| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER

VII. SIÛT TO

DENDERAH. WE started

from Siût with a couple of tons of new brown bread on board,

which, being cut

into slices and laid to dry in the sun, was speedily converted into

rusks and

stored away in two huge lockers on the upper deck. The sparrows and

water-wagtails had a good time while the drying went on; but no one

seemed to

grudge the toll they levied. We often

had a “big wind” now; though it seldom began to blow before

ten or eleven A.M.,

and generally fell at sunset. Now and then, when it chanced to keep up,

and the

river was known to be free from shallows, we went on sailing through

the night;

but this seldom happened, and when it did happen, it made sleep

impossible – so

that nothing but the certainty of doing a great many miles between

bed-time and

breakfast could induce us to put up with it. We had now

been long enough afloat to find out that we had almost always one man

on the

sick list, and were therefore habitually short of a hand for the

navigation of

the boat. There never were such fellows for knocking themselves to

pieces as

our sailors. They were always bruising their feet, wounding their

hands,

getting sunstrokes, and whiltlows, and sprains, and disabling

themselves in

some way. L.-----, with her little medicine chest and her roll of lint and

bandages,

soon had a small but steady practice, and might have been seen about

the lower

deck most mornings after breakfast, repairing these damaged Alis and

Hassans.

It was well for them that we carried “an experienced

surgeon,” for they were

entirely helpless and despondent when hurt, and ignorant of the

commonest

remedies. Nor is this helplessness confined to natives of the sailor

and fellâh

class. The provincial proprietors and officials are to the full as

ignorant,

not only of the uses of such simple things as poultices or wet

compresses, but

of the most elementary laws of health. Doctors there are none south of

Cairo;

and such is the general mistrust of State medicine, that when, as in

the case

of any widely spread epidemic, a medical officer is sent up the river

by order

of the Government, half the people are said to conceal their sick,

while the

other half reject the remedies prescribed for them. Their trust in the

skill of

the passing European is, on the other hand, unbounded. Appeals for

advice and

medicine were constantly being made to us by both rich and poor; and

there was

something very pathetic in the simple faith with which they accepted

any little

help we were able to give them. Meanwhile L.-----’s medical

reputation, being

confirmed by a few simple cures, rose high among the crew. They called

her the

Hakîm Sitt (the Doctor-lady); obeyed her directions and swallowed

her medicines

as reverently as if she were the college of surgeons personified; and

showed

their gratitude in all kinds of pretty, child-like ways – singing

her favorite

Arab song as they ran beside her donkey – searching for

sculptured fragments

whenever there were ruins to be visited – and constantly bringing

her little

gifts of pebbles and wild flowers. Above

Siût, the picturesqueness of the river is confined for the most

part to the

eastern bank. We have almost always a near range of mountains on the

Arabian

side, and a more distant chain on the Libyan horizon. Gebel Sheik el

Raáineh

succeeds to Gebel Abufayda, and is followed in close succession by the

cliffs

of Gow, of Gebel Sheik el Hereedee, of Gebel Ayserat and Gebel

Tûkh – all

alike rigid in strongly-marked beds of level limestone strata;

flat-topped and

even, like lines of giant ramparts; and more or less pierced with

orifices

which we know to be tombs, but which look like loopholes from a

distance. Flying

before the wind with both sails set, we see the rapid panorama unfold

itself

day after day, mile after mile, hour after hour. Villages, palm-groves,

rock-cut sepulchres, flit past and are left behind. To-day we enter the

region

of the dôm palm. To-morrow we pass the map-drawn limit of the

crocodile. The

cliffs advance, recede, open away into desolate-looking valleys, and

show faint

traces of paths leading to excavated tombs on distant heights. The

headland

that looked shadowy in the distance a couple of hours ago, is reached

and

passsed. The cargo-boat on which we have been gaining all the morning

is

outstripped and dwindling in the rear. Now we pass a bold bluff

sheltering a

sheykh’s tomb and a solitary dôm palm – now an

ancient quarry from which the

stone has been cut out in smooth masses, leaving great halls, and

corridors,

and stages in the mountain side. At Gow,1 the scene of an

insurrection headed by a crazy dervish some ten years ago, we see, in

place of

a large and populous village, only a tract of fertile corn-ground, a

few ruined

huts, and a group of decapitated palms. We are now skirting Gebel Sheik el

Hereedee; here bordered by a rich margin of cultivated flat; yonder

leaving space

for scarce a strip of roadway between the precipice and the river. Then

comes

Raáineh, a large village of square mud towers, lofty and

battlemented, with

string-courses of pots for the pigeons – and later on, Girgeh,

once the capital

town of Middle Egypt, where we put in for half an hour to post and

inquire for

letters. Here the Nile is fast eating away the bank and carrying the

town by

storm. A ruined mosque with pointed arches, roofless cloisters, and a

leaning

column that must surely have come to the ground by this time, stands

just above

the landing-place. A hundred years ago, it lay a quarter of a mile from

the

river; ten years ago it was yet perfect; after a few more inundations

it will

be swept away. Till that time comes, however, it helps to make Girgeh

one of

the most picturesque towns in Egypt. At Farshût

we see the sugar-works in active operation – smoke pouring from

the tall

chimneys; steam issuing from the traps in the basement; cargo-boats

unlading

fresh sugar-cane against the bank; heavily-burdened Arabs transporting

it to

the factory; bullock-trucks laden with cane-leaf for firing. A little

higher

up, at Sahîl Bajûra on the opposite side of the river, we

find the bank strewn

for full a quarter of a mile with sugar-cane en masse. Hundreds

of

camels are either arriving laden with it, or going back for more

– dozens of

cargo-boats are drawn up to receive it – swarms of brown

fellâheen are stacking

it on board for unshipment again at Farshût. The camels snort and

growl; the

men shout; the overseers, in blue-fringed robes and white turbans,

stalk to and

fro, and keep the work going. The mountains here recede so far as to be

almost

out of sight, and a plain rich in sugar-cane and date-palms widens out

between

them and the river. And now

the banks are lovely with an unwonted wealth of verdure. The young corn

clothes

the plain like a carpet, while the yellow-tasselled mimosa, the

feathery

tamarisk, the dôm and date palm, and the spreading sycamore-fig,

border the

towing-path like garden trees beside a garden walk. Farther on

still, when all this greenery is left behind and the banks have again

become

flat and bare, we see to our exceeding surprise what seems to be a very

large

grizzled ape perched on the top of a dust-heap on the western bank. The

creature

is evidently quite tame, and sits on his haunches in just that chilly,

melancholy posture that the chimpanzee is wont to assume in his cage at

the

Zoological Gardens. Some six or eight Arabs, one of whom has dismounted

from

his camel for the purpose, are standing round and staring at him, much

as the

British public stands round and stares at the specimen in the

Regent’s Park.

Meanwhile a strange excitement breaks out among our crew. They crowd to

the

side; they shout; they gesticulate; the captain salaams; the steersman

waves

his hand; all eyes are turned towards the shore. “Do you

see Sheik Selîm?” cries Talhamy breathlessly, rushing up

from below. “There he

is! Look at him! That is Sheik Selîm!” And so we

find out that it is not a monkey but a man – and not only a man,

but a saint.

Holiest of the holy, dirtiest of the dirty, white-pated, white-bearded,

withered, bent, and knotted up, is the renowned Sheik Selîm

– he who, naked

and unwashed, has sat on that same spot every day through summer heat

and

winter cold for the last fifty years; never providing himself with food

or

water; never even lifting his hand to his mouth; depending on charity

not only

for his food but for his feeding! He is not nice to look at, even by

this dim

light, and at this distance; but the sailors think him quite beautiful,

and

call aloud to him for his blessing as we go by. “It is not

by our own will that we sail past, O father!” they cry.

“Fain would we kiss thy

hand; but the wind blows and the mérkeb (boat) goes and we have

no power to

stay!” But Sheik

Selîm neither lifts his head nor shows any sign of hearing, and

in a few

minutes the mound on which he sits is left behind in the gloaming. At How,

where the new town is partly built on the mounds of the old (Diospolis

Parva),

we next morning saw the natives transporting small boat-loads of

ancient

brick-rubbish to the opposite side of the river, for the purpose of

manuring

those fields from which the early durra crop had just been gathered in.

Thus,

curiously enough, the mud left by some inundation of two or three

thousand

years ago comes at last to the use from which it was then diverted, and

is

found to be more fertilising than the new deposit. At Kasr es Sayd, a

little

farther on, we came to one of the well-known “bad bits”

– a place where the bed

of the river is full of sunken rocks, and sailing is impossible. Here

the men

were half the day punting the dahabeeyah over the dangerous part, while

we

grubbed among the mounds of what was once the ancient city of

Chenoboscion.

These remains, which cover a large superficial area and consist

entirely of

crude brick foundations, are very interesting, and in good

preservation. We

traced the ground-plans of several houses; followed the passages by

which they

were separated; and observed many small arches which seemed built on

too small

a scale for doors or windows, but for which it was difficult to account

in any

other way. Brambles and weeds were growing in these deserted

enclosures; while

rubbish-heaps, excavated pits, and piles of broken pottery divided the

ruins

and made the work of exploration difficult. We looked in vain for the

dilapidated quay and sculptured blocks mentioned in Wilkinson’s "General

View

of Egypt;" but if the foundation stones of the sugar-factory close

against

the mooring-place could speak, they would no doubt explain the mystery.

We saw

nothing, indeed, to show that Chenoboscion had contained any stone

structures

whatever, save the broken shaft of one small granite column. The

village of Kasr es Syad consists of a cluster of mud huts and a sugar

factory;

but the factory was idle that day, and the village seemed half

deserted. The

view here is particularly fine. About a couple of miles to the

southward, the

mountains, in magnificent procession, came down again at right angles

to the

river, and thence reach away in long ranges of precipitous headlands.

The

plain, terminating abruptly against the foot of this gigantic barrier,

opens

back eastward to the remotest horizon – an undulating sea of

glistening sand, bordered

by a chaotic middle distance of mounded ruins. Nearest of all, a narrow

foreground of cultivated soil, green with young crops and watered by

frequent

shâdûfs, extends along the river-side to the foot of the

mountains. A sheykh’s

tomb shaded by a single dôm palm is conspicuous on the bank;

while far away,

planted amid the solitary sands, we see a large Coptic convent with

many

cupolas; a cemetery full of Christian graves; and a little oasis of

date palms

indicating the presence of a spring. The chief

interest of this scene, however, centres in the ruins; and these

– looked upon

from a little distance, blackened, desolate, half-buried, obscured

every now

and then, when the wind swept over them, by swirling clouds of dust

– reminded

us of the villages, we had seen not two years before, half-overwhelmed

and yet

smoking, in the midst of a lava-torrent below Vesuvius. We now had

the full moon again, making night more beautiful than day. Sitting on

deck for

hours after the sun had gone down, when the boat glided gently on with

half-filled sail and the force of the wind was spent, we used to wonder

if in

all the world there was another climate in which the effect of

moonlight was so

magical. To say that every object far or near was visible as distinctly

as by

day, yet more tenderly, is to say nothing. It was not only form that

was

defined; it was not only light and shadow that were vivid – it

was colour that

was present. Colour neither deadened or changed; but softened, glowing,

spiritualised. The amber sheen of the sand-island in the middle of the

river,

the sober green of the palm-grove, the little lady’s

turquoise-coloured hood,

were clear to the sight and relatively true in tone. The oranges showed

through

the bars of the crate like nuggets of pure gold. L-----’s crimson

shawl glowed with

a warmer dye than it ever wore by day. The mountains were flushed as if

in the

light of sunset. Of all the natural phenomena that we beheld in the

course of

the journey, I remember none that surprised us more than this. We could

scarcely believe at first that it was not some effect of afterglow, or

some

miraculous aurora of the East. But the sun had nothing to do with that

flush

upon the mountains. The glow was in the stone, and the moonlight but

revealed

the local colour. For some

days before they came in sight, we had been eagerly looking for the

Theban

hills; and now, after a night of rapid sailing, we woke one morning to

find the

sun rising on the wrong side of the boat, the favourable wind dead

against us,

and a picturesque chain of broken peaks upon our starboard bow. By

these signs

we knew that we must have come to the great bend in the river between

How and

Keneh, and that these new mountains, so much more varied in form than

those of

Middle Egypt, must be the mountains behind Denderah. They seemed to lie

upon

the eastern bank, but that was an illusion which the map disproved, and

which

lasted only till the great corner was fairly turned. To turn that

corner,

however, in the teeth of wind and current, was no easy task, and cost

us two

long days of hard tracking. At a point

about ten miles below Denderah, we saw some thousands of

fellâheen at work amid

clouds of sand upon the embankments of a new canal. They swarmed over

the

mounds like ants, and the continuous murmur of their voices came to us

across

the river like the humming of innumerable bees. Others, following the

path

along the bank, were pouring towards the spot in an unbroken stream.

The Nile

must here be nearly half a mile in breadth; but the engineers in

European dress,

and the overseers with long sticks in their hands, were plainly

distinguishable

by the help of a glass. The tents in which these officials were camping

out

during the progress of the work gleamed white among the palms by the

river-side. Such scenes must have been common enough in the old days

when a

conquering Pharaoh, returning from Libya or the land of Kush, set his

captives

to raise a dyke, or excavate a lake, or quarry a mountain. The

Israelites

building the massive walls of Pithom and Rameses with bricks of their

own

making, must have presented exactly such a spectacle. That we

were witnessing a case of forced labour, could not be doubted. Those

thousands

yonder had most certainly been drafted off in gangs from hundreds of

distant

villages, and were but little better off, for the time being, than the

captives

of the ancient empire. In all cases of forced labour under the present régime,

however, it seems that the labourer is paid, though very

insufficiently, for

his unwilling toil; and that his captivity only lasts so long as the

work for

which he has been pressed remains in progress. In some cases the term

of

service is limited to three or four months, at the end of which time

the men

are supposed to be returned in barges towed by government steam-tugs.

It too

often happens, nevertheless, that the poor souls are left to get back

how they

can; and thus many a husband and father either perishes by the way, or

is

driven to take service in some village far from home. Meanwhile his

wife and

children, being scantily supported by the Sheik el Beled, fall into a

condition of semi-serfdom; and his little patch of ground, left

untilled

through seed-time and harvest, passes after the next inundation into

the hands

of a stranger. But there

is another side to this question of forced labour. Water must be had in

Egypt,

no matter at what cost. If the land is not sufficiently irrigated the

crops

fail and the nation starves. Now, the frequent construction of canals

has from

immemorial time been reckoned among the first duties of an Egyptian

ruler; but

it is a duty which cannot be performed without the willing or unwilling

co-operation of several thousand workmen. Those who are best acquainted

with

the character and temper of the fellâh maintain the hopelessness

of looking to

him for voluntary labour of this description. Frugal, patient, easily

contented

as he is, no promise of wages, however high, would tempt him from his

native

village. What to him are the needs of a district six or seven hundred

miles

away? His own shâdûf is enough for his own patch, and so

long as he can raise

his three little crops a year, neither he nor his family will starve.

How,

then, are these necessary public works to be carried out, unless by

means of

the corvée? M. About has put an ingenious summary of

this “other-side”

argument into the mouth of his ideal fellâh. “It is not the

Emperor,” says

Ahmed to the Frenchman, “who causes the rain to descend upon your

lands; it is

the west wind – and the benefit thus conferred upon you exacts no

penalty of

manual labour. But in Egypt, where the rain from heaven falls scarcely

three

times in the year, it is the prince who supplies its place to us by

distributing the waters of the Nile. This can only be done by the work

of men’s

hands; and it is therefore to the interest of all that the hands of all

should

be at his disposal.” We

regarded it, I think, as an especial piece of good fortune, when we

found

ourselves becalmed next day within three or four miles of Denderah.

Abydos

comes first in order according to the map; but then the Temples lie

seven or

eight miles from the river, and as we happened just thereabouts to be

making

some ten miles an hour, we put off the excursion till our return. Here,

however, the ruins lay comparatively near at hand, and in such a

position that

we could approach them from below and rejoin our dahabeeyah a few miles

higher

up the river. So, leaving Reïs Hassan to track against the

current, we landed

at the first convenient point, and finding neither donkeys nor guides

at hand,

took an escort of three or four sailors, and set off on foot. The way

was long, the day was hot, and we had only the map to go by. Having

climbed the

steep bank and skirted an extensive palm-grove, we found ourselves in a

country

without paths or roads of any kind. The soil, squared off as usual like

a

gigantic chess-board, was traversed by hundreds of tiny water-channels,

between

which we had to steer our course as best as we could. Presently the

last belt

of palms was passed – the plain, green with young corn and level

as a lake,

widened out to the front of the mountains – and the temple,

islanded in that

sea of rippling emerald, rose up before us upon its platform of

blackened

mounds. It was

still full two miles away; but it looked enormous – showing from

this distance

as a massive, low-browed, sharply defined mass of dead-white masonry.

The walls

sloped in slightly towards the top; and the façade appeared to

be supported on

eight square piers, with a large doorway in the centre. If sculptured

ornament,

or cornice, or pictured legend enriched those walls, we were too far

off to

distinguish them. All looked strangely naked and solemn – more

like a tomb than

a temple. Nor was

the surrounding scene less deathlike in its solitude. Not a tree, not a

hut, not

a living form broke the green monotony of the plain. Behind the Temple,

but

divided from it by a farther space of mounded ruins, rose the mountains

–

pinky, aerial, with sheeny sand-drifts heaped in the hollows of their

bare

buttresses, and spaces of soft blue shadow in their misty chasms. Where

the

range receded, a long vista of glittering desert opened to the Libyan

horizon. Then as we

drew nearer, coming by and by to a raised causeway which apparently

connected

the mounds with some point down by the river, the details of the Temple

gradually emerged into distinctness. We could now see the curve and

under-shadow of the cornice; and a small object in front of the

façade which

looked at first sight like a monolithic altar, resolved itself into a

massive gateway

of the kind known as a single pylon. Nearer still, among some low

outlying

mounds, we came upon fragments of sculptured capitals and mutilated

statues

half-buried in rank grass – upon a series of stagnant nitre-tanks

and deserted

workshops – upon the telegraph poles and wires which here come

striding along

the edge of the desert and vanish southward with messages for Nubia and

the

Soudan. Egypt is

the land of nitre. It is found wherever a crude-brick mound is

disturbed or an

antique stone structure demolished. The Nile mud is strongly

impregnated with

it; and in Nubia we used to find it lying in thick talc-like flakes

upon the

surface of rocks far above the present level of the inundation. These

tanks at

Denderah had been sunk, we were told, when the great Temple was

excavated by

Abbas Pasha more than twenty years ago. The nitre then found was

utilised out

of hand; washed and crystallised in the tanks; and converted into

gunpowder in

the adjacent workshops. The telegraph wires are more recent intruders,

and the

work of the khedive; but one longed to put them out of sight, to pull

down the

gunpowder sheds, and to fill up the tanks with débris. For what

had the arts of

modern warfare or the wonders of modern science to do with Hathor, the

Lady of

Beauty and the Western Shades, the Nurse of Horus, the Egyptian

Aphrodite, to

whom yonder mountain of wrought stone and all these wastes were sacred?

We were by

this time near enough to see that the square piers of the façade

were neither

square nor piers, but huge round columns with human-headed capitals;

and that

the walls, instead of being plain and tomb-like, were covered with an

infinite

multitude of sculptured figures. The pylon – rich with

inscriptions and

bas-reliefs, but disfigured by myriads of tiny wasps’ nests, like

clustered

mud-bubbles – now towered high above our heads, and led to a

walled avenue cut

direct through the mounds, and sloping downwards to the main entrance

of the temple. Not, however, till we stood immediately under those ponderous columns, looking down upon the paved floor below and up to the huge cornice that projected overhead like the crest of an impending wave, did we realise the immense proportions of the building. Lofty as it looked from a distance, we now found that it was only the interior that had been excavated, and that not more than two-thirds of its actual height were visible above the mounds. The level of the avenue was, indeed, at its lowest part full twenty feet above that of the first great hall; and we had still a steep temporary staircase to go down before reaching the original pavement.

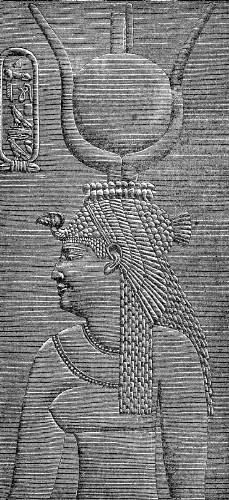

Among

those which escaped, however, is the famous external bas-relief of

Cleopatra on

the back of the temple. This curious sculpture is now banked up with

rubbish

for its better preservation, and can no longer be seen by travellers.

It was,

however, admirably photographed some years ago by Signor Beati; which

photograph

is faithfully reproduced in the annexed engraving. Cleopatra is here

represented with a headdress combining the attributes of three

goddesses;

namely the Vulture of Maut (the head of which is modelled in a masterly

way),

the horned disc of Hathor, and the throne of Isis. The falling mass

below the

headdress is intended to represent hair dressed according to the

Egyptian

fashion, in an infinite number of small plaits, each finished off with

an

ornamental tag. The women of Egypt and Nubia wear their hair so to this

day,

and unplait it, I am sorry to say, not oftener than once in every eight

or ten

weeks. The Nubian girls fasten each separate tail with a lump of Nile

mud

daubed over with yellow ochre; but Queen Cleopatra’s silken

tresses were

probably tipped with gilded wax or gum. It is

difficult to know where decorative sculpture ends and portraiture

begins in a

work of this epoch. We cannot even be certain that a portrait was

intended;

though the introduction of the royal oval in which the name of

Cleopatra

(Klaupatra) is spelt with its vowel sounds in full, would seem to point

that

way. If it is a portrait, then large allowance must be made for

conventional

treatment. The fleshiness of the features and the intolerable simper

are common

to every head of the Ptolemaic period. The ear, too, is pattern work,

and the

drawing of the figure is ludicrous. Mannerism apart, however, the face

wants

for neither individuality nor beauty. Cover the mouth, and you have an

almost

faultless profile. The chin and throat are also quite lovely; while the

whole

face, suggestive of cruelty, subtlety, and voluptuousness, carries with

it an

indefinable impression not only of portraiture, but of likeness. It is not

without something like a shock that one first sees the unsightly havoc

wrought

upon the Hathor-headed columns of the façade at Denderah. The

massive folds of

headgear are there; the ears, erect and pointed like those of a heifer,

are

there; but of the benignant face of the goddess not a feature remains.

Ampère,

describing these columns in one of his earliest letters from Egypt,

speaks of

them as being still “brilliant with colours that time had had no

power to

efface.” Time, however, must have been unusually busy during the

thirty years

that have gone by since then; for though we presently found several

instances

of painted bas-reliefs in the small inner chambers, I do not remember

to have

observed any remains of colour (save here and there a faint trace of

yellow

ochre) on the external decorations. Without,

all was sunshine and splendour; within, all was silence and mystery. A

heavy,

death-like smell, as of long-imprisoned gases, met us on the threshold.

By the

half-light that strayed in through the portico, we could see vague

outlines of

a forest of giant columns rising out of the gloom below and vanishing

into the

gloom above. Beyond these again appeared shadowy vistas of successive

halls

leading away into depths of impenetrable darkness. It required no great

courage

to go down those stairs and explore those depths with a party of

fellow-travellers; but it would have been a gruesome place to venture

into

alone. Seen from

within, the portico shows as a vast hall, fifty feet in height and

supported on

twenty-four Hathor-headed columns. Six of these, being engaged in the

screen,

form part of the façade, and are the same upon which we have

been looking from

without. By degrees, as our eyes become used to the twilight, we see

here and

there a capital which still preserves the vague likeness of a gigantic

female

face; while, dimly visible on every wall, pillar, and doorway, a

multitude of

fantastic forms – hawk-headed, ibis-headed, cow-headed, mitred,

plumed, holding

aloft strange emblems, seated on thrones, performing mysterious rites

– seem to

emerge from their places, like things of life. Looking up to the

ceiling, now

smoke-blackened and defaced, we discover elaborate paintings of

scarabæi,

winged globes, and zodiacal emblems divided by borders of intricate

Greek

patterns, the prevailing colours of which are verditer and chocolate.

Bands of

hieroglyphic inscriptions, of royal ovals, of Hathor heads, of mitred

hawks, of

lion-headed chimeras, of divinities and kings in bas-relief, cover the

shafts

of the great columns from top to bottom; and even here, every

accessible face, however

small, has been laboriously mutilated. Bewildered

at first sight of these profuse and mysterious decorations, we wander

round and

round; going on from the first hall to the second, from the second to

the

third; and plunging into deeper darkness at every step. We have been

reading

about these gods and emblems for weeks past – we have studied the

plan of the temple beforehand; yet now that we are actually here, our book

knowledge goes

for nothing, and we feel as hopelessly ignorant as if we had been

suddenly

landed in a new world. Not till we have got over this first feeling of

confusion – not till, resting awhile on the base of one of the

columns, we

again open out the plan of the building, do we begin to realise the

purport of

the sculptures by which we are surrounded. The

ceremonial of Egyptian worship was essentially processional. Herein we

have the

central idea of every temple, and the key to its construction. It was

bound to

contain store-chambers in which were kept vestments, instruments,

divine emblems,

and the like; laboratories for the preparation of perfumes and

unguents;

treasuries for the safe custody of holy vessels and precious offerings;

chambers for the reception and purification of tribute in kind; halls

for the

assembling and marshalling of priests and functionaries; and, for

processional

purposes, corridors, staircases, courtyards, cloisters, and vast

enclosures

planted with avenues of trees and surrounded by walls which hedged in

with

inviolable secrecy the solemn rites of the priesthood. In this

plan, it will be seen, there is no provision made for anything in the

form of

public worship; but then an Egyptian Temple was not a place for public

worship.

It was a treasure-house, a sacristy, a royal oratory, a place of

preparation,

of consecration, of sacerdotal privacy. There, in costly shrines, dwelt

the

divine images. There they were robed and unrobed; perfumed with

incense;

visited and worshipped by the King. On certain great days of the

kalendar, as

on the occasion of the festival of the new year, or the panegyrics of

the local

gods, these images were brought out, paraded along the corridors of the

temple,

carried round the roof, and borne with waving of banners, and chanting

of

hymns, and burning of incense, through the sacred groves of the

enclosure.

Probably none were admitted to these ceremonies save persons of royal

or

priestly birth. To the rest of the community, all that took place

within those

massy walls was enveloped in mystery. It may be questioned, indeed,

whether the

great mass of people had any kind of personal religion. They may not

have been

rigidly excluded from the temple-precincts, but they seem to have been

allowed

no participation in the worship of the gods. If now and then, on high

festival

days, they beheld the sacred bark of the deity carried in procession

round the

temenos, or caught a glimpse of moving figures and glittering ensigns

in the

pillared dusk of the Hypostyle Hall, it was all they ever beheld of the

solemn

services of their church. The temple

of Denderah consists of a portico; a hall of entrance; a hall of

assembly; a

third hall, which may be called the hall of the sacred boats; one small

ground

floor chapel; and upwards of twenty side chambers of various sizes,

most of

which are totally dark. Each one of these halls and chambers bears the

sculptured record of its use. Hundreds of tableaux in bas-relief,

thousands of

elaborate hieroglyphic inscriptions, cover every foot of available

space on

wall and ceiling and soffit, on doorway and column, and on the

lining-slabs of

passages and staircases. These precious texts contain, amid much that

is

mystical and tedious, an extraordinary wealth of indirect history. Here

we find

programmes of ceremonial observances; numberless legends of the gods;

chronologies of Kings with their various titles; registers of weights

and

measures; catalogues of offerings; recipes for the preparation of oils

and

essences; records of repairs and restorations done to the Temple;

geographical

lists of cities and provinces; inventories of treasure, and the like.

The hall

of assembly contains a kalendar of festivals, and sets forth with

studied

precision the rites to be performed on each recurring anniversary. On

the

ceiling of the portico we find an astronomical zodiac; on the walls of

a small

temple on the rood, the whole history of the resurrection of Osiris,

together

with the order of prayer for the twelve hours of the night, and a

kalendar of

the festivals of Osiris in all the principal cities of Upper and Lower

Egypt.

Seventy years ago, these inscriptions were the puzzle and despair of

the

learned; but since modern science has plucked out the heart of its

mystery, the

whole Temple lies before us an open volume filled to overflowing with

strange

and quaint and heterogeneous matter – a Talmud in sculptured

stone.4 Given

such

help as Mariette’s handbook affords, one can trace out most of

these curious

things, and identify the uses of every hall and chamber throughout the

building. The King, in the double character of Pharaoh and high priest,

is the

hero of every sculptured scene. Wearing sometimes the truncated crown

of Lower

Egypt, sometimes the helmet-crown of Upper Egypt, and sometimes the

pschent,

which is a combination of both, he figures in every tableau and heads

every

procession. Beginning with the sculptures of the portico, we see him

arrive,

preceded by his five royal standards. He wears his long robe; his

sandals are

on his feet; he carries his staff in his hand. Two goddesses receive

him at the

door and conduct him into the presence of Thoth, the ibis-headed, and

Horus,

the hawk-headed, who pour upon him a double stream of the waters of

life. Thus

purified, he is crowned by the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, and

by them

consigned to the local deities of Thebes and Heliopolis, who usher him

into the

supreme presence of Hathor. He then presents various offerings and

recites

certain prayers; whereupon the goddess promises him length of days,

everlasting

renown, and other good things. We next see him, always with the same

smile and

always in the same attitude, doing homage to Osiris, to Horus and other

divinities. He presents them with flowers, wine, bread, incense; while

they in

return promise him life, joy, abundant harvests, victory, and the love

of his

people. These pretty speeches – chefs d’oeuvre of

diplomatic style and models

of elegant flattery – are repeated over and over again in scores

of

hieroglyphic groups. Mariette, however, sees in them something more

than the

language of the court grafted upon the language of the hierarchy; he

detects

the language of the schools, and discovers in the utterances here

ascribed to

the King and the gods a reflection of that contemporary worship of the

beautiful, the good, and the true, which characterised the teaching of

the

Alexandrian Museum.5 Passing on

from the portico to the hall of assembly, we enter a region of still

dimmer

twilight, beyond which all is dark. In the side-chambers, where the

heat is

intense and the atmosphere stifling, we can see only by the help of

lighted

candles. These rooms are about twenty feet in length; separate, like

prison

cells; and perfectly dark. The sculptures which cover the walls are,

however,

as numerous as those in the outer halls, and indicate in each instance

the

purpose for which the room was designed. Thus in the laboratories we

find

bas-reliefs of flasks and vases, and figures carrying perfume-bottles

of the

familiar aryballos form; in the tribute-chambers, offerings of

lotus-lilies,

wheat sheaves, maize, grapes, and pomegranates; in the oratories of

Isis, Amen,

and Sekhet, representations of these divinities enthroned, and

receiving the

homage of the King; while in the treasury, both king and queen appear

laden

with precious gifts of caskets, necklaces, pectoral ornaments,

sistrums, and

the like. It would seem that the image-breakers had no time to spare

for these

dark cells; for here the faces and figures are unmutilated, and in some

places

even the original colouring remains in excellent preservation. The

complexion

of the goddesses, for instance, is painted of a light buff; the

King’s skin is

dark-red; that of Amen, blue. Isis wears a rich robe of the well-known

Indian

pine-pattern; Sekhet figures in a many-coloured garment curiously

diapered;

Amen is clad in red and green chain armour. The skirts of the goddesses

are

inconceivably scant; but they are rich in jewellery, and their

headdresses,

necklaces, and bracelets are full of minute and interesting detail. In

one of

the four oratories dedicated to Sekhet, the king is depicted in the act

of offering

a pectoral ornament of so rich and elegant a design that, had there

been time

and daylight, the writer would fain have copied it. In the

centre room at the extreme end of the Temple, exactly opposite the main

entrance, lies the oratory of Hathor. This dark chamber, into which no

ray of

daylight has ever penetrated, contains the sacred niche, the Holy of

Holies, in

which was kept the great Golden Sistrum of the goddess. The king alone

was

privilieged to take out that mysterious emblem. Having done so, he

enclosed it

in a costly shrine, covered it with a thick veil, and placed it in one

of the

sacred boats of which we find elaborate representations sculptured on

the walls

of the hall in which they were kept. These boats, which were

constructed of cedar-wood,

gold, and silver, were intended to be hoisted on wrought poles, and so

carried

in procession on the shoulders of the priests. The niche is still there

– a

mere hole in the wall, some three feet square and about eight feet from

the

ground. Thus, candle

in hand, we make the circuit of these outer chambers. In each doorway,

besides

the place cut out for the bolt, we find a circular hole drilled above

and a

quadrant-shaped hollow below, where once upon a time the pivot of the

door

turned in its socket. The paved floors, torn up by treasure-seekers,

are full

of treacherous holes and blocks of broken stone. The ceilings are very

lofty.

In the corridors a dim twilight reigns; but all is pitch-dark beyond

these

gloomy thresholds. Hurrying along by the light of a few flaring

candles, one

cannot but feel oppressed by the strangeness and awfulness of the

place. We

speak with bated breath, and even our chattering Arabs for once are

silent. The

very air tastes as if it had been imprisoned here for centuries. Finally,

we take the staircase on the northern side of the temple, in order to

go up to

the roof. Nothing that we have yet seen surprises and delights us so

much, I

think, as this staircase. We had

hitherto been tracing in their order all the preparations for a great

religious

ceremony. We have seen the king enter the temple; undergo the

symbolical

purification; receive the twofold crown; and say his prayers to each

divinity

in turn. We have followed him into the laboratories, the oratories, and

the

Holy of Holies. All that he has yet done, however, is preliminary. The

procession is yet to come, and here we have it. Here, sculptured on the

walls

of this dark staircase, the crowning ceremony of Egyptian worship is

brought

before our eyes in all its details. Here, one by one, we have the

standard-bearers, the hierophants with the offerings, the priests, the

whole

long, wonderful procession, with the king marching at its head. Fresh

and

uninjured as if they had but just left the hand of the sculptor, these

figures –

each in his habit as he lived, each with his foot upon the step –

mount with us

as we mount, and go beside us all the way. Their attitudes are so

natural,

their forms so roundly cut, that one could almost fancy them in motion

as the

lights flicker by. Surely there must be some one weird night in the

year when

they step out from their places, and take up the next verse of their

chanted

hymn, and, to the sound of instruments long mute and songs long silent,

pace

the moonlit roof in ghostly order! The sun is

already down and the crimson light has faded, when at length we emerge

upon

that vast terrace. The roofing-stones are gigantic. Striding to and fro

over

some of the biggest, our Idle Man finds several that measure seven

paces in

length by four in breadth. In yonder distant corner, like a little

stone lodge

in a vast courtyard, stands a small temple supported on Hathor-headed

columns;

while at the eastern end, forming a second and loftier stage, rises the

roof of

the portico. Meanwhile,

the afterglow is fading. The mountains are yet clothed in an atmosphere

of

tender half-light; but mysterious shadows are fast creeping over the

plain, and

the mounds of the ancient city lie at our feet, confused and tumbled,

like the

waves of a dark sea. How high it is here – how lonely – how

silent! Hark that

thin plaintive cry! It is the wail of a night-wandering jackal. See how

dark it

is yonder, in the direction of the river! Quick, quick! We have

lingered too

long. We must be gone at once; for we are already benighted. We ought

to have gone down by way of the opposite staircase (which is lined with

sculptures of the descending procession) and out through the temple;

but there

is no time to do anything but scramble down by a breach in the wall at

a point

where the mounds yet lie heaped against the south side of the building.

And now

the dusk steals on so rapidly that before we reach the bottom we can

hardly see

where to tread. The huge side-wall of the portico seems to tower above

us to

the very heavens. We catch a glimpse of two colossal figures, one

lion-headed

and the other headless, sitting outside with their backs to the temple.

Then,

making with all speed for the open plain, we clamber over scattered

blocks and

among shapeless mounds. Presently night overtakes us. The mountains

disappear;

the Temple is blotted out; and we have only the faint starlight to

guide us. We

stumble on, however, keeping all close together; firing a gun every now

and

then, in the hope of being heard by those in the boats; and as

thoroughly and

undeniably lost as the babes in the wood. At last, just as some are beginning to knock up and all to despair, Talhamy fires his last cartridge. An answering shot replies from near by; a wandering light appears in the distance; and presently a whole bevy of dancing lanterns and friendly brown faces comes gleaming out from among a plantation of sugar-canes, to welcome and guide us home. Dear, sturdy, faithful little Reïs Hassan, honest Khalîfeh, laughing Salame, gentle Mehemet Ali, and Mûsa “black but comely” – they were all there. What a shaking of hands there was – what a gleaming of white teeth – what a shower of mutually unintelligible congratulations! For my own part, I may say with truth that I was never much more rejoiced at a meeting in my life. __________________________1 According

to the account given in her letters by Lady Duff Gordon, this dervish,

who had

acquired a reputation for unusual sanctity by repeating the name of

Allah 3000

times every night for three years, believed that he had by these means

rendered

himself invulnerable; and so, proclaiming himself the appointed Slayer

of

Antichrist, he stirred up a revolt among the villages bordering Gebel Sheik

Hereedee, instigated an attack on an English dahabeeyah, and brought

down upon

himself and all that country-side the swift and summary vengeance of

the government. Steamers with troops commanded by Fadl Pasha were

despatched up the

river; rebels were shot; villages sacked; crops and cattle confiscated.

The

women and children of the place were then distributed among the

neighbouring

hamlets; and Gow, which was as large a village as Luxor, ceased to

exist. The

dervish’s fate remained uncertain. He was shot, according to

some; and by

others it was said that he had escaped into the desert under the

protection of

a tribe of Bedouins. 2 Sir G.

Wilkinson states the total length of the temple to be 93 paces, or 220

feet;

and the width of the portico 50 paces. Murray gives no measurements;

neither

does Mariette Bey in his delightful little “Itineraire;”

neither does

Fergusson, nor Champollion, nor any other writer to whose works I have

had

access. 3 The names

of Augustus, Caligula, Tiberius, Domitian, Claudius, and Nero are found

in the

royal ovals; the oldest being those of Ptolemy XI, the founder of the

present

edifice, which was, however, rebuilt upon the site of a succession of

older

buildings, of which the most ancient dated back as far as the reign of

Khufu,

the builder of the great pyramid. This fact, and the still more

interesting

fact that the oldest structure of all was believed to belong to the

inconceivably remote period of the Horshesu, or

“followers of Horus” (i.e.

the petty chiefs, or princes, who ruled in Egypt before the foundation

of the

first monarchy), is recorded in the following remarkable inscription

discovered

by Mariette in one of the crypts constructed in the thickness of the

walls of

the present temple. The first text relates to certain festivals to be

celebrated in honour of Hathor, and states that all the ordained

ceremonies had

been performed by King Thothmes III (eighteenth dynasty) “in memory

of his mother,

Hathor of Denderah. And they found the great fundamental rules of

Denderah in

ancient writing, written on goat-skin in the time of the Followers of

Horus.

This was found in the inside of a brick wall during the reign of King

Pepi

(sixth dynasty).” In the same crypt, another and a more brief

inscriptions runs

thus: – “Great fundamental rule of Denderah. Restorations

done by Thothmes III,

according to what was found in ancient writing of the time of King

Khufu.”

Hereupon Mariette remarks – “The temple of Denderah is not,

then, one of the

most modern in Egypt, except in so far as it was constructed by one of

the

later Lagidæ. Its origin is literally lost in the night of

time.” See "Dendérah,

Description Générale," chap. i. pp.55, 56. 4 See

Mariette’s "Denderah," which contains the whole of these

multitudinous

inscriptions in 166 plates; also a selection of some of the most

interesting in

Brugsch and Dümichen’s "Recueil de Monuments Egyptiens"

and "Geographische

Inschriften," 1862, 1863, 1865 and 1866. 5 Hathor (or

more correctly Hat-hor, i.e. the abode of Horus) is not merely

the

Aphrodite of ancient Egypt: she is the pupil of the eye of the Sun: she

is the

goddess of that beneficent planet whose rising heralds the waters of

the

inundation; she represents the eternal youth of nature, and is the

direct

personification of the beautiful. She is also goddess of truth.

“I offer the truth to thee, O Goddess of Denderah!” says the king, in one of

the

inscriptions of the sanctuary of the Sistrum; “for truth is thy

work, and thou

thyself art truth.” Lastly, her emblem is the Sistrum, and the

sound of the

Sistrum, according to Plutarch, was supposed to terrify and expel

Typhon (the

evil principle); just as in mediæval times the ringing of

church-bells was

supposed to scare Beelzebub and his crew. From this point of view, the

Sistrum

becomes typical of the triumph of good over evil. Mariette, in his

analysis of

the decorations and inscriptions of this temple, points out how the

builders were

influenced by the prevailing philosophy of the age, and how they veiled

the

Platonism of Alexandria beneath the symbolism of the ancient religion.

The

Hat-hor of Denderah was in fact worshipped in a sense unknown to the

Egyptians

of pre-Ptolemaic times. |