| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2012 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| VII

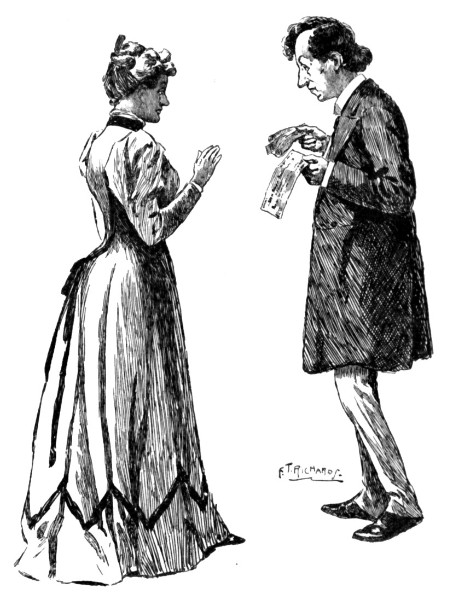

A NEW boarder had joined the circle about Mrs. Pedagog's breakfast-table. He had what the Idiot called a three-ply name — which was Richard Henderson Warren — and he was by profession a poet. Whether it was this that made it necessary for him to board or not, the rewards of the muse being rather slender, was known only to himself, and he showed no disposition to enlighten his fellow-boarders on the subject. His success as a poet Mrs. Pedagog found it hard to gauge; for while the postman left almost daily numerous letters, the envelopes of which showed that they came from the various periodicals of the day, it was never exactly clear whether or not the missives contained remittances or rejected manuscripts, though the fact that Mr. Warren was the only boarder in the house who had requested to have a wastebasket added to the furniture of his room seemed to indicate that they contained the latter. To this request Mrs. Pedagog had gladly acceded, because she had a notion that therein at some time or another would be found a clew to the new boarder's past history — or possibly some evidence of such duplicity as the good lady suspected he might be guilty of. She had read that Byron was profligate, and that Poe was addicted to drink, and she was impressed with the idea that poets generally were bad men, and she regarded the waste-basket as a possible means of protecting herself against any such idiosyncrasies of her new-found genius as would operate to her disadvantage if not looked after in time. This waste-basket she made it her daily duty to empty, and in the privacy of her own room. Half finished "ballads, songs, and snatches" she perused before consigning them to the flames or to the large jute bag in the cellar, for which the ragman called two or three times a year. Once Mrs. Pedagog's heart almost stopped beating when she found at the bottom of the basket a printed slip beginning, "The Editor regrets that the enclosed lines are unavailable," and closing with about thirteen reasons, any one or all of which might have been the main cause of the poet's disappointment. Had it not been for the kindly clause in the printed slip that insinuated in graceful terms that this rejection did not imply a lack of literary merit in the contribution itself, the good lady, knowing well that there was even less money to be made from rejected than from accepted poetry, would have been inclined to request the poet to vacate the premises. The very next day, however, she was glad she had not requested the resignation of the poet from the laureateship of her house; for the same basket gave forth another printed slip from another editor, begging the poet to accept the enclosed check, with thanks for his contribution, and asking him to deposit it as soon as practicable — which was pleasing enough, since it implied that the poet was the possessor of a bank account. Now Mrs. Pedagog was consumed with curiosity to know for how large a sum the check called — which desire was gratified a few days later, when the inspired boarder paid his week's bill with three one-dollar bills and a check, signed by a well-known publisher, for two dollars. By the boarders themselves the poet was regarded with much interest. The School-Master had read one or two of his effusions in the Fireside Corner of the journal he received weekly from his home up in New England — effusions which showed no little merit, as well as indicating that Mr. Warren wrote for a literary syndicate; Mr. White-choker had known of him as the young man who was to have written a Christmas carol for his Sunday-school a year before, and who had finished and presented the manuscript shortly after New-Year's day; while to the Idiot, Mr. Warren's name was familiar as that of a frequent contributor to the funny papers of the day. "I was very much amused by your poem in the last number of the Observer, Mr. Warren," said the Idiot, as they sat down to breakfast together. "Were you, indeed?" returned Mr. Warren. "I am sorry to hear that, for it was intended to be a serious effort." "Of course it was, Mr. Warren, and so it appeared," said the School-Master, with an indignant glance at the Idiot. "It was a very dignified and stately bit of work, and I must congratulate you upon it."  THE INSPIRED BOARDER PAID HIS BILL "I didn't mean to give offence," said the Idiot. "I've read so much of yours that was purely humorous that I believe I'd laugh at a dirge if you should write one; but I really thought your lines in the Observer were a burlesque. You had the same thought that Rossetti expresses in 'The Woodspurge':

'The

wind flapped loose, the wind was still,

Shaken out dead from tree to hill; I had walked on at the wind's will, I sat now, for the wind was still.' That's Rossetti, if you remember. Slightly suggestive of 'Blow Ye Winds of the Morning! Blow! Blow! Blow!' but more or less pleasing." "I recall the poem you speak of," said Warren, with dignity; "but the true poet, sir — and I hope I have some claim to be considered as such — never so far forgets himself as to burlesque his masters." "Well, I don't know what to call it, then, when a poet takes the same thought that has previously been used by his masters and makes a funny poem — " "But," returned the Poet, warmly, "it was not a funny poem." "It made me laugh," retorted the Idiot, "and that is more than half the professedly funny poems we get nowadays can do. Therefore I say it was a funny poem, and I don't see how you can deny that it was a burlesque of Rossetti." "Well, I do deny it in toto." "I don't know anything about denying it in toto," rejoined the Idiot, "but I'd deny it in print if I were you. I know plenty of people who think it was a burlesque, and I overheard one man say — he is a Rossetti crank — that you ought to be ashamed of yourself for writing it." "There is no use of discussing the matter further," said the Poet. "I am innocent of any such intent as you have ascribed to me, and if people say I have burlesqued Rossetti they say what is not true." "Did you ever read that little poem of Swinburne's called 'The Boy at the Gate'?" asked the Idiot, to change the subject. "I have no recollection of it," said the Poet, shortly. "The name sounds familiar," put in Mr. Whitechoker, anxious not to be left out of a literary discussion. "I have read it, but I forget just how it goes," vouchsafed the School-Master, forgetting for a moment the Robert Elsmere episode and its lesson. "It goes something like this," said the Idiot:

"Sombre

and sere the slim sycamore sighs;

Lushly the lithe leaves lie low o'er the land; Whistles the wind with its whisperings wise, Grewsomely gloomy and garishly grand. So doth the sycamore solemnly stand, Wearily watching in wondering wait; So it has stood for six centuries, and Still it is waiting the boy at the gate." "No; I never read the poem," said Mr. Whitechoker, "but I'd know it was Swinburne in a minute. He has such a command of alliterative language." "Yes," said the Poet, with an uneasy glance at the Idiot. "It is Swinburnian; but what was the poem about?" "The boy at the gate," said the Idiot. "The idea was that the sycamore was standing there for centuries waiting for the boy who never turns up." "It really is a beautiful thought," put in Mr. Whitechoker. "It is, I presume, an allegory to contrast faithful devotion and constancy with unfaithfulness and fickleness. Such thoughts occur only to the wholly gifted. It is only to the poetic temperament that the conception of such a thought can come coupled with the ability to voice it in fitting terms. There is a grandeur about the lines the Idiot has quoted that betrays the master-mind." "Very true," said the School-Master, "and I take this opportunity to say that I am most agreeably surprised in the Idiot. It is no small thing even to be able to repeat a poet's lines so carefully, and with so great lucidity, and so accurately, as I can testify that he has just done." "Don't be too pleased, Mr. Pedagog," said the Idiot, dryly. "I only wanted to show Mr. Warren that you and Mr. Whitechoker, mines of information though you are, have not as yet worked up a corner on knowledge to the exclusion of the rest of us." And with these words the Idiot left the table. "He is a queer fellow," said the School-Master. "He is full of pretence and hollowness, but he is sometimes almost brilliant." "What you say is very true," said Mr. Whitechoker. "I think he has just escaped being a smart man. I wish we could take him in hand, Mr. Pedagog, and make him more of a fellow than he is."  I KNOW YOU CAN'T, BECAUSE IT ISN'T THERE Later in the day the Poet met the Idiot on the stairs. "I say," he said, "I've looked all through Swinburne, and I can't find that poem." "I know you can't," returned the Idiot," because it isn't there. Swinburne never wrote it. It was a little thing of my own. I was only trying to get a rise out of Mr. Pedagog and his Reverence with it. You have frequently appeared impressed by the undoubtedly impressive manner of these two gentlemen. I wanted to show you what their opinions were worth." "Thank you," returned the Poet, with a smile. "Don't you want to go into partnership with me and write for the funny papers? It would be a splendid thing for me — your ideas are so original." "And I can see fun in everything, too," said the Idiot, thoughtfully. "Yes," returned the Poet. "Even in my serious poems." Which remark made the Idiot blush a little, but he soon recovered his composure and made a firm friend of the Poet. The first fruits of the partnership have not yet appeared, however. As for Messrs. Whitechoker and Pedagog, when they learned how they had been deceived, they were so indignant that they did not speak to the Idiot for a week. |