| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

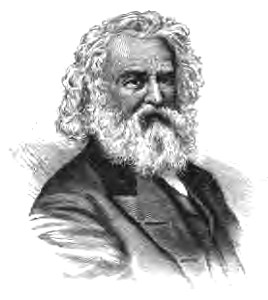

XXV. MAINE'S FAMOUS HUMORIST.

MAINE'S distinguished sons are the distinguished sons of the nation; their names are known to every boy and girl in the country. Hamlin, Fessenden, Morrill, Washburn, Clifford, Hale, Frye, Reed, Milliken, and Boutelle,—every one in the country knows enough of their history to know that Maine claims them; Chief Justice Fuller, too, and Naval Secretary Long. That General O. O. Howard, the military hero, is a son of Maine has been published far and wide, and that Blaine adopted the state as his home and reflected upon her all the glory of his mature years. And who does not know her roll of celebrated authors—Longfellow, the Abbotts, Miss Jewett, Mrs. Spofford, and many others whose names occur to every one? She claims even Hawthorne as a graduate of Bowdoin College and a sometime resident, and we have all been told that Mrs. Stowe wrote "Uncle Tom's Cabin" under the shadow of Bowdoin's walls.  O. O. Howard But with her long roll of honor—to which are added sculptors and painters of noble repute—Maine has almost forgotten, or has allowed others to forget, her claim to the greatest wit of his time, "Artemus Ward." His genuine and spontaneous humor savored richly of the Maine soil, and yet, strangely, it found its highest appreciation in England. At home, in Maine, they seemed always a little chary of acknowledging how funny Artemus really was. A quick wit is a common inheritance, even in far-away rural regions of Maine. The deacon who beats all the "city fellows" at checkers has also a quaint and droll crispness of speech which his serious views of life are allowed to modify only on serious occasions. And the reckless, loitering urchin, who knows where the trout bite better than he knows the way to school, will astonish you with keen views on important points and with the incisive wit with which he expresses them.  Longfellow There is undoubtedly only one Artemus, but he may have been, nevertheless, only the consummate development of a type familiar at home and consequently less highly valued there than abroad. Moreover, his humor depended somewhat upon bad spelling, a sort of wit which degenerates so easily into vapidity or coarseness that it is not apt to be highly considered. But Artemus Ward's wit never degenerated; it was such spontaneous, bubbling fun that the spelling struck one as quite natural and inevitable. His first lecture in England was delivered in the Egyptian Hall to a large and enthusiastic audience. The heat was very great when he appeared, as he wrote, for the first time in England, "be4 a C of upturned faces;" it was so oppressive to a man in his state of health that he felt constrained to remark, "When the Egyptians built this hall I wish they had not forgotten the ventilation." His English visit was a great success, but he closed it and his life together at the early age of thirty-two, followed by the sincere regret of friends and admirers in all walks of life. He flashed like a brilliant meteor across the sky of American literature, emerging from obscurity, having a brief but brilliant career, and then vanishing. His cometlike career induced questions as to his history. People wanted to know something about the gifted American who had so entertained them by his spontaneous and original humor. His extraordinary devotion to his aged mother added a romantic interest to his personality. He loved money, only for her sake; in his utter devotion to her he was willing to sacrifice any taste or ambition. Charles Farrar Browne was born at Waterford, Maine, in 1836. He early left home to seek his fortune, and the first employment at which he tried his hand was setting type on the "Carpet Bag," a comic paper published at Chelsea, Massachusetts. The "Carpet Bag" has been chiefly known to fame as the vehicle for the funny sayings of "Mrs. Partington" (B. P. Shillaber). At the time when "Charley Browne" began his work as compositor, Seba Smith, another Maine humorist, was its editor.  Artemus Ward After he had set up the "Carpet Bag" jokes for a while, young Browne essayed one upon his own account. He disguised his writing and offered it as an anonymous contribution. The editor of the "Carpet Bag" knew a joke when he saw one, and the young compositor set it up the next day for publication. He removed, soon after, to the little town of Tiffin, Ohio, where he found an opportunity as a reporter as well as compositor. But there either his roving disposition declared itself or he wished to be rid of typesetting. He migrated to Toledo, where he abandoned his trade and became a fully fledged reporter. His forte showed itself, at once, as humorous satire, and before long his witty and caustic paragraphs in the Toledo "Commercial" attracted attention, which led, in 1858, to an invitation to the staff of the Cleveland "Plaindealer." He was then but twenty-three years old. He had, until then, used no distinctive signature, but he adopted the nom de plume of "Artemus Ward, Traveling Showman from Baldwinsville, Injianny." He advertised his show as comprising, among other interesting objects, "3 moral Bares, a Kangaroo ('twould make you laff yourself to deth to see the little cuss jump up and squeal), wax figgers of Genl. Washington, Capt. Kidd, Genl. Taylor, Dr. Webster, and other celebrated piruts and murderers." In this style he was unique, and the great army of his imitators seem only toilsome laborers who never succeed in manufacturing anything that approaches his fresh fun. "He can scarcely be said to have had any models," says Mr. Northcroft, "although Artemus himself declared that in the beginning Seba Smith's work served him to some extent as a pattern." "Some kind person has sent me Chawcer's poems," writes Artemus. "Mr. C. had talent, but he couldn't spel. It is a pity that Chawcer, who had geneyus, was so unedicated." We find, soon afterwards, that he has gone to New York city and is editing "Vanity Fair," the American "Punch." But it is from the "Plaindealer" that his success may be dated. His nomadic nature asserted itself, and editorial duties were an irksome round. He planned a lecturing tour with the then fashionable panorama as an adjunct. Finding that his finances would scarcely warrant his investing in an expensive panorama, he bought a poor and cheap one, and announced on his program: "The panorama illustrating Mr. Ward's lecture is rather worse than panoramas usually are." On appearing before his audience he would gravely announce his subject, then tell what he called a little story, which, with jokes, would last about an hour and a half. He would then gravely remark, "I now come to my subject." Pulling out his watch with apparent embarrassment, he would say, "But I have exceeded my time!" and would dismiss his audience with a confusion which seemed absolutely genuine. There were always a few grave faces, people who could not or would not see the point of his jokes; so he inserted in his program this notice: "Mr. Ward will call on the citizens of London, at their residences, and explain any jokes in his narrative which they may not understand." While in England he wrote a series of letters to "Punch," which are among his best efforts. He had been very severe upon the Mormons, and he went among them to lecture, feeling some doubt as to his reception. But on his return he announced that the Mormons were not such "unprincipled retches" as he had described. "Their religion is singular," he said, "but their wives are plural. Brigham Young is an indulgent father and a numerous husband. He is the most married man that I ever saw." The showman's free-and-easy fun is never coarse or irreverent of sacred things. He says himself, "I rarely stain my pages with even mild profanity. It is wicked, in the first place, and not funny, in the second." The London "Times " said: "His humor is utterly free from offense. Not only are his jokes irresistible, but his shrewd remarks prove him a man of reflection as well as a consummate humorist." No man had more real reverence than the mocking showman, or greater fineness and delicacy of sentiment, as is shown by his devotion to his mother. What he said in his deliciously funny interview with Prince Napoleon was quite seriously true: he "bleeved in morality, likewise in meet'n'-houses." These are the reasons he gives for asking personal questions about the emperor. "I want to know how he stands as a man. I know he's smart. He's cunnin', he's long-headed, he is grate. But onless he is good he'll come down with a crash, one of these days; and the Bonypartes will be busted up ag'in! Bet yer life." Thoroughly characteristic of his effortless wit is the story of his appearance before his wife after some supposed great change in his looks. "'Maria, do you know me?' I asked," says Artemus. "You old fool, of course I do!' answers Maria, crisply. I perceived at once that she did." He died of consumption when he was but thirty-two, regretted and beloved, as his friend Robertson says, by all who knew him. In the record office at Paris, the shire town of Oxford county, Maine, is the will of Artemus Ward, made in England just before his death. It was in some respects a "goak," and is pathetic because it shows signs of being a forced one, the first of that kind of which its author was ever guilty. It is inscribed on two heavy sheets of parchment, about two feet square, in old English text, decorated with capitals and flourishes that it must have taken hours to fashion. The instrument begins: "This is the will of me, Charles Farrar Browne, known as Artemus Ward." The testator directs that his body be buried in Waterford lower village, and bequeaths his library to the best scholar in Waterford upper village, and his manuscripts to R. H. Stoddard and Charles Dawson Shanley. After a few minor bequests to his mother and other relatives he gives the balance of his property, which he intimates is considerable, to found an asylum for worn-out printers. Horace Greeley is to be sole trustee, and his receipt is to be the only security demanded of him. The printer's asylum was a joke, as he knew that the property he left was scarcely sufficient to pay the minor bequests. The parchment was sent to the Oxford probate court in a tin box, secured by a padlock and stamped with the British coat of arms. He was of quaint appearance, having a long, lank figure and rugged features. He always wrote his jokes sitting with his long legs hooked up on the arms of his office chair, and generally in convulsions of laughter, although when he delivered himself of the jokes in public he was as grave as a judge. An old friend writes of him: "Charley's was a gentle and beautiful spirit. And I always think that just such wit as his could have blossomed nowhere but in Maine." "It is better not to know so much," says the showman, "than to know so many things that ain't so!" |