| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Myths & Legends: The Celtic Race Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

II: THE RELIGION OF THE CELTS Ireland and the Celtic Religion

We

have said that the Irish among the Celtic peoples possess the unique interest

of having carried into the light of modern historical research many of the

features of a native Celtic civilisation. There is, however, one thing which

they did not carry across the gulf which divides us from the ancient world — and

this was their religion. It

was not merely that they changed it; they left it behind them so entirely that

all record of it is lost. St. Patrick, himself a Celt, who apostolised Ireland

during the fifth century, has left us an autobiographical narrative of his

mission, a document of intense interest, and the earliest extant record of

British Christianity; but in it he tells us nothing of the doctrines he came to

supplant. We learn far more of Celtic religious beliefs from Julius Cæsar, who

approached them from quite another side. The copious legendary literature which

took its present form in Ireland between the seventh and the twelfth centuries,

though often manifestly going back to pre-Christian sources, shows us, beyond a

belief in magic and a devotion to certain ceremonial or chivalric observances, practically

nothing resembling a religious or even an ethical system. We know that certain

chiefs and bards offered a long resistance to the new faith, and that this

resistance came to the arbitrament of battle at Moyrath in the sixth century,

but no echo of any intellectual controversy, no matching of one doctrine

against another, such as we find, for instance, in the records of the

controversy of Celsus with Origen, has reached us from this period of change

and strife. The literature of ancient Ireland, as we shall see, embodied many

ancient myths; and traces appear in it of beings who must, at one time, have

been gods or elemental powers; but all has been emptied of religious

significance and turned to romance and beauty. Yet not only was there, as Cæsar

tells us, a very well-developed religious system among the Gauls, but we learn

on the same authority that the British Islands were the authoritative centre of

this system; they were, so to speak, the Rome of the Celtic religion. What

this religion was like we have now to consider, as an introduction to the myths

and tales which more or less remotely sprang from it. The Popular Religion of the Celts

But

first we must point out that the Celtic religion was by no means a simple

affair, and cannot be summed up as what we call “Druidism.” Beside the official

religion there was a body of popular superstitions and observances which came

from a deeper and older source than Druidism, and was destined long to outlive

it — indeed, it is far from dead even yet.

The Megalithic People

The

religions of primitive peoples mostly centre on, or take their rise from, rites

and practices connected with the burial of the dead. The earliest people

inhabiting Celtic territory in the West of Europe of whom we have any distinct

knowledge are a race without name or known history, but by their sepulchral

monuments, of which so many still exist, we can learn a great deal about them.

They were the so-called Megalithic People,1 the builders of dolmens,

cromlechs, and chambered tumuli, of which more than three thousand have been

counted in France alone. Dolmens are found from Scandinavia southwards, all

down the western lands of Europe to the Straits of Gibraltar, and round by the

Mediterranean coast of Spain. They occur in some of the western islands of the Mediterranean,

and are found in Greece, where, in Mycenæ, an ancient dolmen yet stands beside

the magnificent burial-chamber of the Atreidae. Roughly, if we draw a line from

the mouth of the Rhone northward to Varanger Fiord, one may say that, except

for a few Mediterranean examples, all the dolmens in Europe lie to the west of

that line. To the east none are found till we come into Asia. But they cross

the Straits of Gibraltar, and are found all along the North African littoral,

and thence eastwards through Arabia, India, and as far as Japan. Dolmens, Cromlechs, and Tumuli

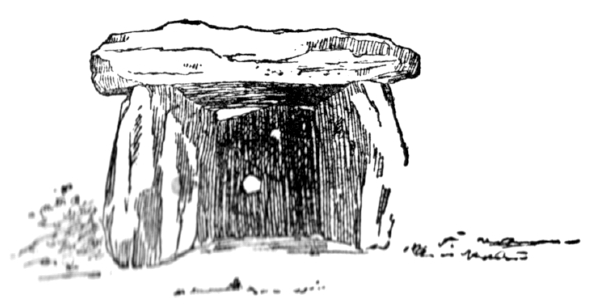

A dolmen, it may be here explained, is a kind

of chamber composed of upright unhewn stones, and roofed generally with a

single huge stone. They are usually wedge-shaped in plan, and traces of a porch

or vestibule can often be noticed. The primary intention of the dolmen was to

represent a house or dwelling-place for the dead. A cromlech (often confused in

popular language with the dolmen) is properly a circular arrangement of standing

stones, often with a dolmen in their midst. It is believed that most if not all

of the now exposed dolmens were originally covered with a great mound of earth

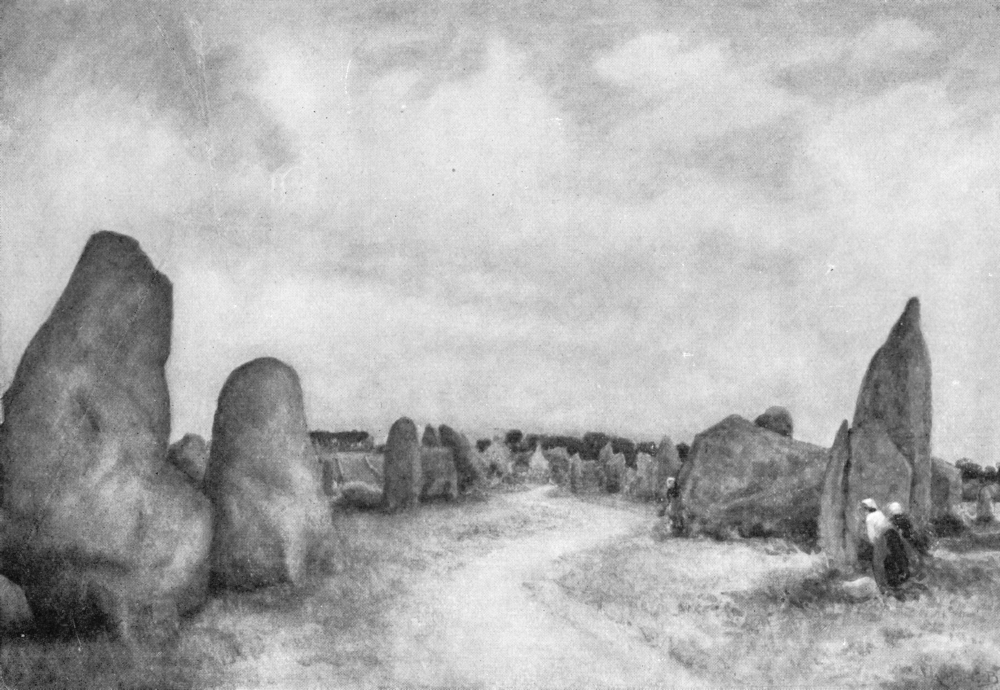

or of smaller stones. Sometimes, as in the illustration we give from Carnac, in

Brittany, great avenues or alignments are formed of single upright stones, and

these, no doubt, had some purpose connected with the ritual of worship carried

on in the locality. The later megalithic monuments, as at Stonehenge, may be of

dressed stone, but in all cases their rudeness of construction, the absence of

any sculpturing (except for patterns or symbols incised on the surface), the

evident aim at creating a powerful impression by the brute strength of huge

monolithic masses, as well as certain subsidiary features in their design which

shall be described later on, give these megalithic monuments a curious family likeness

and mark them out from the chambered tombs of the early Greeks, of the

Egyptians, and of other more advanced races. The dolmens proper gave place in

the end to great chambered mounds or tumuli, as at New Grange, which we also

reckon as belonging to the Megalithic People. They are a natural development of

the dolmen. The early dolmen-builders were in the neolithic stage of culture,

their weapons were of polished stone. But in the tumuli not only stone, but

also bronze, and even iron, instruments are found — at first evidently

importations, but afterwards of local manufacture.  Dolmen at Proleek, Ireland (After Borlase) Origin of the Megalithic People

The language originally spoken by this people

can only be conjectured by the traces of it left in that of their conquerors,

the Celts.2 But a map of the distribution or their monuments

irresistibly suggests the idea that their builders were of North African

origin; that they were not at first accustomed to traverse the sea for any

great distance; that they migrated westwards along North Africa, crossed into

Europe where the Mediterranean at Gibraltar narrows to a strait of a few miles

in width, and thence spread over the western regions of Europe, including the British

Islands, while on the eastward they penetrated by Arabia into Asia. It must,

however, be borne in mind that while originally, no doubt, a distinct race, the

Megalithic People came in the end to represent, not a race, but a culture. The

human remains found in these sepulchres, with their wide divergence in the

shape of the skull, &c., clearly prove this.3 These and other

relics testify to the dolmen-builders in general as representing a superior and

well-developed type, acquainted with agriculture, pasturage, and to some extent

with seafaring. The monuments themselves, which are often of imposing size and

imply much thought and organised effort in their construction, show

unquestionably the existence, at this period, of a priesthood charged with the

care of funeral rites and capable of controlling large bodies of men. Their

dead were, as a rule, not burned, but buried whole — the greater monuments

marking, no doubt, the sepulchres of important personages, while the common

people were buried in tombs of which no traces now exist.

Photograph by R. Welch, Belfast The Celts of the Plains

De

Jubainville, in his account of the early history of the Celts, takes account of

two main groups only — the Celts and the Megalithic People. But A. Bertrand, in

his very valuable work “La Religion des Gaulois,” distinguishes two elements

among the Celts themselves. There are, besides the Megalithic People, the two

groups of lowland Celts and mountain Celts. The lowland Celts, according to his

view, started from the Danube and entered Gaul probably about 1200 B.C. They

were the founders of the lake-dwellings in Switzerland, in the Danube valley,

and in Ireland. They knew the use of metals, and worked in gold, in tin, in

bronze, and towards the end of their period in iron. Unlike the Megalithic

People, they spoke a Celtic tongue,4 though Bertrand seems to doubt

their genuine racial affinity with the true Celts. They were perhaps Celticised

rather than actually Celtic. They were not warlike; a quiet folk of herdsmen,

tillers, and artificers. They did not bury, but burned their dead. At a great settlement

of theirs, Golasecca, in Cisalpine Gaul, 6000 interments were found. In each

case the body had been burned; there was not a single burial without previous

burning. This

people entered Gaul not (according to Bertrand), for the most part, as

conquerors, but by gradual infiltration, occupying vacant spaces wherever they

found them along the valleys and plains. They came by the passes of the Alps,

and their starting-point was the country of the Upper Danube, which Herodotus

says “rises among the Celts.” They blended peacefully with the Megalithic

People among whom they settled, and did not evolve any of those advanced

political institutions which are only nursed in war, but probably they

contributed powerfully to the development of the Druidical system of religion

and to the bardic poetry. The Celts of the Mountains

Finally,

we have a third group, the true Celtic group, which followed closely on the

track of the second. It was at the beginning of the sixth century that it first

made its appearance on the left bank of the Rhine. While Bertrand calls the

second group Celtic, these he styles Galatic, and identifies them with the

Galatæ of the Greeks and the Galli and Belgæ of the Romans. The

second group, as we have said, were Celts of the plains. The third were Celts

of the mountains. The earliest home in which we know them was the ranges of the

Balkans and Carpathians. Their organisation was that of a military aristocracy

— they lorded it over the subject populations on whom they lived by tribute or

pillage. They are the warlike Celts of ancient history — the sackers of Rome

and Delphi, the mercenary warriors who fought for pay and for the love of

warfare in the ranks of Carthage and afterwards of Rome. Agriculture and

industry were despised by them, their women tilled the ground, and under their

rule the common population became reduced almost to servitude; “plebs pœne

servorum habetur loco,” as Caesar tells us. Ireland alone escaped in some

degree from the oppression of this military aristocracy, and from the sharp

dividing line which it drew between the classes, yet even there a reflexion of

the state of things in Gaul is found, even there we find free and unfree tribes

and oppressive and dishonouring exactions on the part of the ruling order. Yet,

if this ruling race had some of the vices of untamed strength, they had also

many noble and humane qualities. They were dauntlessly brave, fantastically

chivalrous, keenly sensitive to the appeal of poetry, of music, and of

speculative thought. Posidonius found the bardic institution flourishing among

them about 100 B.C., and about two hundred years earlier Hecatæus of Abdera

describes the elaborate musical services held by the Celts in a Western island

— probably Great Britain — in honour of their god Apollo (Lugh).5

Aryan of the Aryans, they had in them the making of a great and progressive

nation; but the Druidic system — not on the side of its philosophy and science,

but on that of its ecclesiastico-political organisation — was their bane, and

their submission to it was their fatal weakness. The

culture of these mountain Celts differed markedly from that of the lowlanders.

Their age was the age of iron, not of bronze; their dead were not burned (which

they considered a disgrace), but buried.

The

territories occupied by them in force were Switzerland, Burgundy, the Palatinate,

and Northern France, parts of Britain to the west, and Illyria and Galatia to

the east, but smaller groups of them must have penetrated far and wide through

all Celtic territory, and taken up a ruling position wherever they went.  Arthur G. Bell The Religion of Magic

This

triple division is reflected more or less in all the Celtic countries, and must

always be borne in mind when we speak of Celtic ideas and Celtic religion, and

try to estimate the contribution of the Celtic peoples to European culture. The

mythical literature and the art of the Celt have probably sprung mainly from

the section represented by the Lowland Celts of Bertrand. But this literature

of song and saga was produced by a bardic class for the pleasure and

instruction of a proud, chivalrous, and warlike aristocracy, and would thus

inevitably be moulded by the ideas of this aristocracy. But it would also have

been coloured by the profound influence of the religious beliefs and

observances entertained by the Megalithic People — beliefs which are only now

fading slowly away in the spreading daylight of science. These beliefs may be summed

up in the one term Magic. The nature of this religion of magic must now be

briefly discussed, for it was a potent element in the formation of the body of

myths and legends with which we have afterwards to deal. And, as Professor Bury

remarked in his Inaugural Lecture at Cambridge, in 1903: “For

the purpose of prosecuting that most difficult of all inquiries, the ethnical problem, the part

played by race in the development of

peoples and the effects of race-blendings, it must be remembered that the Celtic world

commands one of the chief portals of ingress into that mysterious pre-Aryan

foreworld, from which it may well be that we modern Europeans have inherited

far more than we dream.” The ultimate root of the word Magic is

unknown, but proximately it is derived from the Magi, or priests of Chaldea and

Media in pre-Aryan and pre-Semitic times, who were the great exponents of this

system of thought, so strangely mingled of superstition, philosophy, and

scientific observation. The fundamental conception of magic is that of the

spiritual vitality of all nature. This spiritual vitality was not, as in

polytheism, conceived as separated from nature in distinct divine

personalities. It was implicit and immanent in nature; obscure, undefined,

invested with all the awfulness of a power whose limits and nature are enveloped

in impenetrable mystery. In its remote origin it was doubtless, as many facts appear

to show, associated with the cult of the dead, for death was looked upon as the

resumption into nature, and as the investment with vague and uncontrollable

powers, of a spiritual force formerly embodied in the concrete, limited,

manageable, and therefore less awful form of a living human personality. Yet

these powers were not altogether uncontrollable. The desire for control, as

well as the suggestion of the means for achieving it, probably arose from the

first rude practices of the art of healing. Medicine of some sort was one of

the earliest necessities of man. And the power of certain natural substances,

mineral or vegetable, to produce bodily and mental effects often of a most

startling character would naturally be taken as signal evidence of what we may

call the “magical” conception of the universe.6 The first magicians

were those who attained a special knowledge of healing or poisonous herbs; but “virtue”

of some sort being attributed to every natural object and phenomenon, a kind of

magical science, partly the child of true research, partly of poetic

imagination, partly of priestcraft, would in time spring up, would be codified

into rites and formulas, attached to special places and objects, and

represented by symbols. The whole subject has been treated by Pliny in a

remarkable passage which deserves quotation at length: Pliny on the Religion of Magic

“Magic

is one of the few things which it is important to discuss at some length, were

it only because, being the most delusive of all the arts, it has everywhere and

at all times been most powerfully credited. Nor need it surprise us that it has

obtained so vast an influence, for it has united in itself the three arts which

have wielded the most powerful sway over the spirit of man. Springing in the

first instance from Medicine — a fact which no one can doubt — and under cover

of a solicitude for our health, it has glided into the mind, and taken the form

of another medicine, more holy and more profound. In the second place, bearing

the most seductive and flattering promises, it has enlisted the motive of Religion,

the subject on which, even at this day, mankind is most in the dark. To crown

all it has had recourse to the art of Astrology; and every man is eager to know

the future and convinced that this knowledge is most certainly to be obtained

from the heavens. Thus, holding the minds of men enchained in this triple bond,

it has extended its sway over many nations, and the Kings of Kings obey it in

the East. “In the East, doubtless, it was invented — in

Persia and by Zoroaster.7 All the authorities agree in this. But has

there not been more than one Zoroaster?... I have noticed that in ancient

times, and indeed almost always, one finds men seeking in this science the

climax of literary glory — at least Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus, and

Plato crossed the seas, exiles, in truth, rather than travellers, to instruct

themselves in this. Returning to their native land, they vaunted the claims of

magic and maintained its secret doctrine.... In the Latin nations there are

early traces of it, as, for instance, in our Laws of the Twelve Tables8

and other monuments, as I have said in a former book. In fact, it was not until

the year 657 after the foundation of Rome, under the consulate of Cornelius

Lentulus Crassus, that it was forbidden by a senatus consultum to

sacrifice human beings; a fact which proves that up to this date these horrible

sacrifices were made. The Gauls have been captivated by it, and that even down

to our own times, for it was the Emperor Tiberius who suppressed the Druids and

all the herd of prophets and medicine-men. But what is the use of launching

prohibitions against an art which has thus traversed the ocean and penetrated

even to the confines of Nature?” (Hist. Nat. xxx.) Pliny

adds that the first person whom he can ascertain to have written on this

subject was Osthanes, who accompanied Xerxes in his war against the Greeks, and

who propagated the “germs of his monstrous art” wherever he went in Europe. Magic

was not — so Pliny believed — indigenous either in Greece or in Italy, but was

so much at home in Britain and conducted with such elaborate ritual that Pliny

says it would almost seem as if it was they who had taught it to the Persians,

not the Persians to them. Traces of Magic in Megalithic

Monuments

The

imposing relics of their cult which the Megalithic People have left us are full

of indications of their religion. Take, for instance, the remarkable tumulus of

Mané-er-H’oeck, in Brittany. This monument was explored in 1864 by M. René

Galles, who describes it as absolutely intact — the surface of the earth

unbroken, and everything as the builders left it.9 At the entrance

to the rectangular chamber was a sculptured slab, on which was graven a

mysterious sign, perhaps the totem of a chief. Immediately on entering the

chamber was found a beautiful pendant in green jasper about the size of an egg.

On the floor in the centre of the chamber was a most singular arrangement,

consisting of a large ring of jadite, slightly oval in shape, with a

magnificent axe-head, also of jadite, its point resting on the ring. The axe

was a well-known symbol of power or godhead, and is frequently found in

rock-carvings of the Bronze Age, as well as in Egyptian hieroglyphs, Minoan

carvings, &c. At a little distance from these there lay two large pendants

of jasper, then an axe-head in white jade,10 then another jasper

pendant. All these objects were ranged with evident intention en suite,

forming a straight line which coincided exactly with one of the diagonals of

the chamber, running from north-west to south-east. In one of the corners of

the chamber were found 101 axe-heads in jade, jadite, and fibrolite. There were

no traces of bones or cinders, no funerary urn; the structure was a cenotaph.

“Are we not here,” asks Bertrand, “in presence of some ceremony relating to the

practices of magic?” Chiromancy at Gavr’inis

In connexion

with the great sepulchral monument of Gavr’inis a very curious observation was

made by M. Albert Maitre, an inspector of the Musée des Antiquités Nationales.

There were found here

— as commonly in other

megalithic monuments in Ireland and Scotland — a

number of stones sculptured with a singular and characteristic design in waving

and concentric lines. Now if the curious lines traced upon the human hand at the

roots and tips of the fingers be examined under a lens, it will be found that

they bear an exact resemblance to these designs of megalithic sculpture. One

seems almost like a cast of the other. These lines on the human hand are so

distinct and peculiar that, as is well known, they have been adopted as a

method of identification of criminals. Can this resemblance be the result of

chance? Nothing like these peculiar assemblages of sculptured lines has ever

been found except in connexion with these monuments. Have we not here a

reference to chiromancy — a magical art much practised in ancient and even in

modern times? The hand as a symbol of power was a well-known magical emblem,

and has entered largely even into Christian symbolism — note, for instance, the

great hand sculptured on the under side of one of the arms of the Cross of

Muiredach at Monasterboice.

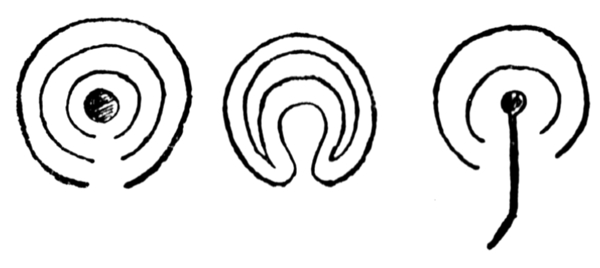

Stones from Brittany sculptured with Footprints, Axes, “Finger-markings,” &c. (Sergi) Holed Stones

Another singular and as yet unexplained

feature which appears in many of these monuments, from Western Europe to India,

is the presence of a small hole bored through one of the stones composing the

chamber. Was it an aperture intended for the spirit of the dead? or for

offerings to them? or the channel through which revelations from the

spirit-world were supposed to come to a priest or magician? or did it partake

of all these characters? Holed stones, not forming part of a dolmen, are, of

course, among the commonest relics of the ancient cult, and are still venerated

and used in practices connected with child-bearing, &c. Here we are doubtless to interpret the emblem

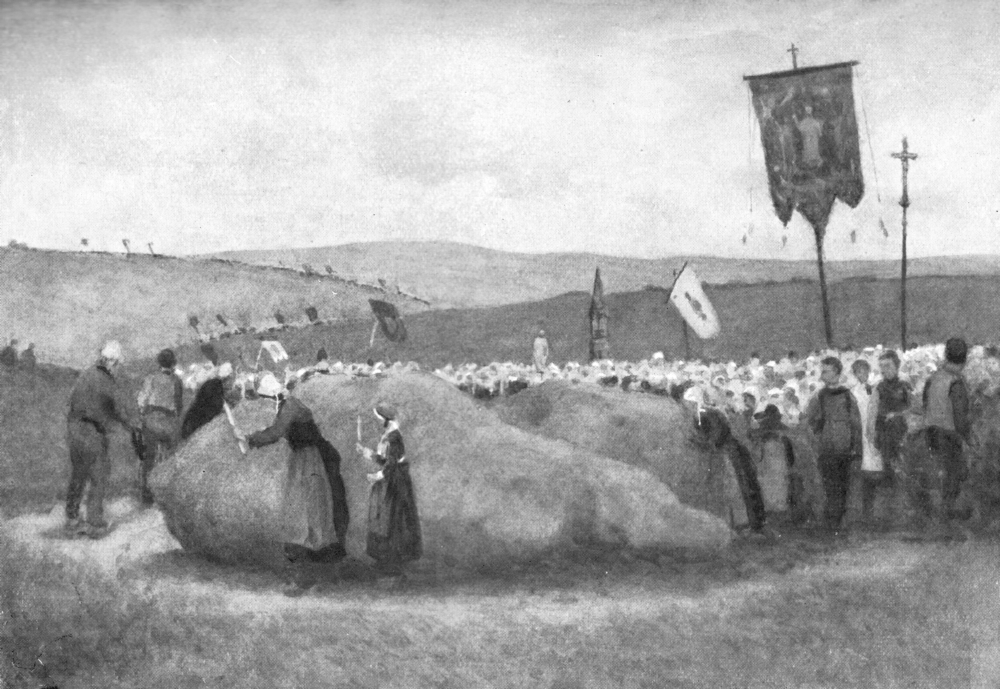

as a symbol of sex.  Dolmen at Trie, France (After Gailhabaud)  Dolmens in the Deccan, India (After Meadows-Taylor)  Modern Stone-worship at Locronan, Brittany Arthur G. Bell Stone-Worship

Besides

the heavenly bodies, we find that rivers, trees, mountains, and stones were all

objects of veneration among this primitive people. Stone-worship was

particularly common, and is not so easily explained as the worship directed

toward objects possessing movement and vitality. Possibly an explanation of the

veneration attaching to great and isolated masses of unhewn stone may be found

in their resemblance to the artificial dolmens and cromlechs.11 No

superstition has proved more enduring. In A.D. 452 we find the Synod of Arles

denouncing those who “venerate trees and wells and stones,” and the

denunciation was repeated by Charlemagne, and by numerous Synods and Councils

down to recent times. Yet a drawing, here reproduced, which was lately made on

the spot by Mr. Arthur Bell shows this very act of worship still in full force

in Brittany, and shows the symbols and the sacerdotal organisation of

Christianity actually pressed into the service of this immemorial paganism.

According to Mr. Bell, the clergy take part in these performances with much

reluctance, but are compelled to do so by the force of local opinion. Holy

wells, the water of which is supposed to cure diseases, are still very common

in Ireland, and the cult of the waters of Lourdes may, in spite of its adoption

by the Church, be mentioned as a notable case in point on the Continent. Cup-and-Ring Markings

Another singular emblem, upon the meaning of

which no light has yet been thrown, occurs frequently in connexion with

megalithic monuments. The accompanying illustrations show examples of it.

Cup-shaped hollows are made in the surface of the stone, these are often

surrounded with concentric rings, and from the cup one or more radial lines are

drawn to a point outside the circumference of the rings. Occasionally a system

of cups are joined by these lines, but more frequently they end a little way outside

the widest of the rings. These strange markings are found in Great Britain and

Ireland, in Brittany, and at various places in India, where they are called mahadéos.12

I have also found a curious example — for such it appears to be — in Dupaix’

“Monuments of New Spain.” It is reproduced in Lord Kingsborough’s “Antiquities

of Mexico,” vol. iv. On the circular top of a cylindrical stone, known as the

“Triumphal Stone,” is carved a central cup, with nine concentric circles round

it, and a duct or channel cut straight from the cup through all the circles to

the rim. Except that the design here is richly decorated and accurately drawn,

it closely resembles a typical European cup-and-ring marking. That these markings

mean something, and that, wherever they are found, they mean the same thing,

can hardly be doubted, but what that meaning is remains yet a puzzle to

antiquarians. The guess may perhaps be hazarded that they are diagrams or plans

of a megalithic sepulchre. The central hollow represents the actual

burial-place. The circles are the standing stones, fosses, and ramparts which

often surrounded it; and the line or duct drawn from the centre outwards

represents the subterranean approach to the sepulchre. The apparent “avenue”

intention of the duct is clearly brought out in the varieties given below,

which I take from Simpson. As the sepulchre was also a holy place or shrine,

the occurrence of a representation of it among other carvings of a sacred

character is natural enough; it would seem symbolically to indicate that the

place was holy ground. How far this suggestion might apply to the Mexican

example I am unable to say.  (After Sir J. Simpson)  Varieties of Cup-and-ring Markings One

of the most important and richly sculptured of European megalithic monuments is

the great chambered tumulus of New Grange, on the northern bank of the Boyne,

in Ireland. This tumulus, and the others which occur in its neighbourhood,

appear in ancient Irish mythical literature in two different characters, the

union of which is significant. They are regarded on the one hand as the

dwelling-places of the Sidhe (pronounced Shee), or Fairy Folk, who

represent, probably, the deities of the ancient Irish, and they are also,

traditionally, the burial-places of the Celtic High Kings of pagan Ireland. The

story of the burial of King Cormac, who was supposed to have heard of the

Christian faith long before it was actually preached in Ireland by St. Patrick

and who ordered that he should not be buried at the royal cemetery by the

Boyne, on account of its pagan associations, points to the view that this place

was the centre of a pagan cult involving more than merely the interment of

royal personages in its precincts. Unfortunately these monuments are not

intact; they were opened and plundered by the Danes in the ninth century,13

but enough evidence remains to show that they were sepulchral in their origin,

and were also associated with the cult of a primitive religion. The most

important of them, the tumulus of New Grange, has been thoroughly explored and described

by Mr. George Coffey, keeper of the collection of Celtic antiquities in the

National Museum, Dublin.14 It appears from the outside like a large

mound, or knoll, now overgrown with bushes. It measures about 280 feet across,

at its greatest diameter, and is about 44 feet in height. Outside it there runs

a wide circle of standing stones originally, it would seem, thirty-five in

number. Inside this circle is a ditch and rampart, and on top of this rampart

was laid a circular curb of great stones 8 to 10 feet long, laid on edge, and

confining what has proved to be a huge mound of loose stones, now overgrown, as

we have said, with grass and bushes. It is in the interior of this mound that

the interest of the monument lies. Towards the end of the seventeenth century some

workmen who were getting road-material from the mound came across the entrance

to a passage which led into the interior, and was marked by the fact that the

boundary stone below it is richly carved with spirals and lozenges. This

entrance faces exactly south-east. The passage is formed of upright slabs of

unhewn stone roofed with similar slabs, and varies from nearly 5 feet to 7 feet

10 inches in height; it is about 3 feet wide, and runs for 62 feet straight

into the heart of the mound. Here it ends in a cruciform chamber, 20 feet high,

the roof, a kind of dome, being formed of large flat stones, overlapping

inwards till they almost meet at the top, where a large flat stone covers all.

In each of the three recesses of the cruciform chamber there stands a large

stone basin, or rude sarcophagus, but not traces of any burial now remains. Symbolic Carvings at New Grange

The

stones are all raw and undressed, and were selected for their purpose from the

river-bed and elsewhere close by. On their flat surfaces, obtained by splitting

slabs from the original quarries, are found the carvings which form the unique

interest of this strange monument. Except for the large stone with spiral

carvings and one other at the entrance to the mound, the intention of these

sculptures does not appear to have been decorative, except in a very rude and

primitive sense. There is no attempt to cover a given surface with a system of

ornament appropriate to its size and shape. The designs are, as it were,

scribbled upon the walls anyhow and anywhere.15 Among them

everywhere the spiral is prominent. The resemblance of some of these carvings

to the supposed finger-markings of the stones at Gavr’inis is very remarkable.

Triple and double spiral are also found, as well as lozenges and zigzags. A

singular carving representing what looks like a palm-branch or fern-leaf is

found in the west recess. The drawing of this object is naturalistic, and it is

hard to interpret it, as Mr. Coffey is inclined to do, as merely a piece of so-called

“herring-bone” pattern.16 A similar palm-leaf design, but with the

ribs arranged at right angles to the central axis, is found in the neighbouring

tumulus of Dowth, at Loughcrew, and in combination with a solar emblem, the

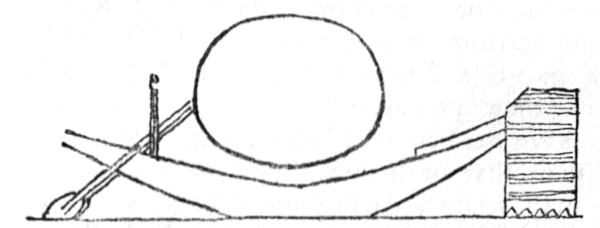

swastika, on a small altar in the Pyrenees, figured by Bertrand.  Photograph by R. Welch, Belfast The Ship Symbol at New Grange

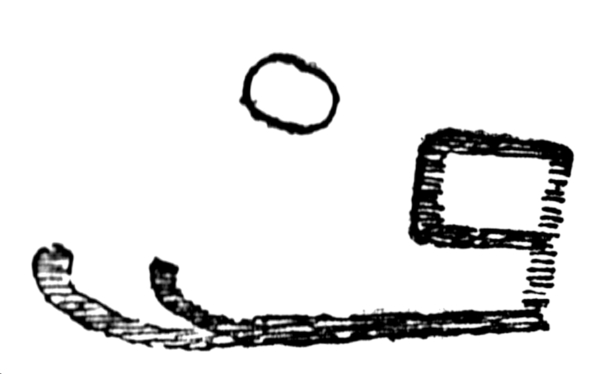

Another

remarkable and, as far as Ireland goes, unusual figure is found sculptured in

the west recess at New Grange. It has been interpreted by various critics as a

mason’s mark, a piece of Phoenician writing, a group of numerals, and finally

(and no doubt correctly) by Mr. George Coffey as a rude representation of a

ship with men on board and uplifted sail. It is noticeable that just above it

is a small circle, forming, apparently, part of the design. Another example

occurs at Dowth.  Solar Ship (with Sail?) from New Grange, Ireland The significance of this marking, as we shall

see, is possibly very great. It has been discovered that on certain stones in

the tumulus of Locmariaker, in Brittany,17 there occur a number of

very similar figures, one of them showing the circle in much the same relative

position as at New Grange. The axe, an Egyptian hieroglyph for godhead and a well-known

magical emblem, is also represented on this stone. Again, in a brochure by Dr.

Oscar Montelius on the rock-sculptures of Sweden18 we find a

reproduction (also given in Du Chaillu’s “Viking Age”) of a rude rock-carving

showing a number of ships with men on board, and the circle quartered by a

cross — unmistakably a solar emblem — just above one of them. That these ships

(which, like the Irish example, are often so summarily represented as to be

mere symbols which no one could identify as a ship were the clue not given by

other and more elaborate representations) were drawn so frequently in

conjunction with the solar disk merely for amusement or for a purely decorative

object seems to me most improbable. In the days of the megalithic folk a

sepulchral monument, the very focus of religious ideas, would hardly have been

covered with idle and meaningless scrawls. “Man,” as Sir J. Simpson has well

said, “has ever conjoined together things sacred and things sepulchral.” Nor do

these scrawls, in the majority of instances, show any glimmering of a

decorative intention. But if they had a symbolic intention, what is it that

they symbolise?

The Ship Symbol in Egypt

Now

this symbol of the ship, with or without the actual portrayal of the solar

emblem, is of very ancient and very common occurrence in the sepulchral art of

Egypt. It is connected with the worship of Rā, which came in fully 4000 years

B.C. Its meaning as an Egyptian symbol is well known. The ship was called the

Boat of the Sun. It was the vessel in which the Sun-god performed his journeys;

in particular, the journey which he made nightly to the shores of the

Other-world, bearing with him in his bark the souls of the beatified dead. The

Sun-god, Rā, is sometimes represented by a disk, sometimes by other emblems,

hovering above the vessel or contained within it. Any one who will look over

the painted or sculptured sarcophagi in the British Museum will find a host of

examples. Sometimes he will find representations of the life-giving rays of Rā pouring

down upon the boat and its occupants. Now, in one of the Swedish rock-carvings

of ships at Backa, Bohuslän, given by Montelius, a ship crowded with figures is

shown beneath a disk with three descending rays, and again another ship with a

two-rayed sun above it. It may be added that in the tumulus of Dowth, which is

close to that of New Grange and is entirely of the same character and period,

rayed figures and quartered circles, obviously solar emblems, occur abundantly,

as also at Loughcrew and other places in Ireland, and one other ship figure has

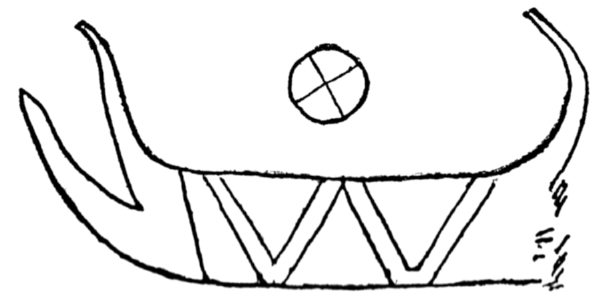

been identified at Dowth  Egyptian Solar Bark, XXII Dynasty (British Museum)  Egyptian Solar Bark, with god Khnemu and attendant deities (British Museum) In Egypt the solar boat is sometimes

represented as containing the solar emblem alone, sometimes it contains the

figure of a god with attendant deities, sometimes it contains a crowd of

passengers representing human souls, and sometimes the figure of a single

corpse on a bier. The megalithic carvings also sometimes show the solar emblem

and sometimes not; the boats are sometimes filled with figures and are

sometimes empty. When a symbol has once been accepted and understood, any

conventional or summary representation of it is sufficient. I take it that the

complete form of the megalithic symbol is that of a boat with figures in it and

with the solar emblem overhead. These figures, assuming the foregoing interpretation

of the design to be correct, must clearly be taken for representations of the

dead on their way to the Other-world. They cannot be deities, for

representations of the divine powers under human aspect were quite unknown to

the Megalithic People, even after the coming of the Celts — they first occur in

Gaul under Roman influence. But if these figures represent the dead, then we

have clearly before us the origin of the so-called “Celtic” doctrine of

immortality. The carvings in question are pre-Celtic. They are found where no

Celts ever penetrated. Yet they point to the existence of just that Other-world

doctrine which, from the time of Cæsar downwards, has been associated with

Celtic Druidism, and this doctrine was distinctively Egyptian.  Egyptian Bark, with figure of Rā holding an Ankh, enclosed in Solar Disk. XIX Dynasty (British Museum) The “Navetas”

In

connexion with this subject I may draw attention to the theory of Mr. W.C.

Borlase that the typical design of an Irish dolmen was intended to represent a

ship. In Minorca there are analogous structures, there popularly called navetas

(ships), so distinct is the resemblance. But, he adds, “long before the caves

and navetas of Minorca were known to me I had formed the opinion that

what I have so frequently spoken of as the ‘wedge-shape’ observable so

universally in the ground-plans of dolmens was due to an original conception of

a ship. From sepulchral tumuli in Scandinavia we know actual vessels have on

several occasions been disinterred. In cemeteries of the Iron Age, in the same

country, as well as on the more southern Baltic coasts, the ship was a

recognised form of sepulchral enclosure.”19 If Mr. Borlase’s view is

correct, we have here a very strong corroboration of the symbolic intention

which I attribute to the solar ship-carvings of the Megalithic People. The Ship Symbol in Babylonia

The

ship symbol, it may be remarked, can be traced to about 4000 B.C. in Babylonia,

where every deity had his own special ship (that of the god Sin was called the

Ship of Light), his image being carried in procession on a litter formed like a

ship. This is thought by Jastrow20 to have originated at a time when

the sacred cities of Babylonia were situated on the Persian Gulf, and when religious

processions were often carried out by water.

The Symbol of the Feet

Yet

there is reason to think that some of these symbols were earlier than any known

mythology, and were, so to say, mythologised differently by different peoples,

who got hold of them from this now unknown source. A remarkable instance is

that of the symbol of the Two Feet. In Egypt the Feet of Osiris formed one of

the portions into which his body was cut up, in the well-known myth. They were

a symbol of possession or of visitation. “I have come upon earth,” says the

“Book of the Dead” (ch. xvii.), “and with my two feet have taken possession, I

am Tmu.” Now this symbol of the feet or footprint is very widespread. It is

found in India, as the print of the foot of Buddha,21 it is found

sculptured on dolmens in Brittany,22 and it occurs in rock-carvings

in Scandinavia.23 In Ireland it passes for the footprints of St.

Patrick or St. Columba. Strangest of all, it is found unmistakably in Mexico.24

Tyler, in his “Primitive Culture” (ii. p. 197) refers to “the Aztec ceremony at

the Second Festival of the Sun God, Tezcatlipoca, when they sprinkled maize flour

before his sanctuary, and his high priest watched till he beheld the divine

footprints, and then shouted to announce, ‘Our Great God is come.’ ”  The Two Feet Symbol The Ankh on Megalithic

Carvings

There

is very strong evidence of the connexion of the Megalithic People with North

Africa. Thus, as Sergi points out, many signs (probably numerical) found on ivory

tablets in the cemetery at Naqada discovered by Flinders Petrie are to be met

with on European dolmens. Several later Egyptian hieroglyphic signs, including

the famous Ankh, or crux ansata, the symbol of vitality or

resurrection, are also found in megalithic carvings.25 From these

correspondences Letourneau drew the conclusion “that the builders of our

megalithic monuments came from the South, and were related to the races of

North Africa.”26  The Ankh Evidence from Language

Approaching

the subject from the linguistic side, Rhys and Brynmor Jones find that the

African origin — at least proximately — of the primitive population of Great

Britain and Ireland is strongly suggested. It is here shown that the Celtic

languages preserve in their syntax the Hamitic, and especially the Egyptian

type.27 Egyptian and “Celtic” Ideas of

Immortality

The

facts at present known do not, I think, justify us in framing any theory as to

the actual historical relation of the dolmen-builders of Western Europe with

the people who created the wonderful religion and civilisation of ancient

Egypt. But when we consider all the lines of evidence that converge in this

direction it seems clear that there was such a relation. Egypt was the classic

land of religious symbolism. It gave to Europe the most beautiful and most

popular of all its religious symbols, that of the divine mother and child.26

I believe that it also gave to the primitive inhabitants of Western Europe the

profound symbol of the voyaging spirits guided to the world of the dead by the

God of Light. The

religion of Egypt, above that of any people whose ideas we know to have been

developed in times so ancient, centred on the doctrine of a future life. The

palatial and stupendous tombs, the elaborate ritual, the imposing mythology,

the immense exaltation of the priestly caste, all these features of Egyptian

culture were intimately connected with their doctrine of the immortality of the

soul. To

the Egyptian the disembodied soul was no shadowy simulacrum, as the classical

nations believed — the future life was a mere prolongation of the present; the

just man, when he had won his place in it, found himself among his relatives,

his friends, his workpeople, with tasks and enjoyments very much like those of

earth. The doom of the wicked was annihilation; he fell a victim to the

invisible monster called the Eater of the Dead.

Now

when the classical nations first began to take an interest in the ideas of the

Celts the thing that principally struck them was the Celtic belief in

immortality, which the Gauls said was “handed down by the Druids.” The

classical nations believed in immortality; but what a picture does Homer, the

Bible of the Greeks, give of the lost, degraded, dehumanised creatures which

represented the departed souls of men! Take, as one example, the description of

the spirits of the suitors slain by Odysseus as Hermes conducts them to the

Underworld: “Now were summoned the souls of the

dead by Cyllenian Hermes.... Touched by the wand they awoke, and

obeyed him and followed him, squealing, Even as bats in the dark, mysterious

depths of a cavern Squeal as they flutter around,

should one from the cluster be fallen Where from the rock suspended they

hung, all clinging together; So did the souls flock squealing

behind him, as Hermes the Helper Guided them down to the gloom

through dank and mouldering pathways.”28 The

classical writers felt rightly that the Celtic idea of immortality was something

altogether different from this. It was both loftier and more realistic; it

implied a true persistence of the living man, as he was at present, in all his

human relations. They noted with surprise that the Celt would lend money on a

promissory note for repayment in the next world.29 That is an

absolutely Egyptian conception. And this very analogy occurred to Diodorus in

writing of the Celtic idea of immortality — it was like nothing that he knew of

out of Egypt.30 The Doctrine of Transmigration

Many

ancient writers assert that the Celtic idea of immortality embodied the

Oriental conception of the transmigration of souls, and to account for this the

hypothesis was invented that they had learned the doctrine from Pythagoras, who

represented it in classical antiquity. Thus Cæsar: “The principal point of

their [the Druids’] teaching is that the soul does not perish, and that after

death it passes from one body into another.” And Diodorus: “Among them the

doctrine of Pythagoras prevails, according to which the souls of men are

immortal, and after a fixed term recommence to live, taking upon themselves a

new body.” Now traces of this doctrine certainly do appear in Irish legend.

Thus the Irish chieftain, Mongan, who is an historical personage, and whose

death is recorded about A.D. 625, is said to have made a wager as to the place

of death of a king named Fothad, slain in a battle with the mythical hero Finn

mac Cumhal in the third century. He proves his case by summoning to his aid a revenant

from the Other-world, Keelta, who was the actual slayer of Fothad, and who describes

correctly where the tomb is to be found and what were its contents. He begins

his tale by saying to Mongan, “We were with thee,” and then, turning to the

assembly, he continues: “We were with Finn, coming from Alba....” “Hush,” says

Mongan, “it is wrong of thee to reveal a secret.” The secret is, of course,

that Mongan was a reincarnation of Finn.31 But the evidence on the

whole shows that the Celts did not hold this doctrine at all in the same way as

Pythagoras and the Orientals did. Transmigration was not, with them, part of

the order of things. It might happen, but in general it did not; the new

body assumed by the dead clothed them in another, not in this world, and so far

as we can learn from any ancient authority, there does not appear to have been

any idea of moral retribution connected with this form of the future life. It

was not so much an article of faith as an idea which haunted the imagination,

and which, as Mongan’s caution indicates, ought not to be brought into clear light. However

it may have been conceived, it is certain that the belief in immortality was

the basis of Celtic Druidism.33 Caesar affirms this distinctly, and

declares the doctrine to have been fostered by the Druids rather for the

promotion of courage than for purely religious reasons. An intense Other-world

faith, such as that held by the Celts, is certainly one of the mightiest of

agencies in the hands of a priesthood who hold the keys of that world. Now

Druidism existed in the British Islands, in Gaul, and, in fact, so far as we

know, wherever there was a Celtic race amid a population of dolmen-builders.

There were Celts in Cisalpine Gaul, but there were no dolmens there, and there

were no Druids.34 What is quite clear is that when the Celts got to

Western Europe they found there a people with a powerful priesthood, a ritual,

and imposing religious monuments; a people steeped in magic and mysticism and

the cult of the Underworld. The inferences, as I read the facts, seem to be

that Druidism in its essential features was imposed upon the imaginative and

sensitive nature of the Celt — the Celt with his “extraordinary aptitude” for

picking up ideas — by the earlier population of Western Europe, the Megalithic People,

while, as held by these, it stands in some historical relation, which I am not

able to pursue in further detail, with the religious culture of ancient Egypt.

Much obscurity still broods over the question, and perhaps will always do so,

but if these suggestions have anything in them, then the Megalithic People have

been brought a step or two out of the atmosphere of uncanny mystery which has

surrounded them, and they are shown to have played a very important part in the

religious development of Western Europe, and in preparing that part of the

world for the rapid extension of the special type of Christianity which took

place in it. Bertrand, in his most interesting chapter on “L’Irlande Celtique,”35

points out that very soon after the conversion of Ireland to Christianity, we

find the country covered with monasteries, whose complete organisation seems to

indicate that they were really Druidic colleges transformed en masse.

Cæsar has told us what these colleges were like in Gaul. They were very numerous.

In spite of the severe study and discipline involved, crowds flocked into them

for the sake of the power wielded by the Druidic order, and the civil

immunities which its members of all grades enjoyed. Arts and sciences were

studied there, and thousands of verses enshrining the teachings of Druidism

were committed to memory. All this is very like what we know of Irish Druidism.

Such an organisation would pass into Christianity of the type established in

Ireland with very little difficulty. The belief in magical rites would survive

— early Irish Christianity, as its copious hagiography plainly shows, was as

steeped in magical ideas as ever was Druidic paganism. The belief in

immortality would remain, as before, the cardinal doctrine of religion. Above

all the supremacy of the sacerdotal order over the temporal power would remain unimpaired;

it would still be true, as Dion Chrysostom said of the Druids, that “it is they

who command, and kings on thrones of gold, dwelling in splendid palaces, are

but their ministers, and the servants of their thought.”36 Cæsar on the Druidic Culture

The

religious, philosophic, and scientific culture superintended by the Druids is

spoken of by Cæsar with much respect. “They discuss and impart to the youth,”

he writes, “many things respecting the stars and their motions, respecting the

extent of the universe and of our earth, respecting the nature of things,

respecting the power and the majesty of the immortal gods” (bk. vi. 14). We

would give much to know some particulars of the teaching here described. But

the Druids, though well acquainted with letters, strictly forbade the committal

of their doctrines to writing; an extremely sagacious provision, for not only

did they thus surround their teaching with that atmosphere of mystery which

exercises so potent a spell over the human mind, but they ensured that it could

never be effectively controverted. Human Sacrifices in Gaul

In

strange discord, however, with the lofty words of Cæsar stands the abominable

practice of human sacrifice whose prevalence he noted among the Celts.

Prisoners and criminals, or if these failed even innocent victims, probably

children, were encased, numbers at a time, in huge frames of wickerwork, and

there burned alive to win the favour of the gods. The practice of human

sacrifice is, of course, not specially Druidic — it is found in all parts both

of the Old and of the New World at a certain stage of culture, and was

doubtless a survival from the time of the Megalithic People. The fact that it

should have continued in Celtic lands after an otherwise fairly high state of

civilisation and religious culture had been attained can be paralleled from Mexico

and Carthage, and in both cases is due, no doubt, to the uncontrolled dominance

of a priestly caste.  Human Sacrifices in Gaul Human Sacrifices in Ireland

Bertrand

endeavours to dissociate the Druids from these practices, of which he says

strangely there is “no trace” in Ireland, although there, as elsewhere in

Celtica, Druidism was all-powerful. There is little doubt, however, that in

Ireland also human sacrifices at one time prevailed. In a very ancient tract,

the “Dinnsenchus,” preserved in the “Book of Leinster,” it is stated that on Moyslaught,

“the Plain of Adoration,” there stood a great gold idol, Crom Cruach (the

Bloody Crescent). To it the Gaels used to sacrifice children when praying for

fair weather and fertility — “it was milk and corn they asked from it in

exchange for their children — how great was their horror and their moaning!”37 And in Egypt

In

Egypt, where the national character was markedly easy-going, pleasure-loving,

and little capable of fanatical exaltation, we find no record of any such cruel

rites in the monumental inscriptions and paintings, copious as is the

information which they give us on all features of the national life and

religion.38 Manetho, indeed, the Egyptian historian who wrote in the

third century B.C., tells us that human sacrifices were abolished by Amasis I.

so late as the beginning of the XVIII Dynasty — about 1600 B.C. But the

complete silence of the other records shows us that even if we are to believe

Manetho, the practice must in historic times have been very rare, and must have

been looked on with repugnance. The Names of Celtic Deities

What

were the names and the attributes of the Celtic deities? Here we are very much

in the dark. The Megalithic People did not imagine their deities under concrete

personal form. Stones, rivers, wells, trees, and other natural objects were to

them the adequate symbols, or were half symbols, half actual embodiments, of

the supernatural forces which they venerated. But the imaginative mind of the

Aryan Celt was not content with this. The existence of personal gods with

distinct titles and attributes is reported to us by Caesar, who equates them

with various figures in the Roman pantheon — Mercury, Apollo, Mars, and so

forth. Lucan mentions a triad of deities, Æsus, Teutates, and Taranus;39

and it is noteworthy that in these names we seem to be in presence of a true

Celtic, i.e., Aryan, tradition. Thus Æsus is derived by Belloguet from

the Aryan root as, meaning “to be”, which furnished the name of

Asura-masda (l’Esprit Sage) to the Persians, Æsun to the Umbrians, Asa

(Divine Being) to the Scandinavians. Teutates comes from a Celtic root meaning

“valiant”, “warlike”, and indicates a deity equivalent to Mars. Taranus (?

Thor), according to de Jubainville, is a god of the Lightning (taran in

Welsh, Cornish, and Breton is the word for “thunderbolt”). Votive inscriptions

to these gods have been found in Gaul and Britain. Other inscriptions and sculptures

bear testimony to the existence in Gaul of a host of minor and local deities

who are mostly mere names, or not even names, to us now. In the form in which

we have them these conceptions bear clear traces of Roman influence. The

sculptures are rude copies of the Roman style of religious art. But we meet

among them figures of much wilder and stranger aspect — gods with triple faces,

gods with branching antlers on their brows, ram-headed serpents, and other now

unintelligible symbols of the older faith. Very notable is the frequent

occurrence of the cross-legged “Buddha” attitude so prevalent in the religious

art of the East and of Mexico, and also the tendency, so well known in Egypt,

to group the gods in triads. Caesar on the Celtic Deities

Caesar,

who tries to fit the Gallic religion into the framework of Roman mythology — which

was exactly what the Gauls themselves did after the conquest — says they held

Mercury to be the chief of the gods, and looked upon him as the inventor of all

the arts, as the presiding deity of commerce, and as the guardian of roads and

guide of travellers. One may conjecture that he was particularly, to the Gauls

as to the Romans, the guide of the dead, of travellers to the Other-world, Many

bronze statues to Mercury, of Gaulish origin, still remain, the name being

adopted by the Gauls, as many place-names still testify.40 Apollo

was regarded as the deity of medicine and healing, Minerva was the initiator of

arts and crafts, Jupiter governed the sky, and Mars presided over war. Cæsar is

here, no doubt, classifying under five types and by Roman names a large number

of Gallic divinities. The God of the Underworld

According

to Cæsar, a most notable deity of the Gauls was Roman nomenclature) Dis, or

Pluto, the god of the Underworld inhabited by the dead. From him all the Gauls

claimed to be descended, and on this account, says Cæsar, they began their

reckoning of the twenty-four hours of the day with the oncoming of night.41

The name of this deity is not given. D’Arbois de Jubainville considers that,

together with Æsus, Teutates, Taranus, and, in Irish mythology, Balor and the

Fomorians, he represents the powers of darkness, death, and evil, and Celtic

mythology is thus interpreted as a variant of the universal solar myth,

embodying the conception of the eternal conflict between Day and Night. The God of Light

The God

of Light appears in Gaul and in Ireland as Lugh, or Lugus, who has left his

traces in many place-names such as Lug-dunum (Leyden), Lyons, &c.

Lugh appears in Irish legend with distinctly solar attributes. When he meets

his army before the great conflict with the Fomorians, they feel, says the

saga, as if they beheld the rising of the sun. Yet he is also, as we shall see,

a god of the Underworld, belonging on the side of his mother Ethlinn, daughter

of Balor, to the Powers of Darkness. The Celtic Conception of Death

The

fact is that the Celtic conception of the realm of death differed altogether

from that of the Greeks and Romans, and, as I have already pointed out,

resembled that of Egyptian religion. The Other-world was not a place of gloom and

suffering, but of light and liberation. The Sun was as much the god of that

world as he was or this. Evil, pain, and gloom there were, no doubt, and no

doubt these principles were embodied by the Irish Celts in their myths of Balor

and the Fomorians, of which we shall hear anon; but that they were particularly

associated with the idea of death is, I think, a false supposition founded on

misleading analogies drawn from the ideas of the classical nations. Here the

Celts followed North African or Asiatic conceptions rather than those of the

Aryans of Europe. It is only by realising that the Celts as we know them in

history, from the break-up of the Mid-European Celtic empire onwards, formed a singular

blend of Aryan with non-Aryan characteristics, that we shall arrive at a true

understanding of their contribution to European history and their influence in

European culture. The Five Factors in Ancient Celtic

Culture

To

sum up the conclusions indicated: we can, I think, distinguish five distinct

factors in the religious and intellectual culture of Celtic lands as we find

them prior to the influx of classical or of Christian influences. First, we

have before us a mass of popular superstitions and of magical observances,

including human sacrifice. These varied more or less from place to place,

centring as they did largely on local features which were regarded as

embodiments or vehicles of divine or of diabolic power. Secondly, there was

certainly in existence a thoughtful and philosophic creed, having as its

central object of worship the Sun, as an emblem of divine power and constancy,

and as its central doctrine the immortality of the soul. Thirdly, there was a

worship of personified deities, Æsus, Teutates, Lugh, and others, conceived as

representing natural forces, or as guardians of social laws. Fourthly, the

Romans were deeply impressed with the existence among the Druids of a body of

teaching of a quasi-scientific nature about natural phenomena and the

constitution of the universe, of the details of which we unfortunately know

practically nothing. Lastly, we have to note the prevalence of a sacerdotal organisation,

which administered the whole system of religious and of secular learning and

literature,42 which carefully confined this learning to a privileged

caste, and which, by virtue of its intellectual supremacy and of the atmosphere

of religious awe with which it was surrounded, became the sovran power, social,

political, and religious, in every Celtic country. I have spoken of these

elements as distinct, and we can, indeed, distinguish them in thought, but in

practice they were inextricably intertwined, and the Druidic organisation

pervaded and ordered all. Can we now, it may be asked, distinguish among them

what is of Celtic and what of pre-Celtic and probably non-Aryan origin? This is

a more difficult task; yet, looking at all the analogies and probabilities, I

think we shall not be far wrong in assigning to the Megalithic People the

special doctrines, the ritual, and the sacerdotal organisation of Druidism, and

to the Celtic element the personified deities, with the zest for learning and

for speculation; while the popular superstitions were merely the local form

assumed by conceptions as widespread as the human race. The Celts of To-day

In

view of the undeniably mixed character of the populations called “Celtic” at

the present day, it is often urged that this designation has no real relation

to any ethnological fact. The Celts who fought with Caesar in Gaul and with the

English in Ireland are, it is said, no more — they have perished on a thousand

battlefields from Alesia to the Boyne, and an older racial stratum has come to

the surface in their place. The true Celts, according to this view, are only to

be found in the tall, ruddy Highlanders of Perthshire and North-west Scotland,

and in a few families of the old ruling race still surviving in Ireland and in

Wales. In all this I think it must be admitted that there is a large measure of

truth. Yet it must not be forgotten that the descendants of the Megalithic People

at the present day are, on the physical side, deeply impregnated with Celtic

blood, and on the spiritual with Celtic traditions and ideals. Nor, again, in

discussing these questions of race-character and its origin, must it ever be

assumed that the character of a people can be analysed as one analyses a

chemical compound, fixing once for all its constituent parts and determining

its future behaviour and destiny. Race-character, potent and enduring though it

be, is not a dead thing, cast in an iron mould, and thereafter incapable of

change and growth. It is part of the living forces of the world; it is plastic

and vital; it has hidden potencies which a variety of causes, such as a felicitous

cross with a different, but not too different, stock, or — in another sphere — the

adoption of a new religious or social ideal, may at any time unlock and bring

into action. Of

one thing I personally feel convinced — that the problem of the ethical, social,

and intellectual development of the people constituting what is called the

“Celtic Fringe” in Europe ought to be worked for on Celtic lines; by the

maintenance of the Celtic tradition, Celtic literature, Celtic speech — the

encouragement, in short, of all those Celtic affinities of which this mixed

race is now the sole conscious inheritor and guardian. To these it will

respond, by these it can be deeply moved; nor has the harvest ever failed those

who with courage and faith have driven their plough into this rich field. On

the other hand, if this work is to be done with success it must be done in no

pedantic, narrow, intolerant spirit; there must be no clinging to the outward

forms of the past simply because the Celtic spirit once found utterance in them.

Let it be remembered that in the early Middle Ages Celts from Ireland were the

most notable explorers, the most notable pioneers of religion, science, and

speculative thought in Europe.43 Modern investigators have traced

their footprints of light over half the heathen continent, and the schools of

Ireland were thronged with foreign pupils who could get learning nowhere else.

The Celtic spirit was then playing its true part in the world-drama, and a greater

it has never played. The legacy of these men should be cherished indeed, but

not as a museum curiosity; nothing could be more opposed to their free, bold,

adventurous spirit than to let that legacy petrify in the hands of those who

claim the heirship or their name and fame.

The Mythical Literature

After

the sketch contained in this and the foregoing chapter of the early history of

the Celts, and of the forces which have moulded it, we shall now turn to give

an account of the mythical and legendary literature in which their spirit most

truly lives and shines. We shall not here concern ourselves with any literature

which is not Celtic. With all that other peoples have made — as in the

Arthurian legends — of myths and tales originally Celtic, we have here nothing

to do. No one can now tell how much is Celtic in them and how much is not. And

in matters of this kind it is generally the final recasting that is of real

importance and value. Whatever we give, then, we give without addition or

reshaping. Stories, of course, have often to be summarised, but there shall be

nothing in them that did not come direct from the Celtic mind, and that does

not exist to-day in some variety, Gaelic or Cymric, of the Celtic tongue. 2 See p. 78. 3 See Borlase’s “Dolmens of Ireland,” pp. 605, 606, for a

discussion of this question. 4 Professor Ridgeway (see Report of the Brit. Assoc. for

1908) has contended that the Megalithic

People spoke an Aryan language;

otherwise he thinks more traces of its influence must have survived in the Celtic which supplanted it. The weight

of authority, as well as such direct

evidence as we possess, seems to be against his view. 5 See Holder,“Altceltischer Sprachschatz.” sulb voce

“Hyperboreoi.” 6 Thus the Greek pharmakon = medicine, poison, or

charm; and I am informed that the Central African word for magic or charm is mankwala,

which also means medicine. 7 If Pliny meant that it was here first codified and

organised he may be right, but the conceptions on which magic rest are

practically universal, and of immemorial antiquity. 8 Adopted 451 B.C. Livy entitles them “the fountain of all

public and private right.” They stood in

the Forum till the third century A.D.,

but have now perished, except for fragments preserved in various commentaries. 9 See “Revue Archeologique,” t. xii., 1865, “Fouilles de René

Galles.” 10 Jade is not found in the native state in Europe, nor nearer

than China. 11 Small stones, crystals, and gems were, however, also

venerated. The celebrated Black Stone of

Pergamos was the subject of an embassy from Rome to that city in the time of

the Second Punic War, the Sibylline

Books having predicted victory to its possessors. It was brought to Rome with great rejoicings in the

year 205. It is stated to have been

about the size of a man’s fist, and was probably a meteorite. Compare the myth in Hesiod which

relates how Kronos devoured a stone in

the belief that it was his offspring, Zeus. It

was then possible to mistake a stone for a god. 12 See Sir J. Simpson’s “Archaic Sculpturings” 1867. 13 The fact is recorded in the “Annals of the Four Masters”

Under the date 861, and in the “Annals

of Ulster” under 862. 14 See “Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy,” vol. xxx.

pt. i., 1892, and “New Grange,” by G.

Coffey, 1912. 15 It must be observed, however, that the decoration was,

certainly, in some, and perhaps in all

cases, carried out before the stones were

placed in position. This is also the case at Gavr’inis. 16 He has modified this view in his latest work, “New Grange,”

1912. 17 “Proc. Royal Irish Acad.,” vol. viii. 1863, p. 400, and G.

Coffey, op. cit. p. 30. 18 “Les Sculptures de Rochers de la Suède,” read at the

Prehistoric Congress, Stockholm, 1874;

and see G. Coffey, op. cit. p. 60. 19 “Dolmens of Ireland,” pp. 701-704. 20 “The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria.” 21 A good example from Amaravati (after Fergusson) is given

by Bertrand, “Rel. des G.,” p. 389. 22 Sergi, “The Mediterranean Race,” p. 313. 23 At Lökeberget, Bohuslän; see Monteiius, op. cit. 24 See Lord Kingsborough’s “Antiquities of Mexico,” passim,

and the Humboldt fragment of Mexican painting (reproduced in Churchward’s

“Signs and Symbols of Primordial Man”). 25 See Sergi, op. cit.

p. 290, for the Ankh on a French dolmen. 26 “Bulletin de la Soc. d’Anthropologie,” Paris, April 1893. 27 “The Welsh People,” pp. 616-664, where the subject is fully

discussed in an appendix by Professor J. Morris Jones. “The pre-Aryan idioms

which still live in Welsh and Irish were derived from a language allied to

Egyptian and the Berber tongues.” 28 Flinders Petrie, “Egypt and Israel,” pp. 137, 899. 29 I quote from Mr. H.B. Cotterill’s beautiful hexameter

version. 30 Valerius Maximus (about A.D 30) and other classical writers

mention this practice. 31 Book V. 32 De Jubainville, “Irish Mythological Cycle,” p.191 sqq.

33 The etymology of the word “Druid” is no longer an unsolved

problem. It had been suggested that the latter part of the word might be

connected with the Aryan root VID, which appears in “wisdom,” in the Latin videre,

&c., Thurneysen has now shown that this root in combination with the

intensive particle dru would yield the word dru-vids, represented

in Gaelic by draoi, a Druid, just as another intensive, su, with vids

yields the Gaelic saoi, a sage. 34 See Rice Holmes, “Cæsar’s Conquest,” p. 15, and pp. 532-536.

Rhys, it may be observed, believes that Druidism was the religion of the

aboriginal inhabitants of Western Europe “from the Baltic to Gibraltar”

(“Celtic Britain,” p. 73). But we only know of it where Celts and

dolmen-builders combined. Cæsar remarks of the Germans that they had no Druids

and cared little about sacrificial ceremonies. 35 “Rel. des Gaulois,” leçon xx. 36 Quoted by Bertrand, op.

cit. p. 279. 37 “The Irish Mythological Cycle,” by d’Arbois de Jubainville,

p. 6l. The “Dinnsenchus” in question is an early Christian document. No trace

of a being like Crom Cruach has been found as yet in the pagan literature of

Ireland, nor in the writings of St. Patrick, and I think it is quite probable

that even in the time of St. Patrick human sacrifices had become only a memory.

38 A representation of human sacrifice has, however, lately

been discovered in a Temple of the Sun

in the ancient Ethiopian capital, Meroë.

39 “You [Celts] who by cruel blood outpoured think to appease

the pitiless Teutates, the horrid Æsus

with his barbarous altars, and Taranus

whose worship is no gentler than that of the Scythian Diana”, to whom captive were offered up.

(Lucan, “Pharsalia”, i. 444.) An altar dedicated to Æsus has been discovered in

Paris. 40 Mont Mercure, Mercœur, Mercoirey, Montmartre (Mons Mercurii),

&c. 41 To this day in many parts of France the peasantry use terms

like annuit, o’né, anneue, &c., all meaning “to-night,” for aujourd’hui (Bertrand, “Rel. des G.,”

p. 356). 42 The fili, or professional poets, it must be

remembered, were a branch of the Druidic order. 43 For instance, Pelagius in the fifth century; Columba,

Columbanus, and St. Gall in the sixth; Fridolin, named Viator, “the

Traveller,” and Fursa in the seventh; Virgilius (Feargal) of Salzburg, who had to answer at Rome for

teaching the sphericity of the earth, in the eighth; Dicuil, “the Geographer,”

and Johannes Scotus Erigena — the master mind of his epoch — in the ninth. |