| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2017 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IV. AROUND THE COAST TO LIMERICK IT is at Fastnet that the great incoming Atlantic liners, bound for Queenstown, or through St. George’s Channel to Liverpool, first make land and run up their four-deep strings of signals; where, as Mr. Kipling says: “Every day brings

a ship,

Every ship brings a word; Well for him who has no fear, Looking seaward, well assured That the word the vessel brings Is the word that he should hear.” Beyond Bantry Bay, Black Bull Head passes on the starboard, and, soon after, Dursly Head and Dursly Island. The island is said to contain a population of over five hundred, with no priest, no public house, and no constabulary. A veritable Arcadia! Bolus Head, Skelligs Rocks, and Bray Head passed, one comes to Valentia Island and the entrance to Dingle Bay. One of the most fondly recalled of all Irish legends is that of the landing of the Milesians, as they came up through the Biscayan Bay upon what they then knew as “Innis Ealga” — the Noble Isle. Then it was ruled by three brothers, princes of Tuatha de Danaan, after whose wives (who were also three sisters) the island was alternately called, Eire, Banva, and Fiola. By these names Ireland is still frequently known to the poets. Whatever difficulties or obstacles beset the Milesians in landing, they at once attributed to the “necromancy” of the Tuatha de Danaans. When the Milesians could not discover land where they thought to sight it, they simply agreed that the Tuatha de Danaans had, by their black arts, rendered it invisible. At length they descried the island, its tall blue hills touched by the last beams of the setting sun; and from the galleys there arose a shout of joy. Innisfail, the Isle of Destiny, was found!

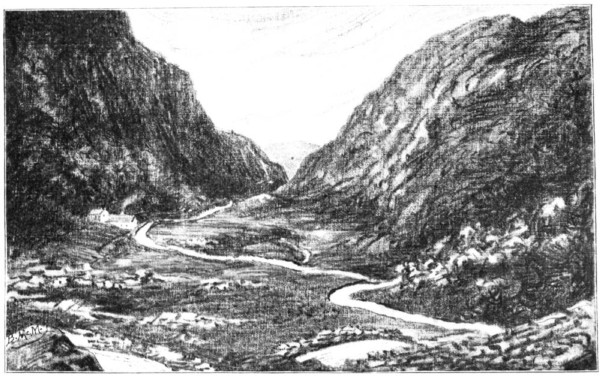

THE GAP OF DUNLOE. The legend has furnished Moore the excuse for launching into melody again. He relates it as follows:

“They came from a land

beyond the sea,

And now o’er the western main Set sail, in their good ships, gallantly, From the sunny land of Spain. ‘Oh, where is the isle we’ve seen in dreams, Our destin’d home or grave?’ Thus sung they, as by the morning’s beams, They swept the Atlantic wave. “And lo, where afar o’er ocean shines A sparkle of radiant green, As though in that deep lay emerald mines, Whose light through the wave was seen, ‘ ’Tis Innisfail — ’tis Innisfail!’ Rings o’er the echoing sea, While bending to heav’n the warriors hail That home of the brave and free.” Valentia — the most westerly railway-station in Europe, says Bradshaw — is the true spot where West meets East; where the New World first receives its introduction to the Old.

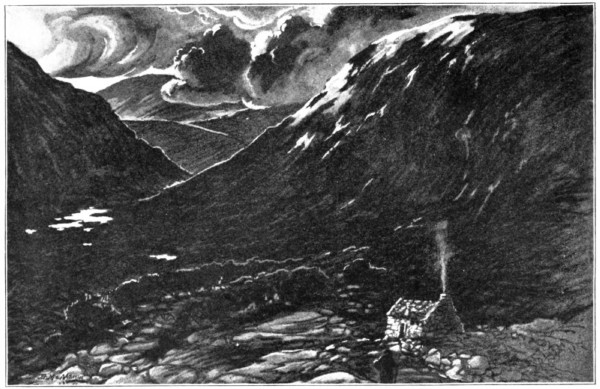

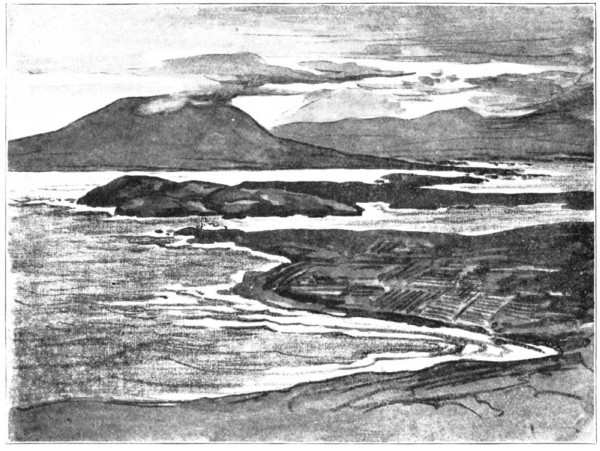

THE BLACK VALLEY. More than half a century ago, the shores of this spacious sheet of landlocked water were selected by the great Duke of Wellington and others as the terminus of a railway which was to be the first link in the chain which was to bind the Old World and the New, and to join the ocean liners that were run from America to Valentia, as they now do to Queenstown. The project fell through, but the island was afterward selected as the old-world end of the Atlantic cable of 1865, and also that laid by the leviathan steamship, the Great Eastern, in 1866. The principal village on the island is called Knightstown. If favoured with a fresh westerly breeze, one beholds from the hillside a scene of grandeur unsurpassed. The ocean engages in conflict with the rugged headlands rising hundreds of feet out of the sea, and hurls its foaming breakers with ceaseless rhythm against the base of the rocks, only to be rolled back in spray and foam. All outside is a scene of wild magnificence, while, such is the perfect shelter, the harbour itself, under all stress of weather, is as placid as a summer lake. Lord John Manners, in his notes of a tour through Ireland, describes the Atlantic here as follows: “The great waves came in with a roar like a peal of artillery, and leapt up against and over the rocks just below us, sending forth a rainbow in one direction, and an immense jet of foam in another. I do not believe I exaggerate in saying that some of the jets of foam sprung a hundred feet into the air, and then the tints! Sometimes a clear green wave would roll its huge volume on the rocks before it broke; at others, dash greenly up to it and dissolve in wreaths of purest white spray, causing, as it broke, a delicate iris to glow on the opposite rocks; while toward the west a veil of foam overhung the coast, lighted up by the golden rays of the setting sun. No words can describe the fascination of the scene.” To observe the contrast between nature and the works of man, one has only to visit the isolated premises of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company. The manner in which electricity outstrips the sun in his daily round is here strikingly exemplified. Happening to be in the instrument-room at about eleven o’clock in the forenoon, one sees the operators at work, receiving from, say, Berlin, the reports of the day’s markets, and transmitting the information to New York, to be served up fresh on Uncle Sam’s breakfast-table, which, even at that early hour is already old news in the Eastern world. Lying just inside Valentia Island is Cahirciveen, the birthplace of Daniel O’Connell, and from this point to Dingle, across the bay, is to be seen — though from the seaward side only — the finest rock scenery on the southwest coast. Here Nature seems to have done her best to produce the picturesque with ocean and rock, twisted and split, pierced and tunnelled; every rock seems to have been torn in some gigantic struggle against total destruction, and left to still wage war against storm and tempest. The harbour of Dingle, landlocked and peaceful, is in quiet contrast to all this turmoil, though Dingle’s weekly cattle fair will give the stranger the impression that he is witnessing something very akin to the fabled Donnybrook Fair, so far as riotous good humour is concerned.

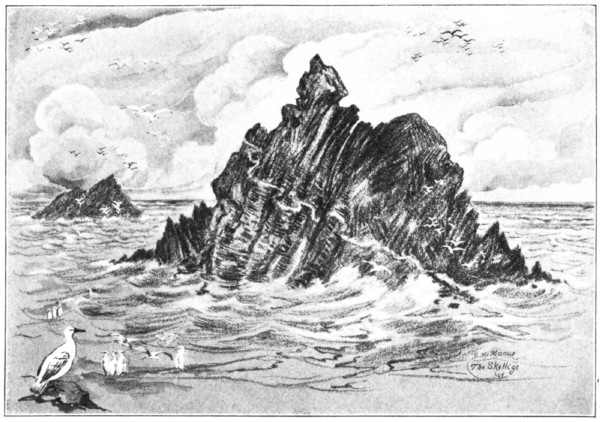

VALENTIA. From Slea Head a magnificent view of Dingle Bay is obtained, — its indented shores flanked by the Dingle mountains stretching away for thirty miles of wonderful panorama of islands and rocks out to and around the Blasquetts. The Blasquetts are a group of eight rocky islands, two of them three miles from the coast. In the sound between these two and the mainland one of the ships of the Spanish Armada sank with all on board. Perhaps the wildest scene on the southern coast is presented by the Skelligs Rocks, off Dingle Bay, rising as pinnacles of slate, wind-swept and bare. The cliffs seem painted in bands of cream colour, produced by countless crowds of gannets — most powerful of gulls — sitting on their nests on the ledges of cliff. At the sound of an approaching steamer, the air is filled with a swarm of puffins, or sea-parrots, which fly heavily around the crags; while, from the caves on the lower cliffs, like crowds of the smaller gulls fill the air with their shrill, screaming cry. Limerick is a city which, by very reason of her great past and her matter-of-fact and decidedly ordinary present, presents great and disappointing contrasts. One may read the statistics in the guide-books and learn that 350,000 pigs are killed every year in the town, and of a great many other mundane things which happen here and have no interest whatsoever for him. There is no doubt about the pigs, sausages, and various pork products, for fat swine, “razorbacks,” big pigs, and little pigs swarm everywhere. There is no escaping the Limerick pig. In single file, in battalions, as solitary scout, alive or dead, baconed and sausaged, he dominates the town. Limerick was in existence as long ago as the days of Ptolemy; was scrambled for by the Danes and the Irish kings in Alfred’s time; took the fancy of that good judge of “eligible sites,” King John, and was decorated with one of his innumerable castles, a fine old relic which still remains. The town was in the very thick of the row raised by Cromwell; and, in the wars of “the silent” William of Orange, it manufactured history as fast as its factories turn out sausages now. The name of Sarsfield, the Jacobite general, is for ever identified with Limerick. The city was taken and retaken more often than we should care to state; it was — and is — fortified up to the very limit; and, whenever anything exciting of a political nature went on, in times past, Limerick was ever to the fore front, ready to emphasize her opinions with the high-shouldered fat little cannon that have somehow got left out on the ramparts, quite forgotten except by “tourist touts,” though, truth to tell, not many tourists ever come to Limerick.

THE SKELLIGS ROCKS. To-day Limerick — in spite of its activities with respect to sausages — is no more a maker of history, but sits dozing complacently on the estuary of “the finest river in the kingdoms,” and cares not apparently for the comings and goings of the outside world. As some poetic soul — possessed by an Irishman of course — has said: “No one cares for Limerick now. Of all the fierce possessors who fought for her when she was young, the local government officially alone remains, like the gray elderly husband of some housewifely woman who was a beauty and a ‘toast,’ and made men’s swords leap from their scabbards for love of her — once.” At the mouth of the Shannon, near where its tidal waters meet the sea, Limerick has its “fashionable watering-place” of the conventional pattern. The chief “amusement” of this delectable place appears to be the gathering of “Irish moss,” as it is commonly known. Here they call it “Carrageen moss,” but it is the same thing, and ultimately turns up as a dainty and nourishing jelly. The peasantry gather it for profit, the visitors for pastime. It is found in many shallow rock pools at low tide, and grows in short, bushy tufts, coralline in shape. The “moss” must be bleached in the sun, and then boiled down into jelly. “Dulse,” another variety of edible seaweed, which requires no preparation, is also found here; and the central ribs of young oarweed are peeled and eaten like celery, which they very much resemble in looks, but — most emphatically — not in taste.

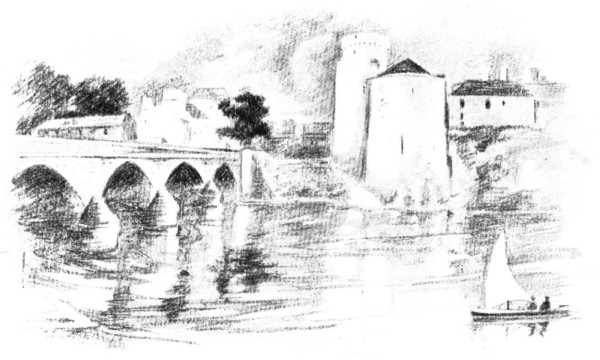

LIMERICK CASTLE. Dear also, to Americans, will be the memory of County Limerick as the birthplace of Fitz-James O’Brien. The son of an attorney, he was born in 1828, receiving his education at Dublin University. In his youth he saw service as a British soldier, but early drifted toward journalism and America. Among his earliest compositions were two remarkable poems, “Loch Ine” and “Irish Castles,” which present in a picturesque vocabulary many of the salient charms and beauties of his native isle. |