| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

I: THE CELTS IN ANCIENT HISTORY Earliest References In

the chronicles of the classical nations for about five hundred years previous

to the Christian era there are frequent references to a people associated with

these nations, sometimes in peace, sometimes in war, and evidently occupying a

position of great strength and influence in the Terra Incognita of Mid-Europe.

This people is called by the Greeks the Hyperboreans or Celts, the latter term

being first found in the geographer Hecatæsus, about 500 B.C.1 Herodotus,

about half a century later, speaks of the Celts as dwelling “beyond the pillars

of Hercules” — i.e., in Spain — and also of the Danube as rising in their

country. Aristotle

knew that they dwelt “beyond Spain,” that they had captured Rome, and that they

set great store by warlike power. References other than geographical are

occasionally met with even in early writers. Hellanicus of Lesbos, an historian

of the fifth century B.C., describes the Celts as practising justice and

righteousness. Ephorus, about 350 B.C., has three lines of verse about the

Celts in which they are described as using “the same customs as the Greeks” — whatever

that may mean — and being on the friendliest terms with that people, who

established guest friendships among them. Plato, however, in the “Laws,”

classes the Celts among the races who are drunken and combative, and much

barbarity is attributed to them on the occasion of their irruption into Greece

and the sacking of Delphi in the year 273 B.C. Their attack on Rome and the sacking

of that city by them about a century earlier is one of the landmarks of ancient

history. The

history of this people during the time when they were the dominant power in

Mid-Europe has to be divined or reconstructed from scattered references, and

from accounts of episodes in their dealings with Greece and Rome, very much as

the figure of a primæval monster is reconstructed by the zoologist from a few

fossilised bones. No chronicles of their own have come down to us, no

architectural remains have survived; a few coins, and a few ornaments and

weapons in bronze decorated with enamel or with subtle and beautiful designs in

chased or repoussé work — these, and the names which often cling in strangely

altered forms to the places where they dwelt, from the Euxine to the British

Islands, are well-nigh all the visible traces which this once mighty power has

left us of its civilisation and dominion. Yet from these, and from the accounts

of classical writers, much can be deduced with certainty, and much more can be

conjectured with a very fair measure of probability. The great Celtic scholar

whose loss we have recently had to deplore, M. d’Arbois de Jubainville, has, on

the available data, drawn a convincing outline of Celtic history for the period

prior to their emergence into full historical light with the conquests of

Cæsar,2 and it is this outline of which the main features are

reproduced here. The True Celtic Race

To

begin with, we must dismiss the idea that Celtica was ever inhabited by a

single pure and homogeneous race. The true Celts, if we accept on this point

the carefully studied and elaborately argued conclusion of Dr. T. Rice Holmes,3

supported by the unanimous voice of antiquity, were a tall, fair race, warlike

and masterful,4 whose place of origin (as far as we can trace them)

was somewhere about the sources of the Danube, and who spread their dominion

both by conquest and by peaceful infiltration over Mid-Europe, Gaul, Spain, and

the British Islands. They did not exterminate the original prehistoric

inhabitants of these regions — palæolithic and neolithic races, dolmen-builders

and workers in bronze — but they imposed on them their language, their arts,

and their traditions, taking, no doubt, a good deal from them in return,

especially, as we shall see, in the important matter of religion. Among these

races the true Celts formed an aristocratic and ruling caste. In that capacity they

stood, alike in Gaul, in Spain, in Britain, and in Ireland, in the forefront or

armed opposition to foreign invasion. They bore the worst brunt of war, of

confiscations, and of banishment. They never lacked valour, but they were not

strong enough or united enough to prevail, and they perished in far greater

proportion than the earlier populations whom they had themselves subjugated.

But they disappeared also by mingling their blood with these inhabitants, whom

they impregnated with many of their own noble and virile qualities. Hence it

comes that the characteristics of the peoples called Celtic in the present day,

and who carry on the Celtic tradition and language, are in some respects so different

from those of the Celts of classical history and the Celts who produced the

literature and art of ancient Ireland, and in others so strikingly similar. To

take a physical characteristic alone, the more Celtic districts of the British

Islands are at present marked by darkness of complexion, hair, &c. They are

not very dark, but they are darker than the rest of the kingdom.5

But the true Celts were certainly fair. Even the Irish Celts of the twelfth

century are described by Giraldus Cambrensis as a fair race. Golden Age of the Celts

But

we are anticipating, and must return to the period of the origins of Celtic

history. As astronomers have discerned the existence of an unknown planet by

the perturbations which it has caused in the courses of those already under

direct observation, so we can discern in the fifth and fourth centuries before

Christ the presence of a great power and of mighty movements going on behind a

veil which will never be lifted now. This was the Golden Age of Celtdom in

Continental Europe. During this period the Celts waged three great and

successful wars, which had no little influence on the course of South European

history. About 500 B.C. they conquered Spain from the Carthaginians. A century

later we find them engaged in the conquest of Northern Italy from the

Etruscans. They settled in large numbers in the territory afterwards known as

Cisalpine Gaul, where many names, such as Mediolanum (Milan), Addua

(Adda), Virodunum (Verduno), and perhaps Cremona (creamh,

garlic)6, testify still to their occupation. They left a greater

memorial in the chief of Latin poets, whose name, Vergil, appears to bear

evidence of his Celtic ancestry.7 Towards the end of the fourth

century they overran Pannonia, conquering the Illyrians. Alliances with the Greeks

All

these wars were undertaken in alliance with the Greeks, with whom the Celts

were at this period on the friendliest terms. By the war with the Carthaginians

the monopoly held by that people of the trade in tin with Britain and in silver

with the miners of Spain was broken down, and the overland route across France

to Britain, for the sake of which the Phocæans had in 600 B.C. created the port

of Marseilles, was definitely secured to Greek trade. Greeks and Celts were at

this period allied against Phœnicians and Persians. The defeat of Hamilcar by

Gelon at Himera, in Sicily, took place in the same year as that of Xerxes at Salamis.

The Carthaginian army in that expedition was made up of mercenaries from half a

dozen different nations, but not a Celt is found in the Carthaginian ranks, and

Celtic hostility must have counted for much in preventing the Carthaginians

from lending help to the Persians for the overthrow of their common enemy.

These facts show that Celtica played no small part in preserving the Greek type

of civilisation from being overwhelmed by the despotisms of the East, and thus

in keeping alive in Europe the priceless seed of freedom and humane culture. Alexander the Great

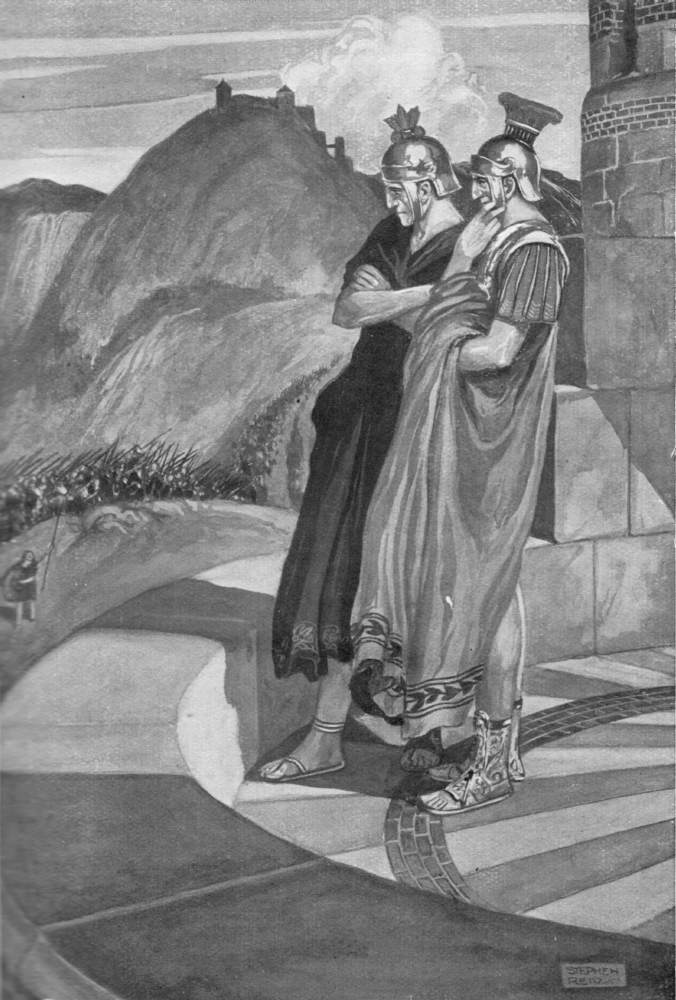

When

the counter-movement of Hellas against the East began under Alexander the Great

we find the Celts again appearing as a factor of importance. In

the fourth century Macedon was attacked and almost obliterated by Thracian and

Illyrian hordes. King Amyntas II. was defeated and driven into exile. His son Perdiccas

II. was killed in battle. When Philip, a younger brother of Perdiccas, came to

the obscure and tottering throne which he and his successors were to make the

seat of a great empire he was powerfully aided in making head against the

Illyrians by the conquests of the Celts in the valleys of the Danube and the

Po. The alliance was continued, and rendered, perhaps, more formal in the days

of Alexander. When about to undertake his conquest of Asia (334 B.C.) Alexander

first made a compact with the Celts “who dwelt by the Ionian Gulf” in order to secure

his Greek dominions from attack during his absence. The episode is related by

Ptolemy Soter in his history of the wars of Alexander.8 It has a

vividness which stamps it as a bit of authentic history, and another singular

testimony to the truth of the narrative has been brought to light by de

Jubainville. As the Celtic envoys, who are described as men of haughty bearing

and great stature, their mission concluded, were drinking with the king, he

asked them, it is said, what was the thing they, the Celts, most feared. The

envoys replied: “We fear no man: there is but one thing that we fear, namely,

that the sky should fall on us; but we regard nothing so much as the friendship

of a man such as thou.” Alexander bade them farewell, and, turning to his

nobles, whispered: “What a vainglorious people are these Celts!” Yet the

answer, for all its Celtic bravura and flourish, was not without both dignity

and courtesy. The reference to the falling of the sky seems to give a glimpse

of some primitive belief or myth of which it is no longer possible to discover

the meaning.9 The national oath by which the Celts bound themselves

to the observance of their covenant with Alexander is remarkable. “If we

observe not this engagement,” they said, “may the sky fall on us and crush us,

may the earth gape and swallow us up, may the sea burst out and overwhelm us.”

De Jubainville draws attention most appositely to a passage from the “Táin Bo Cuailgne,”

in the Book of Leinster,10 where the Ulster heroes declare to their

king, who wished to leave them in battle in order to meet an attack in another

part of the field: “Heaven is above us, and earth beneath us, and the sea is

round about us. Unless the sky shall fall with its showers of stars on the

ground where we are camped, or unless the earth shall be rent by an earthquake,

or unless the waves of the blue sea come over the forests of the living world,

we shall not give ground.”11 This survival of a peculiar

oath-formula for more than a thousand years, and its reappearance, after being

first heard of among the Celts of Mid-Europe, in a mythical romance of Ireland,

is certainly most curious, and, with other facts which we shall note hereafter,

speaks strongly for the community and persistence of Celtic culture.12 The Sack of Rome

We have mentioned two of the great wars of the Continental Celts; we come now to the third, that with the Etruscans, which ultimately brought them into conflict with the greatest power of pagan Europe, and led to their proudest feat of arms, the sack of Rome. About the year 400 B.C. the Celtic Empire seems to have reached the height of its power. Under a king named by Livy Ambicatus, who was probably the head of a dominant tribe in a military confederacy, like the German Emperor in the present day, the Celts seem to have been welded into a considerable degree of political unity, and to have followed a consistent policy. Attracted by the rich land of Northern Italy, they poured down through the passes of the Alps, and after hard fighting with the Etruscan inhabitants they maintained their ground there. At this time the Romans were pressing on the Etruscans from below, and Roman and Celt were acting in definite concert and alliance. But the Romans, despising perhaps the Northern barbarian warriors, had the rashness to play them false at the siege of Clusium, 391 B.C., a place which the Romans regarded as one of the bulwarks of Latium against the North. The Celts recognised Romans who had come to them in the sacred character of ambassadors fighting in the ranks of the enemy. The events which followed are, as they have come down to us, much mingled with legend, but there are certain touches of dramatic vividness in which the true character of the Celts appears distinctly recognisable. They applied, we are told, to Rome for satisfaction for the treachery of the envoys, who were three sons of Fabius Ambustus, the chief pontiff. The Romans refused to listen to the claim, and elected the Fabii military tribunes for the ensuing year. Then the Celts abandoned the siege of Clusium and marched straight on Rome. The army showed perfect discipline. There was no indiscriminate plundering and devastation, no city or fortress was assailed. “We are bound for Rome” was their cry to the guards upon the walls of the provincial towns, who watched the host in wonder and fear as it rolled steadily to the south. At last they reached the river Allia, a few miles from Rome, where the whole available force of the city was ranged to meet them. The battle took place on July 18, 390, that ill-omened dies Alliensis which long perpetuated in the Roman calendar the memory of the deepest shame the republic had ever known. The Celts turned the flank of the Roman army, and annihilated it in one tremendous charge. Three days later they were in Rome, and for nearly a year they remained masters of the city, or of its ruins, till a great fine had been exacted and full vengeance taken for the perfidy at Clusium. For nearly a century after the treaty thus concluded there was peace between the Celts and the Romans, and the breaking of that peace when certain Celtic tribes allied themselves with their old enemy, the Etruscans, in the third Samnite war was coincident with the breaking up of the Celtic Empire.13  "We are bound for Rome." Two

questions must now be considered before we can leave the historical part of

this Introduction. First of all, what are the evidences for the widespread

diffusion of Celtic power in Mid-Europe during this period? Secondly, where

were the Germanic peoples, and what was their position in regard to the Celts? Celtic Place-names in Europe

To

answer these questions fully would take us (for the purposes of this volume)

too deeply into philological discussions, which only the Celtic scholar can

fully appreciate. The evidence will be found fully set forth in de

Jubainville’s work, already frequently referred to. The study of European

place-names forms the basis of the argument. Take the Celtic name Noviomagus

composed of two Celtic words, the adjective meaning new, and magos

(Irish magh) a field or plain.14 There were nine places of this

name known in antiquity. Six were in France, among them the places now called

Noyon, in Oise, Nijon, in Vosges, Nyons, in Drôme. Three outside of France were

Nimègue, in Belgium, Neumagen, in the Rhineland, and one at Speyer, in the

Palatinate. The

word dunum, so often traceable in Gaelic place-names in the present day

(Dundalk, Dunrobin, &c.), and meaning fortress or castle, is another typically

Celtic element in European place-names. It occurred very frequently in France —

e.g., Lug-dunum (Lyons), Viro-dunum (Verdun). It is also found in

Switzerland — e.g., Minno-dunum (Moudon), Eburo-dunum (Yverdon) —

and in the Netherlands, where the famous city of Leyden goes back to a Celtic Lug-dunum.

In Great Britain the Celtic term was often changed by simple translation into castra;

thus Camulo-dunum became Colchester, Brano-dunum Brancaster. In

Spain and Portugal eight names terminating in dunum are mentioned by

classical writers. In Germany the modern names Kempton, Karnberg, Liegnitz, go

back respectively to the Celtic forms Cambo-dunum, Carro-aunum, Lugi-dunum,

and we find a Singi-dunum, now Belgrade, in Servia, a Novi-dunum,

now Isaktscha, in Roumania, a Carro-dunum in South Russia, near the

Dniester, and another in Croatia, now Pitsmeza. Sego-dunum, now Rodez,

in France, turns up also in Bavaria (Wurzburg), and in England (Sege-dunum,

now Wallsend, in Northumberland), and the first term, sego, is traceable

in Segorbe (Sego-briga) in Spain. Briga is a Celtic word, the

origin of the German burg, and equivalent in meaning to dunum. One

more example: the word magos, a plain, which is very frequent as an element

of Irish place-names, is found abundantly in France, and outside of France, in

countries no longer Celtic, it appears in Switzerland (Uro-magus now

Promasens), in the Rhineland (Broco-magus, Brumath), in the Netherlands,

as already noted (Nimègue), in Lombardy several times, and in Austria. The

examples given are by no means exhaustive, but they serve to indicate the wide

diffusion of the Celts in Europe and their identity of language over their vast

territory.15 Early Celtic Art

The

relics of ancient Celtic art-work tell the same story. In the year 1846 a great

pre-Roman necropolis was discovered at Hallstatt, near Salzburg, in Austria. It

contains relics believed by Dr. Arthur Evans to date from about 750 to 400 B.C.

These relics betoken in some cases a high standard of civilisation and

considerable commerce. Amber from the Baltic is there, Phoenician glass, and

gold-leaf of Oriental workmanship. Iron swords are found whose hilts and

sheaths are richly decorated with gold, ivory, and amber. The Celtic

culture illustrated by the remains at Hallstatt developed later into what is

called the La Tène culture. La Tène was a settlement at the north-eastern end

of the Lake of Neuchâtel, and many objects of great interest have been found

there since the site was first explored in 1858. These antiquities represent,

according to Dr. Evans, the culminating period of Gaulish civilisation, and

date from round about the third century B.C. The type of art here found must be

judged in the light of an observation recently made by Mr. Romilly Allen in his

“Celtic Art” (p. 13): “The

great difficulty in understanding the evolution of Celtic art lies in the fact

that although the Celts never seem to have invented any new ideas, they

possessed an extraordinary aptitude for picking up ideas from the different

peoples with whom war or commerce brought them into contact. And once the Celt

had borrowed an idea from his neighbours he was able to give it such a strong

Celtic tinge that it soon became something so different from what it was

originally as to be almost unrecognisable.”

Now

what the Celt borrowed in the art-culture which on the Continent culminated in

the La Tène relics were certain originally naturalistic motives for Greek

ornaments, notably the palmette and the meander motives. But it was

characteristic of the Celt that he avoided in his art all imitation of, or even

approximation to, the natural forms of the plant and animal world. He reduced

everything to pure decoration. What he enjoyed in decoration was the

alternation of long sweeping curves and undulations with the concentrated

energy of close-set spirals or bosses, and with these simple elements and with

the suggestion of a few motives derived from Greek art he elaborated a most

beautiful, subtle, and varied system of decoration, applied to weapons,

ornaments, and to toilet and household appliances of all kinds, in gold,

bronze, wood, and stone, and possibly, if we had the means of judging, to

textile fabrics also. One beautiful feature in the decoration of metal-work

seems to have entirely originated in Celtica. Enamelling was unknown to the

classical nations till they learned from the Celts. So late as the third

century A.D. it was still strange to the classical world, as we learn from the

reference of Philostratus: “They

say that the barbarians who live in the ocean [Britons] pour these colours upon

heated brass, and that they adhere, become hard as stone, and preserve the

designs that are made upon them.” Dr.

J. Anderson writes in the “Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of

Scotland”: “The Gauls as well as the Britons — of the

same Celtic stock — practised

enamel-working before the Roman conquest. The enamel workshops of Bibracte,

with their furnaces, crucibles, moulds,

polishing-stones, and with the crude enamels in their various stages of

preparation, have been recently excavated from the ruins of the city destroyed

by Caesar and his legions. But the Bibracte enamels are the work of mere

dabblers in the art, compared with the British examples. The home of the art

was Britain, and the style of the pattern, as well as the association in which

the objects decorated with it were found, demonstrated with certainty that it

had reached its highest stage of indigenous development before it came in

contact with the Roman culture.”16

The National Museum in Dublin contains many

superb examples of Irish decorative art in gold, bronze, and enamels, and the

“strong Celtic tinge” of which Mr. Romilly Allen speaks is as clearly

observable there as in the relics of Hallstatt or La Tène. Everything,

then, speaks of a community of culture, an identity of race-character, existing

over the vast territory known to the ancient world as “Celtica.” Celts and Germans

But,

as we have said before, this territory was by no means inhabited by the Celt

alone. In particular we have to ask, who and where were the Germans, the

Teuto-Gothic tribes, who eventually took the place of the Celts as the great

Northern menace to classical civilisation?

They

are mentioned by Pytheas, the eminent Greek traveller and geographer, about 300

B.C., but they play no part in history till, under the name of Cimbri and

Teutones, they descended on Italy to be vanquished by Marius at the close of

the second century. The ancient Greek geographers prior to Pytheas know nothing

of them, and assign all the territories now known as Germanic to various Celtic

tribes. The

explanation given by de Jubainville, and based by him on various philological considerations,

is that the Germans were a subject people, comparable to those “un-free tribes”

who existed in Gaul and in ancient Ireland. They lived under the Celtic

dominion, and had no independent political existence. De Jubainville finds that

all the words connected with law and government and war which are common both

to the Celtic and Teutonic languages were borrowed by the latter from the

former. Chief among them are the words represented by the modern German Reich,

empire, Amt, office, and the Gothic reiks, a king, all of which

are of unquestioned Celtic origin. De Jubainville also numbers among loan words

from Celtic the words Bann, an order; Frei, free; Geisel,

a hostage; Erbe, an inheritance; Werth, value; Weih,

sacred; Magus, a slave (Gothic); Wini, a wife (Old High German); Skalks,

Schalk, a slave (Gothic); Hathu, battle (Old German); Helith,

Held, a hero, from the same root as the word Celt; Heer, an army

(Celtic choris); Sieg, victory; Beute, booty; Burg,

a castle; and many others. The

etymological history of some of these words is interesting. Amt, for instance,

that word of so much significance in modern German administration, goes back to

an ancient Celtic ambhactos, which is compounded of the words ambi,

about, and actos, a past participle derived from the Celtic root AG,

meaning to act. Now ambi descends from the primitive Indo-European mbhi,

where the initial m is a kind of vowel, afterwards represented in

Sanscrit by a. This m vowel became n in those Germanic

words which derive directly from the primitive Indo-European tongue. But the

word which is now represented by amt appears in its earliest Germanic

form as ambaht, thus making plain its descent from the Celtic ambhactos. Again,

the word frei is found in its earliest Germanic form as frijo-s,

which comes from the primitive Indo-European prijo-s. The word here does

not, however, mean free; it means beloved (Sanscrit priya-s). In the

Celtic language, however, we find prijos dropping its initial p —

a difficulty in pronouncing this letter was a marked feature in ancient Celtic;

it changed j, according to a regular rule, into dd, and appears

in modern Welsh as rhydd = free. The Indo-European meaning persists in

the Germanic languages in the name of the love-goddess, Freia, and in

the word Freund, friend, Friede, peace. The sense borne by the

word in the sphere of civil right is traceable to a Celtic origin, and in that

sense appears to have been a loan from Celtic.

The

German Beute, booty, plunder, has had an instructive history. There was

a Gaulish word bodi found in compounds such as the place-name Segobodium

(Seveux), and various personal and tribal names, including Boudicca, better

known to us as the “British warrior queen,” Boadicea. This word meant anciently

“victory.” But the fruits of victory are spoil, and in this material sense the

word was adopted in German, in French (butin) in Norse (byte),

and the Welsh (budd). On the other hand, the word preserved its elevated

significance in Irish. In the Irish translation of Chronicles xxix. 11, where

the Vulgate original has “Tua est, Domine, magnificentia et potentia et gloria

et victoria,” the word victoria is rendered by the Irish búaidh,

and, as de Jubainville remarks, “ce n’est pas de butin qu’il s’agit.” He goes

on to say: “Búaidh has preserved in Irish, thanks to a vigorous and

persistent literary culture, the high meaning which it bore in the tongue of

the Gaulish aristocracy. The material sense of the word was alone perceived by the

lower classes of the population, and it is the tradition of this lower class

which has been preserved in the German, the French, and the Cymric languages.”17 Two

things, however, the Celts either could not or would not impose on the subjugated

German tribes — their language and their religion. In these two great factors

of race-unity and pride lay the seeds of the ultimate German uprising and

overthrow of the Celtic supremacy. The names of the German are different from

those of the Celtic deities, their funeral customs, with which are associated

the deepest religious conceptions of primitive races, are different. The Celts,

or at least the dominant section of them, buried their dead, regarding the use

of fire as a humiliation, to be inflicted on criminals, or upon slaves or

prisoners in those terrible human sacrifices which are the greatest stain on

their native culture. The Germans, on the other hand, burned their illustrious

dead on pyres, like the early Greeks — if a pyre could not be afforded for the

whole body, the noblest parts, such as the head and arms, were burned and the

rest buried. Downfall of the Celtic Empire

What

exactly took place at the time of the German revolt we shall never know;

certain it is, however, that from about the year 300 B.C. onward the Celts appear

to have lost whatever political cohesion and common purpose they had possessed.

Rent asunder, as it were, by the upthrust of some mighty subterranean force,

their tribes rolled down like lava-streams to the south, east, and west of

their original home. Some found their way into Northern Greece, where they

committed the outrage which so scandalised their former friends and allies in

the sack of the shrine of Delphi (273 B.C.). Others renewed, with worse

fortune, the old struggle with Rome, and perished in vast numbers at Sentinum

(295 B.C.) and Lake Vadimo (283 B.C.). One detachment penetrated into Asia

Minor, and founded the Celtic State of Galatia, where, as St. Jerome attests, a

Celtic dialect was still spoken in the fourth century A.D. Others enlisted as mercenary

troops with Carthage. A tumultuous war of Celts against scattered German

tribes, or against other Celts who represented earlier waves of emigration and

conquest, went on all over Mid-Europe, Gaul, and Britain. When this settled

down Gaul and the British Islands remained practically the sole relics of the

Celtic empire, the only countries still under Celtic law and leadership. By the

commencement of the Christian era Gaul and Britain had fallen under the yoke of

Rome, and their complete Romanisation was only a question of time. Unique Historical Position of

Ireland

Ireland

alone was never even visited, much less subjugated, by the Roman legionaries,

and maintained its independence against all comers nominally until the close of

the twelfth century, but for all practical purposes a good three hundred years

longer. Ireland

has therefore this unique feature of interest, that it carried an indigenous

Celtic civilisation, Celtic institutions, art, and literature, and the oldest

surviving form of the Celtic language,18 right across the chasm

which separates the antique from the modern world, the pagan from the Christian

world, and on into the full light of modern history and observation. The Celtic Character

The

moral no less than the physical characteristics attributed by classical writers

to the Celtic peoples show a remarkable distinctness and consistency. Much of

what is said about them might, as we should expect, be said of any primitive

and unlettered people, but there remains so much to differentiate them among

the races of mankind that if these ancient references to the Celts could be

read aloud, without mentioning the name of the race to whom they referred, to

any person acquainted with it through modern history alone, he would, I think,

without hesitation, name the Celtic peoples as the subject of the description

which he had heard. Some

of these references have already been quoted, and we need not repeat the

evidence derived from Plato, Ephorus, or Arrian. But an observation of M.

Porcius Cato on the Gauls may be adduced. “There are two things,” he says, “to

which the Gauls are devoted — the art of war and subtlety of speech” (“rem

militarem et argute loqui”). Cæsar’s Account

Cæsar

has given us a careful and critical account of them as he knew them in Gaul.

They were, he says, eager for battle, but easily dashed by reverses. They were

extremely superstitious, submitting to their Druids in all public and private

affairs, and regarding it as the worst of punishments to be excommunicated and

forbidden to approach thu ceremonies of religion: “They

who are thus interdicted [for refusing to obey a Druidical sentence] are

reckoned in the number of the vile and wicked; all persons avoid and fly their

company and discourse, lest they should receive any infection by contagion;

they are not permitted to commence a suit; neither is any post entrusted to

them.... The Druids are generally freed from military service, nor do they pay taxes

with the rest.... Encouraged by such rewards, many of their own accord come to

their schools, and are sent by their friends and relations. They are said there

to get by heart a great number of verses; some continue twenty years in their

education; neither is it held lawful to commit these things [the Druidic

doctrines] to writing, though in almost all public transactions and private accounts

they use the Greek characters.” The

Gauls were eager for news, besieging merchants and travellers for gossip,19

easily influenced, sanguine, credulous, fond of change, and wavering in their

counsels. They were at the same time remarkably acute and intelligent, very

quick to seize upon and to imitate any contrivance they found useful. Their

ingenuity in baffling the novel siege apparatus of the Roman armies is

specially noticed by Cæsar. Of their courage he speaks with great respect,

attributing their scorn of death, in some degree at least, to their firm faith

in the immortality of the soul.20 A people who in earlier days had

again and again annihilated Roman armies, had sacked Rome, and who had more

than once placed Cæsar himself in positions of the utmost anxiety and peril,

were evidently no weaklings, whatever their religious beliefs or practices.

Cæsar is not given to sentimental admiration of his foes, but one episode at

the siege of Avaricum moves him to immortalise the valour of the defence. A

wooden structure or agger had been raised by the Romans to overtop the

walls, which had proved impregnable to the assaults of the battering-ram. The Gauls

contrived to set this on fire. It was of the utmost moment to prevent the

besiegers from extinguishing the flames, and a Gaul mounted a portion of the

wall above the agger, throwing down upon it balls of tallow and pitch,

which were handed up to him from within. He was soon struck down by a missile

from a Roman catapult. Immediately another stepped over him as he lay, and

continued his comrade’s task. He too fell, but a third instantly took his

place, and a fourth; nor was this post ever deserted until the legionaries at

last extinguished the flames and forced the defenders back into the town, which

was finally captured on the following day.

Strabo on the Celts

The

geographer and traveller Strabo, who died 24 A.D., and was therefore a little

later than Cæsar, has much to tell us about the Celts. He notices that their

country (in this case Gaul) is thickly inhabited and well tilled — there is no

waste of natural resources. The women are prolific, and notably good mothers.

He describes the men as warlike, passionate, disputatious, easily provoked, but

generous and unsuspicious, and easily vanquished by stratagem. They showed

themselves eager for culture, and Greek letters and science had spread rapidly

among them from Massilia; public education was established in their towns. They

fought better on horseback than on foot, and in Strabo’s time formed the flower

of the Roman cavalry. They dwelt in great houses made of arched timbers with walls

of wickerwork — no doubt plastered with clay and lime, as in Ireland — and

thickly thatched. Towns of much importance were found in Gaul, and Cæsar notes

the strength of their walls, built of stone and timber. Both Cæsar and Strabo

agree that there was a very sharp division between the nobles and priestly or

educated class on the one hand and the common people on the other, the latter

being kept in strict subjection. The social division corresponds roughly, no

doubt, to the race distinction between the true Celts and the aboriginal

populations subdued by them. While Cæsar tells us that the Druids taught the

immortality of the soul, Strabo adds that they believed in the

indestructibility, which implies in some sense the divinity, of the material

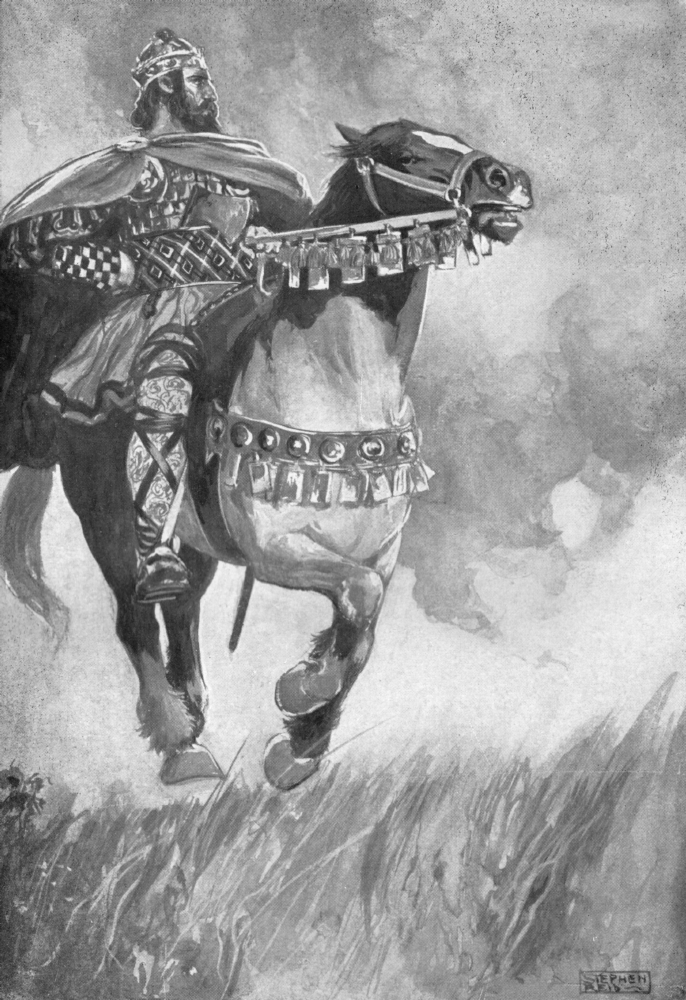

universe. The

Celtic warrior loved display. Everything that gave brilliance and the sense of

drama to life appealed to him. His weapons were richly ornamented, his

horse-trappings were wrought in bronze and enamel, of design as exquisite as

any relic of Mycenean or Cretan art, his raiment was embroidered with gold. The

scene of the surrender of Vercingetorix, when his heroic struggle with Rome had

come to an end on the fall of Alesia, is worth recording as a typically Celtic

blend of chivalry and of what appeared to the sober-minded Romans childish

ostentation.21 When he saw that the cause was lost he summoned a

tribal council, and told the assembled chiefs, whom he had led through a

glorious though unsuccessful war, that he was ready to sacrifice himself for

his still faithful followers — they might send his head to Cæsar if they liked,

or he would voluntarily surrender himself for the sake of getting easier terms

for his countrymen. The latter alternative was chosen. Vercingetorix then armed

himself with his most splendid weapons, decked his horse with its richest trappings,

and, after riding thrice round the Roman camp, went before Cæsar and laid at

his feet the sword which was the sole remaining defence of Gallic independence.

Cæsar sent him to Rome, where he lay in prison for six years, and was finally

put to death when Cæsar celebrated his triumph.

But

the Celtic love of splendour and of art were mixed with much barbarism. Strabo

tells us how the warriors rode home from victory with the heads of fallen

foemen dangling from their horses’ necks, just as in the Irish saga the Ulster

hero, Cuchulain, is represented as driving back to Emania from a foray into

Connacht with the heads of his enemies hanging from his chariot-rim. Their

domestic arrangements were rude; they lay on the ground to sleep, sat on

couches of straw, and their women worked in the fields. Polybius

A

characteristic scene from the battle of Clastidium (222 B.C.) is recorded by

Polybius. The Gæsati,22 he tells us, who were in the forefront of

the Celtic army, stripped naked for the fight, and the sight of these warriors,

with their great stature and their fair skins, on which glittered the collars

and bracelets of gold so loved as an adornment by all the Celts, filled the

Roman legionaries with awe. Yet when the day was over those golden ornaments

went in cartloads to deck the Capitol of Rome; and the final comment of

Polybius on the character of the Celts is that they, “I say not usually, but

always, in everything they attempt, are driven headlong by their passions, and

never submit to the laws of reason.” As might be expected, the chastity for

which the Germans were noted was never, until recent times, a Celtic

characteristic. Diodorus

Diodorus

Siculus, a contemporary of Julius Cæsar and Augustus, who had travelled in

Gaul, confirms in the main the accounts of Cæsar and Strabo, but adds some

interesting details. He notes in particular the Gallic love of gold. Even

cuirasses were made of it. This is also a very notable trait in Celtic Ireland,

where an astonishing number of prehistoric gold relics have been found, while

many more, now lost, are known to have existed. The temples and sacred places,

say Posidonius and Diodorus, were full of unguarded offerings of gold, which no

one ever touched. He mentions the great reverence paid to the bards, and, like

Cato, notices something peculiar about the kind of speech which the educated

Gauls cultivated: “they are not a talkative people, and are fond of expressing

themselves in enigmas, so that the hearer has to divine the most part of what

they would say.” This exactly answers to the literary language of ancient

Ireland, which is curt and allusive to a degree. The Druid was regarded as the prescribed

intermediary between God and man — no one could perform a religious act without

his assistance. Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus, who wrote much later, in the latter half of the fourth century A.D., had also visited Gaul, which was then, of course, much Romanised. He tells us, however, like former writers, of the great stature, fairness, and arrogant bearing of the Gallic warrior. He adds that the people, especially in Aquitaine, were singularly clean and proper in their persons — no one was to be seen in rags. The Gallic woman he describes as very tall, blue-eyed, and singularly beautiful; but a certain amount of awe is mingled with his evident admiration, for he tells us that while it was dangerous enough to get into a fight with a Gallic man, your case was indeed desperate if his wife with her “huge snowy arms,” which could strike like catapults, came to his assistance. One is irresistibly reminded of the gallery of vigorous, independent, fiery-hearted women, like Maeve, Grania, Findabair, Deirdre, and the historic Boadicea, who figure in the myths and in the history of the British Islands.  Rice Holmes on the Gauls The

following passage from Dr. Rice Holmes’ “Cæsar’s Conquest of Gaul” may be taken

as an admirable summary of the social physiognomy of that part of Celtica a

little before the time of the Christian era, and it corresponds closely to all

that is known of the native Irish civilisation:

“The

Gallic peoples had risen far above the condition of savages; and the Celticans

of the interior, many of whom had already fallen under Roman influence, had

attained a certain degree of civilisation, and even of luxury. Their trousers,

from which the province took its name of Gallia Bracata, and their

many-coloured tartan skirts and cloaks excited the astonishment of their

conquerors. The chiefs wore rings and bracelets and necklaces of gold; and when

these tall, fair-haired warriors rode forth to battle, with their helmets

wrought in the shape of some fierce beast’s head, and surmounted by nodding

plumes, their chain armour, their long bucklers and their huge clanking swords,

they made a splendid show. Walled towns or large villages, the strongholds of the

various tribes, were conspicuous on numerous hills. The plains were dotted by

scores of oper hamlets. The houses, built of timber and wickerwork, were large

and well thatched. The fields in summer were yellow with corn. Roads ran from

town to town. Rude bridges spanned the rivers; and barges laden with

merchandise floated along them. Ships clumsy indeed but larger than any that

were seen on the Mediterranean, braved the storms of the Bay of Biscay and

carried cargoes between the ports of Brittany and the coast of Britain. Tolls

were exacted on the goods which were transported on the great waterways; and it

was from the farming of these dues that the nobles derived a large part of

their wealth. Every tribe had its coinage; and the knowledge of writing in Greek

and Roman characters was not confined to the priests. The Æduans were familiar

with the plating of copper and of tin. The miners of Aquitaine, of Auvergne,

and of the Berri were celebrated for their skill. Indeed, in all that belonged

to outward prosperity the peoples of Gaul had made great strides since their

kinsmen first came into contact with Rome.”23 Weakness of the Celtic Policy Yet

this native Celtic civilisation, in many respects so attractive and so promising,

had evidently some defect or disability which prevented the Celtic peoples from

holding their own either against the ancient civilisation of the Græco-Roman

world, or against the rude young vigour of the Teutonic races. Let us consider

what this was. The Classical State

At

the root of the success of classical nations lay the conception of the civic

community, the πόλις, the res publica, as a kind of divine entity,

the foundation of blessing to men, venerable for its age, yet renewed in youth

with every generation; a power which a man might joyfully serve, knowing that

even if not remembered in its records his faithful service would outlive his

own petty life and go to exalt the life of his motherland or city for all

future time. In this spirit Socrates, when urged to evade his death sentence by

taking the means of escape from prison which his friends offered him, rebuked

them for inciting him to an impious violation of his country’s laws. For a

man’s country, he says, is more holy and venerable than father or mother, and

he must quietly obey the laws, to which he has assented by living under them

all his life, or incur the just wrath of their great Brethren, the Laws of the

Underworld, before whom, in the end, he must answer for his conduct on earth.

In a greater or less degree this exalted conception of the State formed the practical

religion of every man among the classical nations of antiquity, and gave to the

State its cohesive power, its capability of endurance and of progress. Teutonic Loyalty

With

the Teuton the cohesive force was supplied by another motive, one which was destined

to mingle with the civic motive and to form, in union with it — and often in

predominance over it — the main political factor in the development of the

European nations. This was the sentiment of what the Germans called Treue,

the personal fidelity to a chief, which in very early times extended itself to

a royal dynasty, a sentiment rooted profoundly in the Teutonic nature, and one

which has never been surpassed by any other human impulse as the source of

heroic self-sacrifice.

Celtic Religion

No

human influences are ever found pure and unmixed. The sentiment of personal

fidelity was not unknown to the classical nations. The sentiment of civic

patriotism, though of slow growth among the Teutonic races, did eventually

establish itself there. Neither sentiment was unknown to the Celt, but there

was another force which, in his case, overshadowed and dwarfed them, and

supplied what it could of the political inspiration and unifying power which

the classical nations got from patriotism and the Teutons from loyalty. This

was Religion; or perhaps it would be more accurate to say Sacerdotalism — religion

codified in dogma and administered by a priestly caste. The Druids, as we have

seen from Cæsar, whose observations are entirely confirmed by Strabo and by

references in Irish legends,24 were the really sovran power in

Celtica. All affairs, public and private, were subject to their authority, and

the penalties which they could inflict for any assertion of lay independence,

though resting for their efficacy, like the mediæval interdicts of the Catholic

Church, on popular superstition alone, were enough to quell the proudest

spirit. Here lay the real weakness of the Celtic polity. There is perhaps no

law written more conspicuously in the teachings of history than that nations who

are ruled by priests drawing their authority from supernatural sanctions are,

just in the measure that they are so ruled, incapable of true national

progress. The free, healthy current of secular life and thought is, in the very

nature of things, incompatible with priestly rule. Be the creed what it may,

Druidism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity, or fetichism, a priestly caste claiming

authority in temporal affairs by virtue of extra-temporal sanctions is

inevitably the enemy of that spirit of criticism, of that influx of new ideas,

of that growth of secular thought, of human and rational authority, which are

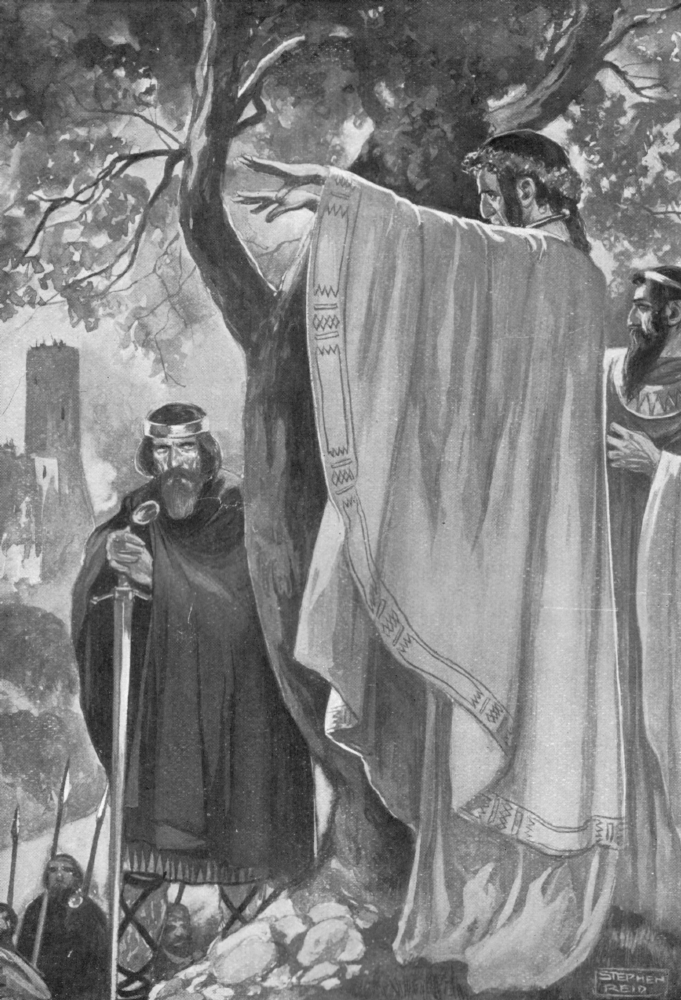

the elementary conditions of national development. The Cursing of Tara

A

singular and very cogent illustration of this truth can be drawn from the

history of the early Celtic world. In the sixth century A.D., a little over a

hundred years after the preaching of Christianity by St. Patrick, a king named

Dermot MacKerval25 ruled in Ireland. He was the Ard Righ, or High

King, of that country, whose seat of government was at Tara, in Meath, and

whose office, with its nominal

and legal superiority to the five provincial kings, represented the

impulse which was moving the Irish people towards a true national unity. The

first condition of such a unity was evidently the establishment of an effective

central authority. Such an authority, as we have said, the High King, in

theory, represented. Now it happened that one of his officers was murdered in

the discharge of his duty by a chief named Hugh Guairy. Guairy was the brother

of a bishop who was related by fosterage to St. Ruadan of Lorrha, and when King

Dermot sent to arrest the murderer these clergy found him a hiding-place.

Dermot, however, caused a search to be made, haled him forth from under the

roof of St. Ruadan, and brought him to Tara for trial. Immediately the ecclesiastics

of Ireland made common cause against the lay ruler who had dared to execute justice

on a criminal under clerical protection. They assembled at Tara, fasted against

the king,26 and laid their solemn malediction upon him and the seat

of his government. Then the chronicler tells us that Dermot’s wife had a

prophetic dream:  "Desolate be Tara for ever and ever!" “Upon

Tara’s green was a vast and wide-foliaged tree, and eleven slaves hewing at it;

but every chip that they knocked from it would return into its place again and

there adhere instantly, till at last there came one man that dealt the tree but

a stroke, and with that single cut laid it low.”27 The fair tree was the Irish monarchy, the

twelve hewers were the twelve Saints or Apostles of Ireland, and the one who

laid it low was St. Ruadan. The plea of the king for his country, whose fate he

saw to be hanging in the balance, is recorded with moving force and insight by

the Irish chronicler:28 “

‘Alas,’ he said, ‘for the iniquitous contest that ye have waged against me;

seeing that it is Ireland’s good that I pursue, and to preserve her discipline

and royal right; but ’tis Ireland’s unpeace and murderousness that ye endeavour

after.’ ” But Ruadan said, “Desolate be Tara for ever

and ever”; and the popular awe of the ecclesiastical malediction prevailed. The

criminal was surrendered, Tara was abandoned, and, except for a brief space

when a strong usurper, Brian Boru, fought his way to power, Ireland knew no

effective secular government till it was imposed upon her by a conqueror. The

last words of the historical tract from which we quote are Dermot’s cry of despair: This remarkable incident has been described at

some length because it is typical of a factor whose profound influence in

moulding the history of the Celtic peoples we can trace through a succession of

critical events from the time of Julius Caesar to the present day. How and

whence it arose we shall consider later; here it is enough to call attention to

it. It is a factor which forbade the national development of the Celts, in the

sense in which we can speak of that of the classical or the Teutonic peoples. What Europe Owes to the Celt

Yet

to suppose that on this account the Celt was not a force of any real consequence

in Europe would be altogether a mistake. His contribution to the culture of the

Western world was a very notable one. For some four centuries — about A.D. 500

to 900 — Ireland was the refuge of learning and the source of literary and

philosophic culture for half Europe. The verse-forms of Celtic poetry have

probably played the main part in determining the structure of all modern verse.

The myths and legends of the Gaelic and Cymric peoples kindled the imagination

of a host of Continental poets. True, the Celt did not himself create any great

architectural work of literature, just as he did not create a stable or imposing

national polity. His thinking and feeling were essentially lyrical and

concrete. Each object or aspect of life impressed him vividly and stirred him

profoundly; he was sensitive, impressionable to the last degree, but did not

see things in their larger and more far-reaching relations. He had little gift

for the establishment or institutions, for the service of principles; but he

was, and is, an indispensable and never-failing assertor of humanity as against

the tyranny of principles, the coldness and barrenness of institutions. The

institutions of royalty and of civic patriotism are both very capable of being

fossilised into barren formulae, and thus of fettering instead of inspiring the

soul. But the Celt has always been a rebel against anything that has not in it

the breath of life, against any unspiritual and purely external form of domination.

It is too true that he has been over-eager to enjoy the fine fruits of life

without the long and patient preparation for the harvest, but he has done and

will still do infinite service to the modern world in insisting that the true

fruit of life is a spiritual reality, never without pain and loss to be

obscured or forgotten amid the vast mechanism of a material civilisation. 1 He

speaks of “Nyrax, a Celtic city,” and “Massalia [Marseilles], a city of Liguria

in the land of the Celts” (“Fragmenta Hist. Græc.”). 2

In his “Premiers Habitants de l’Europe,” vol. ii. 3

“Cæesar’s Conquest of Gaul,” pp. 251-327.

4

The ancients were not very close observers of physical characteristics. They

describe the Celts in almost exactly the same terms as those which they apply

to the Germanic races. Dr. Rice Holmes is of opinion that the real difference,

physically, lay in the fact that the fairness of the Germans was blond, and

that of the Celts red. In an interesting passage of the work already quoted (p.

315) he observes that, “Making every allowance for the admixture of other

blood, which must have considerably modified the type of the original Celtic or

Gallic invaders of these islands, we are struck by the fact that among all our

Celtic-speaking fellow subjects there are to be found numerous specimens of a

type which also exists in those parts of Brittany which were colonised by

British invaders, and in those parts of Gaul in which the Gallic invaders

appear to have settled most thickly, as well as in Northern Italy, where the

Celtic invaders were once dominant; and also by the fact that this type, even

among the more blond representatives of it, is strikingly different, to the

casual as well as to the scientific observer, from that of the purest

representatives of the ancient Germans. The well-known picture of Sir David

Wilkie, ‘Reading of the Waterloo Gazette,’ illustrates, as Daniel Wilson

remarked, the difference between the two types. Put a Perthshire Highlander

side by side with a Sussex farmer. Both will be fair; but the red hair and

beard of the Scot will be in marked contrast with the fair hair of the

Englishman, and their features will differ still more markedly. I remember

teeing two gamekeepers in a railway carriage running from Inverness to Lairey.

They were tall, athletic, fair men, evidently belonging to the Scandinavian

type, which, as Dr. Beddoe says, is so common in the extreme north of Scotland;

but both in colouring and in general aspect they were utterly different from

the tall, fair Highlanders whom I had seen in Perthshire. There was not a trace

of red in their hair, their long beards being absolutely yellow. The prevalence

of red among the Celtic-speaking people is, it seems to me, a most striking

characteristic. Not only do we find eleven men in every hundred whose hair is

absolutely red, but underlying the blacks and the dark browns the lame tint is

to be discovered.” 5

See the map of comparative nigrescence given in Ripley’s “Races of Europe,” p.

318. In France, however, the Bretons are not a dark race relatively to the rest

of the population. They are composed partly of the ancient Gallic peoples and

partly of settlers from Wales who were driven out by the Saxon invasion. 6

See for these names Holder’s “Altceltischer Sprachschatz.” 7

Vergil might possibly mean “the very-bright” or illustrious one, a natural form

for a proper name. Ver in Gallic names (Vercingetorix,

Vercassivellasimus, &c.) is often an intensive prefix, like the modern

Irish fior. The name of the village where Vergil was born, Andes (now

Pietola), is Celtic. His love of nature, his mysticism, and his strong feeling

for a certain decorative quality in language and rhythm are markedly Celtic

qualities. Tennyson’s phrases for him, “landscape-lover, lord of language,” are

suggestive in this connexion. 8

Ptolemy, a friend, and probably, indeed, half-brother, of Alexander, was

doubtless present when this incident took place. His work has not survived, but

is quoted by Arrian and other historians.

9

One is reminded of the folk-tale about Henny Penny, who went to tell the king

that the sky was falling. 10

The Book of Leinster is a manuscript of the twelfth century. The version of the

“Táin” given in it probably dates from the eighth. See de Jubainville,

“Premiers Habitants,” ii. 316. 11

Dr. Douglas Hyde in his “Literary History of Ireland” (p. 7) gives a slightly

different translation. 12

It is also a testimony to the close accuracy of the narrative of Ptolemy. 13

Roman history tells of various conflicts with the Celts during this period, but

de Jubainville has shown that these narratives are almost entirely mythical.

See “Premiers Habitants,” ii. 318-323. 14

E.g., Moymell (magh-meala), the Plain of Honey, a Gaelic name for

Fairyland, and many place-names. 15

For these and many other examples see de Jubainville’s “Premiers Habitants,”

ii. 255 sqq. 16

Quoted by Mr. Romilly Allen in “Celtic Art,” p. 136. 17

“Premiers Habitants,” ii. 355, 356. 18

Irish is probably an older form of Celtic speech than Welsh. This is shown by

many philological peculiarities of the Irish language, of which one of the most

interesting may here be briefly referred to. The Goidelic or Gaelic Celts, who,

according to the usual theory, first colonised the British Islands, and who

were forced by successive waves of invasion by their Continental kindred to the

extreme west, had a peculiar dislike to the pronunciation of the letter p.

Thus the Indo-European particle pare, represented by Greek παρά,

beside or close to, becomes in early Celtic are, as in the name Are-morici

(the Armoricans, those who dwell ar muir, by the sea); Are-dunum

(Ardin, in France); Are-cluta, the place beside the Clota (Clyde), now

Dumbarton; Are-taunon, in Germany (near the Taunus Mountains), &c.

When this letter was not simply dropped it was usually changed into c (k,

g). But about the sixth century B.C. a remarkable change passed over the

language of the Continental Celts. They gained in some unexplained way the faculty

for pronouncing p, and even substituted it for existing c sounds; thus the original Cretanis

became Pretanis, Britain, the numeral qetuares (four) became petuares,

and so forth. Celtic place-names in Spain show that this change must have taken

place before the Celtic conquest of that country, 500 B.C. Now a comparison of

many Irish and Welsh words shows distinctly this avoidance of p on the

Irish side and lack of any objection to it on the Welsh. The following are a

few illustrations:

19

The Irish, says Edmund Spenser, in his “View of the Present State of Ireland,”

“use commonyle to send up and down to know newes, and yf any meet with another,

his second woorde is, What newes?” 20

Compare Spenser: “I have heard some greate warriors say, that in all the

services which they had seen abroad in forrayne countreys, they never saw a

more comely horseman than the Irish man, nor that cometh on more bravely in his

charge ... they are very valiante and hardye, for the most part great endurours

of cold, labour, hunger and all hardiness, very active and stronge of hand,

very swift of foote, very vigilaunte and circumspect in theyr enterprises, very

present in perrils, very great scorners of death.” 21

The scene of the surrender of Vercingetorix is not recounted by Cæsar, and

rests mainly on the authority of Plutarch and of the historian Florus, but it

is accepted by scholars (Mommsen, Long, &c.) as historic. 22

These were a tribe who took their name from the gæsum, a kind of Celtic

javelin, which was their principal weapon. The torque, or twisted collar of

gold, is introduced as a typical ornament in the well-known statue of the dying

Gaul, commonly called “The Dying Gladiator.” Many examples are preserved in the

National Museum of Dublin. 23

“Cæsar’s Conquest of Gaul,” pp. 10, 11. Let it be added that the aristocratic

Celts were, like the Teutons, dolichocephalic — that is to say, they had heads

long in proportion to their breadth. This is proved by remains found in the

basin of the Marne, which was thickly populated by them. In one case the skeleton

of the tall Gallic warrior was found with his war-car, iron helmet, and sword,

now in the Music de St.-Germain. The inhabitants of the British Islands are

uniformly long-headed, the round-headed “Alpine” type occurring very rarely.

Those of modern France are round-headed. The shape of the head, however, is now

known to be by no means a constant racial character. It alters rapidly in a new

environment, as is shown by measurements of the descendants of immigrants in

America. See an article on this subject by Professor Haddon in “Nature,” Nov.

3, 1910. 24

In the “Tain Bo Cuailgne,” for instance, the King of Ulster must not speak to a

messenger until the Druid, Cathbad, has questioned him. One recalls the lines

of Sir Samuel Ferguson in his Irish epic poem, “Congal”: “... For ever since the time When

Cathbad smothered Usnach’s sons in that foul sea of slime Raised by abominable

spells at Creeveroe’s bloody gate, Do ruin and dishonour still on priest-led

kings await.” 25

Celtice, Diarmuid mac Cearbhaill.

26

It was the practice, known in India also, for a person who was wronged by a

superior, or thought himself so, to sit before the doorstep of the denier of

justice and fast until right was done him. In Ireland a magical power was

attributed to the ceremony, the effect of which would be averted by the other

person fasting as well. 27

“Silva Gadelica,” by S.H. O’Grady, p. 73.

28

The authority here quoted is a narrative contained in a fifteenth-century

vellum manuscript found in Lismore Castle in 1814, and translated by S.H.

O’Grady in his “Silva Gadelica.” The narrative is attributed to an officer of

Dermot’s court. |