| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

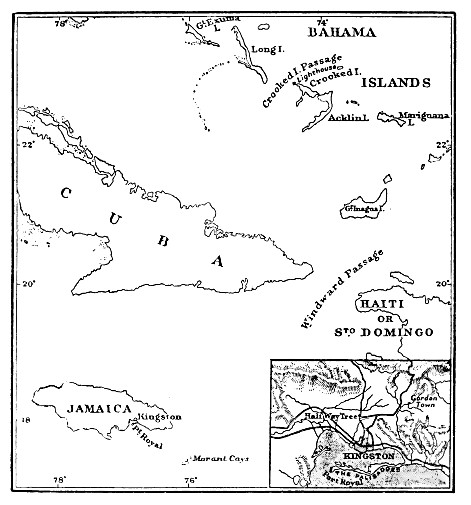

CHAPTER XXIV JAMAICA TO SOUTHAMPTON Jamaica, and the Bahamas Bermudas ^Azores Preparing for Submarines Southampton once more, JAMAICA Jamaica was discovered by

Columbus, and

belonged to Spain till 1655, when it was captured by an expedition sent

out by

Oliver Cromwell. The Island, from its

proximity to the Spanish

Possessions, was a godsend to the Buccaneers. Port Royal, which, as its

name

shows, was founded after the Restoration, was full of riches, often

ill-gotten:

"always like a Continental mart or fair." In 1692 it was overwhelmed

by an earthquake, and again laid low by fire in 1703. Kingston, originally begun

as a settlement of

refugees from Port Royal after the earthquake, gradually grew in

importance,

and finally became the capital of the island. During the wars which

followed the French

Revolution, Jamaica was of importance as the great centre of British

interests

in the Western Caribbean. We now

headed for Jamaica; Kingston, its capital, lies towards the eastern

extremity

of its southern coast. The town is placed on fiat land which gradually

rises

into dwarf hills. It is built parallel to, and abutting on to its

water-front.

Right and left of the city, when viewed from the sea, extends low

country,

whilst behind it, and to the east, rises in the distance a lofty range

of

mountains. From the open sea, the town and flat country is divided by a

natural

breakwater that maintains the general trend of the coast. By this

breakwater is

formed a lagoon that runs East and West, parallel to the coast, for a

distance

of some six miles, with an average breadth of about one mile, and has

practically no arms or branches. This lagoon is the harbour of Kingston

and a

fine one, but it lacks the element of picturesqueness, nor is it a

comfortable

one for small craft. The strong easterly wind, known as "The

Undertaker," that daily arises and increases in strength with the sun,

sweeps down its length and knocks up a nasty sea. It is difficult to

obtain

shelter, even for a dinghy, when landing at Kingston. But we

are anticipating. We ran down the coast, close in, and at 9.30 a.m.,

Friday,

April the 7th, 1916, we reached the western end of the natural

breakwater

between which and the mainland is the passage into the lagoon. Here the

Port

Doctor came on board, and as he went through our bills of health we

mutually

discovered that we were old hospital friends, though we had never heard

of each

other for twenty years. We entered

the harbour, and brought up in 15 fms., abreast of the wharf of the old

naval

dockyard of Port Royal, and distant from it about a cable's length.

Port Royal

is situated on the inner aspect of the bulbous-headed western extremity

of the

natural breakwater. The land surface is very limited in extent and is

entirely

taken up with the old fort, the old dockyard, and old naval and

military

quarters. All but a few poor closely packed houses is in the occupation

of

Government. The width of the breakwater to the eastward soon becomes

small;

open beach on seaward side, mangroves extending into the lagoon on the

other;

and between the two sand and scrub. This part is the well-known

Palisadoes, the

home of land-crabs and dead men, and the scene of many a duel. Port

Royal is

now deserted; no shipping or living workshops; everything is hushed,

but the

place is not neglected. Nelson might have left it but yesterday; the

dockyard,

with its fittings, stores, and quays, reminded one of that other quaint

little

marine gem, the old naval dockyard of English Harbour in the island of

Antigua.

When the place hummed with life, The

Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor, by Falconer, was the text book to

work

by, and its social life is vividly and accurately given us by Marryat

in one of

his novels. As in the

dusk, all alone, we passed down the silent corridors, and approached

the old

mess-room, we somehow listened for, and expected at any moment to hear,

through

some opening door, the reckless toast of "A bloody war, and a sickly

season,"

the chink of glasses, and the crash of the chorus "Yellow Jack! Yellow

Jack! And Jack, thus bidden, used to come, and link his arm in that of

some

fine young fellow, and together the two would saunter away "to the home

of

a friend of his in the Palisadoes." Little time for packing up allowed!

Many and many a man, in the prime of life and feeling quite well, has

dined at

mess one night in snowy uniform: the next night in a white uniform of a

different cut as the guest of Jack and Death. These two kept open house

in

those days. The R.E.

Officer in charge was most kind and hospitable; he took us over the old

fort,

pointing out, amongst much else. Nelson's former quarters and the

adjoining

length of parapet overlooking the harbour entrance, now known as

Nelson's Walk.

Our host informed us that, fishing from the wharves, he got splendid

sport. From Port

Royal to Kingston is about four miles by the boat channel. Passes

through the

coral banks have been blasted where requisite and the channel beaconed.

A least

depth of 4½ ft. is thus obtained, and a

direct course. Our little motor lifeboat carried us backwards and

forwards most

excellently on various voyages made to attend to our business at

Kingston. The

way in which she bucked at speed over the short steep seas reminded one

of

larking over hurdles on a pony. The work

in hand was to get our clearance inwards, to get rid of our

food-destroyer from

Panama, and to find in his place a live ship's cook, to report

particulars of

the Morant's Cays upheaval, and finally the usual catering, and bill of

health,

and clearance outwards. The Chief of the Customs was good enough to

interest

himself in Mana's welfare, so that

all these matters were dealt with in due sequence, and with the least

possible

trouble to us. A coloured cook was procured from an hotel at £16 a

month, with,

as it proved, but little justification on the ground of ability for

drawing

such a rate of pay; still, his professional enormities were associated

with so

many humorous incidents, and as he appeared at least to mean well, we

resigned

ourselves to the inevitable, and prayed that we might survive his

ministrations. About

noon on Sunday, April 9, 1916, we weighed and motored out from Port

Royal,

unplagued by pilots, and dipping our ensign to the Port Doctor and his

wife, in

acknowledgment of adieux waved from their garden. Clear of everything,

the

engines were stopped and Mana, bound

to "the stormy Bermuthies," proceeded to argue the point with a head

wind as to whether she should, or should not, go to windward. By steady

hammering she gradually got under the western end of the Island of San

Domingo,

and then through the celebrated Windward Passage. We had now to

threadle our

way betwixt the numerous islets that constitute the Bahama group, and

it was

quite delightful and interesting; brilliant sunshine, cool moderate

breezes,

land every few hours, but reliable charts. This was yachting; we had

met a good

deal of what bore little semblance to it, so we appreciated our present

luck

all the more. The morning

of the 19th of April 1916 saw us beating up under the lee of Acklin

Island and

of Crooked Island; a fresh N.E. breeze swept in puffs across the long,

narrow,

fiat land. An open native boat, with jib-headed mainsail as usual, was

seen

heading across our course when we were close in, so we gave her a wave,

and, as

we came into the wind, she rounded-to under our stern, dousing her

sail,

unshipping her mast and shooting up alongside our quarter. We dropped

into her;

a couple of empty sacks were pitched in, and she was clear of the ship

before

she had lost her way. The mast is stepped, the sail hoisted, and she is

off

again with her gunnel steadily kept awash. We now for the first time

spoke. The

two coloured men, her crew, were most obliging; they would make for the

most

convenient landing and then they would accompany us catering. Everything

went off excellently; we made a tour to different cottages and gardens,

collecting whatever was available, particularly grape-fruit, oranges,

and

tamarinds. We also got exceptionally fine specimens of the shell of the

King

conch and of the Queen conch. Hundreds of the King conch were piled up

at one

spot on the shore ready to be burnt into lime. The

natives appeared to be pure-blooded negroes of westcoast type, and in

some

respects their culture remains unchanged. For instance, the pestle and

mortar

and winnowing tray for treating maize were exactly similar in pattern

to those

we had seen used by the Akikuyu of Eastern Central Africa. When

catering, the price of each article is settled by negotiation, and it

is

definitely bought, as it is met with from time to time in our

perambulation, on

condition that it shall be paid for as it is passed into the boat on

departure

cash on delivery. Much other stuff, though unbought, is also brought

down to

the boat in the hope of sale at the last moment. This too is generally

taken as

well, because going cheaply, and also to avoid causing disappointment. Everybody

having been paid, and the already laden boat now pretty well

cluttered-up with

an unexpected additional cargo of chickens, eggs, fruit, shells, and

sundry

ethnological acquisitions, up goes the shoulder-of-mutton, the helmsman

ships

his twiddling-stick, and, in a few moments, the water is purring

beneath our

lee gunnel as the little craft slithers through the closely set

wavelets of

land-sheltered water. Long, narrow, and ballasted, these boats are very

fast

and are given the last ounce of wind pressure they can stand up to. It

seemed

to us, however, that her crew wished to show what they could do with

her as,

halliard and sheet in hand, they lifted the lee gunnel from moment to

moment,

just sufficiently to prevent her filling, but they did so with an easy

nonchalance that told that they were finished boat sailors. A very

few minutes saw us "once more aboard the lugger." We had left Mana at noon, and eight bells were

striking as the staysail-sheet-tackle scraped to leu'ard along the

hairless

belly of its horse; we had explored an island, seen a good deal of its

people

and their culture, and had revictualled ship, all within four hours,

yet

without hurry! Towards

sundown we passed out into the Atlantic, through the Crooked Island

Passage; at

8.45 p.m. the Light that marks the Passage dipped over our taffrail,

and we

turned in with that peace of mind which is the portion of those whose

ship is

clear of all land. This day,

April the 19th, Gibb's Hill Lighthouse, Bermuda, bore N. 42° E.,

distant 767

miles; it took us eleven days to do it. April the 20th. The

sargasso weed formed floating islands sometimes many acres in extent;

when one

considers the marine fauna that centres round a piece of floating

wreckage in

tropical seas, some idea can be formed of the wealth of life associated

with

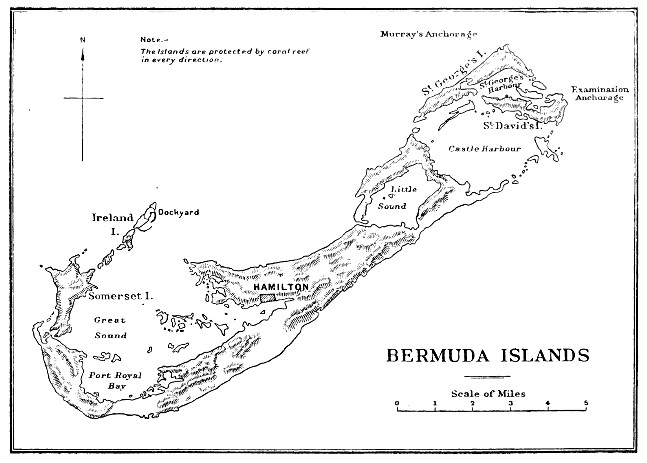

this vast sudd. Our patent log could no longer be towed. In 1609 attention was drawn

to them by Sir

George Somers, who was shipwrecked there on his way to Virginia, and

found them

"the most plentiful place that ever I came to for fish, hogs and

fowl." Fifty emigrants were sent out in 1612. Moore, a ship's

carpenter,

was the first governor. He established his headquarters at St.

George's. Later

a more central position was needed, and the town of Hamilton was laid

out, and

became the capital in 1815. The American War brought the islands into

notice

from a naval point of view, and in 1810 a dockyard was begun on Ireland

Island,

thousands of convicts being sent out from England for its construction.

The Colony possesses

representative

institutions, but not responsible government.  We made

Bermuda for the sake of gaining our northing. We had new canvas

awaiting us

there, that we ought to have received at Tahiti, and we had to decide,

on cable

advices, whether we would lay up Mana

here in Bermuda, in the United States of North America, or bring her

back to

England. The

Sailing Directions offered us two harbours, St. George's and Hamilton.

They do

not point out that all shipping business, practically all business, is

done at

Hamilton. We selected St. George's. The harbour master came aboard with

the

pilot, and proved an interesting man, kindly and obliging an old

soldier, a

keen conchologist, and a bit of a geologist. The harbour itself is

excellent

and charming; it extends away ad infinitum amongst

the islets and coral patches, but there is little indication of its

being made much use of by mercantile shipping. St.

George's Island is linked to its big neighbour by causeways and

bridges, which

are carried across the shallow coral sea. Its quaint, clean, sleepy

little

townlet, or village, exists by letting lodgings to American visitors,

and

growing early vegetables for exportation to the States. The

American Tourist is the winter migrant whose nature and idiosyncrasies

are by

the islanders most deeply studied. He, to the Bermudian, is Heaven's

choicest

gift his coconut the all-sufficing. Nine-tenths of the brain power of

the

islanders is devoted to inducing the creature to visit the islands and

to

keeping it contented whilst it is there, the other tenth to supplying

it with

early vegetables in its continental habitat. Of course Bermuda is an

important

naval station, and a certain amount of business is done in purveying to

the

naval and military establishments, but that is a thing apart. The

Dockyard is

situated on islands well removed from both St. George's and Hamilton.

In this

we may see the finger of Providence; placed elsewhere it would have

incommoded

the American Tourist. This cult

of the foreigner is the explanation of many things which at first sight

appear

strange in Bermuda. It is about eleven miles by road from St. George's

to

Hamilton, and there is no means of public conveyance beyond a covered

pair-horse wagonette, that act as a carrier's cart for goods and

passengers. We

marvelled exceedingly why this should be, whereupon it was thus

explained to us

by our butcher, who was also the proprietor of the shandy, ran express

aforesaid, and of a hired-carriage business, and by his son and

partner, the

M.P. for the St. George's Harbour Division. The Americans find the

climate of

Bermuda delightful as a winter resort. At Hamilton monster hotels are

built for

them, but there is nothing whatever for them to do. The islands do not

possess

any features of natural or historical interest that appeal to tourists.

Now the

islanders had observed that the dominant note in the American character

was its

restlessness; unless an American could violently rush around and spend

money he

was wretched and pined. But the island had excellent roads and lovely

views, so

they provided carriages, and objectives to drive to associated with

romance and

story, the evolution of which, from a basis of nothing, is a standing

testimony

to their intellectual creative powers, and of the truth of the axiom

that a

demand creates a supply. But the

island, for we may ignore the numerous islets, is very small. With care

and

good management, and by severely rationing him in the extent of his

daily shay

excursions, it was found that the American could be kept alive, and

healthy,

and cheerful for 14 days: from one steamer to the next: all this time

he exuded

dollars. "All is well," as the ant said to the aphis. Then suddenly

the heavens fell. A lewd spirit had prompted our friend the butcher of

St.

George's to import two motor-buses and with them run an hourly service

between

Port St. George and Hamilton, to the great convenience of the public,

and to his

own exceeding profit. As if this were not enough, he and others were

known to

have even placed orders in the States for motor-cars! Bitter was the

cry of the

carriage purveyors of Hamilton, of the hotels, of the furnished

apartments. The

American visitor would "do the darned island," every inch of its

roads, twice over, in a single day, and get away by the same boat he

had

arrived by (the boats stay two days loading vegetables). But where

shall salvation be found if not in "government of the people, by the

people,

for the people"? Many members of both Houses indirectly, and in some

cases

directly, were interested in the hired carriage, or apartment, or hotel

lines.

Trained in such schools for statesmen, the Legislature was able to

visualise

the national danger, and deal with it broadly, regardless of the vested

interests of the day. Without delay both Houses met, an Act was passed,

and the

Royal Assent given through the Governor, whereby the butcher was given

the cost

price of his two buses, and a solatium; the buses were immediately to

be sent

back to the States, and, for the future, no form of automobile was to

be

landed, owned, or used on the island. Heavy penalties for infraction.

So there

is still one spot on earth, anyhow, where one can escape the scourge of

the

motor-horn. For a few

days we stayed at St. George's, getting a little smith's work done and

watering

ship. There is no surface water on the island; the rain water is

collected and

stored in great underground cisterns hewn in the solid coral rock of

which the

island is formed. The water supply thus conserved has never been known

to fail.

In Mana's case the Military

Authorities kindly sent their large tank-boat alongside. At odd times

we

explored in the launch some of the labyrinth of waterways and islets

forming

part of St. George's Harbour, or connected with it. When doing so one

afternoon, we made the acquaintance, at nightfall, of a coloured

fisherman, by

offering him the courtesy of a pluck home. This man (Bartram of St.

George's)

proved an extraordinarily good fellow. He said he never worked on

Sundays,

therefore he was free to offer to take us on that day, as his guest, to

try for

monsters in a certain wonderful hole, far out on the edge of the reef,

a spot

we could reach with the aid of our launch. He was most keen about it,

so we

accepted. The monster-capturing was a failure, but he and his two sons

worked

hard all day, and seemed much concerned that they had failed to show

sport, nor

would they consider any suggestion of payment for their long day's

work, on our

return to the ship. They accepted, however, a clasp-knife each, as a

souvenir

of our excursion. Bartram

had told us that he had at home a wonderfully fine and rare "marine

specimen."

(The collection of "marine specimens" is one of the refuges of

despair of the American Tourist, and their supply has gradually become

a minor

industry of Bermuda.) He had found it some years ago. Many millionaires

from

the hotels or on yachts had offered him big prices for it, but the very

fact that

they were so keen to get it had made him all the more determined to

keep it.

Some day he had intended to sell it . Now would we accept it as a gift?

On

inspection it proved to be no coral, but a very fine example of a

colony of

sociable sea snails (Vermetus). We therefore suggested to Bartram that

we

should take it to England on Mana and

offer it in his name as a gift to the British Museum (Natural History).

This we

did, and Dr. Harmer, the Keeper of the Zoological Department, was much

pleased

with it, and wrote to Bartram accordingly. The

interest of this little story lies in the fact of its being a typical

example

of the way in which one often finds, in our remote dependencies, the

people

exhibiting unexpected keenness and pride in associating themselves with

England, and her interests, on an opportunity of doing so being pointed

out to

them. We had found it so at Pitcairn Island. A more

delightful place than Bermuda at which to spend a winter would be hard

to find

by those who care for pleasure sailing in smooth waters, fishing,

sunshine, and

the customary amenities of civilised life. Unhappily we could not spare

the

time to avail ourselves of the possibilities of St. George's. We had

constantly

to be at Hamilton on ship's business, so after several journeys to and

fro in

the dreadful covered wagonette, wherein physical discomfort almost

rendered us

indifferent to a kaleidoscopic succession of humorous persons,

situations, and

incidents, we got a pilot and went round under power into Hamilton

Harbour. Pilotage

is compulsory, but free. Once at Hamilton things went much more easily.

The

Colonial Authorities and the Admiral in Command and his Staff were most

kind

and hospitable. Admiralty House is a charming eighteenth-century

English

country residence, of moderate size, and romantically situated. In its

garden,

peeps of the sea are seen, through graceful subtropical foliage, at

every turn,

and miniature land-locked coves, reached from above by winding steps

down the

face of the falaise, afford the most perfect of boat harbours and

bathing-pools. Another

delightful official residence is allotted to the officer in command of

the

Dockyard. In his case he is given a miniature archipelago. His tiny

islands

rise from 20 to 100 feet above the water. On one is his house; another

is his

garden; chickens and pigs occupy a third, whilst his milch goats live

on

various small skerries. As the extent of water between the different

islets is

proportional to their size, and is deep, the whole makes a very

charming and

compact picture. Yet he is only ten minutes by bicycle from his office

in the

Dockyard, although, from his little kingdom, no sign of the Dockyard is

to be

seen, it being shut off by a wooded promontory. The

Admiral was good enough to offer us every facility for laying up Mana in the Dockyard, but on various

grounds we eventually decided to take war-time risks and bring her back

to

England, so receiving from him a signal-rocket outfit, and some kindly

advice

on the unwisdom of trying to run-down periscopes that showed no wake

behind

them, the vessel being now refreshed, at 0.55 p.m. on Friday, May the

12th,

1916, we weighed, and proceeded under power from Hamilton to the

Examination

Anchorage, with pilot aboard. Arriving there at 4.15 p.m. the Examining

Officer

came alongside and handed us the now usual special Admiralty clearance

card,

together with a courteous radiogram wishing us luck, from the Officer

in

Command of the Dockyard. The new trysail was hoisted, the engines

stopped, and

we commenced our voyage to Ponta Delgada in the Island of St. Miguel,

one of

the Azores, distant miles 1,869. This run

was of "yachting" character. Gentle breezes, smooth seas, an

occasional sail on the horizon. On the eighth day out, at the beginning

of the

first watch, the lights of St. Elmo were seen burning on both fore and

main

trucks. It is rather remarkable that this was the first, and only

occasion, on

which this phenomenon occurred throughout the entire voyage.

Occasionally we

got a turtle. Ten o'clock in the morning of the 30th of May showed us

the Peak

of Pico Island, 65 miles away, and at 10 p.m. next day, Thurs., May the

31st,

we hove-to off Ponta Delgada in the island of St. Miguel to await

daylight. The

1,869 miles had taken us 18 days. Having

been the victims of the organised dishonesty of the pilots of San

Francisco in

California, we had long before decided to run no risks of having the

vessel

again detained for ransom by foreign officials. Mana

therefore next day, June the ist, simply stood in and dropped

a boat outside the breakwater, and again stood off, whilst we pulled

in. Being

Good Friday, it was, of course, a fiesta,

all shops shut, and everybody away in the country. Our consul, too, was

away

for the day, but his wife kindly gave us our letters. We had been

instructed to

obtain from him the necessary information regarding war conditions, and

the

regulations governing shipping bound for British ports. At Bermuda

nothing was

known. When

pulling up the harbour, we had noticed one British vessel an armed

Government

transport, evidently formerly a small German passenger-carrying tramp

so

having bought some pineapples, vegetables and cigarettes, nothing else

being

procurable, we got into our boat and paid her a visit. Her commander

was ashore

for the day with the Consul fiestaing, but his Chief Officer was good

enough to

put us au courant with things, so we

bade adieu to Ponta Delgada without any wish to see more of it, and

pulled out

to sea. The ship was far away to leeward, set down by wind and current.

Not

expecting us to get through our work so quickly, she had not troubled

to keep

her station, but went off to argufy by flag with a Lloyd's

Signal-Station which

would not admit that she was in its book. After she

had picked us up one of the men left aboard asked whether any of the

craft in

the harbour were "a-hanging Judas." Though there were several small

square-rigged vessels alongside the Mole, none had, however,

cock-billed their

yards.1 It was interesting thus to find that the memory and

meaning

of the old sea custom still survived. Old superstitions and fancies

still

exist: an ancient shellback who was with us down to the s'uth'ard

reprobated

the capture of an albatross "They is the spurrits of drownded

seamen." Someone objected on doctrinal grounds, but was met with the

crushing rejoinder: "I said spurrits:

their souls ar' in 'ell." And now

we come to the last lap. On June the ist, by I p.m. we were again

aboard Mana, the boat hoisted in, and she bore

away to round Ferraira Point which forms the extremity of St. Michael's

Island.

From Ferraira's Point to the haven where we would be was no 1.5 miles,

and the

direction N.49Ό° E. true, or, shall we say. North East. After

making the customary routine entries in the Log Book associated with

taking

departure the latitude, the longitude, the reading of the patent log,

the

canvas set, etc. our Sailing-master makes the following entry, And

now we

are fairly on our way to Dear Old Britain. All the talk now is of the

submarine

risks. I put our chances of getting through unmolested at 85 per cent.

But is

the Mana doomed? Time will tell, but

I don't think." Nevertheless

every preparation was now made, in case we had to leave the ship in a

hurry, at

the orders of some German submarine. The engine was taken out of the

lifeboat

to save weight. Every detail both for her and the cutter was suitably

packed or

made up, and placed in the deck house, ready to be passed into her at

the last

moment before she was lowered. We could only afford room for the

photographic

negatives and papers of the Expedition. If the ship be sunk, the whole

of the

priceless, because irreplaceable, archaeological and ethnological

collections

must go with her. The men,

however, proceeded to pack, in their great seamen's bags, all the

clutter and

old rubbish they had accumulated during a voyage of over three years.

Its bulk

and weight would have rendered the boats unmanageable. Moreover, each

man, when

the time came, would be attending to shipping his property instead of

giving

all thought to getting his boat with her essential equipment safely

away from

the vessel. But we had taken them this long voyage without accident,

and we

were not going to let them make fools of themselves at the finish.

Moreover, Mana carried a pretty mixed crowd:

English, Spanish, Portuguese, and West Indian negroes, a Russian Finn,

and

descendants of the mutineers of the Bounty. At a pinch, amongst such a

lot,

long knives are apt to appear from nowhere, and self-control and

discipline be

at an end, with lamentable result. We therefore drew up a set of orders

in

triplicate; one copy for the fo'c's'le, one for aft, and one for entry

in the

official log, in which was clearly set out a routine that was to be

followed to

the letter in the event of our having to take to the boats. The details

need

not here be given, suffice to say that they stated that explicit orders

for the

common good were now set out in writing, and that THESE ORDERS WOULD

NOT, WHEN

THE OCCASION AROSE, BE REPEATED VERBALLY; that there was ample boat

accommodation for all, if the lifeboat were got away safely from the

ship

before the cutter, but not otherwise, because all hands were needed to

swing

out the larger boat. Therefore, when the ship's bell rang, the

Sailing-master

would take up his position by the lifeboat in the waist, to superintend

her

launching and stowage, and to give orders, and eventually to take

command of

her, and the Master would pick up his loaded repeating rifle and spare

cartridges in clips and go to the taffrail. (It was obvious from that

position

he could see and hear everything, and yet could not be approached or

rushed by

any, or many.) Any man

failing immediately to appear on deck when the bell rang would be shot

dead

without any warning when he did appear. Any man endeavouring to place

his

private gear in a boat would be shot dead in the act, without any

warning. The

like if he attempted to enter other than his own boat, or his own boat

out of

his turn. The like on a long knife, or other weapon, being seen in his

hand or

possession. The like on his failing to obey the verbal orders as

issued. By the

routine laid down the lifeboat would get away safely with her crew and

equipment. The cutter's own crew were strong enough to load and lower

their own

boat, after having assisted the heavy lifeboat, provided they obeyed

the orders

of the Mate who had charge of her. He was a good seaman, but it was

essential

that he should have the moral support that comes from a loaded rifle.

Once

boats all clear and safe, the lifeboat would pull in to the ship, as

close as

she thought wise, whereupon the "Old Man," in a nice cork jacket,

would drop off his taffrail into the water, and she would pick him up. These

orders and the penalties, extreme as they were, met with general

approval as

far as we could gather indirectly. Two days after their being posted,

when

Thomas, the coloured cook, came for orders, we thought we would put him

through

his catechism. Have you learnt up the orders in the fo'c's'le that

concern you,

Thomas? "Yes, sar! "When the bell rings, what will you

do? "Jump deck quick, damn quick,

sar!" "Good! And then?" "I go starnbig boat."

"And when she is in the water you'll jump into her? "No, sar! You

shoot Thomas. Cutter's my boat." Thomas had got up his orders

thoroughly

and intelligently, and departed quite pleased with his viva voce exam.,

and the

bundle of cigarettes his reward. Some of

the men, finding that their kit-bags must be left behind, hit out the

following

ingenious plan for saving their clothes. They first put on their Sunday

best

suit, over that their weekday go-ashore rig, then their working

clothes. To the

foregoing must be added a knitted guernsey or two, and any superior

underclothing. The result was most grotesque; they could hardly waddle,

or get

through the fo'c's'le hatch. Had the fine weather continued, their

sufferings

would have been severe. A gale, however, in which no submarine could

show her

nose, came to their rescue. At the time

we are writing of June 1916 the submarines were not operating far

out into

the Atlantic. Our idea was to keep Mana

well away until we got on to about the same parallel of latitude as the

Scilly

Isles, and then wait thereabouts until it blew hard from the S.W. Blow

it did,

sure enough, with high confused seas: dangerous. Gradually they became

bigger,

but less wicked. We rode it out dry and comfortably as usual, with

oil-bags to

wind'ard. Unhappily it was an Easterly gale, instead of the Westerly we

had

hoped for. It moderated. The wind drew to the Nor'ard. We let her go,

and sped

up the Channel at a great pace, and arrived in St. Helen's Roads, Isle

of

Wight, at noon on June the 23rd. Twenty-two days from St. Miguel. We

had

entered and passed up the English Channel, unchallenged by friend or

foe. In St.

Helen's Roads we took aboard the now obligatory Government pilot, who

brought

us through the different defences to the Hamble Spit Buoy, from which

we had

started three years and four months earlier. We had

traversed, almost entirely under canvas, without accident of

consequence to

ship or man, a distance of over One Hundred Thousand miles. Such is

the Mana of MANA. [The

Royal Cruising Club Challenge Cup, last held by Sunbeam

(Lord Brassey), was, in 1917, awarded to Mana on her

return, by special

resolution of the Annual General Meeting of the Club, for a remarkable

cruise

in the Pacific."]  |