CHAPTER V.

THE SHANNON AND ITS LAKES

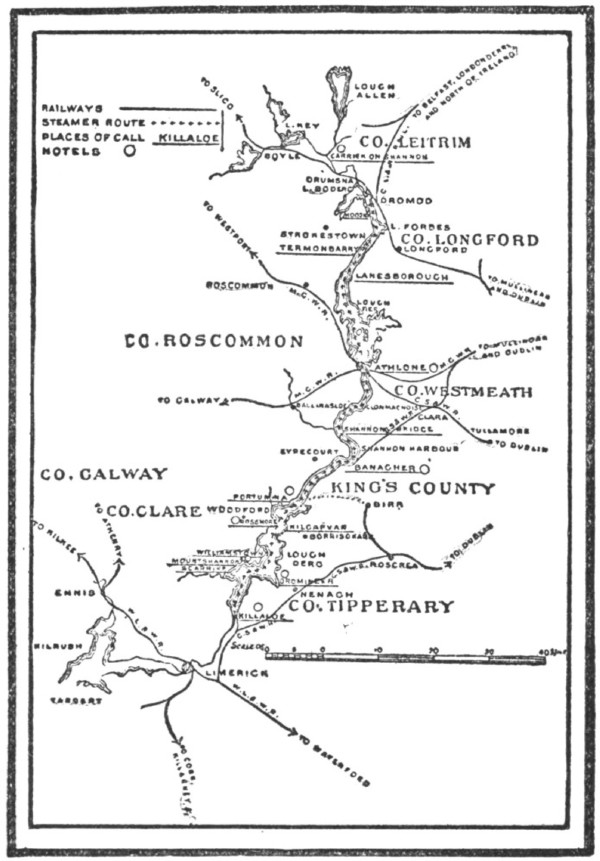

NO river in Great

Britain, neither the Thames, nor the Clyde, nor even the Severn,

equals the river Shannon and its lakes, either in length or in

importance as an inland waterway. The native on its banks tells you

that it rivals the Mississippi; but in what respect, Americans, at

least, will wonder. Except that it broadens to perhaps a dozen miles

in the widest of its lakes, there is, of course, no comparison

whatever. The traffic on the river is of no great magnitude compared

with that on the Thames and the Clyde; but, were there a demand for

such, its capacity would be far greater than either.

Moreover, for beauty,

either of the dainty and popularly picturesque sort, or of the

supremely grand, it has preëminence, and one can journey its whole

length, from Killaloe, practically a suburb of Limerick, to

Carrick-on-Shannon, something over a hundred miles, in steamboats of

really comfortable, if not exactly luxurious, appointments.

It is the tourist traffic

mostly that is catered for; and the traveller, in the season, is

likely to find the company mixed, though by no means is it of the

“tripper” class.

The itinerary comprehends

much that is beautiful and much that is historic.

From Limerick, one

usually makes his way by train, although he may go by car or coach, —

such a trip is well worth while, — and embarks upon the tiny

steamer at Killaloe.

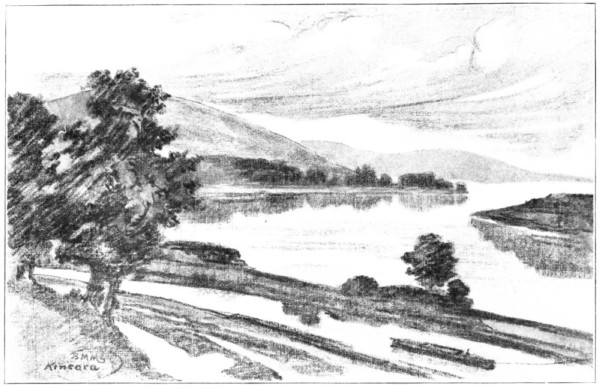

Here, at the lower end of

Lough Derg, near Killaloe, stood in the ninth century Brian Boru’s

palace of Kincora. The mound on which it was built is all that

remains of a place that displayed, twelve hundred years ago, the

greatest glory of the proud Irish kings.

THE SHANNON AND ITS LAKES

Many were the events of

historical moment which took place here, though, as a palace of great

splendour and magnitude, it may have been exceeded by Tara and

Emania.

KINCORA.

The memory of Brian

Boru’s life here places him in the annals of the world’s great

rulers as “every inch a king.”

Neither on the Irish

throne, nor on that of any other kingdom, did there ever sit a

sovereign more splendidly qualified to rule; and Ireland had not for

some centuries known such a glorious and prosperous, peaceful, and

happy time as the five years preceding Brian’s death. He caused his

authority to be not only unquestioned, but obeyed and respected in

every corner of the land. So justly were the laws administered in his

name, and so loyally obeyed throughout the kingdom, that the bards

relate a rather fanciful story of a young and exquisitely beautiful

lady, who made, without the slightest apprehension of violence or

insult, and in perfect safety, a tour of the island on foot, alone

and unprotected, though bearing about her the most costly jewels and

ornaments of gold. This legend will be further recalled by the memory

of the well-known verses beginning “Rich and rare were the gems she

wore.”

It was at Kincora that

the following incident took place:

Mælmurra, Prince of

Leinster, playing or advising on a game of chess, made or recommended

a false move, upon which the patriotic Morrogh, son of Brian,

observed that it was no wonder Mælmurra’s friends, the Danes (to

whom he owed his elevation), were beaten at Glenmana, if he gave them

advice like that. Mælmurra, highly incensed by the allusion, — all

the more severe for its bitter truth, — arose, ordered his horse,

and rode away in haste. Brian, when he heard it, despatched a

messenger after the indignant guest, begging him to return; but

Mælmurra was not to be pacified, and refused, and concerted and

connived with certain Danish agents, always open to such

negotiations, those measures which led to the great invasion of the

year 1014, in which the whole Scandinavian race, from Anglesea and

Man, north to Norway, bore an active part.

AN IRISH PIPER.

While Brian was residing

at Kincora, news was brought of his noble-hearted brother’s death,

whereupon he was seized with the most violent grief. Brian’s

favourite harp — always a legendary and traditional symbol of Irish

emotions — was taken down, and he sang that famous death-song of

Mahon recounting all the glorious actions of his life. “His anger

flashed out through his tears as he wildly chanted the noble lines,”

say the chronicles.

“My heart shall burst

within my breast,

Unless I avenge this

great king.

They shall forfeit life

for this foul deed,

Or I must perish by a

violent death.”

Of the passionate

attachment of the Irish for music, little need be said, as this is

one of the national characteristics which has been at all times most

strongly marked, and is still most widely appreciated, the harp being

universally held as a national emblem of Ireland. Even in the

pre-christian period that we are here reviewing, music was an

institution and a power in Erin.

Few spots in Ireland are

richer in historical and archæological interest than Killaloe. There

is a fine specimen of sixth-century architecture in the

well-preserved cell of St. Lua, with its steep roof of stone and

cunningly devised arches. It is a venerable building, and nestles

under the shadow of the present Protestant cathedral, built by

O’Brien, King of Thomond, in the twelfth century. On a small island

in the river Shannon are the ruins of an ancient friary, and at a

little distance the remains of a small chapel. These are said to mark

the position of a ford used by pilgrims who came to visit Killaloe

before the bridge, which is itself ancient, was built.

Lough Derg is reputedly

one of the prettiest pieces of water in Ireland. Its shores are well

wooded, and the background all around is made up of swelling upland,

dotted here and there with the white houses of the peasantry, while

in the far distance are the heather-clad hills of the Counties Clare,

Galway, and Tipperary.

In Lough Derg, on Station

Island, is the reputed entrance to St. Patrick’s Purgatory. A

wide-spread superstition accounts for its popularity, but whether as

a purely “tourist point” or as a place of pilgrimage for

penitents, it were better not to attempt to judge.

Tradition has it that St.

Patrick had prevailed on God to place the entrance to purgatory in

Ireland, that the unbelievers might the more readily be convinced of

the immortality of the soul and of the sufferings that awaited the

wicked after death. A few monks, according to Boate, an old Irish

writer, dwelt near the cavern that formed the entrance. “Whoever

came to the island with the intention of descending into the cavern

and examining its wonders had to prepare himself by long vigils,

fasts, and prayers, to strengthen him, as we are told, for his

dangerous expedition; but, in reality, by reducing his bodily

strength to make his imagination more ready to receive the

impressions which it was thought desirable to leave upon his mind. He

was then let down into the cavern, whence, after an interval of

several hours, he was drawn up again half-dead, and, when he

recovered his senses, mingling the wild dreams of his own imagination

with what the monks told him, he seldom failed to tell the most

marvellous tales of the place for the remainder of his life. It was

not till the reign of James II. that the monks were driven away from

the place, and the mystery of the dark cavern dissolved.”

From Killaloe to

Portumna, the Shannon flows through Lough Derg, a wide-spread

waterway, an elaborate expansion of the river itself. This lake,

which is twenty-five miles long and from two to six miles in breadth,

has an average depth of about fifty feet. Close to Portumna is the

Castle of Ballynasheera, said to have been once the residence of

Ireton, Oliver Cromwell’s son-in-law.

From Ben Hill, a few

miles below Portumna, near Woodford, is a splendid view of Lough Derg

and the surrounding country. The lake here stretches along between

the Slieve Aughty Mountains on the Connaught side and the Arra

Mountains on the Munster side, whose lofty summits tower up high into

the clouds. The shores, sloping gradually down to the water, are

covered with luxurious foliage, through openings in which may be seen

the ruins of many an ancient castle and once stately mansion.

Portumna itself is a

flourishing town, but of no great antiquarian interest. The

population of town and district is about two thousand.

Near by is Victoria Lock,

Melleek, adjacent to which are two strongly built towers, which

formerly mounted eight guns, and which, in more romantic times, were

erected to guard the pass of the Shannon between Connaught and

Leinster.

The Stone of the

Divisions, Westmeath

Shannon Harbour, at which

the Grand Canal joins the Shannon, is situated on the river about six

or seven miles from Shannon Bridge, and is immortalized by Charles

Lever in “Jack Hinton.”

As a tourist resort the

town appears to have degenerated sadly, a pretentious hotel

establishment having been converted over into barracks for the

constabulary.

From Shannon Harbour the

steamer passes Shannon Bridge, and in due course reaches Athlone at

the lower end of Lough Ree. “Population, seven thousand. Industry,

manufacture of the celebrated woollen tweeds, which provides

employment for several hundred operators, both male and female; there

are various other smaller manufacturing industries pursued by the

town population. In the rural districts, cattle rearing, both in

Westmeath and Roscommon, and the pursuit of general agriculture is

principally followed, and the inhabitants of these rural districts

are generally comfortable and fairly well-to-do.” Such is the usual

guide-book information concerning Athlone, which lies at the juncture

of Roscommon and Westmeath.

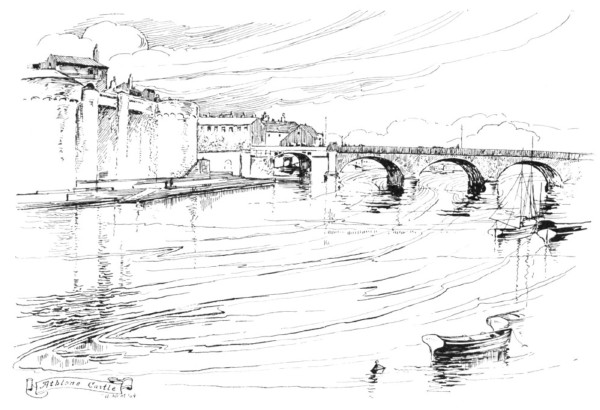

As a matter of fact,

however, almost every stone in the prosperous little city has a

historic interest and value, from the ruins of its former splendid

ecclesiastical establishments to its old houses and still more

ancient fortifications, and the castle erected in 1215 by King John,

— a counterpart in every respect of a similar establishment at

Limerick. Queen Elizabeth made Athlone the capital of Connaught.

After the battle of the Boyne, it underwent two sieges from the

forces of King William. Some traces of the old fortifications may be

seen, and the castle is still in perfect repair.

Just north of Athlone,

where the Shannon joins Lough Ree, is Auburn, more popularly known as

“Sweet Auburn,” whose old ruined parsonage is famous as the early

home of Oliver Goldsmith.

ATHLONE CASTLE.

Fleeting time has changed

this modest mansion — whose ruin was deplored by Goldsmith himself

— but little. It stands about a hundred yards from the public road

at the end of a straight avenue bordered with ash-trees, — a plain

rectangular, two-storied house, built in the ugly and uncompromising

style that was popular in Ireland in the early part of the

seventeenth century. The roof is off, but the walls remain, and seem

still to be haunted by the shade of the Rev. Charles Goldsmith, the

original Doctor Primrose in “The Vicar of Wakefield,” while his

wife, hospitable as of yore, still seems to invite the passing

stranger to taste her gooseberry wine. The famous inn, — since

rebuilt out of all resemblance to its former self, — immortalized

by Goldsmith, and known as the Three Pigeons, where were drawn the

“inspired nut-brown draughts,” and “where village statesmen

talked with looks profound,” is but a little distance from the

house. The country all around Lishoy — for that is the name of the

townland in which Toberclare, this Mecca of the Goldsmith student, is

situated — is well wooded and cultivated. The drive from Athlone to

“Sweet Auburn” is one of the most delightful in Ireland. As the

reputed locale

of “The Deserted Village,” Auburn, or Lishoy, as it was formerly

known, has an unusual share of interest for the literary pilgrim.

Goldsmith was not born

at Lishoy, as is sometimes stated, but in Pallas, a village in the

County Longford, his father being at the time a poor curate and

farmer. The infancy of Oliver was, however, spent in Lishoy, and

there is little doubt but that the scenes of his childhood became

afterward the imaginative sources whence he drew the picture of

“Sweet Auburn,” though it is doubtless true that the descriptions

are general enough in character to apply to many localities in

England as well as Ireland:

“Sweet Auburn!

loveliest village of the plain,

Where health and plenty

cheer’d the labouring swain;

Where smiling spring its

earliest visits paid,

And parting summer’s

lingering blooms delay’d.

Dear lovely bowers of

innocence and ease,

Seats of my youth, when

every sport could please;

How often have I

loitered o’er thy green,

Where humble happiness

endear’d each scene!

How often have I paused

on every charm!

The shelter’d cot, the

cultivated farm:

The never-failing brook,

the busy mill;

The decent church that

topp’d the neighbouring hill;

The hawthorn bush, with

seats beneath the shade,

For talking age, and

whispering lovers made.”

Attempts have been made

from time to time to justify the procedure, which is customary here,

of stripping the hawthorn of its blossoms to sell to tourists; and to

explain that it is a perfectly legitimate and artistic thing to have

hung the old broken plates and cups of the erstwhile Three Pigeons on

the walls of the new inn. Sir Walter Scott attempted to justify all

this as “a pleasing tribute to the poet,” but there is a hollow

mockery about it all that will make the true pilgrim hasten to

commune with “The never-failing

brook, the busy mill;”

and

“The decent church that

topp’d the neighbouring hill,”

all three of which exist

to-day, and bear a far greater likeness to the description of the

poet than does the reputed inn.

Through Lough Ree one

journeys along historical ground. Rindown Castle was built, it is

said, by Turgesius, a Dane, who made of it an impregnable stronghold,

as may be readily believed when one views its rocky promontory.

The island of

Inchcleraun, commonly called “Quaker Island,” is associated with

early Celtic Christianity, and has on it the remains of six churches.

On this island, Queen Meave is said to have been killed, while

bathing, by an Ulster chieftain, who threw a stone from a sling while

standing on the shore.

Knockcroghery Bay leads

to Roscommon, the chief town of the county of the same name. It had

its origin at the time when St. Coman founded a monastery there, and

to-day may still be seen elaborate remains of a former Dominican

establishment of the thirteenth century, and of a fortified castle of

the same era.

At the head of the

eastern arm is All Saints’ Island, on which are the well-preserved

remains of a church and monastery, — an ancient foundation which,

in the seventeenth century, was occupied by the nunnery of the Poor

Clares, but was burnt by the soldiery in 1642. It is recorded that

the peasants of Kilkenny West retaliated by killing the destroyers.

Inchbonin, the “Island

of the White Cow,” contains the remains of a church and monastery,

the foundation of the religious house being attributed to St. Rioch,

a nephew of St. Patrick. Here, also, are the remains of several

Celtic crosses.

Entering the Shannon

proper again at Lanesborough, one finally reaches Carrick-on-Shannon,

in itself uninteresting enough, but a centre from which a vast amount

of profitable knowledge may be obtained. It is the gateway of the

pretty valley of the river Boyle, where stands the pleasant little

town of the same name, with its famous abbey, which is in rather a

better state of preservation than many “chronicles in stone.” The

choir, nave, and transepts are all in existence, and show, in their

construction, all the elements of the West Norman and Gothic work of

their time. The nave, with its hundred and thirty-five semicircular

arches, which separate it from its aisles, is perhaps the best and

most characteristic Norman feature, if we except the square heavy

tower. In 1235, the English sacked these sacred precincts, and even —

it is said — stripped the monks of their gowns. In 1595 it was

turned into a fortress and besieged by the army of the Earl of

Tyrone.

From the “Hibernia

Illustrata” we learn that, “In the cemetery of Kilbronan, not far

from Boyle, was buried the famous Carolan, one of the last of the

veritable Irish bards; and here for several years the skull that had

‘once been the seat of so much verse and music,’ was placed in

the niche of the old church, decorated, not with laurel, but with a

black ribbon. He died in the neighbourhood in the year 1741, at a

very advanced age, notwithstanding that he had been in a state of

intoxication during probably seven-eighths of his life.”

From this we may infer

that, if liquor was not more potent in those days, it was at least

less expensive.

|