| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

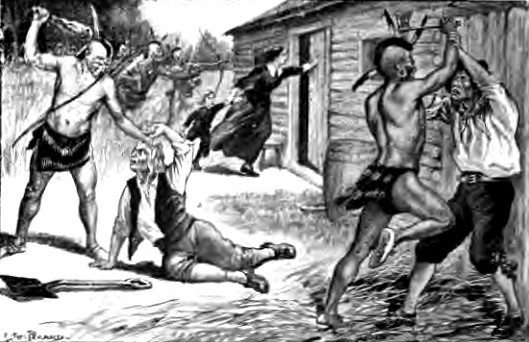

VIII. KING PHILIP'S WAR.

THE Indians had obtained from the French traders a supply of firearms and ammunition, and had learned with surprising readiness to . use them. It is thought that the possession of these arms excited and emboldened them to the acts of hostility which culminated, June 24, 1675, in the breaking out of the great King Philip's War, a war in which Indian revenge and rapacity were both fearfully displayed. The war started in Plymouth, and within twenty days "the fire began to kindle in these easterly parts, though distant two hundred and fifty miles." There were then nearly seven thousand English settlers in Maine, and between two and three times as many Indians. It is easy to see how great were the peril and distress of the pioneers when the long-smoldering hatred and revenge of the savages at last broke out. Squando, sagamore of the Sokokis, was a seer and a magician in the eyes of the Indians. He had counseled a peaceful policy toward the white men, although he declared that God himself had told him that the English people must be destroyed by the Indians. He had a prudent mind, for an Indian, and if it had not been for a great wrong which he suffered just as the news came of the Plymouth hostilities, he might have cast his influence for peace instead of war. Squando's squaw was paddling along the Saco in a canoe, with her baby, when some rough sailors in a boat, thinking it would be fine fun to discover whether papooses could swim like ducks, as the tradition ran, upset the canoe. The papoose sunk. The squaw dived, and brought it up alive, but it died within a few days, doubtless from the shock. Then Squando, who had unlimited power over his own tribe, and great influence over many others, used it all to arouse the Indians to fiercest warfare.  Wonolancet, Passaconaway's son, followed his father's counsel and took no part in the war. He was now chief of the Penacooks, a fierce and warlike tribe. He would not take sides with the enemy of his people, but "withdrew into the heart of the distant desert,"—supposed to be the forest near Mount Agamenticus. And so great was his influence over the stormy spirits of his tribe that most of them followed him. The Indians were especially bitter against the English colonists, because they refused to sell them arms and ammunition, which they had now come to depend upon in the hunting that was their chief means of subsistence, while the French, they said, were "free and cheerful" to supply them with whatever they needed. They believed, too, that the Great Spirit had given them for their own the country of their birth, and that they had absolute right in it; and they cherished and rehearsed, with a true Indian spirit of revenge, the old stories of kidnaping and cheating and general treachery on the part of the English. A committee of war was appointed by the General Court, intrusted with military power over the eastern parts, and with directions to furnish themselves with all necessary munitions of war for the common defense, and to sell neither gun, knife, powder, nor lead to any other Indians than those whose friendship was fully known. It was proposed to take from the Indians, as far as possible, their arms and ammunition. Some of the Canibas and Anasagunticook tribes peaceably gave up their weapons; but one Canibas Indian, named Sowen, turned with sudden fury upon Hosea Mallet, one of the party that received the arms, and would have killed him if he had not been seized and bound. The Indians confessed that Sowen deserved death, yet pleaded for his release. They offered forty fine beaver skins as a ransom, and hostages for his future good behavior.  Sowen was released, the Indians were feasted and given a plentiful supply of tobacco, always their hearts' desire, and Robinhood, sagamore of the Canabas, gave a great dance, the next day, celebrating the peace with a wild carousal. Squando, who took the warpath on account of the death of his papoose, appears now in a more honorable light, being the rescuer of Elizabeth Wakeley, a girl of eleven years, who had been carried into captivity by the Indians. The savages had previously killed with shocking cruelty all the rest of her family, except two little children, who were carried off in another direction. The Indians, having now tasted blood, seemed like wild beasts in their fury. They robbed and murdered in every defenseless settlement, and no one's life or possessions were safe. The dwelling houses of John Bonython and Major William Phillips were on opposite banks of the river, and both had been fairly well fortified. A friendly Sokokis native came to Bonython's house, and told him that a strange Indian, from the westward, with a party of Anasagunticooks, had been at his wigwam, persuading all his tribe to raise the tomahawk against the white people; that they had gone to the east, and would soon come back with many more Indians. Bonython, much alarmed, spread the news, and then took shelter, with the other settlers and their families, in Major Phillips's house, which was better garrisoned than any other. Next day they saw Bonython's house in flames, and a sentinel caught sight of an Indian lurking under the fence. Phillips, at his window, was wounded by an Indian's gun, and those who lay in ambush near the house thought him killed, and with savage shouts exposed themselves to sight. The settlers fired upon them from the house and from outposts in all directions. Several Indians were wounded, including the leader, who died while they were on the retreat. The assailants were finally convinced that the place could be taken only by stratagem. To draw the men out of the fortification, they set fire to a small house, and afterwards to the mill, calling to the settlers: "Come, now, you English coward dogs! Come put out the fire, if you dare!" This move proving unsuccessful, they resumed their firing, and continued it until the moon set, about four in the morning. Then the savages, taking a cart, hastily constructed a battery upon the axletree and forks of the spear, forward of the wheels, to shelter them from the musketry of the fort, and filled the body of the cart with birch rinds, straw, and matches. This engine they ran backward, within pistol shot of the garrison house, intending to communicate to it, by means of long poles, the flaming combustibles. But in passing a small gutter one wheel stuck fast in the mud, which gave a sudden turn to the cart, exposing the whole party to a fatal fire from the right flanker,—an opportunity which the settlers quickly improved. Six Indians fell dead. Fifteen, in all, were wounded in the assault; and the survivors, about sixty in number, tired of the attack, and mortified at the repulse, withdrew. During the siege there were fifty persons in the house, of whom only ten were effective men; five others could only partially assist; and one or two, besides Major Phillips, were wounded. No aid could be spared to Major Phillips, and he was forced to leave his house, which the infuriated Indians burned to the ground. They burned all the houses above Winter Harbor, and shot down in cold blood all the white travelers whom they encountered. They carried into captivity from Winter Harbor a Mrs. Hitchcock, and the next spring, when a ransom was offered for her return, they reported that she had died, in the winter, from eating poisonous roots which she had mistaken for groundnuts. Instances of heroism that thrill the blood are not rare in the records of those dreadful days, when even old men and feeble women, holding their lives in their hands, sold them dearly in defense of their loved ones. The story is told of a young heroine at Newichawannock (South Berwick), whose name, unfortunately, has been forgotten. The house of John Tozier was in an isolated region, and Tozier himself, and the few other men of the neighborhood, had gone to the relief of the people of Saco, who were surrounded by Indians. The fifteen persons left wholly unprotected in Tozier's house were all women and children. An attack was made upon the house, led by two of the fiercest warriors of their tribes, one of whom was Andrew, a Sokokis brave, and subject of the great Squando, in whose character cruelty and kindness seem to have been incomprehensibly combined. It was a young girl of eighteen who discovered the approach of the dreaded Indians, and she shut the door and held it fast, parleying with them to gain time and allow the rest of the household to escape. When finally the Indians cut the door down with their hatchets, they found that all but her had gone.  The exasperated savages fell upon her with their hatchets, and left her for dead. They then pursued the fleeing family, and overtook two of the children. A little three year-old, who was too young to travel, and likely to be an incumbrance, they killed, and the older child they carried into captivity. It is pleasant to be able to add to this tale of horror that the brave girl revived after her fiendish assailants had gone, crawled to the garrison for relief, was healed of her wounds, and lived to tell, in peaceful days, the story to her children. The Indians went on burning and pillaging and slaughtering, until a temporary lull in hostilities was effected by the chief magistrate of the Pemaquid plantation, Abraham Shurt, whose fame has come down to us as a man of peace and of unusual good sense. He succeeded in inducing the warlike sagamores to meet him at Pemaquid for a parley. The result was a truce, by which they engaged to live in peace with the English, and to prevent, if possible, the Anasagunticooks from committing any more depredations. Much faith was felt in these pacific measures, and the General Court ordered that quite a large sum should be taken from the public treasury for the relief of those friendly Indians whose wigwams had been burned and whose harvests had been trampled down. But this truce was narrow in its province, and had but slight effect. In other parts of the colony a different policy prevailed. The Indians, having set out upon the warpath, were not easily turned back, and many of the English believed in a policy of extermination rather than of peace. The town of Berwick seems to have been chosen by the Indians for their fiercest onslaughts, in spite of the fact that one of the strongest of the garrison houses was located there. In October, 1675, a party of a hundred Indians, partly of the Sokokis tribe (always known as the fiercest) and partly of the Canibas, attacked Richard Tozier's house, burned it to the ground, killed Tozier, and carried his son away captive. This was in sight of the garrison house. Lieutenant Roger Plaisted, in command of the garrison, sent a little company of nine picked men to watch the enemy's movements. The men were unwary, and walked into an Indian ambuscade. The instinct of war born in the Indians seems to have been entirely lacking to the English settlers. For a hundred years the English officers went on leading their men into the snares that the wily savages set for them, and it is said that even the squaws made merry over their stupidity. Plaisted knew that a hundred cunning savages were lurking about, and yet he led his men boldly into the midst of them. Three of the nine were killed at once; the others succeeded in making their escape. The next day Plaisted sent a team with twenty armed men to bring in the bodies of the slain. They had a cart drawn by oxen, and Plaisted himself led the little company. They had placed one dead body in the cart, when, from the bushes behind a stone wall, a hundred and fifty Indians poured upon them a deadly fire. Only a few of the men escaped. Lieutenant Plaisted fought bravely until cut down by a tomahawk. Two of his sons were among the killed. In view of the Berwick highway may still be seen a monument with this inscription: "Near this place lies buried the body of Roger Plaisted, who was killed by the Indians October 16, 1675, aged 48 years; also the body of his son, Roger Plaisted, who was killed at the same time." A quick-witted stratagem saved the house of Captain Frost at Sturgeon Creek, where this same band of In. dians proceeded from Berwick. Captain Frost was outside his door, and had ten shots fired at him, harmlessly, before he had time to close it upon the Indians. There were only three boys with him in the house, yet he had the presence of mind to shout out commands as if there were a body of soldiers within. "Load quick! Fire, there! That's well! Brave men!" he shouted. And the Indians, doubtless unsuspicious of cunning in the settlers, where they seldom found it, concluded that the soldiers here were too many for them, and rapidly retreated. In the settlements between Piscataqua and Kennebec, within the short space of three months, there were eighty lives lost, with a great number of dwelling houses and other property. All business was suspended, harvests were ungathered, and homes deserted. Men, women, and children were huddled in small garrisons, or in the larger houses, which had been as strongly fortified as possible. 'As winter came on there was a revival of the hope of peace. The Indians had no provisions on hand, nor any means to buy them. Their ammunition was consumed, the snow was too deep for hunting, and they saw that peace or starvation was the alternative before them. The sagamores, therefore, requested an armistice for the whole body of Indians eastward, promising to be the submissive subjects of the government, and to surrender all captives without ransom. Many of those carried into captivity were from time to time restored, and doubtless welcomed by their friends as if they had arisen from the dead. Through seven months there was peace, and that the war broke out again was not wholly due to the savages. There were influences of private gain and personal revenge; and the suspicions of the settlers against the Indians were, not unnaturally, but sometimes unfortunately, never sleeping. Several Indians were seized by kidnapers and carried off in vessels and sold as slaves in foreign countries. Some of the kidnaped Indians were Micmacs from Nova Scotia, and the Micmacs were thus led to join the Maine tribes in their warfare. A council was held at Teconnet, near what is now Waterville. It has been thought that if Squando had been present the treaty might have been effected; for although Squando's moods were variable, he was known to have at that time a strong desire for peace. Madockawando, the chief who was the ruling spirit of the five sagamores present, was angry at the distrust shown by the settlers in not consenting to sell ammunition to the Indians; and the council broke up without result. King Philip was killed in August, 1676, but that did not terminate the war. The Indians, who called him Metacom, reverenced him as of almost superhuman power, and they believed that through his influence, even after he had gone to the "happy hunting grounds," leaders would be raised up to guide them to victory. Squando now came to the front with fresh revelations and prophecies. He pretended that God appeared to him in the form of a tall man in black clothes, commanding him to leave his drinking of strong liquors, and to pray, and to keep Sabbaths, and to go to hear the Word preached; all which things the Indian did for some years, with great apparent devotion. Squando assumed supernatural gifts and powers, but neither he nor any of the other great chiefs ever took upon themselves such earthly state as did King Philip. When an ambassador was sent to him from the governor of Massachusetts to inquire why he was making preparations for war, the Indian haughtily answered: "Your governor is but a subject of King Charles of England. I shall not treat with a subject; I shall treat only with the king, my brother. When he comes, I am ready." Proud King Philip was dead, and his forces were scattered; but many of his warriors joined the Maine Indians, and the ravages there were continued with renewed force. Squando was assured by supernatural visitants that the destruction of the English would now be soon completed. |