| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

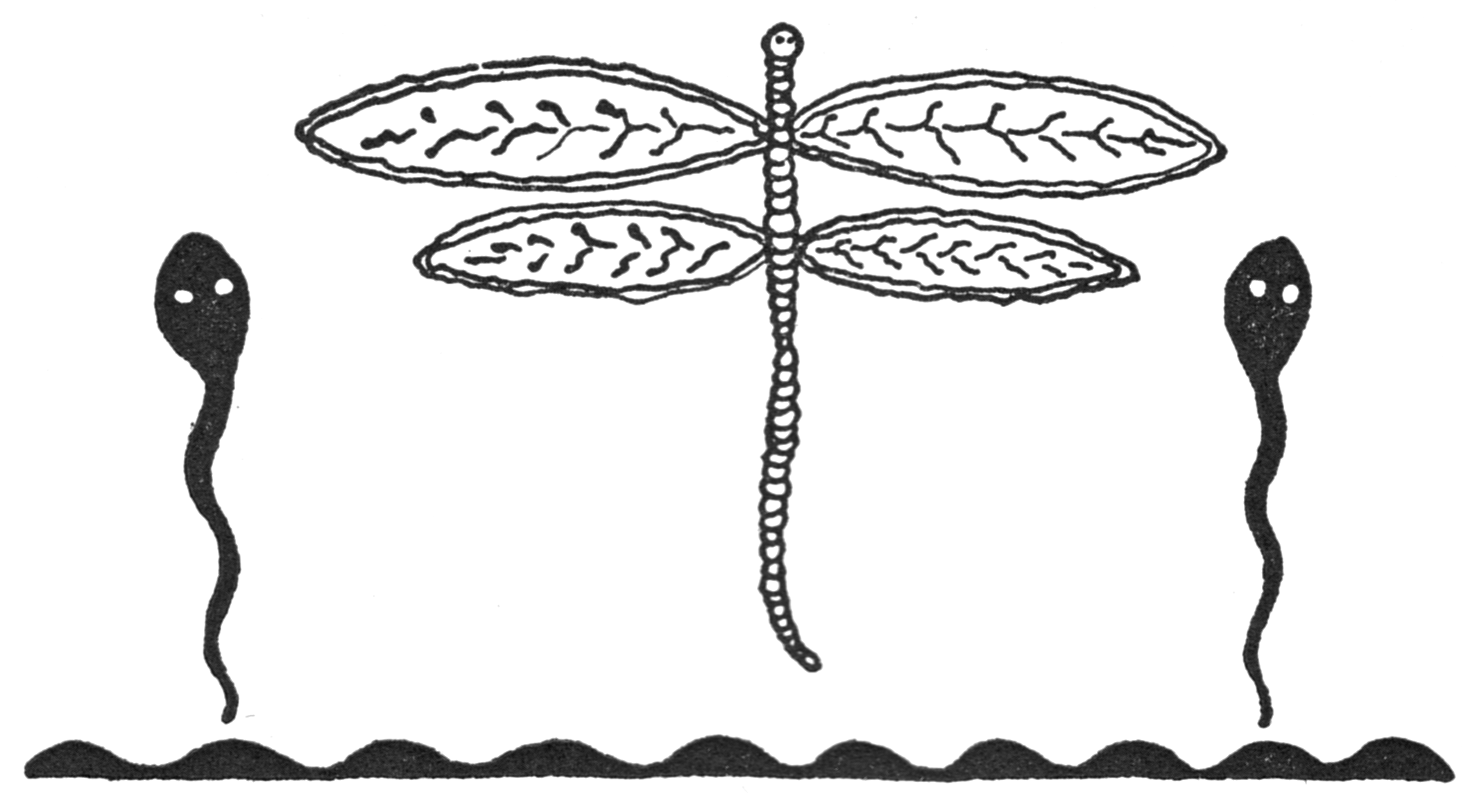

X THE DRAGON FLY  ERY

long, long ago Háwikuh was the largest of all the Cities of Cibola, and

therein

dwelt the chief-priests of Shíwina. The plains below the terraced

houses were

covered with the washes of spring streamlets, and the mists from the

hot

springs, not far distant, drove away the breath of the Ice God, so that

cold

never grew great in the valley. Thus it happened that year after year

more corn

grew for the people of Háwikuh than they had need for, and they became

rich and

indolent with plenty. ERY

long, long ago Háwikuh was the largest of all the Cities of Cibola, and

therein

dwelt the chief-priests of Shíwina. The plains below the terraced

houses were

covered with the washes of spring streamlets, and the mists from the

hot

springs, not far distant, drove away the breath of the Ice God, so that

cold

never grew great in the valley. Thus it happened that year after year

more corn

grew for the people of Háwikuh than they had need for, and they became

rich and

indolent with plenty.One day the Chief Priest of the Bow saw some children playing at warfare in the middle court of the city. They were amusing themselves by throwing lumps of mud at each other. "Ah, ha!" thought the old Priest. "I have a plan, and my people will be delighted. It will also be an excellent way of showing those of the other towns how far above theirs is our wealth and good fortune." He called together a great council of all the warriors and priests and said, "Why should we not order our people to prepare, for four days, great stores of sweet mush, bread, cakes and all kinds of seed foods as for a festival? Then will we send swift runners to the villages and bid the people come and share in our amusement. "We will choose sides for a sham fight," he continued to explain to them. "And we will use for our weapons the good things piled in the ceremonial baskets and heaped into the bowls. The others will wonder at our wealth when they see us treat these things for which men work so hard that they may eat, as children treat mud in the streets." And so it happened that the Chief Priest, big-hearted with conceit, mounted to the house-top at sunset, and ordered the people to busy themselves with the preparations for the great game. Swift young men were sent to the towns around to summon visitors for the day that had been named. And women and maidens bent over their grinding bins, and the yellow meal and the white, was heaped high on trays and in baskets. Now there lived far up the valley, among the White Cliffs, two beautiful goddesses, the Maidens of the White and Yellow Corn. These two sisters were very sad when they saw that their children were about to treat so lightly the gifts they themselves had given them. "Yet," said they, "we will give them one chance. There is but little in their foolish heads, still their hearts may be kindly." They disguised themselves as poor and ugly women, and the day before the great festival, went to the city of the White Flowering Herbs. When they entered the town a misty, drizzling rain preceded them, for were they not the lovely Maidens of Summerland? They slowly passed each open doorway, but no one bade them enter. Heaps of baked things steamed in every corner, but no one gave them food to eat, — no one, save a little boy and his tiny sister. When these children saw how tired and hungry the poor girls looked, they stretched out their little hands, and offered them the corn-cakes they had been munching; but the people from within the house called out in harsh voices, and with ugly words drove the Maidens on. Away down at the end of the town was a broken old house that belonged to a very poor, aged woman who lived all alone. Her clothes were patched and ragged, her blanket torn, and she had but little corn. No one ever entered her house, and people rarely spoke to her except to abuse her. Now it happened that the Maidens, after passing slowly by each house in the village, wandered down the hill toward the old woman's doorway. The old mother saw them and called to them in a quavering voice. — "Come, my poor girls, come in and rest yourselves and eat, for hunger will soften my coarse food. You must have come far for you look so tired and hungry. Never mind, my children, rest here a moment and eat, then go into the town where the people have cooked more food than you ever saw before, and there you may truly feast." The Corn Maidens entered the little house, and the old woman threw down the shredded mantle from off her shoulders and bade them sit on it. Then she placed mush in a bowl and set it before them. Once more bidding them eat, she went away and busied herself about something else, to show them that she did not herself need the food, and that there would be plenty for them. "You are a good and gentle old mother," said the elder of the two girls, and they went for her, and made her sit with them on the mantle. Then they drew forth a beautiful white cotton robe, and unrolling it, took out packages of honey-bread and pollen. They scattered the pollen over the mush, and the odors from the rising steam were as the fragrance of a valley of flowers. At once the old woman knew that these poor girls were not as they seemed, but Beings like the Gods themselves. The poor creature feared that she had offended them by offering her modest food; but the Maidens reassured her, and told her that in all Háwikuh only herself and two little children had shown a sacred heart. The Maidens then passed their hands over their persons and their ragged garments fell from them, leaving such beautiful raiment as man had never before seen in Háwikuh, and their faces seemed to shine with a strange light. The Corn Maidens talked and laughed with the little, old woman; and before they left, they gave her many little bundles from under their mantles. "Place these on the floor of your store-room," they said. And they gave her each a mantle, and told her to hang them on her blanket-pole. And the store-room was filled to the rafters with corn and melons; and the blanket-pole was heavy with beautiful embroidered robes. Then the Maidens smiled and left the house of the little old woman. Some people thought that they had seen two beautiful Beings pass at twilight, but they did not heed them. Only one very old man sat in a corner and mumbled a prayer. "Alas, my foolish people! Did you not see the mist-rain?" As the moon rose out of an arm in the Vale of the White Cliffs, a little squirrel and his brother, the Mouse, sat on a great rock and whistled. In a very short while every little animal in the valley heard the call, and the high rock where the squirrel and the old mouse sat, was completely surrounded by mice, wood-rats, squirrels, gophers, prairie-dogs, crows, blackbirds, sparrows, beetles and insects of all kinds. Everyone talked at once, and finally the old mouse stood up and squeaked and told them to be silent and hear what the squirrel had to say. Then the little squirrel puffed himself out and said, "It is not for nothing that we have brought you here. The Maidens of the White and Yellow Corn have instructed us to make known to you, seed-eaters of Shíwina, their wishes. They are very sad, and greatly vexed with their children, those big fellows who live on Háwikuh hill and plant corn. They want us all to dig and creep and fly and crawl into their fields and store-rooms, and carry off all their corn grain, and in fact everything that we can possibly lay hold of. This is the wish of the sacred Maidens, so do you all go and obey them." Again there was a frightful noise. They squeaked, piped, twitted and chirped; but after they had decided just what each one should do, all was silent,' and the old moon looked down on the sleeping fields and meadows. The Háwikuh people woke early the next morning, and dressed themselves in their finest mantles and put on their most treasured necklaces. And it was well, for strangers from the towns round about were coming in over the trails when the sun rose. All was in readiness, the house-tops were covered with baked things, and the dance-courts were swept clean for the battle. The chief warrior-priests chose sides and the fight began. The people shrieked with laughter at first; but it was not a beautiful sight; and as the day lengthened, dresses were covered with batter and meal, and there were some, among the young men, who grew angry and fell to quarreling. And when night came everybody was disgusted with everybody else; and so the town grew silent soon, and the seed-eaters rushed in and carried away every piece of food, every crumb, every meal-grain. So it came about that when the people looked upon their city the following day, great was their surprise to see not a trace of the abundant supplies wasted, lying about in the courts and the streets. They visited their store-rooms and found them empty, and then they knew that they had offended the Gods. There was nothing for them to do but to leave their proud city, and ask for help from the people they had tried to humble. After some days they started off, a great band moving across the valley. Of course no one thought to tell the old poor woman, and so she was left behind. And as her store-room was filled with the gifts of the Corn Maidens, and the seedeaters had spared it, she never left her home, but remained happily within. There was of course great confusion when so many families were preparing to go for a long stay with neighbors, and in the excitement of the departure a little boy and his tiny sister, the very ones that had offered their corn-cakes to the Corn Maidens, were forgotten. They had been asleep in an inner room of their house, and had not heard the tramping of the many feet as they went over the terraces and down the hill side. At last the little boy woke up. He looked about the big bare room, and then he went through the still house. He was at first frightened, and cried a little, but thinking of his tiny sister, he gathered some splinters and cedar-bark and laid them on the hearth and built a little fire. During this time the little girl slept, and as she dreamed she asked for corn. The boy knew that there was nothing to eat in the house, for had he not heard the old ones talking, and did he not know that all seed-food had vanished. He was hungry and he wondered what he should do. He went to the house-top and there he saw some little chickadees hopping about. "Ah!" said he with delight, "I well remember how the large boys caught these little creatures, and cooked them for make-believe feasts. My little sister and I will have something to eat." He ran down the ladder and over to an old buffalo robe lying in a corner. He pulled some long hairs from the tail, and these he tied into nooses and fastened them over some little cedar branches. He planted his little noose springs all around in the snow on the house-top, and the birds which kept fluttering about, now and then lighted in his snares. He roasted the little birds over the coals of his fire, and the children ate and were happy for the moment. But soon the little girl cried for her mother, and for parched corn, and as the days went by, and their only food was the little birds caught in the hair snares on the house-top, the younger child became weak and sickly. The boy tried very hard to comfort her, and one day he said, "Little sister, hush! I have found the strangest creature down in the field where the corn grew. I will make a little cage for him, and then 1 will catch him and put him into it. Then I will hang the cage over your bed, where you may watch him." The boy hastened away to the fields. He gathered a bunch of grass straws and some stalks of corn, and running home with these, he sat down by the side of his little sister, and began to make the cage. He cut the straws all of one length and strung on them sections of the pith from the corn-stalks. Then passing more of the straws through the pith the other way he at last built up a beautiful little cage. Finally the little girl, tired of watching him, fell asleep. Then the boy hastened to cut a ball of pith. This he fastened to a longer piece, which he painted at one end; and cutting some pieces of the pith very thin, he fastened them into the sides of the long piece near the ball. He was trying to make a butterfly, but the pith was so narrow, and his knives so rough, for they were made of flint chips, — that he could not make the wings broad enough, so he made four long wings instead of two. He took six little straws, and bending them, stuck them into the pith under the wings for legs. When he had finished, he painted big black eyes on the head, and he tried to paint the body and wings with red, green, white and black, but being only a little boy, there were more bands and stripes than dots on the little image. However it looked just like a wonderful creature, and the little boy hung it by a hair in the cage which he suspended over the little girl's bed. When the child woke up she laughed and chattered for joy. She would sit there day after day talking to the pretty toy. Once she said, — "Dear Treasure, go bring me corn grains that my brother may toast them, for you have long wings and can fly swiftly." Wonderful to relate the little image fluttered its wings till they hummed like a sliver in a wind-storm, and the cage whirled around, but presently grew still again. The boy thought it was the wind blowing his cage and the wings of the "butterfly," but the little girl clapped her hands and cried, — "O brother, just see! My butterfly heard me, and fluttered his wings!" That night when the little sister had gone to sleep, the boy lay there watching the moonlight through the sky-hole. Suddenly he heard a buzzing and hissing. "Let me go; let me go," it said. "Hush, or you will wake little sister! Where are you?" said the boy, his heart thumping very hard. "Here I am," buzzed the sound. And looking up the boy saw that the cage of straw was whirling round and round, and the "butterfly" was trying to fly away with it. "Poor thing! I didn't know it was alive. It must be hungry," thought the boy — for he was nearly always. hungry now so he said: — "Wait, wait, my little butterfly, and I will let you go." He softly got up and opened the cage, and the creature hummed, and flew swiftly about the room. "My little father," he said quite near to the boy's ear. "Your heart is better than many men's together. You have given me a body, and you have loved your poor, little sister faithfully and well. I will fly away, but fear not, I will return." The boy, scared and wondering, watched the creature. It flew around the room once or twice, and with a twang like a bowstring, and a flight swift as the arrow's, shot up through the sky-hole and out into the night. Now this corn-stalk being flew straight away to the westward until it came to a great lake. Over the dark, deep waters shone a thousand dim lights, and two ugly, but good persons, were pacing the shores, calling out loudly to one another. They were the ancients of the Drama, watching for the coming of men's souls. The "butterfly" never stopped to speak to them, but plunged at once into the clear, cold waters. In an instant he was below, in great blazing halls filled with the Gods of the Spirit World, and the happy souls of men. The little creature darted back and forth, and finally the God of Fire asked him if he brought a message. After a good deal of buzzing, he settled on a mantle rack and spoke. "I come from Shíwina, and I beg you to lay the light of your favors on two poor children. One gave me this form, and it is fitting that I become their messenger. Then he told the Gods the story of the little boy and girl that were left in Háwikuh. "Happily will we help our beloved little ones," said the Gods. They summoned the swift footed runners of the Sacred Dance, and bade them take pouches of corn grain from the seed stores of the creatures of the Valley of the White Cliffs, and place them in the store-room of the children's house. Then they said to the "butterfly," — "Hasten away to our sisters, the Corn Maidens, and tell them your story. Do you also instruct the boy to make prayer-wands for us, and tell him that he shall receive great blessings." So the Corn Being buzzed around the great hall, and then flew back to Háwikuh, and straight into his cage. When it grew light, the little boy, quickly putting the cover from his head, looked up. There in the cage hung the little painted toy that he had made. He thought that he had had a wonderful dream; but the door of the store-room stood open, and corn, beautiful white and yellow corn, was piled high within. Everything was well with the children for some time; but again the little girl grew unhappy. She grieved for her mother. Again the "butterfly" buzzed in the night, and the boy let him go. He told the boy to prepare plume-offerings, and instructed him as to how they should be made. Then he flew out into the darkness. This time he flew to Summerland, and to the home of the Corn Maidens. He told the beautiful Beings the story of the children of Háwikuh. "It is well that you have come to us," they said. "Proceed us, little father. It will be ever so, we will follow you into the lands of mortals." And then they wrapped themselves in a fine mist and journeyed to Háwikuh. They first went to the home of the old woman who lived alone, and they told her that there were also two little children in the deserted town, and that she must go to them and comfort the little girl child. Then they went to the house of the little ones, and, entering the room as softly as the moonbeams, each Maiden took a child in her arms, and comforting them, asked what wish was nearest their hearts. "I want my little mother," cried the baby girl. And the boy, made older by much thinking, said, — "O, beautiful Maiden-mothers, let my people return to their city; and may you smile upon the summer fields again, and plenty will bless our land. Surely through much suffering, the hearts of our old ones are made sacred, and wisdom will sit at the council of men." The Corn Maidens smiled at each other, and the elder told the boy that they would send a messenger to his people, bidding them return to their homes. "On the fourth day from this," said the younger Maiden, "warm rains will come and they will drive away the snow from the mountain tops, and bring the springtime. The meadows will be covered with flowers, and the young corn, high in the fields to greet the returning people." The little boy knelt at their feet, and pressing their hands against his cheeks, thanked them. Early the next morning the little, old woman climbed up the terraces to the home of the children. She took the tiny girl in her gentle arms and the child was happy. That night the corn-stalk creature buzzed, and the boy let him free. "Tonight I must leave you," said the strange Being. "Our Fathers, the Gods of the Spirit World, have blessed you with great goodness of heart and wisdom, and you are to be the Boy-Chief-Priest of your people. The day after tomorrow the warriors and priests will return to Háwikuh, followed by the people. Do you dress yourself in the sacred robes the Corn Maidens gave to you, and await their coming. "Give to me the plume-offerings that you have made for the Gods, and I will fly to the Lake of Hereafter, and place them on the sacred altars there." So gathering together the spirits of the feather-offerings, the Dragonfly, for that is what he really was, sailed off to the Hall of the Gods. The boy became the Chief Corn Priest of his people, and the little girl and the old, poor woman were treasured by them. And as the Corn Maidens had promised,. the Dragonfly returned to the land of Shíwina every year bringing the message of the coming of Spring. |