| THE

FURNISHING OF THE

HOME

WHEN

the home is built, it must be occupied. It is to be used, lived in,

made a part and expression of a family circle. First of all, it must

be furnished, and the taste and thought revealed in this task

determines in no small degree the character it will assume and

impress upon its occupants. It is therefore of the first importance

that the furnishing be done deliberately, step by step, piece by

piece, so that it becomes a growth and expression of the interests

and ideals of the family. The thoughts that I have endeavored to make

clear concerning the building of the home apply equally to its

furnishing. Simplicity, significance, utility, harmony — these are

the watchwords!

Although

the furnishment may better be a matter of deliberate growth rather

than of immediate completion, it by no means follows that the work

should be haphazard and without plan. On the contrary, just as the

painter in creating a picture may not know in advance all the details

and subtleties which he is to embody, but nevertheless has his

general composition and color scheme well in mind, so should he who

fits out a room consider in advance the underlying idea of tone and

form. The first object is to create an atmosphere. How often we enter

an apartment, full of elegant and beautiful things, in which there is

no continuity of idea, no central thought which dominates the place!

And when we come upon some simple room about which there is a sense

of rest and harmony, we do not always stop to analyze the effect to

see how it is produced. We feel that there is an intangible idea back

of all the detail, and it pleases us, although we know not why.

As a

rule it will be found that the harmony of an apartment is determined

by its color scheme. An illustration of a gross violation will serve

to enforce the point. If the window curtains were of so bizarre

and unassorted a character that upon each window hung a drapery of a

different color, some figured, some striped and others plain, even

the most unobservant eye would detect that the room looked absurdly

ill furnished. Upon the substitution, for this motley array of

curtains, of some warm, quiet fabric without ornamentation, an

appearance of harmony would at once seem dawning upon the room. But

if the walls were of white plaster or of some crude figured

wall-paper, the desired unity would be but dimly felt. What a change

is wrought by covering the entire wall-space with a good warm color,

either in harmony with or in judicious contrast to the curtains! It

is the background of the picture, the dominant note of the chord, the

underlying idea of the room, which needs only elaboration and accent

to produce a finished whole.

This

matter of color scheme is so fundamental to any successful results in

furnishing that it may be well to consider a little more in detail

what colors to use and what to avoid.

No

definite and final rules can be formulated on this subject, for in

the last analysis taste is the only guide. In general, however, I

should begin by excluding white. A large mass of white on the walls

makes a glare which is extremely fatiguing to the eyes. The light is

too diffused and is far more trying than a blaze of sunlight

streaming through a mass of windows. A similar effect may be noted

out of doors upon a hazy day when the sun is but thinly veiled behind

a white mist. On such occasions the glare is positively painful.

While a large mass of white is thus to be avoided for physiological

reasons, even a small spot of it will often be objectionable from an

artistic point of view. The eye as it ranges freely about the room is

unduly arrested by the bit of white which fails to fit into its

proper relation

with the whole.

How seldom does a painter venture to use untoned white in a picture,

and how carefully he leads up to it when he does introduce it! The

same principle applies to the color scheme of a room. A picture

surrounded by a white mat stands out of all relation to the

environing walls. Indeed, I should use white as part of a decorative

scheme only where the idea of great cleanliness needs emphasis, or in

making a human figure the culminating note in the home picture. A

white spread for the dinner table, setting off the glint of silver

and cut-glass or the color of patterned dishes, has an

appropriateness all its own, especially when the room is artificially

lighted. For breakfast and lunch, during the daylight hours, the bare

wood table, with dishes upon mats, always seems to me more

attractive.

Cottage

of Wood with Exterior Open Timber Work

The

next guiding thought,

although any such may have its exceptions, is that cold colors are to

be avoided and warm tones used instead. Pale blues, grays or greens

are not as a rule cheerful, while buff, brown and red, or

occasionally deep blue or rich green, are full of warmth and

brightness. It is always safe to be conservative in the background

color, and a neutral tone is therefore preferable to a color

aggressively pronounced.

It will

now be apparent

why a wood interior is so satisfactory. The color of the natural

wood, and especially of redwood, makes a warm, rich and yet

sufficiently neutral background for the furniture. Some of our

lighter woods, notably pine and cedar, may be stained or burned to a

dark tone as already specified in the preceding chapter, provided

that no glazed surface be put upon them with varnish or polish. A

slightly irregular texture. is more interesting on a wall than an

absolutely uniform finish. Natural wood with its varied graining is

one of the most charmingly modulated surfaces. Painted burlap glued

to the wall makes an attractive finish on account of its coarse,

irregular weave. Japanese grass-cloth has a similar interest, and is

very effective. in combination with gilding. I know of a plaster

ceiling painted with liquid gold which is beautifully harmonious and

elegant in combination with redwood paneled walls. Rough plaster may

be toned with calcimine to any appropriate shade, while smooth

plaster is better when covered with cartridge paper or with some

plain fabric.

Although

many architects of admirable taste may not agree, I venture to

suggest the elimination of figured wallpaper, and indeed of all

machine-figured work about the home. Most papers are undeniably bad;

a few are equally undeniably beautiful in design. But if the

contention for which I am standing has any weight — namely, that

ornament should be used with reserve and be studied for the

particular space it is to fill — then even an unquestionably good

wall-paper is inappropriate for three reasons, — because the

ornament is used too lavishly and indiscriminately, because it cannot

be turned out by machinery suited to the particular wall upon which

it is to be imposed, and, furthermore, because it detracts from any

ornament which may be put next it. A picture or a vase, for instance,

is never so effective when placed against a patterned background as

when surrounded by a plain tone of appropriate color.

But

enough of walls and surfaces! Let us assume that a good color has

been secured and in a soft, unobtrusive texture. Attention may next

be given to the draperies. Many people insist on window shades that

shoot up and down on rollers — smooth, opaque, characterless things

that give a stiffness and mechanical rigidity to the windows.

Curtains hung by brass rings upon rods are all — sufficient to cut

out the sun by day and to exclude the view of outsiders by night, and

they are far more graceful and soft in effect. The only difficulty is

to get material that will not fade when left in the steady glare of

the sun. All the so-called art — denims and burlaps with which I

have had experience are so badly dyed that a very short exposure

bleaches them beyond recognition, but the coarse dark blue Chinese

denim is very serviceable. The satin-finish burlap, undyed, is also

satisfactory on account of its permanence. Linen crash of an ecru

color, Japanese grass-cloth, and some coarse, simple ecru nets are

most effective. Curtains made of fine strips of bamboo lashed

together give a soft, pleasing light in the room, but do not

completely cut out the sun. They may be used to great advantage in

combination with some heavier material, such as colored ticking or

corduroy. Soft leather in the natural tan makes elegant and

substantial curtains, but is rather expensive. Pongee is good,

although, like all silks, it rots after long exposure to the sun.

In

addition to window curtains, portiéres are often useful draperies,

for giving privacy to an alcove, or between apartments where a door

is unnecessary. Oriental hangings, such as Bagdad curtains, if made

with the old dyes, are especially effective, but a plain chenille

curtain, or even one of such coarser material as burlap, is always

safe if its color harmonizes with the room. When hand-made Oriental

hangings cannot be afforded and some ornament is desired, a

conventional decoration in gold cord can be stitched to the border,

or a little color, preferably in dark rich tones, may be cautiously

added in embroidery or appliqué.

I

assume that the floor of our home be of natural wood, shellaced and

waxed, and afterwards polished with a friction brush. Cleanliness, if

not an aesthetic impulse, should prompt this. One or two fine

Oriental rugs — Bokbaras, Cashmeres, or Persians, for example —

made with the old dyes, are a great addition to any room, but a rag

carpet serves as a passable substitute. It will hardly be necessary

after all that has been said about machine ornament, to urge the

exclusion of all modern patterned rugs and carpets. These are

generally characterized by bard, set designs, mechanically precise,

made in crude colors that fade ere long to sorry-looking tones.

Better far is a piece of plain Brussels carpet of good color.

Having

attended to the background, and the window curtains, portiéres and

rugs in harmonizing tones, with here and there a note of accent or of

contrast, if this be skilfully managed, the atmosphere of the room is

established. It now remains to introduce the furniture. Much of this

can be built in to the special places designed for it. Still the

restraint in ornament should be kept steadily in mind. The first

essential of the furniture is good, simple design and thorough-going

workmanship, — no veneer, no paint or varnish, no decorations stuck

on to give the piece a finish, but plain, honest, straightforward

work!

The

kinds of furniture which most readily lend themselves to being built

permanently into the house are window- and fireplace-seats,

book-shelves, and sideboards. The seats can be made quite plain, and

if hinged serve the additional purpose of store chests. Book-shelves

call for little or no ornament, although the end boards may be

massive and carved if desired. There is much opportunity for making

the sideboard picturesque, with paneled or leaded-glass doors,

attached with ornamental strap hinges of wrought iron or hammered

brass. The arrangement of shelves and cupboards in a sideboard gives

great scope for effective design.

With

such pieces built in, and with a good tone to the rooms accented by

rugs, portiéres and curtains, the home begins to assume a furnished

aspect, and it is easy now to see what is needed and what will

harmonize. Furniture made to order by a cabinet-maker, or even by a

good carpenter, will be found of especial interest if simple models

are followed. In the furniture as in the house itself it is well to

emphasize the construction. Panels held together with double

dove-tailed blocks, joints secured with pegs, and tenons let through

mortises and held with wedges, are always evidences of good honest

workmanship.

As to

the design of such furniture, straight lines expressing the

construction and utility in the most natural manner are safest, and

only an experienced artist can safely deviate from such. There are a

few exceptions, however, which are not only justifiable but often

desirable. A round top for a dining-table is very pleasing on account

of the feeling of equality of all who sit about it. It seems in a way

more sociable than a table with a head and foot. A small square table

can be made with two or more round tops of different sizes which fit

down upon it, to be used as occasion requires. While a chair with

square legs is massive and dignified in effect, the rounded legs give

lightness and grace. A light and very inexpensive chair which might

well be in more general use in California is the simple form made

with strips of rawhide for a seat. It is a relic of the mission days,

I believe, and is thoroughly appropriate to the style of house we are

contemplating. Rush-bottom square-post chairs are substantial,

comfortable and most harmonious in the simple room. A chair with the

seat sloping backward and with the back at right angles to the seat

is more comfortable than one with the seat parallel to the floor,

which makes one sit bolt upright. Italian chairs carved of black

walnut have a grace and elegance that give a touch of luxury to the

most unpretentious home.

It

would be possible to consider furniture in endless detail, but my

object is rather to get at certain principles and ideals that will

form a basis for working out the minutiae, according to individual

taste. The chest is a good old-fashioned piece of furniture that may

well be revived. Any good, well-made hinged boxes, and especially

those of white cedar and the Chinese camphor-wood chests, are useful

and attractive. The Chinese chests are covered with an ugly varnish

which can be removed with strong lye, carefully rubbed on with a

stout swab. Chests covered with leather and bound in brass are very

elegant when they can be afforded. Wood-boxes near the fireplace may

be left plain, or stained, carved or burned in ornamental designs. In

a large room screens can be used to advantage. They may be made of

big simple panels of wood, or of leather, either plain or ornamented

with burning and coloring.

Chinese

teak-wood furniture is generally good in design and may be had very

richly carved. Old-fashioned mahogany bedsteads, bureaus and chairs

are often beautifully simple in their lines and appropriate to the

setting I have endeavored to picture. Oak furniture is now obtainable

made in the "old mission" style, which is so good in form

and workmanship that it leaves nothing to be desired.

The

various handicrafts are brought into play in the furnishing of the

home. Metal work is as indispensable as wood work, and again the same

general principles should govern

selection

— good work, good form, simple design. The plainest are the safest.

Locks, catches and fixtures of black iron, or of solid brass without

ornament, are sure to be unobjectionable. The andirons may also be

plain, or they may be ornamented as richly as taste suggests,

provided the work be hand-wrought.

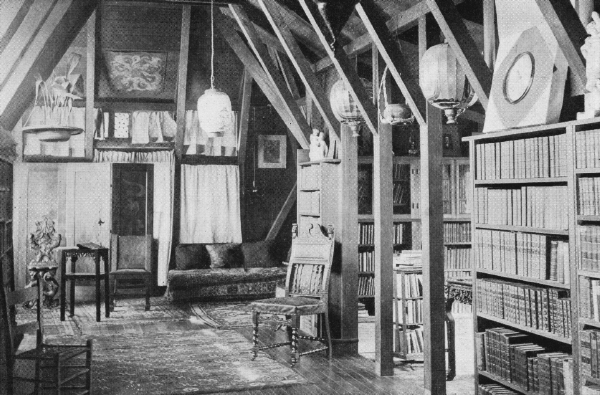

Library

of Wood with Interior Timber Work Exposed

I have

often been asked if the use of electric lights in a house which thus

emphasizes the handicrafts was not out of harmony with the spirit of

the place. Personally, I am fond of candles in brass, bronze or

silver candlesticks, but the light is neither strong nor steady

enough to satisfy the practical needs. I have found the pleasantest

results in lighting to be attained by the use of electric lights

subdued by lanterns. If the electric bulbs are suspended some six or

eight inches from the wall on brackets, they may hang as low as

desired without being in the way. Various types of Chinese, Japanese

and Moorish lanterns can be found which give a soft, pleasing light

and are very decorative. Old brass and bronze lanterns are the most

beautiful, but many simpler and less costly substitutes will be

discovered by those who search in our Oriental bazaars. Good lamps

with artistic shades are hard to find, but there is an improvement in

these to be noted which promises better things ere long. Covers for

gas and oil-stoves made of sheet brass riveted into cylinders and

ornamented according to the skill and ingenuity of the maker would be

a most acceptable addition to our furniture.

To

write of vases and

other pottery would call for one or more separate chapters, but a

hint or two may not be out of place. At the risk of repetition I

would say again that unless the ornament be unquestionably fine, do

with none at all. Chinese ginger jars, earthenware pots, Italian wine

flasks with straw casings, are all better than showy vases that are

not good in color, form or workmanship. The Japanese and Chinese are

the master potters, and if the detestable stuff which they

manufacture for the American trade be eliminated, their work is

generally good and often exquisitely beautiful. Much excellent

pottery is now made in our own country, and the number of genuinely

refined and simple wares is constantly increasing, showing a gradual

elevation of taste among our people.

Of

other useful ornaments

may be mentioned bellows, South Sea Island fans, baskets, especially

those of our own misused Indians, and hanging Japanese baskets for

plants. Potted plants add a touch of life and color which cannot be

otherwise given to a room. Masses of books have an ornamental value

which is heightened by the idea of culture of which they are the

embodiment.

It

remains now to consider only the purely non-utilitarian ornament —

statues, pictures and wall decorations. Since most dwellers in simple

homes cannot afford great works of art, they must enjoy these in

museums, and for their homes content themselves with reproductions.

Plaster casts toned to a soft creamy shade and surfaced with wax are,

if well chosen, a most effective form of ornament.

The

pictures a man selects to hang upon his wall are a perpetual witness

of his degree of culture. They are ever present as an unconscious

factor in shaping our lives and thought. They serve no useful purpose

and have no meaning except as they bring before us something of the

ideal. The test of a good picture is its inexhaustible quality, both

of form and of content; but time alone can make this test. When the

work of a master has been handed down through centuries, when it has

been copied and scrutinized and criticized by generations and still

holds its place, we may be sure that it contains something that will

enrich our lives. If the world has lived with it for ages, it needs

must profit us to dwell in its sight. We cannot have the original

picture, but a photograph giving all but its color may be obtained

for a mere trifle. Thus our walls may be graced with the thought of

Botticelli, Leonardo, Raphael and Michael Angelo, just as readily as

with the commonplace work that so often passes current for genuine

art. When we have lived with the masters for years, and have absorbed

their message, then we may trust ourselves to test the work of the

moderns in the ,light of the insight we have gained from their

predecessors. It may be urged that we want color on our walls, and

that tinted casts and photographs of the masterpieces fail to give

this. In vain I point to the Oriental rugs, the colored curtains, the

green of the potted plants — still the demand for colored pictures

must be satisfied, and this without great cost. If one really loves

form and color for themselves, I know of but one means of satisfying

this adequately and inexpensively. Japanese prints are seldom great

in idea, and they therefore miss the highest quality of art

expression, but for delicacy and subtlety of coloring and grace of

form they are unexcelled. A few prints selected with discrimination

and simply framed will give just the touch of accidental color which

the room seems to require.

California

has harbored a

number of painters of exceptional ability, and those who can afford

original paintings by our best local artists need not go abroad for

their pictures. America has produced but one Keith, and his work has

been done in San Francisco.

Many of

our artists are

now looking toward decorative work as a field of activity, instead of

confining their attention to easel pictures, and this is a most

wholesome change. A decorative frieze or a set piece designed to

occupy a given space in a room, and conceived in harmony with its

setting, is apt to be far more effective than a number of small

detached pictures scattered at random about the walls.

A word

on framing

pictures and our cursory survey of house furnishing must come to an

end. The old-fashioned idea seemed to be that a picture was merely an

excuse for displaying an elaborate frame. Now people have come to

realize that the frame is nothing but the border of the picture. Here

again a simple form is always safe. A plain, finely finished surface

without ornamentation is never out of place. In choosing the color of

a frame, the middle tone of the picture is the best guide. Thus in

framing a brown photograph, a brown mat intermediate in tone between

the high lights and the deepest shadows will probably be found most

effective. The wood is least obtrusive if toned to match the mat or

just a shade darker. Photographs look well framed in wood without a

mat, but with a fine line of gold next the picture. Gold frames are

scarcely in keeping with a simple home, but if used should be of the

finest workmanship and the most chaste design. They are, as a rule,

inappropriate except on oil paintings, although a gold mat with

simple gold border occasionally looks well on a water-color.

I know

it is not safe to

lay down the law where matters of taste are involved, but my excuse

must be that it is better to convey a definite impression, even

though it be a narrow one, rather than to be so broad that all

concreteness vanishes in glittering generalities. Many types of homes

may be good and beautiful which do not come within the compass of

this sketch. I have tried only to give some tangible expression of my

own conception of the simple home, trusting that the practical hints

embodied may be the means of showing some people who have felt the

need of more artistic surroundings a tolerably secure means of

attaining them.

|