| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XII THE YOUNG HUNTER  ONG,

long ago, there lived in the Village of the Winds a big young fellow,

greedy,

and as slow witted as a horned toad. Why, he didn't even know a pumpkin

from a

melon. His father and mother had died, so there he lived all alone with

his

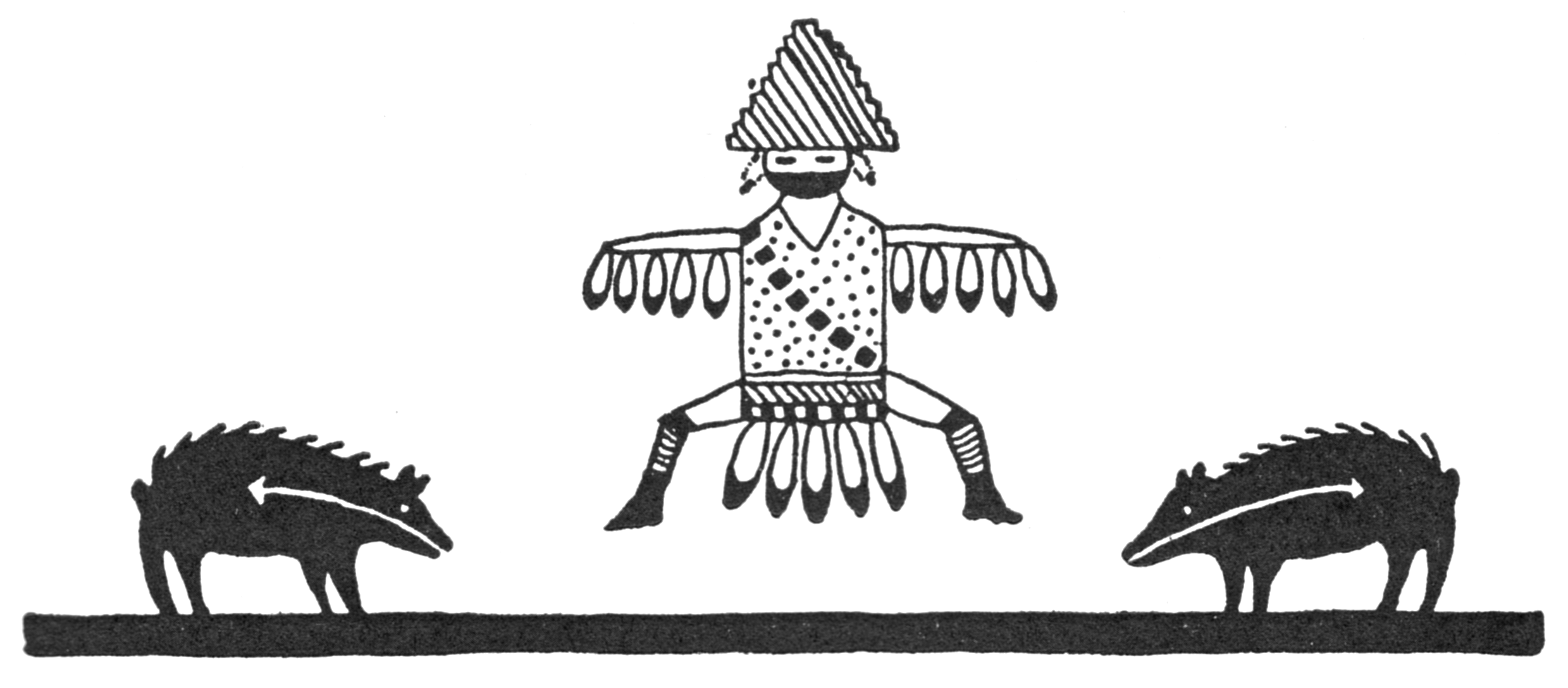

sputtering old grandmother.

Now the young man was very strong, and he also was very good looking, except that he was too fat. And good natured was he, as is the custom of slow thinkers who have to wait too long for a bad word to blister, or an insult to prick. One day he spoke to his old grandmother. "It is time that I should marry," he said, "I will bring a lovely maiden to your fire-side." "Is that so?" croaked the old woman. "Who would look with favor upon you, fat as you are, and lazy? Surely a maiden would shudder if she saw the quantity of corn you eat at a single meal. Her days would indeed be spent bending over the grinding bin." After hearing these words the youth became thoughtful; in fact, he brooded so much over them that he began to get lean, and to lose his appetite. All this made a great change in him, he worked about the house, and this of course made his grandmother better natured. She really cared a good deal for the tall youth; but regretted his inaction, and therefore scolded him often. One day he asked her for a bow, and she was delighted that he at last was taking an interest in the work of the men-folk. "Now let me see, she said, "your uncle's old bow used to hang up the ladder in the rear summer-room; it was a good one. Run and get it." The youth found it there, and beside it an old quiver and arrows which were featherless. He looked about and discovered some old shells in a plume-box, and with these he paid a man who knew how to plume arrows with eagle feathers. When everything was ready, he bade his grandmother good-bye and departed. Now, this young man was good-natured even though he had been greedy, and as he went along he met a ragged-skinned old Coyote who barked and yelped at him; he neither shot at it nor abused it, or anything of the kind; but he just jogged along and wondered what a fellow ought to do when out hunting. He had never learned anything, as he had been too lazy to trouble himself until now. Well, along he trudged, through the thin snow which had lately fallen, until he came to the base of the cliffs, where he struck the trail of some rabbits. He followed the trail into the thickets, and there he saw some bigger tracks. He went crashing through the bushes, and presently he saw a couple of dingy little coyote cubs sneaking into a hole under the rocks. "Ha!" thought he, "I never ate any of these things, and of what use would they be to me?" So he did not kill them, as many other men would have done. Turning around to retrace his footsteps, he saw the same old Coyote he had met before, trotting toward him. The old one came quite near; then he sat down, ducked his head two or three times and grinned. The youth stood stock still and looked at the Coyote; the Coyote sat still and looked at the young man. The youth exclaimed "Uh!" "Quite so!" said the Coyote. "How is it with you, bungler?" "Hey," said the youth. "Can you speak?" "Well, yes," said the Coyote. "Why didn't you shoot at me and call me names this morning?" "I — I don't know," stammered the youth. "You might at least have killed my cubs, why didn't you?" "Why should I kill them?" said the boy. "Why, indeed?" replied the Coyote. "Only men never stop to think of that. Do you know me?" "No," said the young man. "Well, I know you very well. You're a good sort of a fellow, even if you are a bungler, so come along to my house, and I'll teach you many things you need to know." "Very well," said the youth, but he thought to himself that it was certainly a queer thing, a Coyote talking and telling about his house. Just then the Coyote ran back a few steps, went around a rock and reappeared with an enormous back-load of rabbits. He led the way to a hole under a big rock, and there sat the two little cubs. At first sight they started forth to meet their father, but seeing the big young man, they whisked into the hole like the snap of a twig. "Hold on, you silly furlings," said the old Coyote, "take down my load, it's light. Do not be afraid of your uncle. Now if he had stuck one of his sharp sticks into your skins you might have had reason to run, but he didn't do anything of the kind." When they came to the hole the Coyote stopped, and said, — "Step in, my friend." "Where?" asked the youth. "Why, into my house; where else? Don't you see?" "Where?" asked the boy again. "I see nothing but a hole not as big as my two legs, let alone the rest of me." "Ha, ha!" laughed the Coyote. "Well, that is my house; step in, I say." But still the young man stood there. The Coyote reached up and nipped him just a little. This made the young man jump, and plump, into the hole slid one of his feet! The earth rumbled and there was a great big passage with a stout door at the end. The Coyote shouted, . — "Hai! Let us in!" "Yes, all right," said a soft voice from below, and the door opened, and there stood a fine little mother. "Come in," said she to the youth and the Coyote. In they stepped. There was a large room and everything one could wish for. Soft blankets and mantles, and bowls of steaming food. "Did luck meet you, old one?" asked the little woman. "O, half way," replied the Coyote as he stretched himself, shook himself and gave a jump when rip, went his skin, and there stood a splendid little old man before the astonished youth! "Well," said the Coyote Being, "that's the way we live down here; now make yourself at home." Then taking up the skin he hung it on an antler with several others. The little mother took a great bowl of stew from the fire, and piled enough baskets full of héwe or paper-bread, for a council. She threw down some blankets, and coaxing the two little ones out of their hiding place, bade all sit and eat. At first the young man was rather afraid, but the little old man was so merry, the broth smelt so rich and the héwe looked so flaky and sweet, that he soon fell to and ate more than all the rest put together. "Now," said the Coyote after they had finished, "I'll tell you how I know you. Your uncle was a friend of mine, and as he offered up many prayer-plumes to the Prey Beings, being poor like you, I took pity on him and taught him to hunt. That's his bow you are carrying; I recognized it at once. Well, no one ever taught you how to hunt, or how to gain the favor of my brothers and myself. Listen! We are the Masters of Prey throughout the six regions of the world of daylight. All we ask in return for helping the children of men is constant presents of prayer-plumes, for by them we live from age to age. Go, therefore, and prepare feather offerings for us all. I will help you, if you are faithful." The poor young man breathed his thanks on the hands of the little old man and his wife, and taking up his old quiver and bow, turned to go, when the little old man stopped him. "Here," said he, as he gave a string of rabbits to the youth, "this will make your old grandmother good-humored, and she'll help you gather plumes." Again the youth breathed on their hands, and set forth. It began to grow dark and he quickened his pace, until the lights of his village shone out before him. "Draw me in," he called out to his grandmother when he reached the house-top. And how delighted she was when she saw the rabbits. "Luck has met you today," she said, "but you must learn to make plumes and place them where the Prey Beings will find them." And she showed him how plume offerings should be made, and she taught him the ancient prayers to the Beasts and Prey Beings. All the next day he worked away at the prayer-sticks, and the next, and by the third day he had finished. Early the following morning he started out with the large bundle of sacred offerings and the weapons he carried before. Not long after he met the ragged old Coyote. "Ha, you come!" said he. "Yes," said the youth, "and I bring you the best prayer-plumes I could make." "It is well," said the Being, and up they climbed to the hole under the rocks. No sooner had they entered, than many coyotes came in, and shifting their skins, appeared like young warriors. The youth began to mistrust that they were not Prey Beings but Gods; and he gave them his offerings which they accepted, and breathed blessings of thanks upon him. They then put on their skins and departed, and the old Coyote said, "Now for the hunt!" Leaving his home under the rocks, they followed a crooked trail which took them to the southern mesas, and over these, down into the shadowy evergreen forests in the wide valleys beyond. And on the bottom of the very first valley they struck deer trails made in the melting snow. "Here," said the old Coyote, "it is your business now to look at this track. It was made by the leader. You can tell that by the way it is chipped into by the footprints of those that follow him. We will track this particular trail together. See now, the holes this leader's feet made in the snow are a little melted at the edges. That shows he has been gone some time; but by and by they will be sharper, and then you must step as though you were walking on grass-stalks and wished not to break them, for the deer will be listening behind some bushes or knoll in the valley. I will leave you at that time, and you must follow the trail until you come to where the straws are not yet straightened up in the bottom of the tracks. Then sit down and sing a prayer-song, and the deer will be listening behind some bushes or knoll in the valley. Now, when he hears your music, he will be charmed by it and hesitate. That will give me time, you see, to run around to the head of the valley before he gets there; for 'deer going home travel in cañons as men do in pathways.'" First swiftly, then more and more slowly, they followed the trail of the deer. When they came to a spot midway up the valley, where the trail began to look fresher, the Coyote suddenly darted off to one side and disappeared among the piñons. The youth had gone but little farther when, as the Coyote had said, he found not a grass blade erect in the footprints. Stealing silently along, he thought he heard a sound not far ahead, so crouching down he sang, — "Deer,

deer!

Your footprints I see, and I following come Over the mesas and through the deep cañons, Carrying prayer-plumes, — offerings sacred. Tarry I pray you, As my wild brother, I bring you offerings. Tarry I pray!" The deer was not far away, and when he heard the song he was greatly pleased; but never-the-less he whirled about, and, stamping the ground, led his followers, the does, fawns and short-horns, into the shelter of a cedar grove. He then turned and ran alone up the valley, but soon stopped to listen, for the youth was again singing the song of promise. "Who is this that brings me plume offerings?" thought the deer, and he traveled more slowly, but no sooner had he caught sight of his pursuer than he started forward at full speed. Now not far ahead was a side cañon, and there, behind a sage bush, lay the old Coyote, and swift as the little end of a snapped twig, he sprang up in the deer's pathway. With a loud snort the deer turned, only 'to be met by the approaching youth, toward whom he lowered his antlers. Noiselessly the Coyote stole up behind, and with a short, shrill bark bit the haunch of the frightened deer. Now the young man, scarce knowing what he did, drew his arrow to the tip and let it fly with the full strength of the long, tightened bow; and with a leap and a plunge, and a sidewise motion like a thick tree in the breath of a wind-storm, the monstrous stag tottered and fell. Then the youth sprang forward and repeated the hunter-prayers that his old grandmother had taught him. "Ha! my child," joyfully called the Coyote, "you are a lucky hunter! This day your winning is great, for you have entered a new trail of life, and the Beings of Game are your friends forever. A mighty hunter you will be, for you remembered the way of well-doing." And the old Coyote taught him how to skin and dress the deer, and how to wrap it up in its own hide for carrying; and then they made their way to the home of the Coyote. After he had changed his form, and they had feasted and smoked, the youth turned to his teacher, and said, — "O, father! I owe you much this day, and it is right that I offer you our slain animal, my thanks and my poor prayers. "No, my child, only a small portion will I take. Carry home the deer and its skin to your grandmother. A maiden, the daughter of the chief-priest of Pínawa, will see you from her house-top, and say, — `So you come!' Her you will marry, and you will be precious to your people." And the Coyote-man laid his hands on the shoulders of the young man and blessed him, and bade him "Be happy!" The youth then lifted his bundle to his shoulders and silently stepped through the doorway, which, as he passed it, rumbled, closed, and left him alone in the sunset shadows of the cliff. |