| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER

IV. SAKKÂRAH

AND MEMPHIS. HAVING

arrived at Bedreshayn after dark, and there moored for the night, we

were

roused early next morning by the furious squabbling and chattering of

some

fifty or sixty men and boys who, with a score or two of little

rough-coated,

depressed-looking donkeys, were assembled on the high bank above. Seen

thus

against the sky, their tattered garments fluttering in the wind, their

brown

arms and legs in frantic movement, they looked like a troop of mad

monkeys let

loose. Every moment the uproar grew shriller. Every moment more men,

more boys,

more donkeys, appeared upon the scene. It was as if some new Cadmus had

been

sowing boys and donkeys broadcast, and they had all come up at once for

our

benefit. Then it

appeared that Talhamy, knowing how eight donkeys would be wanted for

our united

forces, had sent up to the village for twenty-five, intending, with

perhaps

more wisdom than justice, to select the best and dismiss the others.

The result

was overwhelming. Misled by the magnitude of the order and concluding

that

Cook’s party had arrived, every man, boy, and donkey in

Bedreshayn and the

neighbouring village of Mîtrahîneh had turned out in hot

haste and rushed down

to the river; so that by the time breakfast was over there were steeds

enough

in readiness for all the English in Cairo. I pass over the tumult that

ensued

when our party at last mounted the eight likeliest beasts and rode

away,

leaving the indignant multitude to disperse at leisure. And now

our way lies over a dusty flat, across the railway line, past the long

straggling village, and through the famous plantations known as the

Palms of

Memphis. There is a crowd of patient-looking fellaheen at the little

whitewashed station, waiting for the train, and the usual rabble of

clamorous

water, bread, and fruit-sellers. Bedreshayn, though a collection of

mere mud

hovels, looks pretty, nestling in the midst of stately date-palms.

Square

pigeon-towers, embedded round the top with layers of wide-mouthed pots

and

stuck with rows of leafless acacia-boughs like ragged banner-poles,

stand up at

intervals among the huts. The pigeons go in and out of the pots, or sit

preening their feathers on the branches. The dogs dash out and bark

madly at

us, as we go by. The little brown children pursue us with cries of

“Bakhshîsh!”

The potter, laying out rows of soft, grey, freshly-moulded clay bowls

and

kullehs1 to bake in the sun, stops open-mouthed, and stares

as if he

had never seen a European till this moment. His young wife snatches up

her baby

and pulls her veil more closely over her face, fearing the evil eye. The

village being left behind, we ride on through one long palm grove after

another; now skirting the borders of a large sheet of tranquil

back-water; now

catching a glimpse of the far-off pyramids of Ghîzeh, now passing

between the

huge irregular mounds of crumbled clay which mark the site of Memphis.

Next

beyond these we come out upon a high embanked road some twenty feet

above the

plain, which here spreads out like a wide lake and spends its last

dark-brown

alluvial wave against the yellow rocks which define the edge of the

desert.

High on this barren plateau, seen for the first time in one unbroken

panoramic

line, there stands a solemn company of pyramids; those of

Sakkârah straight

before us, those of Dahshûr to the left, those of Abusîr to

the right, and the

great pyramids of Ghîzeh always in the remotest distance. It might

be thought there would be some monotony in such a scene, and but little

beauty.

On the contrary, however, there is beauty of a most subtle and

exquisite kind –

transcendent beauty of colour, and atmosphere, and sentiment; and no

monotony

either in the landscape or in the forms of the pyramids. One of these

which we

are now approaching is built in a succession of platforms gradually

decreasing

towards the top. Another down yonder at Dahshûr curves outward at

the angles,

half dome, half pyramid, like the roof of the Palais de Justice in

Paris. No

two are of precisely the same size, or built at precisely the same

angle; and

each cluster differs somehow in the grouping. Then again

the colouring! – colouring not to be matched with any pigments

yet invented.

The Libyan rocks, like rusty gold – the paler hue of the driven

sand-slopes –

the warm maize of the nearer pyramids which, seen from this distance,

takes a

tender tint of rose, like the red bloom on an apricot – the

delicate tone of

these objects against the sky – the infinite gradation of that

sky, soft and

pearly towards the horizon, blue and burning towards the zenith –

the

opalescent shadows, pale blue, and violet, and greenish-grey, that

nestle in

the hollows of the rock and the curves of the sand-drifts – all

this is beautiful

in a way impossible to describe, and alas! impossible to copy. Nor does

the

lake-like plain with its palm-groves and corn-flats form too tame a

foreground.

It is exactly what is wanted to relieve that glowing distance. And now,

as we follow the zig-zag of the road, the new pyramids grow gradually

larger;

the sun mounts higher; the heat increases. We meet a train of camels,

buffaloes, shabby grown sheep, men, women, and children of all ages.

The camels

are laden with bedding, rugs, mats, and crates of poultry, and carry,

besides,

two women with babies and one very old man. The younger men drive the

tired

beasts. The rest follow behind. The dust rises after them in a cloud.

It is

evidently the migration of a family of three, if not four generations.

One

cannot help being struck by the patriarchal simplicity of the incident.

Just

thus, with flocks and herds and all his clan, went Abraham into the

land of

Canaan close upon four thousand years ago; and one at least of these

Sakkârah

pyramids was even then the oldest building in the world. It

is a

touching and picturesque procession – much more picturesque than

ours, and much

more numerous; notwithstanding that our united forces, including

donkey-boys,

porters, and miscellaneous hangers-on, number nearer thirty than twenty

persons. For there are the M. B.s and their nephew, and L.----- and the

writer, and L.-----’s maid, and Talhamy, all on donkeys; and then

there are the

owners of the

donkeys, also on donkeys; and then every donkey has a boy; and every

boy has a donkey;

and every donkey-boy’s donkey has an inferior boy in attendance.

Our style of

dress, too, however convenient, is not exactly in harmony with the

surrounding

scenery; and one cannot but feel, as these draped and dusty pilgrims

pass us on

the road, that we cut a sorry figure with our hideous palm-leaf hats,

green

veils, and white umbrellas. But the

most amazing and incongruous personage in our whole procession is

unquestionably George. Now George is an English north-country groom

whom the M.

B.s have brought out from the wilds of Lancashire, partly because he is

a good

shot and may be useful to “Master Alfred” after birds and

crocodiles; and

partly from a well-founded belief in his general abilities. And George,

who is

a fellow of infinite jest and infinite resource, takes to Eastern life

as a

duckling to the water. He picks up Arabic as if it were his mother

tongue. He

skins birds like a practised taxidermist. He can even wash and iron on

occasion. He is, in short, groom, footman, housemaid, laundry-maid,

stroke oar,

game-keeper, and general factotum all in one. And besides all this, he

is

gifted with a comic gravity of countenance that no surprises and no

disasters

can upset for a moment. To see this worthy anachronism cantering along

in his

groom’s coat and gaiters, livery-buttons, spotted neckcloth, tall

hat, and all

the rest of it; his long legs dangling within an inch of the ground on

either

side of the most diminuitive of donkeys; his double-barrelled

fowling-piece

under his arm, and that imperturbable look in his face, one would have

sworn

that he and Egypt were friends of old, and that he had been brought up

on

pyramids from his earliest childhood. It is a

long and shelterless ride from the palms to the desert; but we come to

the end

of it at last, mounting just such another sand-slope as that which

leads up

from the Ghîzeh road to the foot of the great pyramid. The edge

of the plateau

here rises abruptly from the plain in one long range of low

perpendicular

cliffs pierced with dark mouths of rock-cut sepulchres, while the

sand-slope by

which we are climbing pours down through a breach in the rock, as an

Alpine

snow-drift flows through a mountain gap from the ice-level above. And now,

having dismounted through compassion for our unfortunate little

donkeys, the

first thing we observe is the curious mixture of débris

underfoot. At Ghîzeh

one treads only sand and pebbles; but here at Sakkârah the whole

plateau is

thickly strewn with scraps of broken pottery, limestone, marble, and

alabaster;

flakes of green and blue glaze; bleached bones; shreds of yellow linen;

and

lumps of some odd-looking dark brown substance, like dried-up sponge.

Presently

some one picks up a little noseless head of one of the common

blue-water

funereal statuettes, and immediately we all fall to work, grubbing for

treasure

– a pure waste of precious time; for though the sand is full of

débris, it has

been sifted so often and so carefully by the Arabs that it no longer

contains

anything worth looking for. Meanwhile, one finds a fragment of

iridescent glass

– another, a morsel of shattered vase – a third, an opaque

bead of some kind of

yellow paste. And then, with a shock which the present writer, at all

events,

will not soon forget, we suddenly discover that these scattered bones

are human

– that those linen shreds are shreds of cerement cloths –

that yonder

odd-looking brown lumps are rent fragments of what once was living

flesh! And

now for the first time we realize that every inch of this ground on

which we

are standing, and all these hillocks and hollows and pits in the sand,

are

violated graves. “Ce n’est

que le premier pas que coûte.” We soon became quite

hardened to such sights,

and learned to rummage among dusty sepulchres with no more compunction

than

would have befitted a gang of professional body-snatchers. These are

experiences upon which one looks back afterwards with wonder, and

something

like remorse; but so infectious is the universal callousness, and so

overmastering is the passion for relic-hunting, that I do not doubt we

should

again do the same things under the same circumstances. Most Egyptian

travellers, if questioned, would have to make a similar confession.

Shocked at

first, they denounce with horror the whole system of sepulchral

excavation,

legal as well as predatory; acquiring, however, a taste for scarabs and

funerary statuettes, they soon begin to buy with eagerness the spoils

of the

dead; finally they forget all their former scruples, and ask no better

fortune

than to discover and confiscate a tomb for themselves. Notwithstanding

that I had first seen the pyramids of Ghîzeh, the size of the

Sakkârah group –

especially of the pyramid in platforms – took me by surprise.

They are all

smaller than the pyramids of Khufu and Khafra, and would no doubt look

sufficiently

insignificant if seen with them in close juxtaposition; but taken by

themselves

they are quite vast enough for grandeur. As for the pyramid in

platforms (which

is the largest at Sakkârah, and next largest to the pyramid of

Khafra) its

position is so fine, its architectural style so exceptional, its age so

immense, that one altogether loses sight of these questions of relative

magnitude. If Egyptologists are right in ascribing the royal title

hieroglyphed

on the inner door of this pyramid to Ouenephes, the fourth king of the

First

Dynasty, then it is the most ancient building in the world. It had been

standing from five to seven hundred years when King Khufu began his

great pyramid at Ghîzeh. It was over two thousand years old when

Abraham was born. It

is now about six thousand eight hundred years old according to Manetho

and

Mariette, or about four thousand eight hundred according to the

computation of

Bunsen. One’s imagination recoils upon the brink of such a gulf

of time. The door

of this pyramid was carried off, with other precious spoils, by

Lepsius, and is

now in the museum at Berlin. The evidence that identifies the

inscription is

tolerably direct. According to Manetho, an Egyptian historian who wrote

in

Greek and lived in the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphus, King Ouenephes

built for

himself a pyramid at a place called Kokhome. Now a tablet discovered in

the

Serapeum by Mariette gives the name of Ka-kem to the necropolis of

Sakkârah;

and as the pyramid in stages is not only the largest on this platform,

but is

also the only one in which a royal cartouche has been found, the

conclusion

seems obvious. When a

building has already stood five or six thousand years in a climate

where mosses

and lichens, and all those natural signs of age to which we are

accustomed in

Europe are unknown, it is not to be supposed that a few centuries more

or less

can tell upon its outward appearance; yet to my thinking the pyramid of

Ouenephes looks older than those of Ghîzeh. If this be only

fancy, it gives

one, at all events, the impression of belonging structurally to a ruder

architectural period. The idea of a monument composed of diminishing

platforms

is in its nature more primitive than that of a smooth four-sided

pyramid. We

remarked that the masonry on one side – I think on the side

facing eastwards –

was in a much more perfect condition than on either of the others. Wilkinson

describes the interior as “a hollow dome supported here and there

by wooden

rafters,” and states that the sepulchral chamber was lined with

blue porcelain

tiles.2 We would have liked to go inside, but this is no

longer

possible, the entrance being blocked by a recent fall of masonry. Making up

now for lost time, we rode on as far as the house built in 1850 for

Mariette’s

accomodation during the excavation of the Serapeum – a labour

which extended

over a period of more than four years. The

Serapeum, it need hardly be said, is the famous and long-lost

sepulchral temple

of the sacred bulls. These bulls (honoured by the Egyptians as

successive

incarnations of Osiris) inhabited the temple of Apis at Memphis while

they

lived; and being mummied after death, were buried in catacombs prepared

for

them in the desert. In 1850, Mariette, travelling in the interests of

the

French Government, discovered both the temple and the catacombs, being,

according to his own narrative, indebted for the clue to a certain

passage in

Strabo, which describes the Temple of Serapis as being situate in a

district

where the sand was so drifted by the wind that the approach to it was

in danger

of being overwhelmed; while the sphinxes on either side of the great

avenue

were already more or less buried, some having only their heads above

the

surface. “If Strabo had not written this passage,” says

Mariette, “it is

probable that the Serapeum would still be lost under the sands of the

necropolis of Sakkârah. One day, however (in 1850), being

attracted to Sakkârah

by my Egyptological studies, I perceived the head of a sphinx showing

above the

surface. It evidently occupied its original position. Close by lay a

libation-table on which was engraved a hieroglyphic inscription to

Apis-Osiris.

Then that passage in Strabo came to my memory, and I knew that beneath

my feet

lay the avenue leading to the long and vainly sought Serapeum. Without

saying a

word to any one, I got some workmen together and we began excavating.

The

beginning was difficult; but soon the lions, the peacocks, the Greek

statues of

the Dromos, the inscribed tablets of the Temple of Nectanebo3 rose

up from the sands. Thus was the Serapeum discovered.” The house

– a slight, one-story building on a space of rocky platform

– looks down upon a

sandy hollow which now presents much the same appearance that it must

have

presented when Mariette was first reminded of the fortunate passage in

Strabo.

One or two heads of sphinxes peep up here and there in a ghastly way

above the

sand, and mark the line of the great avenue. The upper half of a boy

riding on

a peacock, apparently of rude execution, is also visible. The rest is

already

as completely overwhelmed as if it had never been uncovered. One can

scarcely

believe that only twenty years ago, the whole place was entirely

cleared at so

vast an expenditure of time and labour. The work, as I have already

mentioned,

took four years to complete. This avenue alone was six hundred feet in

length

and bordered by an army of sphinxes, one hundred and forty-one of which

were

found in situ. As the excavation neared the end of the avenue,

the

causeway, which followed a gradual descent between massive walls, lay

seventy

feet below the surface. The labour was immense, and the difficulties

were

innumerable. The ground had to be contested inch by inch. “In

certain places,”

says Mariette, “the sand was fluid, so to speak, and baffled us

like water

continually driven back and seeking to regain its level.”4 If,

however, the toil was great, so also was the reward. A main avenue

terminated

by a semicircular platform, around which stood statues of famous Greek

philosophers and poets; a second avenue at right angles to the first;

the

remains of the great temple of the Serapeum; three smaller temples; and

three

distinct groups of Apis catacombs, were brought to light. A descending

passage

opening from a chamber in the great Temple led to the catacombs –

vast labyrinths

of vaults and passages hewn out of the solid rock on which the Temples

were

built. These three groups of excavations represent three epochs of

Egyptian

history. The first and most ancient series consists of isolated vaults

dating

from the eighteenth to the twenty-second dynasty; that is to say, from about B.C.

1703 to

B.C. 980. The second group, which dates from the reign of Sheshonk I

(twenty-second

dynasty, B.C. 980) to that of Tirhakah, the last king of the twenty-fifth

dynasty, is

more systematically planned, and consists of one long tunnel bordered

on each

side by a row of funereal chambers. The third belongs to the Greek

period,

beginning with Psammetichus I (twenty-sixth dynasty, B.C. 665) and ending

with the

latest Ptolemies. Of these, the first are again choked with sand; the

second

are considered unsafe; and the third only is accessible to travellers. After a

short but toilsome walk, and some delay outside a prison-like door at

the

bottom of a steep descent, we were admitted by the guardian – a

gaunt old Arab

with a lantern in his hand. It was not an inviting looking place

within. The

outer daylight fell upon a rough step or two, beyond which all was

dark. We

went in. A hot, heavy atmosphere met us on the threshold; the door fell

to with

a dull clang, the echoes of which went wandering away as if into the

central

recesses of the earth; the Arab chattered and gesticulated. He was

telling us

that we were now in the great vestibule, and that it measured ever so

many feet

in this and that direction; but we could see nothing – neither

the vaulted roof

overhead, nor the walls on any side, nor even the ground beneath our

feet. It

was like the darkness of infinite space. A lighted

candle was then given to each person, and the Arab led the way. He went

dreadfully fast, and it seemed at every step as if one were on the

brink of

some frightful chasm. Gradually, however, our eyes became accustomed to

the

gloom, and we found that we had passed out of the vestibule into the

first

great corridor. All was vague, mysterious, shadowy. A dim perspective

loomed

out of the darkness. The lights twinkled and flitted, like wandering

sparks of

stars. The Arab held his lantern to the walls here and there, and

showed us

some votive tablets inscribed with records of pious visits paid by

devout

Egyptians to the sacred tombs. Of these they found five hundred when

the

catacombs were first opened; but Mariette sent nearly all to the

Louvre. A few

steps farther, and we came to the tombs – a succession of great

vaulted

chambers hewn out at irregular distances along both sides of the

central

corridor, and sunk some six or eight feet below the surface. In the

middle of

each chamber stood an enormous sarcophagus of polished granite. The

Arab,

flitting on ahead like a black ghost, paused a moment before each

cavernous

opening, flashed the light of his lantern on the sarcophagus, and sped

away

again, leaving us to follow as we could. So we went

on, going every moment deeper into the solid rock, and farther from the

open

air and the sunshine. Thinking it would be cold underground, we had

brought

warm wraps in plenty; but the heat, on the contrary, was intense, and

the

atmosphere stifling. We had not calculated on the dryness of the place,

nor had

we remembered that ordinary mines and tunnels are cold because they are

damp.

But here for incalculable ages – for thousands of years probably

before the

Nile had even cut its path through the rocks of Silsilis – a

cloudless African

sun had been pouring its daily floods of light and heat upon the

dewless desert

overhead. The place might well be unendurable. It was like a great oven

stored

with the slowly accumulated heat of cycles so remote, and so many, that

the

earliest periods of Egyptian history seem, when compared with them, to

belong

to yesterday. Having

gone on thus for a distance of nearly two hundred yards, we came to a

chamber

containing the first hieroglyphed sarcophagus we had yet seen; all the

rest

being polished, but plain. Here the Arab paused; and finding access

provided by

means of a flight of wooden steps, we peeped inside by the help of a

ladder,

and examined the hieroglyphs with which it is covered. Enormous as they

look

from above, one can form no idea of the bulk of these huge monolithic

masses

except from the level on which they stand. This sarcophagus, which

dates from

the reign of Amasis, of the twenty-sixth dynasty, measured fourteen feet in

length by

eleven in height, and consisted of a single block of highly-wrought

black

granite. Four persons might sit in it round a small card-table, and

play a

rubber comfortably. From this

point the corridor branches off for another two hundred yards or so,

leading

always to more chambers and more sarcophagi, of which last there are

altogether

twenty-four. Three only are inscribed; none measure less than from

thirteen to

fourteen feet in length; and all are empty. The lids in every instance

have

been pushed back a little way, and some are fractured; but the spoilers

have

been unable wholly to remove them. According to Mariette, the place was

pillaged by the early Christians, who, besides carrying off whatever

they could

find in the way of gold and jewels, seem to have destroyed the mummies

of the

bulls, and razed the great temple nearly to the ground. Fortunately,

however,

they either overlooked, or left as worthless, some hundreds of

exquisite

bronzes and the five hundred votive tables before mentioned, which, as

they

record not only the name and rank of the visitor, but also, with few

exceptions, the name and year of the reigning Pharaoh, afford

invaluable

historical data, and are likely to do more than any previously

discovered

documents towards clearing up disputed points of Egyptian chronology. It is a

curious fact that one out of the three inscribed sarcophagi should bear

the

oval of Cambyses – that Cambyses of whom it is related that,

having desired the

priests of Memphis to bring before him the god Apis, he drew his dagger

in a

transport of rage and contempt, and stabbed the animal in the thigh.

According

to Plutarch, he slew the beast and cast out its body to the dogs;

according to

Herodotus, “Apis lay some time pining in the temple, but at last

died of his

wound, and the priests buried him secretly;” but according to one

of these

previous Serapeum tablets the wounded bull did not die till the fourth

year of

the reign of Darius. So wonderfully does modern discovery correct and

illustrate tradition. And now

comes the sequel to this ancient story in the shape of an anecdote

related by

M. About, who tells how Mariette, being recalled suddenly to Paris some

months

after the opening of the Serapeum, found himself without the means of

carrying

away all his newly excavated antiquities, and so buried fourteen cases

in the

desert, there to await his return. One of these cases contained an Apis

mummy

which had escaped discovery by the early Christians; and this mummy was

that of

the identical Apis stabbed by Cambyses. That the creature had actually

survived

his wound was proved by the condition of one of the thigh-bones, which

showed

unmistakable signs of both injury and healing. Nor does

the story end here. Mariette being gone, and having taken with him all

that was

most portable among his treasures, there came to Memphis one whom M.

About

indicates as “a young and august stranger” travelling in

Egypt for his

pleasure. The Arabs, tempted perhaps by a princely bakhshish, revealed

the

secret of the hidden cases; whereupon the Archduke swept off the whole

fourteen, despatched them to Alexandria, and immediately shipped them

for

Trieste.5 “Quant au coupable,” says M. About who professes

to have had the

story direct from Mariette, “il a fini si tragiquement dans un

autre hemisphère

que, tout bien pesé, je renonce à publier son nom.”

But through so transparent

a disguise it is not difficult to identify the unfortunate hero of this

curious

anecdote. The

sarcophagus in which the Apis was found remains in the vaults of the

Serapeum;

but we did not see it. Having come more than two hundred yards already,

and

being by this time well-nigh suffocated, we did not care to put two

hundred

yards more between ourselves and the light of day. So we turned back at

the

half distance – having, however, first burned a pan of magnesian

powder, which

flared up wildly for a few seconds; lit the huge gallery and all its

cavernous

recesses and the wondering faces of the Arabs; and then went out with a

plunge,

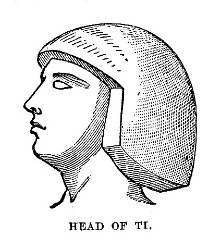

leaving the darkness denser than before. From

hence, across a farther space of sand, we went in all the blaze of noon

to the

tomb of one Ti, a priest and commoner of the Fifth Dynasty, who married

with a

lady named Nefer-hotep-s, the granddaughter of a Pharaoh, and here

built

himself a magnificent tomb in the desert. Of the

façade of this tomb, which must originally have looked like a

little temple,

only two large pillars remain. Next comes a square courtyard surrounded

by a

roofless colonnade, from one corner of which a covered passage leads to

two

chambers. In the centre of the courtyard yawns an open pit some

twenty-five

feet in depth, with a shattered sarcophagus just visible in the gloom

of the

vault below. All here is limestone – walls, pillars, pavements,

even the

excavated débris with which the pit had been filled in when the

vault was

closed for ever. The quality of this limestone is close and fine like

marble,

and so white that, although the walls and columns of the courtyard are

covered

with sculptures of most exquisite execution and of the greatest

interest, the

reflected light is so intolerable, that we find it impossible to

examine them

with the interest they deserve. In the passage, however, where there is

shade,

and in the large chamber, where it is so dark that we can see only by

the help

of lighted candles, we find a succession of bas-reliefs so numerous and

so

closely packed that it would take half a day to see them properly.

Ranged in

horizontal parallel lines about a foot and a half in depth, these

extraordinary

pictures, row above row, cover every inch of wall-space from floor to

ceiling.

The relief is singularly low. I should doubt if it anywhere exceeds a

quarter

of an inch. The surface, which is covered with a thin film of very fine

cement,

has a quality and polish like ivory. The figures measure an average

height of

about twelve inches, and all are coloured. Here, as

in an open book, we have the biography of Ti. His whole life, his

pleasures,

his business, his domestic relations, are brought before us with just

that

faithful simplicity which makes the charm of Montaigne and Pepys. A

child might

read the pictured chronicles which illuminate these walls, and take as

keen a

pleasure in them as the wisest of archæologists. Ti was a

wealthy man, and his wealth was of the agricultural sort. He owned

flocks and

herds and vassals in plenty. He kept many kinds of birds and beasts

– geese,

ducks, pigeons, cranes, oxen, goats, asses, antelopes, and gazelles. He

was

fond of fishing and fowling, and used sometimes to go after crocodiles

and

hippopotamuses, which came down as low as Memphis in his time. He was a

kind

husband too, and a good father, and loved to share his pleasures with

his

family. Here we see him sitting in state with his wife and children,

while

professional singers and dancers perform before them. Yonder they walk

out

together and look on while the farm-servants are at work, and watch the

coming

in of the boats that bring home the produce of Ti’s more distant

lands. Here

the geese are being driven home; the cows are crossing a ford; the oxen

are

ploughing; the sower is scattering his seed; the reaper plies his

sickle; the

oxen tread the grain; the corn is stored in the granary. There are

evidently no

independent tradesfolk in these early days of the world. Ti has his own

artificers on his own estate, and all his goods and chattels are

home-made.

Here the carpenters are fashioning new furniture for the house; the

shipwrights

are busy on new boats; the potters mould pots; the metal-workers smelt

ingots

of red gold. It is plain to see that Ti lived like a king within his

own

boundaries. He makes an imposing figure, too, in all these scenes, and,

being

represented about eight times as large as his servants, sits and stands

a giant

among pigmies. His wife (we must not forget that she was of the blood

royal) is

as big as himself; and the children are depicted about half the size of

their

parents. Curiously enough, Egyptian art never outgrew this early

naïveté. The

great man remained a big man to the last days of the Ptolemies, and the

fellah

was always a dwarf.6 Apart from these and one or two other mannerisms, nothing can be more natural than the drawing, or more spirited than the action, of all these men and animals. The most difficult and transitory movements are expressed with masterly certitude. The donkey kicks up his heels and brays – the crocodile plunges – the wild duck rises on the wing; and the fleeting action is caught in each instance with a truthfulness that no Landseer could distance. The forms, which have none of the conventional stiffness of later Egyptian work, are modelled roundly and boldly, yet finished with exquisite precision and delicacy. The colouring, however, is purely decorative; and being laid on in single tints, with no attempt at gradation or shading, conceals rather than enhances the beauty of the sculptures. These, indeed, are best seen where the colour is entirely rubbed off. The tints are yet quite brilliant in parts of the larger chamber; but in the passage and courtyard, which have been excavated only a few years and are with difficulty kept clear from day to day, there is not a vestige of colour left. This is the work of the sand – that patient labourer whose office it is not only to preserve but to destroy. The sand secretes and preserves the work of the sculptor, but it effaces the work of the painter. In sheltered places where it accumulates passively like a snow-drift, it brings away only the surface-detail, leaving the under colours rubbed and dim. But nothing, as I had occasion constantly to remark in the course of the journey, removes colour so effectually as sand which is exposed to the shifting action of the wind.

How pleasant

it was, after being suffocated in the Serapeum and broiled in the tomb

of Ti,

to return to Mariette’s deserted house, and eat our luncheon on

the cool stone

terrace that looks northward over the desert! Some wooden tables and

benches

are hospitably left here for the accomodation of travellers, and fresh

water in

ice-cold kullehs is provided by the old Arab guardian. The yards and

offices at

the back are full of broken statues and fragments of inscriptions in

red and

black granite. Two sphinxes from the famous avenue adorn the terrace,

and look

down upon their half-buried companions in the sand-hollow below. The

yellow

desert, barren and undulating, with a line of purple peaks on the

horizon,

reaches away into the far distance. To the right, under a jutting ridge

of

rocky plateau not two hundred yards from the house, yawns an

open-mouthed

black-looking cavern shored up with heavy beams and approached by a

slope of

débris. This is the forced entrance to the earlier vaults of the

Serapeum, in

one of which was found a mummy described by Mariette as that of an

Apis, but

pronounced by Brugsch to be the body of Prince Kha-em-uas, governor of

Memphis

and the favourite son of Rameses the Great. This

remarkable mummy, which looked as much like a bull as a man, was found

covered

with jewels and gold chains and precious amulets engraved with the name

of

Kha-em-uas, and had on its face a golden mask; all which treasures are

now to

be seen in the Louvre. If it was the mummy of an Apis, then the jewels

with

which it was adorned were probably the offering of the prince at that

time

ruling in Memphis. If, on the contrary, it was the mummy of a man,

then, in

order to be buried in a place of peculiar sanctity, he probably usurped

one of

the vaults prepared for the god. The question is a curious one, and

remains

unsolved to this day; but it could no doubt be settled at a glance by

Professor

Owen.8 Far more

startling, however, than the discovery of either Apis or jewels, was a

sight

beheld by Mariette on first entering that long-closed sepulchral

chamber. The

mine being sprung and the opening cleared, he went in alone; and there,

on the

thin layer of sand that covered the floor, he found the footprints of

the

workmen who, 3700 years9 before, had laid this shapeless

mummy in its

tomb and closed the doors upon it, as they believed, for ever. And now –

for this afternoon is already waning fast – the donkeys are

brought round, and

we are told that it is time to move on. We have the site of Memphis and

the

famous prostrate colossus yet to see, and the long road lies all before

us. So

back we ride across the desolate sands; and with a last, long, wistful

glance

at the pyramid in platforms, go down the territory of the dead into the

land of

the living. There is a

wonderful fascination about this pyramid. One is never weary of looking

at it –

of repeating to one’s self that it is indeed the oldest building

on the face of

the whole earth. The king who erected it came to the throne, according

to

Manetho, about eighty years after the death of Mena, the founder of the

Egyptian monarchy. All we have of him is his pyramid; all we know of

him is his

name. And these belong, as it were, to the infancy of the human race.

In

dealing with Egyptian dates, one is apt to think lightly of periods

that count

only by centuries; but it is a habit of mind which leads to error, and

it

should be combated. The present writer found it useful to be constantly

comparing relative chronological eras; as, for instance, in realizing

the

immense antiquity of the Sakkârah pyramid, it is some help to

remember that

from the time when it was built by King Ouenephes to the time when King

Khufu

erected the great pyramid of Ghîzeh, there probably lies a space

of years

equivalent to that which, in the history of England, extends from the

date of

the Conquest to the accession of George the Second.10 And

yet Khufu

himself – the Cheops of the Greek historians – is but a

shadowy figure hovering

upon the threshold of Egyptian history. And now

the desert is left behind, and we are nearing the palms that lead to

Memphis.

We have of course been dipping into Herodotus – every one takes

Herodotus up

the Nile – and our heads are full of the ancient glories of this

famous city.

We know that Mena turned the course of the river in order to build it

on the

very spot, and that all the most illustrious Pharaohs adorned it with

temples,

palaces, pylons, and precious sculptures. We had read of the great

Temple of

Ptah that Rameses the Great enriched with colossi of himself; and of

the

sanctuary where Apis lived in state, taking his exercise in a pillared

courtyard where every column was a statue; and of the artificial lake,

and the

sacred groves, and the obelisks, and all the wonders of a city which

even in

its later days was one of the most populous in Egypt. Thinking

over these things by the way, we agree that it is well to have left

Memphis

till the last. We shall appreciate it the better for having first seen

that

other city on the edge of the desert to which, for nearly six thousand

years,

all Memphis was quietly migrating, generation after generation. We know

now how

poor folk laboured, and how great gentlemen amused themselves, in those

early

days when there were hundreds of country gentlemen like Ti, with

townhouses at

Memphis and villas by the Nile. From the Serapeum, too, buried and

ruined as it

is, one cannot but come away with a profound impression of the

splendour and

power of a religion which could command for its myths such faith, such

homage,

and such public works. And now we

are once more in the midst of the palm-woods, threading our way among

the same

mounds that we passed in the morning. Presently those in front strike

away from

the beaten road across a grassy flat to the right; and the next moment

we are

all gathered round the brink of a muddy pool in the midst of which lies

a

shapeless block of blackened and corroded limestone. This, it seems, is

the

famous prostrate colossus of Rameses the Great, which belongs to the

British

nation, but which the British Government is too economical to remove.11

So

here it lies, face downward; drowned once a year by the Nile; visible

only when

the pools left by the inundation have evaporated, and all the muddy

hollows are

dried up. It is one of two which stood at the entrance to the great temple of

Ptah; and by those who have gone down into the hollow and seen it from

below in

the dry season, it is reported of as a noble and very beautiful

specimen of one

of the best periods of Egyptian art. Where,

however, is the companion colossus? Where is the temple itself? Where

are the

pylons, the obelisks, the avenues of sphinxes? Where, in short, is

Memphis? The

dragoman shrugs his shoulders and points to the barren mounds among the

palms. They look

like gigantic dust-heaps, and stand from thirty to forty feet above the

plain.

Nothing grows upon them, save here and there a tuft of stunted palm;

and their

substance seems to consist chiefly of crumbled brick, broken potsherds,

and

fragments of limestone. Some few traces of brick foundations and an

occasional

block or two of shaped stone are to be seen in places low down against

the foot

of one or two of the mounds; but one looks in vain for any sign which

might

indicate the outline of a boundary wall, or the position of a great

public

building. And is

this all? No – not

quite all. There are some mud-huts yonder, in among the trees; and in

front of

one of these we find a number of sculptured fragments – battered

sphinxes,

torsos without legs, sitting figures without heads – in green,

black, and red

granite. Ranged in an irregular semicircle on the sward, they seem to

sit in

forlorn conclave, half solemn, half ludicrous, with the goats browsing

round,

and the little Arab children hiding behind them. Near this,

in another pool, lies another red granite colossus – not the

fellow to that

which we saw first, but a smaller one – also face downwards. And this

is all that remains of Memphis, eldest of cities – a few huge

rubbish-heaps, a

dozen or so of broken statues, and a name! One looks round, and tries

in vain to

realise the lost splendours of the place. Where is the Memphis that

King Mena

came from Thinis to found – the Memphis of Ouenephes, and Khufu,

and Khafra,

and all the early kings who built their pyramid-tombs in the adjacent

dessert?

Where is the Memphis of Herodotus, of Strabo, of

‘Abd-el-Latîf? Where are those

stately ruins which, even in the middle ages, extended over a space

estimated

at “half a day’s journey in every direction”? One can

hardly believe that a

great city ever flourished on this spot, or understand how it should

have been

effaced so utterly. Yet here it stood – here where the grass is

green, and the

palms are growing, and the Arabs build their hovels on the verge of the

inundation. The great colossus marks the site of the main entrance to

the

Temple of Ptah. It lies where it fell, and no man has moved it. That

tranquil

sheet of palm-fringed back-water, beyond which we see the village of

Mitrâhîneh

and catch a distant glimpse of the pyramids of Ghîzeh, occupies

the basin of a

vast artificial lake excavated by Mena. The very name of Memphis

survives in

the dialect of the fellah, who calls the place of the mounds Tell Monf12

–

just as Sakkârah fossilises the name of Sokari, one of the

special

denominations of the Memphite Osiris. No capital

in the world dates so far back as this, or kept its place in history so

long.

Founded four thousand years before our era, it beheld the rise and fall

of

thirty-one dynasties; it survived the rule of the Persian, the Greek,

and the

Roman; it was, even in its decadence, second only to Alexandria in

population

and extent; and it continued to be inhabited up to the time of the Arab

invasion. It then became the quarry from which Fostât was built;

and as the new

city rose on the eastern bank, the people of Memphis quickly abandoned

their

ancient capital to desolation and decay. Still a

vast field of ruins remained. Abd-el-Latîf, writing at the

commencement of the

thirteenth century, speaks with enthusiasm of the colossal statues and

lions,

the enormous pedestals, the archways formed of only three stones, the

bas-reliefs and other wonders that were yet to be seen upon the spot.

Marco

Polo, if his wandering tastes had led him to the Nile, might have found

some of

the palaces and temples of Memphis still standing; and Sandys, who in

A.D. 1610

went at least as far south of Cairo as Kafr el Iyat, says that

“up the River

for twenty miles space there was nothing but ruines.” Since then,

however, the

very “ruines” have vanished; the palms have had time to

grow; and modern Cairo

has doubtless absorbed all the building material that remained from the

middle

ages. Memphis is

a place to read about, and think about, and remember; but it is a

disappointing

thing to see. To miss it, however, would be to miss the first link in

the whole

chain of monumental history which unites the Egypt of antiquity with

the world

of to-day. Those melancholy mounds and that heron-haunted lake must be

seen, if

only that they may take their due place in the picture-gallery of

one’s memory.

It had been

a long day’s work, but it came to an end at last; and as we

trotted our donkeys

back towards the river, a gorgeous sunset was crimsoning the palms and

pigeon-towers of Bedreshayn. Everything seemed now to be at rest. A

buffalo,

contemplatively chewing the cud, lay close against the path and looked

at us

without moving. The children and pigeons were gone to bed. The pots had

baked

in the sun and been taken in long since. A tiny column of smoke went up

here

and there from amid the clustered huts; but there was scarcely a moving

creature to be seen. Presently we passed a tall, beautiful fellah woman

standing grandly by the wayside, with her veil thrown back and falling

in long

folds to her feet. She smiled, put out her hand, and murmured

“Bakhshîsh!” Her

fingers were covered with rings, and her arms with silver braclets. She

begged

because to beg is honourable, and customary, and a matter of inveterate

habit;

but she evidently neither expected nor needed the bakhshîsh she

condescended to

ask for. A few moments more and the sunset has faded, the village is left behind, the last half-mile of plain is trotted over. And now – hungry, thirsty, dusty, worn out with new knowledge, new impressions, new ideas – we are once more at home and at rest. __________________________

1 The

goolah, or kulleh, is a porous water-jar of sun-dried Nile mud. These

jars are

made of all sizes and in a variety of remarkably graceful forms, and

cost from

about one farthing to twopence apiece. 2 Some of

these tiles are to be seen in the Egyptian department of the British

Museum.

They are not blue, but of a bluish green. For a view of the sepulchral

chamber,

see Maspero’s "Archæologie Egyptienne," Fig. 230, p.

256. [Note to the second edition.] 3 Nectanebo

I and Nectanebo II were the last native Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, and

flourished between B.C. 378 and B.C. 340. An earlier temple must have

preceded

the Serapeum built by Nectanebo I. 4 For an

excellent and exact account of the Serapeum and the monuments there

discovered,

see M. Arthur Rhoné’s "L’Egypte en Petites

Journées," of which a new

edition is now in the press. [Note to second edition.] 5 These

objects, known as “The Miramar Collection,” and catalogued

by Professor

Reinisch, are now removed to Vienna. [Note to second edition.] 6 A more

exhaustive study of the funerary texts has of late revolutionised our

interpretation of these, and similar sepulchral tableaux. The scenes

they

represent are not, as was supposed when this book was first written,

mere

episodes in the daily life of the deceased; but are links in the

elaborate

story of his burial and his ghostly existence after death. The corn is

sown,

reaped, and gathered in order that it may be ground and made into

funerary

cakes; the oxen, goats, gazelles, geese, and other live stock are

destined for

sacrificial offerings; the pots, and furniture, and household goods are

for

burying with the mummy in his tomb; and it is his “Ka,” or

ghostly double, that

takes part in these various scenes, and not the living man. [Note to second edition.] 7 These

statues were not mere portrait-statues; but were designed as bodily

habitations

for the incorporeal ghost, or “Ka,” which it was

supposed needed a body,

food, and drink, and must perish everlastingly if not duly supplied

with these

necessaries. Hence the whole system of burying food-offerings,

furniture,

stuffs, etc., in ancient Egyptian sepulchres. [Note to second edition.]

8 The actual

tomb of Prince Kha-em-uas has been found at Memphis by M. Maspero,

within the

last three or four years. [Note to second edition.] 9 The date

is Mariette’s. 10 There was

no worship of Apis in the days of King Ouenephes, nor, indeed, until

the reign

of Kaiechos, more than one hundred and twenty years after this time.

But at

some subsequent period of the Ancient Empire, his pyramid was

appropriated by

the priests of Memphis for the mummies of the Sacred Bulls. This, of

course,

was done before any of the known Apis-catacombs were excavated. There

are

doubtless many more of these catacombs yet undiscovered, nothing prior

to the

eighteenth dynasty having yet been found. 11 This

colossus is now raised upon a brick pedestal. [Note to second edition.]

12 Tell: Arabic

for mound. Many of these mounds preserve the ancient names of the

cities they

entomb; as Tell Basta (Bubastis); Kóm Ombo (Ombos); etc. etc. Tell

and Kóm

are synonymous terms. |