CHAPTER III.

KILLARNEY AND ABOUT THERE

KILLARNEY is a

considerable town, rather prim and staid and too offensively well

kept to be wholly appealing. It is by no means handsome of itself,

nor are its public buildings.

The chief industry is

catering, in one form or another, to the largely increasing number of

tourists who are constantly flocking thither.

The value of Killarney,

as a name of sentimental and romantic interest, lies in its

association with its lakes and the abounding wealth of natural

beauties around about it.

Torc Mountain and

waterfall, Muckross, Cloghereen, the Gap of Dunloe and its castle,

the upper, middle, and lower lakes, Purple Mountain, Black Valley,

Eagle’s Nest, and Innisfallen are all names with which to call up

ever living memories of the fairies of legend and folk-lore, and of

the more real personages of history and romance.

KILLARNEY AND ABOUT THERE

To recount them all, or

even to categorically enumerate them, would be impossible here.

There is but one way to

encompass them in a manner at all satisfactory, and that is to make

Killarney a centre, and radiate one’s journeys therefrom for as

extended a period as circumstances will allow. The guide-books set

forth the attractions and the ways and means in the usual

conventional manner, but it is useless to expect any real help from

them.

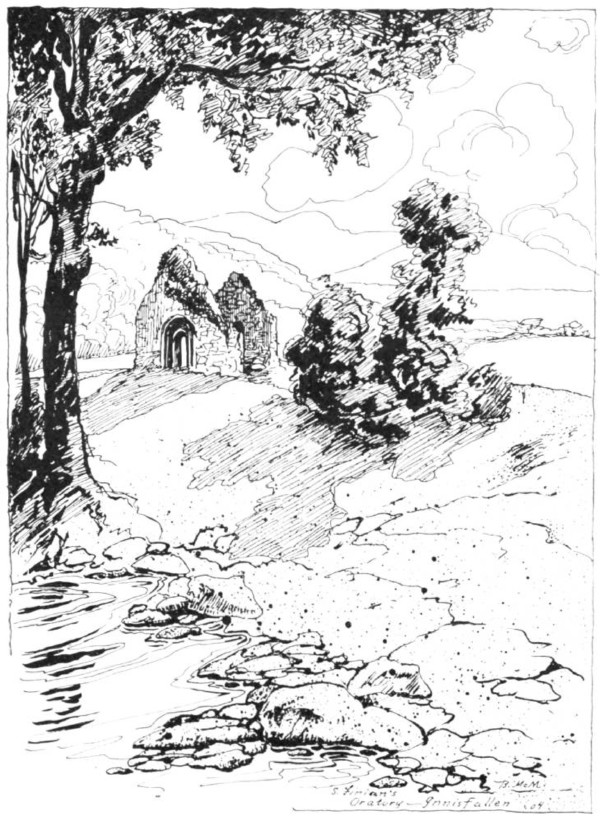

The true gem of

Killarney’s many charms is without question Lough Leane and

Innisfallen (Monk’s Robe Island), which lies embosomed in the lower

lake.

Yeats, the Irish poet,

spent the full force of his lyric genius in the verses which he wrote

with this entrancing isle for their motive.

Robert Louis Stevenson is

reported to have said that, of all modern poets, none has struck the

responsive chord of imagination as did this sweet singer with the

following lines: “And I shall have some

peace there,

For peace comes dropping

slow,

Dropping from the veils

of the morning

To where the cricket

sings;

There midnight’s all a

glimmer

And noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the

linnet’s wings.

“I will arise and go

now,

For always, night or day,

I hear lake water

lapping,

With low sounds by the

shore;

While I stand on the

roadway,

Or on the pavements gray,

I hear it in the deep

heart’s core.”

ST. FINIAN’S ORATORY,

INNISFALLEN.

Moore’s description is

perhaps as appropriate, but it is no more beautiful:

“Sweet Innisfallen,

fare thee well,

May calm and sunshine

long be thine!

How fair thou art let

others tell, —

To feel how fair shall

long be mine.”

From Glengarriff to

Killarney via

Kenmare is a long-drawn sweetness of prospect, which it is perhaps

impossible to duplicate for its sentimental charm, — an ability to

appreciate which belongs to us all, even if only to a limited extent.

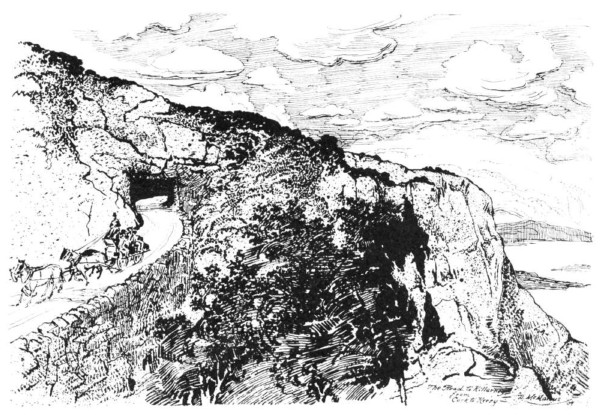

The road from County Cork

to County Kerry — and one journeys only by road from Bantry Bay to

Dingle Bay, via

Kenmare and Killarney, the age of steam not yet having arrived at

these parts — winds fascinatingly up and down hill and dale, diving

suddenly through a tunnelled rock, when a transformation takes place,

and one leaves the ruggedness and freshness of Bantry Bay for the

more or less humid fairy-land of the region about Killarney. The view

ahead is peculiarly grand in its contrast with that left behind. Down

the beetling precipices along which the road is clinging to its

sterile sides, one traces the valley beneath until it blends with the

silvery surface of Kenmare River. From Kenmare, the way to Killarney

is by the “Windy Gap.” Beneath lies an extensive valley, and

beyond is the Black Valley. Farther on are the skylines of the

mountains which encompass the wild and dark Gap of Dunloe; and,

farther still, will be observed the more jagged outlines of

“MacGillicuddy’s Reeks.” Soon one beholds the first view of the

beauties of far-famed Killarney, the immense valley in which repose

the three lakes, — the upper, lower, and middle, with their

numerous islets. En

route

from Kenmare to Killarney, one first comes to Muckross Abbey and

Demesne, of which Sir Walter Scott has said: “Art could make

another Versailles; it could not make another Muckross.” This is

characteristic of Sir Walter and his fine sentiment; but, as Muckross

is suggestive of nothing ever heard or thought of at Versailles, the

comparison is truly odious.

ON THE ROAD FROM CORK TO

KERRY.

Muckross is charming. It

is thoroughly Irish; and reeks of the native soil and its people,

wherein is its value to the traveller.

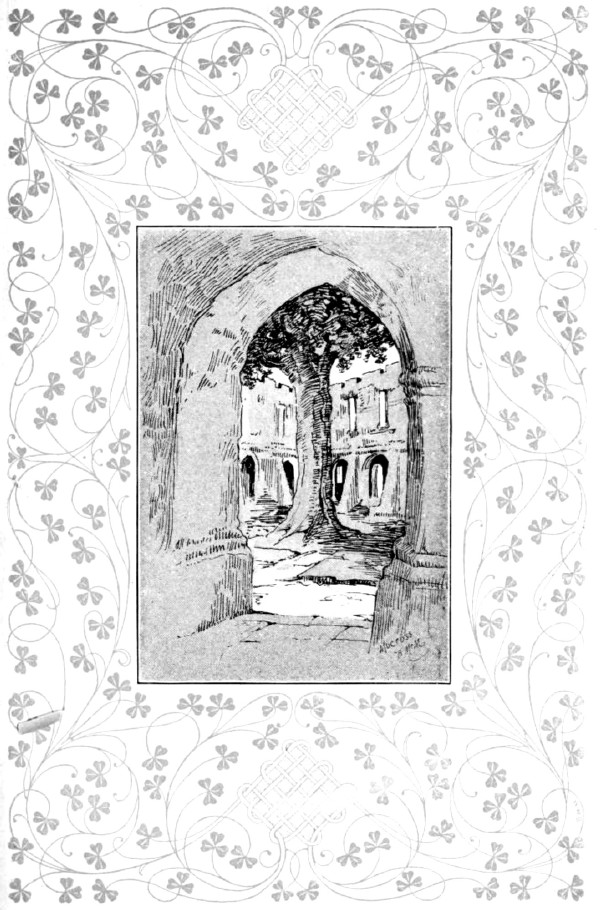

The scenery around about

Muckross is very beautiful, but its ruined abbey is the great

architectural relic of all Ireland. The ruins consist of the abbey

and church, which was founded for the Order of Franciscans by

McCarthy Mor, Prince of Desmond, in 1340, on the site of an old

church which, in 1192, had been destroyed by fire. The remains of

several of this prince’s descendants are said to rest here. In the

choir is the vault of the ancient Irish sept., the McCarthys, the

memory of whom is preserved by a rude sculptured monument. Here also

rest the remains of the Irish chieftains or princes of the houses of

O’Sullivan Mor and the O’Donoghue. The great beauty of these

ruins lies in its gloomy cloisters, which are rendered still more

gloomy by the close proximity of a magnificent yew-tree of immense

size and bulk.

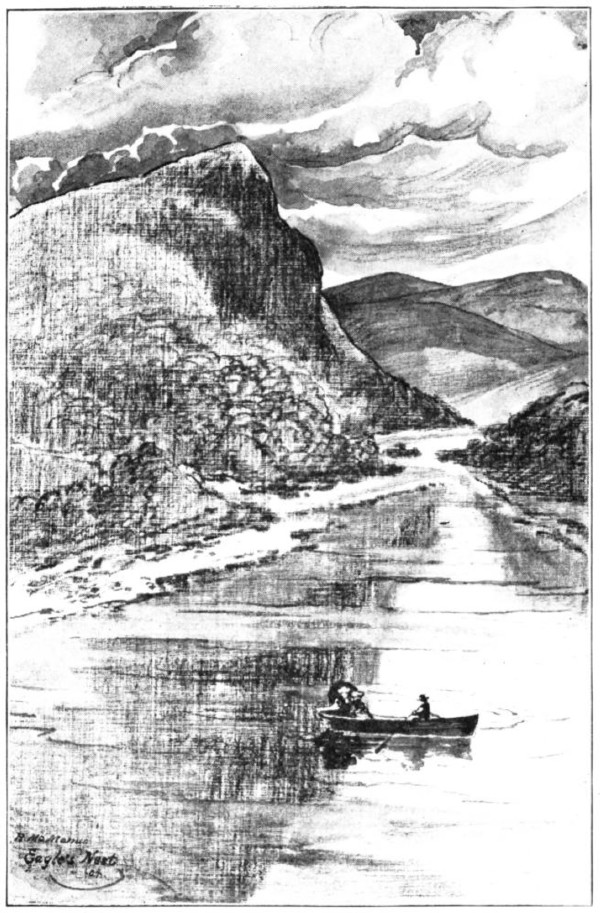

Killarney’s lakes are

irregular sheets of water lying in a basin at the foot of a very high

range of mountains, set with islands and begirt with rocky and wooded

heights. They are three in number; what is known as the upper, the

middle or Muckross Lake, and the lower lake, — the northernmost, —

more properly called Lough Leane. The middle lake is also called the

Torc. A winding stream, known as the Long Range, unites the different

bodies of water. The chief of the natural beauties of the Long Range

is the Eagle’s Nest, which rises sheer from the water’s edge

1,700 feet. The upper lake is the most beautiful of all, though the

smallest of the triad. It is studded with tiny islands and girt with

mountain peaks, bare and stern above, but clothed with rich foliage

at their base. The middle lake is also a beautiful, though more

extensive, sheet, and contains but four islands, as compared with

thirty in the lower lake and six in the upper.

The Colleen Bawn Caves —

reminiscent of Gerald Griffin’s story, “The Colleen Bawn,” and

Boucicault’s famous play of the same name — are also in the

immediate neighbourhood of the middle lake. Torc Cascade and Torc

Mountain lies just to the southward, and is justly famed as one of

the brilliant beauties of the region, as it falls in numerous

sections over the broken rock to fall finally in a precipitous

torrent of foam to its ravine-bed below.

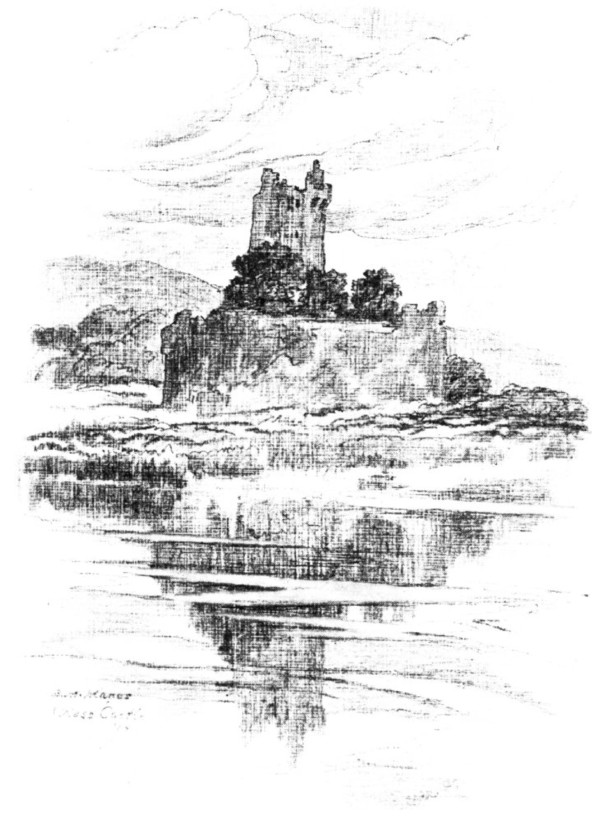

Ross Castle, like

Muckross Abbey, is one of Killarney’s chief picturesque ruins. It

is on an island in the lower lake, and was built ages agone by the

O’Donoghues. It was the last castle in Munster to surrender in the

wars of the seventeenth century, giving in only when General Ludlow

and his “ships-of-war,” as his narrative called them, surrounded

it. MacGillicuddy’s Reeks lie farthest to the westward in the

Killarney region. The name of this stern and jagged range sounds

somewhat humourous, and in no way suggests the majesty and splendour

of these hills; for they resemble the great mountains of other parts

only by reason of their contrast with the low-lying land around their

bases. One portion, indeed, rises a matter of 3,400 feet, and forms

the most elevated peak in Ireland, grand and majestic, but, for all

that, not a great mountain, as is so often claimed by the proud

native. The celebrated Gap of Dunloe is far more deserving for its

natural scenic splendour, and, in its way, rivals anything in

Ireland.

Cloisters of Muckross

Abbey

The popular method of

imbibing the charm of Dunloe is a combination of picnic, al

fresco

luncheons, and donkey-riding. This answers well enough for the

“tripper,” but is as unsatisfying to the real lover of nature as

an imitation Swiss châlet

set out in a London park, or a Japanese tea-garden built out of

bamboo poles from Africa.

The Gap of Dunloe is a

grand defile, perhaps five miles in length, which can only be

explored and truly enjoyed by a pilgrimage along its solitary and

rugged road on foot. Its scenic aspect is gloomy and grand, with

mirrored lakes, lofty mountains, and a thick undergrowth of heather

and ivy. It is, however, in no manner theatrical. Through this wild

glen ripples the river Lee, linking its five tiny lakes as with a

silver thread.

At the upper end of the

gap one emerges into “The Black Valley,” somewhat apocryphally

stated to be “a gloomy, depressing ravine.”

THE EAGLE’S NEST.

The sun, it appears, does

not shine down its length for long in the day, as it is flanked on

either side by precipitous hills. The average imagination will not,

however, conjure up any very dark suspicions with regard to its past,

judging from the aspect of the valley between the hours of nine in

the morning and two in the afternoon. Both before and after these

hours there is no sunlight; and, because of the dense, long-reaching

shadows which are projected across it, it was so named.

There is a good week’s

rambling here to spots already famed in history for their beauty; but

one must search them out for himself as a personal experience.

England’s poet laureate

has written in praise of Killarney in a fashion which should please

his severest critics, those who have mourned the lack of a single

thought in his verse. This is certainly not true with regard to his

prose, which, in the following lines, so justly and appropriately

describes the charm of South-west Ireland:

“Vegetation, at once

robust and graceful, is but the fringe and decoration of that

enchanting district. The tender grace of wood and water is set in a

framework of hills, — now stern, now ineffably gentle; now dimpling

with smiles, now frowning and rugged with impending storm; now

muffled and mysterious with mist, only to gaze out on you again with

clear and candid sunshine. Here the trout leaps, there the eagle

soars; and there, beyond, the wild deer dash through the arbutus

coverts, through which they have come to the margin of the lake to

drink, and, scared by your footstep or your oar, are away back to the

crosiered bracken or heather-covered moorland. But the first, the

final, the deepest and most enduring impression of Killarney is that

of beauty unspeakably tender, which puts on at times a garb of

grandeur and a look of awe, only in order to heighten by passing

contrast the sense of soft, insinuating loveliness. How the

missel-thrushes sing, as well they may! How the streams and runnels

gurgle and leap and laugh! For the sound of journeying water is never

out of your ears; the feeling of the moist, the fresh, the vernal is

never out of your heart.... There is nothing in England or Scotland

as beautiful as Killarney; ... and, if mountain, wood, and water,

harmoniously blent, constitute the most perfect and adequate

loveliness that nature presents, it surely must be owned that it has,

all the world over, no superior.”

ROSS CASTLE

|