better

things, but

even then it felt as if Nature had forgotten to open her windows. The

wild charm

of romance which greeted the early voyagers and which must have

assuaged the

struggle of the first missionaries is now no more. Papeete is

civilised: it is

a port for the mail steamers between America and New Zealand. It is

under

French rule, but a large proportion of business is in the hands of the

British

and also of the Chinese. We lived

at the hotel, as Mana had to go on

the slip, and had an interesting fellow guest in an American geologist.

He was

travelling in the Pacific with the object of proving that it had never

been a

continent, but that the islands were sporadic volcanic upheavals from

the ocean

bed. He had found himself involved in the everlasting quarrel between

geologists and biologists, who each want the world constructed to prove

their

own theories. In this case a biologist wished for continuity of land to

account

for the presence of the same snail in islands far removed. Our friend

had

contended that the molluscs might have travelled on drift-wood, but was

told in

reply that salt water did not “suit their constitution." He had then

argued that they could easily have gone with the food in native canoes.

"Anyhow," he concluded, with a delightful Yankee drawl, “to have the

floor of the ocean raised up fifteen thousand feet, for his snails to

crawl

over, is just too much." S. was

presented by the Consul to the French Governor, and I called, according

to

instructions, to pay my respects to his wife, who proved to be both

young and

charming. She was good enough subsequently to send an invitation to a

tea-party, which differed interestingly from similar functions at home.

It took

place in a large room where twenty chairs, covered with brocade, were

arranged

in a circle which was broken only by a settee. On this sat the hostess,

and by

her side, either as the greatest stranger, or as having taken the

precaution to

be an early arrival, the Stewardess of the Mana.

One by one the chairs filled up, and each fresh arrival, after greeting

her

entertainer, went round and shook hands with every one already there.

The

hostess retained her seat, from which she conversed across to various

points of

the circle. No one moved except that when a delightful tea came in, it

was

handed round by the young girls; no servant appeared — they are almost

impossible to get. The Governor earned our particular gratitude by his

kindness

in sending daily a copy of the war bulletin, which arrived by wireless

from

Honolulu and New Zealand; though the installation was not at the time

sufficiently advanced to be capable of sending out messages. The

Germans were interned in the bay on what was known as Quarantine

Island, and

were employed to do a certain amount of leisurely work on the roads, at

a

comparatively high rate of pay; at the same time the French subjects,

native

and half-caste, had been called up for much harder military service and

received the standard remuneration, which was much lower. It was

commonly

reported that the latter had sent in a petition humbly begging that

they might

be considered as German prisoners. During our

time on the island the anniversary occurred of the visit of Von Spec's

fleet on

their way to Easter Island, and the trees were adorned with official

notices

proclaiming a public holiday in memory of the French victory. What

happened on

that occasion is not precisely clear, and each person gives a different

account. It seems, however, that as the cruisers Scharnhorst

and Gneisenau

appeared without any proper announcement, the shore batteries fired

across

their bows to stop them. The Germans replied, and some houses in the

town were

set on fire. The French gun-boat Zelée

was sunk in the harbour, also a German ship which had been taken as a

prize.

The custodian of the coal supply set it on fire to prevent it from

falling into

the enemy's hands; this action was subsequently justified, as it

transpired

that the Germans had given out that they were going to Papeete in order

to

obtain coal. After a certain number of shots had passed in both

directions, the

enemy went on their way. We had

particular pleasure in making the acquaintance of the late Queen, widow

of

Pomare V., an able and cultured lady, who lives in a villa in Papeete,

and

calls herself simply "Madame Marau Taaroa." She was kind enough to

lend us a valuable book written by her mother, Arii Taimai, which tells

the

history of the island as related by family traditions and combines with

this

account the information given by the early voyagers. Her charming

daughter.

Princess Takau Pomare, who had been educated in Paris, placed us under

a great

obligation by constituting herself our cicerone. She took us to see the

monument on Venus Point, erected to mark the spot where Cook observed

the

transit of Venus; and also the Pomare mausoleum. Miss Gordon Gumming

records

that it was the ancient habit at Tahiti for the dead to be placed in a

house,

watched till only dust and ashes remained, and then buried securely in

the

mountain to guard against possible desecration; this custom, she

states, still

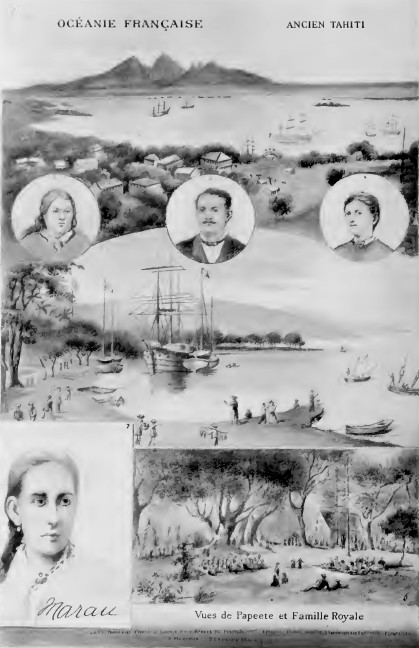

survived in her day in the case of departed royalty.  FIG. 130. — A TAHITIAN PICTURE POST-CARD. Used as menu card at a luncheon given by the ex-Queen Marau. 1. Papeete, capital of

Tahiti, with the

Island of Moorea in the distance. From a sketch by Miss Gordon Gumming.

2.

Queen Pomare IV. 3. King Pomarc V. 4.Titaua, sister of Queen Marau. 3.

The

harbour, "of Papeete. 6. Himène (or chorus) singers: performance in

honour

of Accession of Pomarc V and Marau. From a sketch by Miss Gordon

Cumming, 1877.

7. Queen Marau, with autograph. We had

also a delightful motor drive with the Princess to some family property

on the

south side of the island, lunching at a small hotel which. was nothing

if not

up-to-date, being dignified with the name of the Tipperary Hotel. The

proprietor, a Frenchman, advertised it by stating that while it was a

"long,

long way to Tipperary," it was only a short way to his establishment.

He

had adorned the walls of the dining-room with large frescoes of the

flags of

the Allies, leaving, as he explained, “plenty of room for Holland,

Greece, and

America." The marae

of Tahiti have vanished, but on the way back we stopped to see all that

remains

of a once famous pile. Nothing now exists but a mass of overgrown coral

stones,

converted into a lime kiln. Fortunately Cook and his companion Banks

both

visited Mahaiatea in its glory and have left us descriptions, and we

have also

a drawing of it. It is obvious that these structures in no way

resembled the

ahu of Easter Island. Mahaiatea was a pyramid of oblong form with a

base 267

ft. by 71 ft.; it was composed of squared coral stones and blue

pebbles, and

consisted of eleven steps each some 4 ft. in height. It impressed Banks

as

"a most enormous pile, its size and workmanship almost surpassing

belief."3

The pyramid formed one side of a court or square, the whole being

walled in and

paved with flat stones. Marae, as

Arii Taimai explains, were sacred to some god; but the god was only a

secondary

affair; a man's whole social position depended on his having a stone to

sit on

within his marae enclosure. Cook was asked for the name of his marae,

as it was

not supposed possible that a chief could be without one, and took

refuge in

giving the name of his London parish. Stepney. Princess

Takau kindly acted as interpreter when we went to look up the Easter

Islanders

who came here to work on the Brander plantation and who still form a

little

colony. One of our main objects in visiting Tahiti had been to inspect

the

tablets and Easter Island collection of Bishop Jaussen who died in

1892. In

this we met with disappointment; the present authorities, whom we saw

more than

once, took no interest at all in the subject, and said that on Bishop

Jaussen's

death, the Brothers had sent the articles home as curios to their

friends in

Europe. They gave us an address in Lou vain, which it has not of course

up to

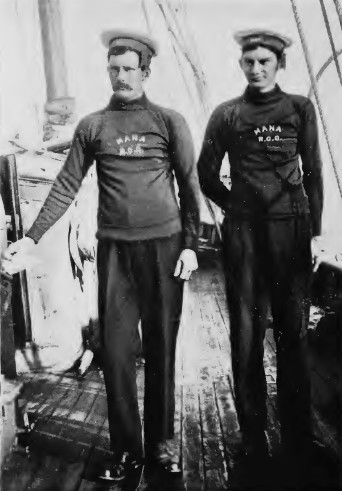

the present been possible to follow up.  FIG. 131. — MARAE MAHAIT (From A Missionary Voyage in the Ship Duff, 1796-98.)  FIG. 132. — CHARLES AND EDWIN YOUNG. The great-great-grandsons of Midshipman Young, the only commissioned officer among the mutineers of the Bounty who took refuge on Pitcairn Island, 1790 Our crew

underwent some alterations at Tahiti. The post of engineer had been

filled by a

Chilean, and one deck hand had already gone home as a reservist; two

more now

desired to return direct to "serve their country,” one of these was my

friend Bailey, the cook. As he had had no opportunity of spending his

wages, he

was, on being paid off, quite a millionaire. He invested in a number of

white

washing suits and took up his residence at our hotel. I was presented

with his

photograph clad in the new raiment. An officer travelling to England

from New

Zealand was kind enough to undertake to give him some care on the

journey, and managed

to get him safely home, though most of his fortune had disappeared en route. He took service as a ship's

cook, and we saw his name subsequently, with most sincere regret, in a

list of

"missing." Bailey's

place was taken by an American, who had formed part of the crew which

had been

discharged from a ship which they had brought to Tahiti from

California. He

declined to come onboard till just before we sailed, as he was engaged

for a

prize-fight with a noted coloured champion; the prospective fight

excited a

good deal of local interest, but ended lamentably in the white man

being

knocked out at the first blow. As we were still short-handed, we

arranged with

our two Pitcairn Islanders to come on with us to England; Charles Young

was

signed on as deck-hand, and Edwin, who was of less strong physique, as

steward.

They both gave every satisfaction, and Edwin, though he had of course

to be

taught his duties, was the best steward we ever had. We had

considerable conversation with our Consul, Mr. Richards, on the subject

of

Pitcairn, in which he has always taken great interest, doing all that

he could

for the Islanders. He had been anxious if possible to make a stay there

of some

duration, feeling, no doubt rightly, that the only way to solve its

difficulties was for someone to dwell there long enough to see the

situation,

not as a visitor, but as a resident. Circumstances had not, so far,

rendered

this feasible, but it is to be hoped it may still be accomplished. It was

impossible to make a direct passage from Tahiti to Panama, as the Trade

Wind

would have been dead against us, we had, therefore, to turn its flank

by going

as far north as the Sandwich Group, or, to give them their American

name, the

Hawaiian Islands. We passed within sight of one or two of the Paumotu

group,

which was our first introduction to coral atolls; but I do not think we

saw a

ship during the whole voyage. It was a

long run, as we met with calms in the Doldrums, and were without the

use of the

motor, which stood in need of some simple repairs, that could not be

done in

Tahiti, Being becalmed is certainly unpleasant, there is no air,

everything

hangs loose, rattles and bangs, and cheerful calculations are made as

to how

much damage per hour is being done to the gear; but on the whole the

patience

of seamen is marvellous. Occupation happily was provided in the

stupendous

quantity of arrears of newspapers. We read them most diligently, but it

is

hardly fair to journalists to deal with their output a year after it is

written, the mistakes and false prophecies of even the most sober

papers become

painfully obvious. We became acquainted, for example, at one and the

same time

with the birth and death of the "Russian steam-roller" theory, and

other similar figments. My diary is diversified by such items of

domestic

interest as "showed Edwin how to look after the brass." "S.

taught Edwin to clean silver." The group is composed of

eight inhabited

islands which stretch in a line from north-west to south-east. Hawaii,

the most

southerly, is the largest, and now gives its name to the whole, but the

principal modem town, Honolulu, is on the more northerly island of

Oahu, The

islands were known to the early Spanish voyagers, but their connection

with the

civilised world really dates from their rediscovery by Cook. He called

them

after Lord Sandwich, who was at that time First Lord of the Admiralty.

The

great navigator was murdered on Hawaii in 1779. Vancouver touched there

more

than once, and obtained the consent of the natives to a British

Protectorate,

which he proclaimed on Hawaii in 1794; the action was however ignored

by the

Home Government. "At this time a powerful

chief of

Hawaii, Kamehameha I, rose to pre-eminence. He captured the island of

Oahu in

1795, and consolidated the group under one government. Contact with the

outside

world gradually undermined the native beliefs and the old ceremonial

taboos

became wearisome. After the death of Kamehameha they were overthrown by

his

son, in 1819, though not without armed resistance from the more

orthodox

section. The islands were for a short time "a nation without a

religion";

but Christianity was introduced almost immediately by American

missionaries. The group was nominally

independent till the

time of Queen Lihuokalani, who succeeded in 1891. Her rule roused much

resentment among the foreign residents, and during a period of

unsettlement she

was imprisoned in her palace for nine months. An appeal was made to the

United

States, and the islands were formally annexed by that power in 1898. Oahu. — After a five-weeks' voyage, which

included an abortive attempt to call at the island of Hawaii, we

reached

Honolulu, in the island of Oahu, on November 11th, 1915. From the

isolation of Easter we had come to the comparatively busy life of

Tahiti, and

now at Honolulu we felt once more in touch with the great world. It is

a

cheerful and up-to-date city in beautiful surroundings. Seen from the

harbour

it is not unlike Papeete, but the town is bigger, and the mountains

more

distant. The roads of the suburbs are frequently bordered by large

areas of mown

grass, which form part of the gardens of the adjacent villas. It is

considered

a duty to erect no wall or paling, and the custom, while it deprives

the

residences of privacy, greatly enhances the charm of the highway. The

practice

is encouraged by a public-spirited society, interested in the beauty of

the

place. The aquarium contains fish of most gorgeous colouring, and it is

well

worth while to explore a coral reef on the eastern shore in a

glass-bottomed

boat. In

addition to the original population, the place swarms with Japanese,

and the

Americans seem little more than a ruling caste. The natives are

reported to be

entirely sophisticated, and quite competent to invent folk-tales or

anything

else to order. The Bishop Museum has an interesting collection of

relics and

models of the old civilisation, and we are much indebted to the

Director, Dr.

Brigham, for his kindness in exhibiting them to us. The principal

treasures are

the wonderful feather cloaks and helmets of the old chiefs. Fifty men

were

employed for a hundred years in collecting the yellow feathers from

which one

cloak is made. The birds, which produce only a few feathers each of the

desired

colour, were caught on branches smeared with gum. There is

also in the museum an excellent model of one "heiau," or temple; it

is shown as a rectangular enclosure containing various sacred

erections. This

form of heiau has no resemblance either to the marae of Tahiti or the

ahu of

Easter Island; and the art of building never seems to have approached

the

excellence reached in the latter. Mr. Gordon, the British Consul, gave

us much

pleasure by taking us in his motor, accompanied by Dr. Brigham, to see

the

remains of one of these temples on the eastern side of the island.

Little now

exists save a rough enclosing wall. It is a matter of surprise that,

under so

enlightened a government as the American, more pains are not taken to

preserve

the archaeological monuments throughout the islands, which are fast

disappearing. Much care is bestowed on attracting visitors, and it

would have

seemed, even from the financial point of view, that the protection of

these

objects of interest would have been eminently worth while. We also

visited the famous Pali, the site of a great battle at the time of the

conquest

of the island by Kamehameha, chief of Hawaii. A range of mountains runs

along

the eastern side of the island. The visitor, approaching from the west,

rises

gradually till he reaches the summit, and is then confronted by a sheer

drop of

many hundreds of feet down to the coast below. The cliff

extends for many miles, and the views over land and sea are most

striking.

During the invasion, the Hawaiian army pursued the natives up the

slope, and

drove them headlong over the Pali, or precipice. Kamehameha is the

national

hero; when a statue was erected in Honolulu, to commemorate the

centenary of

the discovery of the island by Cook, it was dedicated, not to the

navigator,

but to the Hawaiian chief. We were

accorded an interview with the ex-queen Liliuokalani. It was a

distinctly

formal occasion. We were shown into a waiting-room till some previous

arrivals

had finished their audience, and were then ceremoniously introduced to

royalty.

The room was furnished after European fashion, but was adorned with

feather

ornaments. The old lady, who had a tattoo mark on her cheek, sat with

quiet

dignity in an arm-chair. She was obviously frail, and though she spoke

occasionally in good English, her secretary did most of the

conversation. She

told us that her brother had caused certain native legends and songs to

be

written down, and she herself, during her imprisonment in 1895, had

translated

into English an Hawaiian account of the creation of the world. The

secretary

presented us with a copy of this book. We did not gather that either of

them

had ever heard of Easter Island. After a short time we took our leave,

curtseying again and backing out as we had seen done by our

predecessors. It

may be remembered that Liliuokalani visited England at the time of

Queen

Victoria's Jubilee. Since our return we have seen the announcement of

her

death; so closes the list of the Hawaiian sovereigns. Being in

harbour brought the not unknown domestic excitements. The pugilistic

American

cook, who had been quite satisfactory on the voyage, proved to be one

of those

who cannot be in port without going "on the bust." He was rescued

once, but he shortly afterwards asked for shore leave at lo o'clock in

the

morning. This was naturally declined; he then said he wanted to have a

tooth

out. S. assured him he was quite capable of officiating. Finding he

could get

neither leave, money, nor a boat, he sprang overboard, and swam ashore

in his

clothes. His place was taken by a Japanese cook from Honolulu. Hawaii. — When the repairs to the engine had

been

accomplished, we sent the yacht ahead to San Francisco, and ourselves

made a

trip by steamer from the island of Oahu to that of Hawaii. Between the

two lies

the island of Molokai, on which is the leper settlement, connected with

Father

Damien's heroic work and death. We did not see the settlement itself,

but from

its photographs it seems an attractive collection of small houses, in

the midst

of wonderfully beautiful scenery. The

principal sight on Hawaii is the active crater of Kilauea. Instead of

the long

ride described by Lady Brassey, visitors, landing at the port of Hilo,

are now

conveyed in motors to a comfortable hotel, on the edge of the crater.

We made a

detour on the way to see a genuine native settlement, where the

standard of

living proved to be much the same as on Easter. The crater itself is a

subsidiary one on the side of the great mountain, Mauna Loa; it is

4,000 feet

above sea-level, and has a circuit of nearly eight miles. The greater

part of

the crater is extinct, and its hardened lava can easily be walked over,

but one

portion is still active, and forms a boiling lake about a thousand feet

across.

No photograph gives any idea of the impressiveness of the scene,

particularly

after dark. The floor of the pit is paved with dark but iridescent

lava, across

which run irregular and ever-varying cracks of glowing gold. First one

of these

cracks, and then another, bubbles out into a roaring fire, the heat

melts the

adjacent lava, causing great dark masses to break off and slip into the

furnace, where they are devoured by the flames. It is a fascinating

spectacle

which could be watched for hours. The floor of the pit rises and sinks;

when we

were there it was some hundreds of feet below the spectator. Kilauea

was considered in olden times to be the special abode of Pele, the

goddess of

fire; but after the advent of the missionaries, her power was formally

defied

by Kapiolani, the daughter of a chief who ate the berries consecrated

to the

deity on the brink of the pit. More than fifty years later, however, in

1880, there

was so great an eruption of lava on the other side of Mauna Loa that

native

royalty had to beseech Pele to stifle her anger and save the people; a

prayer

which was, it is said, immediately effective.  FIG. 133. — HEIAU PUUKOHOLA, HAWAII. We

decided not to return to Hilo, but to see something more of the island,

and

catch the steamer at Kawaihae on the western side. We left the hotel at

8 a.m.

and motored over a hundred miles, first passing through grass lands and

cattle

ranches, and then through sugar plantations. The way was diversified by

extraordinary flows of lava, through which the road had been cleared:

they

extended for miles like a great sea; one of the streams was as recent

as 1907.

The last stage of the drive was through forest growth and coffee

plantations.

We spent the night at a small hotel, kept by a lady. An interesting

fellow-guest was a government entymologist, who was combating a

parasite which

was injuring the coffee; to this end he had introduced an enemy beast

of the

same nature brought from Nigeria, which was successfully devouring its

natural

foe. Below the

hotel was the Bay of Kealekakua, which was the scene of the last great

drama in

the life of Cook. On its shore are the remains of the building where he

was

treated as the incarnation of the god Loro. It is now only a mass of

stones,

but is said to have been a truncated pyramid, which is an old form of

heiau. On

the top of this temple Cook was robed in red tapa, offered a hog, and

otherwise

worshipped. The conduct of the white men, however, was such that they

soon lost

the respect of the natives. An affray occurred over the stealing of one

of the

ship's boats, and Cook was stabbed in the back by one of the iron

daggers which

he had himself given in barter. An obelisk has been erected to his

memory. On the opposite

side of the bay is a "puuhonua," or place of refuge, by name

Honaunau. It corresponded with the cities of refuge in the Old

Testament. “Hither,"

says Ellis, “the manslayer, the man who had broken a tabu, . . . the

thief and

even the murderer, fled from his incensed pursuer and was secure."4

It covered seven acres, and was enclosed on the landward side by a

massive wall

12 ft. high and 15 ft. thick. In the

afternoon we motored on to Waimea by a cornice road, which was bumpy

beyond

description. The hotel consisted of a few rooms behind the principal

store. The

next morning, on the way to the steamer, we inspected two heiau, a

small one at

the foot of a hill, and a large and striking one on its summit known as

Puukohola. Tradition says that the hero Kaméhaméha set out to rebuild

the

former in order to secure success in war, but was told that, if he

wished to be

victorious, he must erect a temple instead on the higher altitude. The

temple, which adapts itself to the ground, rises on the seaward side by

a

series of great terraces and culminates on the summit in a levelled

area paved

with stones. On the landward side the building is enclosed by a great

wall, on

which stood innumerable wooden idols. It was entered by a narrow

passage

between high walls. On the area at the top were various sacred

buildings,

including a wicker tower, out of which the priest spoke; an altar, and

certain

houses, in one of which the king resided during periods of taboo.

Whilst the

temple was being built, even the great chiefs assisted in carrying

stones, and

the day it was completed (1791 c.) eleven men were sacrificed on the

altar.5

It is one of the latest, as it is one of the finest of the heiau. From

the

walls are magnificent views of the two great mountains of Hawaii, Mauna

Kea and

Mauna Loa, both over 13,000 ft. It was

interesting to recognise in the Hawaiian language not a few words

similar to

those which we had learnt on Easter Island. In Polynesian the letters K

and T

are practically interchangeable. Thus Mauna Kea, meaning Mount White,

from its

usual covering of snow, is equivalent to Maunga Tea-tea, the hill of

white ash

in Easter. The same is true of the letters L and R. Mauna Loa is Mount

Long

just as Hanga Roa is Bay Long. The identification of these last letters

is not

confined to Polynesia. We made one of the Akikuyu in East Africa repeat

the

same word over and over again, to see if it had the sound of L or R; he

used

first one and then the other without any discrimination. The names in

Hawaii

are said to exist in their present form simply according to the manner

in which

they have been crystallised in writing. We duly

caught our steamer to Honolulu, and changed there into the boat for San

Francisco.

Cortez, Governor of Mexico,

was under the

impression that America was in close proximity to Asia. Hearing of the

success

of Magellan in discovering a southern route to the westward, he sent an

expedition to the north, with the object of finding a road to India in

that

direction. The members of this party, which was commanded by Cabrillo,

were the

first Europeans to discover California (1542). The native Indian

population at

that time is supposed to have been about seven hundred thousand in

number. For over two hundred years

Spain took but

little interest in the new country; but in 1769 she began to be alarmed

lest

the Russians should descend on it from the north, and its occupation

was

ordered from Mexico. In this movement, not only was the secular power

represented, but Catholic missions played an important part. The

Franciscan

order was first in the field; and the mission station, which gave its

name to

the Bay of San Francisco, was dedicated in 1776. Later the Dominican

order also

founded religious establishments. These institutions were finally

secularised

in 1836, but Californians justly regard the remains as the most

romantic as

well as historic objects in the country. A wave of immigrants from

the United States

began to arrive about 1841; war broke out with the parent country of

Mexico in

1846; and in 1848 California was formally transferred to the States.

The same

year, 1848, the first discovery of gold caused an enormous inrush of

population. The journey was no easy one; for twenty years the would-be

immigrant from the east had to choose between the dangerous expedition

overland, the unhealthy condition of the Panama route, or a voyage

round the

Horn. The Pacific railway was at last completed in 1869. The most dramatic event of

recent years has

been the earthquake of 1906, which was followed by a great fire, when

for three

days the city was a mass of flames. We

arrived at San Francisco on December 14th, 1915. The bay recalls in

some degree

that of Rio de Janeiro, the ocean has in the same way penetrated

through a

narrow channel into a low district surrounded by mountains and formed

it into

an inland sea. There, however, the resemblance stops. The Bay of San

Francisco

runs, for its major portion, parallel to the sea, and thus forms a

peninsula on

either side of the entrance, the well-known Golden Gate. The tract on

the

southern side is sufficiently level to allow of the site of a town. The

main

frontage of the city is on the bay, but it extends to the seaward side.

The

population has also spread across the bay, and the suburbs have

attained to the

magnitude of towns. The large ferry boats which ply across the water

are marked

features of San Francisco life. There was

nothing in the present fine city to recall the fact that ten years

before it

had been laid low by the great fire, but any building dating back more

than a

score of years is treated with respectful interest. A professional

guide, who

escorts tourists in a motor char-à-bancs, solemnly stated that such and

such

houses were "in the style of thirty-five years ago," or that a church

was "one hundred years old, but still used for service." It is

not, however, in such matters that the youth of California most strikes

a

visitor from an older country. Its inhabitants appear to him to

resemble

children who have discovered a new playground, and who are busily

occupied in

seeing what each can find there. They seem, with notable exceptions, to

have

little time to spare for those deeper studies and questionings which

form part

of life in lands where the earlier stage has long been passed. There

are, no

doubt, in the gay crowd many profound thinkers, numbers with

unsatisfied

longings and broken hearts, but they are not obvious in the general

cheerful

absorption as to how much everything costs and everybody is worth. The

stranger

also, however much theoretically prepared, experiences a shock in

finding how

little a population formed from manifold races has as yet amalgamated;

the

owner of a shop, for instance, may not be able to speak even

intelligibly the

language of the country of his adoption. Depressing accounts were given

of the

type of man who thought it worth while to take up political life, and

the

consequent short-sightedness of some of the legislative measures. We

were

frankly told that we were much better off with our British monarchy,

and once

an American-born citizen was even heard to regret the War of

Independence. With

regard to the Great War we were told that at that time ninety-five per

cent. of

the population of San Francisco were pro-Ally, though a few professors

still

looked to Germany as the home of culture. Conversation on the subject

was

definitely discouraged, and one man, who spoke to us for a few minutes

concerning the struggle, ended by saying, “I have not talked so much

about the

war for months." It was naturally impossible to appreciate at so great

a

distance the feeling which pervaded Europe. A high authority, whom we

consulted

as to where we could see some Indian life, recommended us to go to a

certain

German mission and "ask for hospitality from the Fathers"; that we

should prefer not to do so he obviously thought most narrow-minded.

Affairs in

Mexico where some Americans had just been killed by the insurgents were

much

more interesting. Even Japan and Australia appeared more closely

connected with

everyday life, and not only seemed nearer than Europe, but than the

Eastern

States themselves. So was brought home the truth of the saying that

"oceans unite, not divide"; also that the Pacific and its seaboard

are really an entity, however much the atlas may prefer to give a

contrary

impression. Later it was impossible to think without deep sympathy of

this

young community plunged whole-heartedly with all its fresh ardour and

keen

intelligence into the solemn crucible of war. We

received welcome help and hospitality from Mr. Ross, our

Consul-General, Mr.

Barneson, the Commodore of the leading yacht club, and other kind

friends. Mr.

Adamson, of Messrs. Balfour & Guthrie, a firm allied to our Chilean

friends

Williamson & Balfour, came opportunely to our assistance when the

censor

felt that a cabled draft from England was too dangerous a document to

pass

without many days of consideration. We were

naturally much interested in making the acquaintance of our

anthropological

confreres of the University of California, Dr. Waterman and Mr.

Gifford, and in

hearing of their important work among the surviving Indians. A luncheon

party

at the University buildings at Berkeley, one of the suburbs on the

other side

of the bay, was both pleasant and enlarging to the mind. It is a mixed

university, with some five or six thousand students; situated in

beautiful

surroundings and with an enviable library. One of the guests at

luncheon was a

German professor, who was at work in New Guinea when the war broke out;

the

account runs that the British troops, hearing there was an expedition

in the

mountains, went there expecting to encounter an armed force. He was

detained in

California, unable to get home.  FIG. 134 — SAN FRANCISCO. From Mount Tamalpais, looking across the Golden Gate. Christmas,

the third since we left England, we spent in an hotel on the top of

Mount

Tamalpais, which is on the other side of the Golden Gate, and directly

opposite

to San Francisco. It is reached by a mountain railway, and gives most

beautiful

panoramic views of ocean, city, and bay. The management have hit on the

ingenious plan of pointing out special sights, by placing tubes on the

walks

round the mountain, at the level of the eye, oriented on particular

places and

labelled accordingly. At night the scene is marvellous; the city

appears as a

blaze of illumination, and lights in every direction are reflected in

the still

water of the Bay. While on Mount Tamalpais we received a telephone

message to

say that Mana was coming through the

Gate. She had taken two days less to do the distance from Honolulu than

a

four-masted barque which left about the same time. We could not get

down before

her arrival, so left Mr. Gillam to grapple with the usual officials;

and not

least with the reporters, seventeen of whom, he declared, came on

board. We had

had our share of the representatives of the press, but any temptation

to

self-complacency would have been quenched by the knowledge that real

success in

newspaper paragraphs had already been achieved by the American cook who

left in

so summary a fashion at Honolulu. He had turned up from Hawaii and

given out

that he had been obliged to quit the yacht because he "could not stand

a

spook ship with skulls on board." Except by one Christian Science

reporter, scientific research was considered dull, but this aspect of

our work

gave a hope of copy; and we received a request, from more than one

agency, that

we would pose for moving pictures on the deck of the yacht exhibiting

the said

skulls to one another. The

Pitcairn Islanders almost rivalled the cook as objects of popular

interest; as

the men had nothing to gain from notoriety, we fixed a modest sum to be

given

them by each reporter whom they saw; as might perhaps have been

foreseen, an

interview then appeared without any such unnecessary preliminary as a

previous

conversation. Charles and Edwin told us that the life of a great city

surpassed

even their expectations, but it must be confessed that their most

enthusiastic

admiration was aroused by Charlie Chaplin as he appeared at the picture

palaces. The

Exhibition was just over, and Mana

was moored alongside the now deserted buildings, which even in their

then

condition were well worth seeing. We had understood that there would be

no

difficulty about our new cook, as he was not Chinese, and came from an

American

dependency, but he was forbidden by the authorities to go on shore.

This ruling

we had, of course, no means of enforcing; and we found also that we

were liable

to a fine of over £100 if we could not produce him when we sailed. It

was not

encouraging to be told that there were plenty of people who would

entice him

away for a share in the fine, and it was a relief when Mana

at length sailed having all her crew safely on board. It had

been arranged that I was to return home overland, in order to avoid the

long

hot voyage on the yacht, and to put in hand preliminary arrangements

there. I

left on January 16th, taking the more southerly route across the

continent. A

night was spent at Santa Barbara, to see the mission buildings which

are in the

hands of one of the two remaining San Franciscan communities. The

Brother who

acted as guide, and who was of Hungarian Polish descent, said that it

had been

instrumental in converting between 4,000 and 5,000 Indians. From Santa

Barbara

the route runs to Los Angeles, which forms a winter resort for various

Central

American millionaires. A detour was made to the Grand Canyon, which is

perhaps

more impressive than beautiful, and so to Washington. A happy time was

spent in

seeing the city, and being shown over the National Museum by Dr. Walter

Hough.

The objects brought from Easter by the Mohican

naturally proved of the greatest interest. At New York the beautiful

Natural

History Museum excited admiration, and gratitude is owed for the

kindness of Dr.

Lowie. At that time we were considering the question whether, owing to

war

conditions, to lay up or sell Mana in

New York. Nothing could have been kinder than the assistance given in

my search

for information by more friends than I can mention. It was finally, as

will be

seen, decided to bring her home. The crossing of the Atlantic in an

American

vessel was uneventful, and on Sunday, February 6th, 1916, I found

myself, with

an indescribable thrill, at home once more in the strange new England

of time

of war; which was yet the dear familiar England for which her sons have

found

it worth while to fight and if need be to die. 1 Another

daughter was the wife of Mr. Brander, the connection of whose firm with

Easter

Island has already been seen. 2 My

budget contained, with over twenty letters from my Mother, the news

that she

had died suddenly the preceding April; and that the old home no longer

existed.

The tidings were no surprise. Iliad had the strongest convict-on,

dating from

about one month after her death, that she v/as no longer here. The

realisation

came at first with a sense of shock, which was noted in my journal and

written

to friends in England; afterwards it continued with a quiet persistence

which

amounted to practical certainty. 3 Journal of Sir Joseph Banks,

p. 102. 4 Polynesian Researches, vol.

iv. p. 167. 5 Thrum. Hawaiian Annual, 1908. |