| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER

XII. PHILÆ. HAVING

been for so many days within easy reach of Philæ, it is not to be

supposed that

we were content till now with only an occasional glimpse of its towers

in the

distance. On the contrary, we had found our way thither towards the

close of

almost every day’s excursion. We had approached it by land from

the desert; by

water in the felucca; from Mahatta by way of the path between the

cliffs and

the river. When I add that we moored here for a night and the best part

of two

days on our way up the river, and again for a week when we came down,

it will

be seen that we had time to learn the lovely island by heart. The approach

by water is quite the most beautiful. Seen from the level of a small

boat, the

island, with its palms, its colonnades, its pylons, seems to rise out

of the

river like a mirage. Piled rocks frame it in on either side, and purple

mountains close up the distance. As the boat glides nearer between

glistening

boulders, those sculptured towers rise higher and ever higher against

the sky.

They show no sign of ruin or of age. All looks solid, stately, perfect.

One

forgets for the moment that anything is changed. If a sound of antique

chanting

were to be borne along the quiet air – if a procession of

white-robed priests

bearing aloft the veiled ark of the god, were to come sweeping round

between

the palms and the pylons – we should not think it strange. Most

travellers land at the end nearest the cataract; so coming upon the

principal

temple from behind, and seeing it in reverse order. We, however, bid

our Arabs

row round to the southern end, where was once a stately landing-place

with

steps down to the river. We skirt the steep banks, and pass close under

the

beautiful little roofless temple commonly known as Pharaoh’s Bed

– that temple

which has been so often painted, so often photographed, that every

stone of it,

and the platform on which it stands, and the tufted palms that cluster

about

it, have been since childhood as familiar to our mind’s eye as

the sphinx or

the pyramids. It is larger, but not one jot less beautiful than we had

expected. And it is exactly like the photographs. Still, one is

conscious of

perceiving a shade of difference too subtle for analysis; like the

difference

between a familiar face and the reflection of it in a looking-glass.

Anyhow,

one feels that the real Pharoah’s Bed will henceforth displace

the photographs

in that obscure mental pigeon-hole where till now one has been wont to

store

the well-known image; and that even the photographs have undergone some

kind of

change. And now

the corner is rounded; and the river widens away southwards between

mountains

and palm-groves; and the prow touches the débris of a ruined

quay. The bank is

steep here. We climb; and a wonderful scene opens before our eyes. We

are

standing at the lower end of a courtyard leading up to the propylons of

the

great t emple. The courtyard is irregular in shape, and enclosed on

either side

by covered colonnades. The colonnades are of unequal lengths and set at

different angles. One is simply a covered walk; the other opens upon a

row of

small chambers, like a monastic cloister opening upon a row of cells.

The roofing-stones

of these colonnades are in part displaced, while here and there a

pillar or a

capital is missing; but the twin towers of the propylon, standing out

in sharp

unbroken lines against the sky and covered with colossal sculptures,

are as

perfect, or very nearly as perfect, as in the days of the Ptolemies who

built

them. The broad

area between the colonnades is honeycombed with crude-brick

foundations;

vestiges of a Coptic village of early Christian time. Among these we

thread our

way to the foot of the principal propylon, the entire width of which is

120

feet. The towers measure 60 feet from base to parapet. These dimensions

are

insignificant for Egypt; yet the propylon, which would look small at

Luxor or

Karnak, does not look small at Philæ. The key-note here is not

magnitude, but

beauty. The island is small – that is to say it covers an area

about equal to

the summit of the Acropolis at Athens; and the scale of the buildings

has been

determined by the size of the island. As at Athens, the ground is

occupied by

one principal Temple of moderate size, and several subordinate Chapels.

Perfect

grace, exquisite proportion, most varied and capricious grouping, here

take the

place of massiveness; so lending to Egyptian forms an irregularity of

treatment

that is almost Gothic, and a lightness that is almost Greek. And now we

catch glimpses of an inner court, of a second propylon, of a pillared

portico

beyond; while, looking up to the colossal bas-reliefs above our heads,

we see

the usual mystic forms of kings and deities, crowned, enthroned,

worshipping

and worshipped. These sculptures, which at first sight looked not less

perfect

than the towers, prove to be as laboriously mutilated as those of

Denderah. The

hawk-head of Horus and the cow-head of Hathor have here and there

escaped

destruction; but the human-faced deities are literally “sans

eyes, sans nose,

sans ears, sans everything.” We enter

the inner court – an irregular quadrangle enclosed on the east by

an open

colonnade, on the west by a chapel fronted with Hathor-headed columns,

and on

the north and south sides by the second and first propylons. In this

quadrangle

a cloistral silence reigns. The blue sky burns above – the

shadows sleep below

– a tender twilight lies about our feet. Inside the chapel there

sleeps

perpetual gloom. It was built by Ptolemy Euergetes II, and is one of

that order

to which Champollion gave the name of Mammisi. It is a most curious

place,

dedicated to Hathor and commemorative of the nurture of Horus. On the

blackened

walls within, dimly visible by the faint light which struggles through

screen

and doorway, we see Isis, the wife and sister of Osiris, giving birth

to Horus.

On the screen panels outside we trace the story of his infancy,

education, and

growth. As a babe at the breast, he is nursed in the lap of Hathor, the

divine

foster-mother. As a young child, he stands at his mother’s knee

and listens to

the playing of a female harpist (we saw a bare-footed boy the other day

in

Cairo thrumming upon a harp of just the same shape, and with precisely

as many

strings); as a youth, he sows grain in honour of Isis, and offers a

jewelled

collar to Hathor. This Isis, with her long aquiline nose, thin lips,

and

haughty aspect, looks like one of the complimentary portraits so often

introduced

among the temple sculptures of Egypt. It may represent one of the two

Cleopatras wedded to Ptolemy Physcon. Two

greyhounds with collars round their necks are sculptured on the outer

wall of

another small chapel adjoining. These also look like portraits. Perhaps

they

were the favourite dogs of some high priest of Philæ. Close

against the greyhounds and upon the same wall-space, is engraven that

famous

copy of the inscription of the Rosetta Stone first observed here by

Lepsius in

A.D. 1843. It neither stands so high nor looks so illegible as

Ampère (with all

the jealousy of a Champollionist and a Frenchman) is at such pains to

make out.

One would have said that it was in a state of more than ordinarily good

preservation. As a

reproduction of the Rosetta decree, however, the Philæ version is

incomplete.

The Rosetta text, after setting forth with official pomposity the

victories and

munificence of the king, – Ptolemy V, the ever-living, the avenger of

Egypt, – concludes by ordaining that the record thereof shall be engraven in

hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek characters, and set up in all temples

of the

first, second, and third class throughout the empire. Broken and

battered as it

is, the precious black basalt1 of the British Museum

fulfils these

conditions. The three writings are there. But at Philæ, though

the original

hieroglyphic and demotic texts are reproduced almost verbatim, the

priceless

Greek transcript is wanting. It is provided for, as upon the Rosetta

Stone, in

the preamble. Space has been left for it at the bottom of the tablet.

We even

fancied we could here and there distinguish traces of red ink where the

lines

should come. But not one word of it has ever been cut into the surface

of the

stone. Taken by

itself, there is nothing strange in this omission; but taken in

connection with

a precisely similar omission in another inscription a few yards

distant, it

becomes something more than a coincidence. This

second inscription is cut upon the face of a block of living rock which

forms

part of the foundation of the easternmost tower of the second propylon.

Having

enumerated certain grants of land made to the Temple by PtolemiesVI and

VII, it concludes, like the first, by decreeing that this record

of the

royal bounty shall be engraven in the hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek:

that is

to say, in the ancient sacred writing of the priests, the ordinary

script of

the people, and the language of the Court. But here again the sculptor

has left

his work unfinished. Here again the inscription breaks off at the end

of the

demotic, leaving a blank space for the third transcript. This second

omission

suggests intentional neglect; and the motive for such neglect would not

be far

to seek. The tongue of the dominant race is likely enough to have been

unpopular

among the old noble and sacerdotal families; and it may well be that

the

priesthood of Philæ, secure in their distant, solitary isle,

could with

impunity evade a clause which their brethren of the Delta were obliged

to obey.

It does

not follow that the Greek rule was equally unpopular. We have reason to

believe

quite otherwise. The conqueror of the Persian invader was in truth the

deliverer of Egypt. Alexander restored peace to the country, and the

Ptolemies

identified themselves with the interests of the people. A dynasty which

not

only lightened the burdens of the poor but respected the privileges of

the

rich; which honoured the priesthood, endowed the temples, and compelled

the

Tigris to restore the spoils of the Nile, could scarcely fail to win

the suffrages

of all classes. The priests of Philæ might despise the language

of Homer while

honouring the descendants of Philip of Macedon. They could naturalise

the king.

They could disguise his name in hieroglyphic spelling. They could

depict him in

the traditional dress of the Pharaohs. They could crown him with the

double

crown, and represent him in the act of worshipping the gods of his

adopted

country. But they could neither naturalise nor disguise his language.

Spoken or

written, it was an alien thing. Carven in high places, it stood for a

badge of

servitude. What could a conservative hierarchy do but abhor, and, when

possible, ignore it? There are

other sculptures in this quadrangle which one would like to linger

over; as,

for instance, the capitals of the eastern colonnade, no two of which

are alike,

and the grotesque bas-reliefs of the frieze of the Mammisi. Of these, a

quasi-heraldic group, representing the sacred hawk sitting in the

centre of a

fan-shaped persea tree between two supporters, is one of the most

curious; the

supporters being on the one side a maniacal lion, and on the other a

Typhonian

hippopotamus, each grasping a pair of shears. Passing

now through the doorway of the second propylon, we find ourselves

facing the

portico – the famous painted portico of which we had seen so many

sketches that

we fancied we knew it already. That second-hand knowledge goes for

nothing,

however, in presence of the reality; and we are as much taken by

surprise as if

we were the first travellers to set foot within these enchanted

precincts. For here

is a place in which time seems to have stood as still as in that

immortal

palace where everything went to sleep for a hundred years. The

bas-reliefs on

the walls, the intricate paintings on the ceilings, the colours upon

the

capitals, are incredibly fresh and perfect. These exquisite capitals

have long

been the wonder and delight of travellers in Egypt. They are all

studied from

natural forms – from the lotus in bud and blossom, the papyrus,

and the palm.

Conventionalised with consummate skill, they are at the same time so

justly

proportioned to the height and girth of the columns as to give an air

of

wonderful lightness to the whole structure. But above all, it is with

the

colour – colour conceived in the tender and pathetic minor of

Watteau and

Lancret and Greuze – that one is most fascinated. Of those

delicate half-tones,

the facsimile in the “Grammar of Ornament” conveys not the

remotest idea. Every

tint is softened, intermixed, degraded. The pinks are coralline; the

greens are

tempered with verditer; the blues are of a greenish turquoise, like the

western

half of an autumnal evening sky. Later on,

when we returned to Philæ from the second cataract, the Writer

devoted the best

part of three days to making a careful study of a corner of this

portico;

patiently matching those subtle variations of tint, and endeavouring to

master

the secret of their combination.2 The

annexed woodcut can do no more than reproduce the forms. Architecturally,

this court is unlike any we have yet seen, being quite small, and open

to the

sky in the centre, like the atrium of a Roman house. The light thus

admitted

glows overhead, lies in a square patch on the ground below, and is

reflected

upon the pictured recesses of the ceiling. At the upper end, where the

pillars

stand two deep, there was originally an intercolumnar screen. The rough

sides

of the columns show where the connecting blocks have been torn away.

The

pavement, too, has been pulled up by treasure-seekers, and the ground

is strewn

with broken slabs and fragments of shattered cornice. These are

the only signs of ruin – signs traced not by the finger of time,

but by the

hand of the spoiler. So fresh, so fair is all the rest, that we are

fain to

cheat ourselves for a moment into the belief that what we see is work

not

marred, but arrested. Those columns, depend on it, are yet unfinished.

That

pavement is about to be relaid. It would not surprise us to find the

masons

here to-morrow morning, or the sculptor, with mallet and chisel,

carrying on

that band of lotus buds and bees. Far more difficult is it to believe

that they

all struck work for ever some two-and-twenty centuries ago. Here and

there, where the foundations have been disturbed, one sees that the

columns are

constructed of sculptured blocks, the fragments of some earlier Temple;

while,

at a height of about six feet from the ground, a Greek cross cut deep

into the

side of the shaft stamps upon each pillar the seal of Christian

worship. For the

Copts who choked the colonnades and courtyards with their hovels seized

also on

the temples. Some they pulled down for building material; others they

appropriated. We can never know how much they destroyed; but two large

convents

on the eastern bank a little higher up the river, and a small basilica

at the

north end of the island, would seem to have been built with the

magnificent

masonry of the southern quay, as well as with blocks taken from a

structure

which once occupied the south-eastern corner of the great colonnade. As

for

this beautiful painted portico, they turned it into a chapel. A little

rough-hewn niche in the east wall, and an overturned credence-table

fashioned

from a single block of limestone, mark the sight of the chancel. The

Arabs,

taking this last for a gravestone, have pulled it up, according to

their usual

practice, in search of treasure buried with the dead. On the front of

the

credence-table,3 and over the niche which some unskilled

but pious

hand has decorated with rude Byzantine carvings, the Greek cross is

again conspicuous.

The

religious history of Philæ is so curious that it is a pity it

should not find

an historian. It shared with Abydos and some other places the

reputation of

being the burial-place of Osiris. It was called “The Holy

Island.” Its very

soil was sacred. None might land upon its shores, or even approach them

too

nearly, without permission. To obtain that permission and perform the

pilgrimage to the tomb of the god, was to the pious Egyptian what the

Mecca

pilgrimage is to the pious Mussulman of to-day. The most solemn oath to

which

he could give utterance was “By Him who sleeps in

Philæ.” When and

how the island first came to be regarded as the resting-place of the

most

beloved of the gods does not appear; but its reputation for sanctity

seems to have

been of comparatively modern date. It probably rose into importance as

Abydos

declined. Herodotus, who is supposed to have gone as far as

Elephantine, made

minute enquiry concerning the river above that point; and he relates

that the cataract was in the occupation of “Ethiopian nomads.” He,

however, makes no

mention of Philæ or its temples. This omission on the part of one

who, wherever

he went, sought the society of the priests and paid particular

attention to the

religious observances of the country, shows that either Herodotus never

got so

far, or that the island had not yet become the home of the Osirian

mysteries.

Four hundred years later, Diodorus Siculus describes it as the holiest

of holy

places; while Strabo, writing about the same time, relates that Abydos

had then

dwindled to a mere village. It seems possible, therefore, that at some

period

subsequent to the time of Herodotus and prior to that of Diodorus or

Strabo,

the priests of Isis may have migrated from Abydos to Philæ; in

which case there

would have been a formal transfer not only of the relics of Osiris, but

of the

sanctity which had attached for ages to their original resting-place.

Nor is

the motive for such an exodus wanting. The ashes of the god were no

longer safe

at Abydos. Situate in the midst of a rich corn country on the high road

to

Thebes, no city south of Memphis lay more exposed to the hazards of

war.

Cambyses had already passed that way. Other invaders might follow. To

seek

beyond the frontier that security which might no longer be found in

Egypt,

would seem therefore to be the obvious course of a priestly guild

devoted to

its trust. This, of course, is mere conjecture, to be taken for what it

may be

worth. The decadence of Abydos coincides, at all events, with the

growth of Philæ;

and it is only by help of some such assumption that one can understand

how a

new site should have suddenly arisen to such a height of holiness. The

earliest temple here, of which only a small propylon remains, would

seem to

have been built by the last of the native Pharaohs (Nectanebo II, B.C.

361);

but the high and palmy days of Philæ belong to the period of

Greek and Roman

rule. It was in the time of the Ptolemies that the Holy Island became

the seat

of a sacred college and the stronghold of a powerful hierarchy.

Visitors from

all parts of Egypt, travellers from distant lands, court functionaries

from

Alexandria charged with royal gifts, came annually in crowds to offer

their

vows at the tomb of the god. They have cut their names by hundreds all

over the

principal temple, just like tourists of to-day. Some of these antique

autographs are written upon and across those of preceding visitors;

while

others – palimpsests upon stone, so to say – having been

scratched on the yet

unsculptured surface of doorway and pylon, are seen to be older than

the

hieroglyphic texts which were afterwards carved over them. These

inscriptions

cover a period of several centuries, during which time successive

Ptolemies and

Cæsars continued to endow the island. Rich in lands, in temples,

in the

localisation of a great national myth, the Sacred College was yet

strong enough

in A.D. 379 to oppose a practical resistance to the edict of

Theodosius. At a

word from Constantinople, the whole land of Egypt was forcibly

Christianised. Priests

were forbidden under pain of death to perform the sacred rites.

Hundreds of

temples were plundered. Forty thousand statues of divinities were

destroyed at

one fell swoop. Meanwhile, the brotherhood of Philæ, entrenched

behind the cataract and the desert, survived the degradation of their order and

the ruin

of their immemorial faith. It is not known with certainty for how long

they

continued to transmit their hereditary privileges; but two of the

above-mentioned votive inscriptions show that so late as A.D. 453 the

priestly

families were still in occupation of the island, and still celebrating

the

mysteries of Osiris and Isis. There even seems reason for believing

that the

ancient worship continued to hold its own till the end of the sixth

century, at

which time, according to an inscription at Kalabsheh, of which I shall

have

more to say hereafter, Silco, “King of all the Ethiopians,”

himself apparently

a Christian, twice invaded Lower Nubia, where God, he says gave him the

victory, and the vanquished swore to him “by their idols”

to observe the

terms of peace.4 There is

nothing in this record to show that the invaders went beyond Tafa, the

ancient

Taphis, which is twenty-seven miles above Philæ; but it seems

reasonable to

conclude that so long as the old gods yet reigned in any part of Nubia,

the

island sacred to Osiris would maintain its traditional sanctity. At length,

however, there must have come a day when for the last time the tomb of

the god

was crowned with flowers, and the “Lamentations of Isis”

were recited on the

threshold of the sanctuary. And there must have come another day when

the cross

was carried in triumph up those painted colonnades, and the first

Christian

mass was chanted in the precincts of the heathen. One would like to

know how these

changes were brought about; whether the old faith died out for want of

worshippers, or was expelled with clamour and violence. But upon this

point,

history is vague5 and the graffiti of the time are silent.

We only

know for certain that the old went out, and the new came in; and that

where the

resurrected Osiris was wont to be worshipped according to the most

sacred

mysteries of the Egyptian ritual, the resurrected Christ was now adored

after

the simple fashion of the primitive Coptic Church. And now

the Holy Island, near which it was believed no fish had power to swim

or bird

to fly, and upon whose soil no pilgrim might set foot without

permission,

became all at once the common property of a populous community. Courts,

colonnades, even terraced roofs, were overrun with little crude-brick

dwellings. A small basilica was built at the lower end of the island.

The

portico of the great temple was converted into a chapel, and dedicated

to Saint

Stephen. “This good work,” says a Greek inscription traced

there by some

monkish hand of the period, “was done by the well-beloved of God,

the

Abbot-Bishop Theodore.” Of this same Theodore, whom another

inscription styles

“the very holy father,” we know nothing but his name. The walls

hereabout are full of these fugitive records. “The cross has

conquered, and

will ever conquer,” writes one anonymous scribe. Others have left

simple

signatures; as, for instance – “I, Joseph,” in one

place, and “I, Theodosius of

Nubia,” in another. Here and there an added word or two give a

more human

interest to the autograph. So, in the pathetic scrawl of one who writes

himself

“Johannes, a slave,” we seem to read the story of a life in

a single line.

These Coptic signatures are all followed by the sign of the cross. The

foundations of the little basilica, with its apse towards the east and

its two

doorways to the west, are still traceable. We set a couple of our

sailors one

day to clear away the rubbish at the lower end of the nave, and found

the font

– a rough stone basin at the foot of a broken column. It is not

difficult to guess what Philæ must have been like in the days of

Abbot Theodore

and his flock. The little basilica, we may be sure, had a cluster of

mud domes

upon the roof; and I fancy, somehow, that the Abbot and his monks

installed

themselves in that row of cells on the east side of the great

colonnade, where

the priests of Isis dwelt before them. As for the village, it must have

been

just like Luxor – swarming with dusky life; noisy with the babble

of children,

the cackling of poultry, and the barking of dogs; sending up thin

pillars of

blue smoke at noon; echoing to the measured chime of the prayer-bell at

morn

and even; and sleeping at night as soundly as if no ghost-like,

mutilated gods

were looking on mournfully in the moonlight. The gods

are avenged now. The creed which dethroned them is dethroned. Abbot

Theodore

and his successors, and the religion they taught, and the simple folk

that

listened to their teaching, are gone and forgotten. For the church of

Christ,

which still languishes in Egypt, is extinct in Nubia. It lingered long;

though

doubtless in some such degraded and barbaric form as it wears in

Abyssinia to

this day. But it was absorbed by Islamism at last; and only a ruined

convent

perched here and there upon some solitary height, or a few crosses

rudely

carved on the walls of a Ptolemaic temple, remain to show that

Christianity

once passed that way. The

mediæval history of Philæ is almost a blank. The Arabs,

having invaded Egypt

towards the middle of the seventh century, were long in the land before

they

began to cultivate literature; and for more than three hundred years

history is

silent. It is not till the tenth century that we once again catch a

fleeting

glimpse of Philæ. The frontier is now removed to the head of the cataract. The

Holy Island has ceased to be Christian; ceased to be Nubian; contains a

mosque

and garrison, and is the last fortified outpost of the Moslems. It

still

retains, and apparently continues to retain for some centuries longer,

its ancient

Egyptian name. That is to say (P being as usual converted into B) the

Pilak of

the hieroglyphic inscriptions becomes in Arabic Belak; 6 which

is

much more like the original than the Philæ of the Greeks. The native

Christians, meanwhile, would seem to have relapsed into a state of

semi-barbarism. They make perpetual inroads upon the Arab frontier, and

suffer

perpetual defeat. Battles are fought; tribute is exacted; treaties are

made and

broken. Towards the close of the thirteenth century, their king being

slain and

their churches plundered, they lose one-fourth of their territory,

including

all that part which borders uppon Assûan. Those who remain

Christians are also

condemned to pay an annual capitation tax, in addition to the usual

tribute of

dates, cotton, slaves, and camels. After this we may conclude that they

accepted Islamism from the Arabs, as they had accepted Osiris from the

Egyptians and Christ from the Romans. As Christians, at all events, we

hear of

them no more; for Christianity in Nubia perished root and branch, and

not a

Copt, it is said, may now be found above the frontier. Philæ was

still inhabited in A.D. 1799, when a detachment of Desaix’s army

under General

Beliard took possession of the island, and left an inscription7 on

the soffit of the doorway of the great pylon to commemorate the passage

of the cataract. Denon, describing the scene with his usual vivacity, relates

how the

natives first defied and then fled from the French; flinging themselves

into

the river, drowning such of their children as were too young to swim,

and

escaping into the desert. They appear at this time to have been mere

savages –

the women ugly and sullen; the men naked, agile, quarrelsome, and armed

not

only with swords and spears, but with matchlock guns, which they used

to keep

up “a brisk and well-directed fire.” Their

abandonment of the island probably dates from this time; for when

Burckhardt

went up in A.D. 1813, he found it, as we found it to this day, deserted

and

solitary. One poor old man – if indeed he still lives – is

now the one

inhabitant of Philæ; and I suspect he only crosses over from

Biggeh in the

tourist-season. He calls himself, with or without authority, the

guardian of

the island; sleeps in a nest of rags and straw in a sheltered corner

behind the

great temple; and is so wonderfully wizened and bent and knotted up,

that

nothing of him seems quite alive except his eyes. We gave him fifty

copper

paras8 for a parting present when on our way back to Egypt;

and he

was so oppressed by the consciousness of wealth, that he immediately

buried his

treasure and implored us to tell no one what we had given him. With the

French siege and the flight of the native population closes the last

chapter of

the local history of Philæ. The Holy Island has done henceforth

with wars of

creeds or kings. It disappears from the domain of history, and enters

the

domain of science. To have contributed to the discovery of the

hieroglyphic

alphabet is a high distinction; and in no sketch of Philæ,

however slight, should

the obelisk9 that furnished Champollion with the name of

Cleopatra

be allowed to pass unnoticed. This monument, second only to the Rosetta

Stone

in point of philological interest, was carried off by Mr. W. Bankes,

the

discoverer of the first tablet of Abydos, and is now in Dorsetshire.

Its empty

socket and its fellow obelisk, mutilated and solitary, remain in

situ at

the southern extremity of the island. And now –

for we have lingered over long in the portico – it is time we

glanced at the

interior of the temple. So we go in at the central door, beyond which

open some

nine or ten halls and side-chambers leading, as usual, to the

sanctuary. Here

all is dark, earthy, oppressive. In rooms unlighted by the faintest

gleam from

without, we find smoke-blackened walls covered with elaborate

bas-reliefs.

Mysterious passages, pitch-dark, thread the thickness of the walls and

communicate by means of trap-like openings with vaults below. In the

sanctuary

lies an overthrown altar; while in the corner behind it stands the very

niche

in which Strabo must have seen that poor sacred hawk of Ethiopia which

he

describes as “sick, and nearly dead.” But in

this temple dedicated not only to Isis, but to the memory of Osiris and

the

worship of Horus their son, there is one chamber which we may be quite

sure was

shown neither to Strabo nor Diodorus, nor to any stranger of alien

faith, be

his repute or station what it might; a chamber holy above all others;

holier

even than the sanctuary; – the chamber sacred to Osiris. We,

however,

unrestricted, unforbidden, are free to go where we list; and our books

tell us

that this mysterious chamber is somewhere overhead. So, emerging once

again

into the daylight, we go up a well-worn staircase leading out upon the

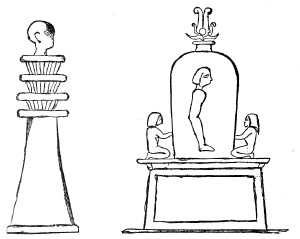

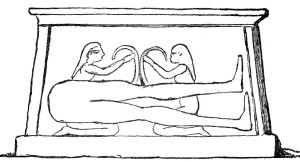

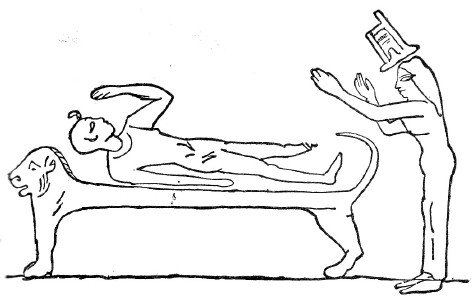

roof. This roof is an intricate, up-and-down place; and the room is not easy to find. It lies at the bottom of a little flight of steps – a small stone cell some twelve feet square, lighted only from the doorway. The walls are covered with sculptures representing the shrines, the mummification, and the resurrection of Osiris.10 These shrines, containing each some part of his body, are variously fashioned. His head, for instance, rests on a Nilometer; his arm, surmounted by a head, is sculptured on a stela, in shape resembling a high-shouldered bottle, surmounted by one of the head-dresses peculiar to the god; his legs and feet lie at full length in a pylon-shaped mausoleum. Upon another shrine stands the mitre-shaped crown which he wears as judge of the lower world. Isis and Nephthys keep guard over each shrine. In a lower frieze we see the mummy of the god laid upon a bier, with the four so-called canopic jars11 ranged underneath. A little farther on, he lies in state, surrounded by lotus buds on tall stems, figurative of growth, or returning life.12 Finally, he is depicted lying on a couch; his limbs reunited; his head, left hand, and left foot upraised, as in the act of returning to consciousness. Nephthys, in the guise of a winged genius, fans him with the breath of life. Isis, with outstretched arms, stands at his feet and seems to be calling him back to her embraces. The scene represents, in fact, that supreme moment when Isis pours forth her passionate invocations, and Osiris is resuscitated by virtue of the songs of the divine sisters.13

Ill-modelled

and ill-cut as they are, there is a clownish naturalness about these

little

sculptures which lifts them above the conventional dead level of

ordinary

Ptolemaic work. The figures tell their tale intelligibly. Osiris seems

really

struggling to rise, and the action of Isis expresses clearly enough the

intention of the artist. Although a few heads have been mutilated and

the

surface of the stone is somewhat degraded, the subjects are by no means

in a

bad state of preservation. In the accompanying sketches, nothing has

been done

to improve the defective drawing or repair the broken outlines of the

originals. Osiris in one has lost his foot, and in another his face;

the hands

of Isis are as shapeless as those of a bran doll; and the

naiveté of the

treatment verges throughout upon caricature. But the interest attaching

to them

is altogether apart from the way in which they are executed. And now,

returning to the roof, it is pleasant to breathe the fresher air that

comes

with sunset – to see the island, in shape like an ancient

Egyptian shield,

lying mapped out beneath one’s feet. From here, we look back upon

the way we

have come, and forward to the way we are going. Northward lies the cataract – a

network of islets with flashes of river between. Southward, the broad

current

comes on in one smooth, glassy sheet, unbroken by a single rapid. How

eagerly

we turn our eyes that way; for yonder lie Abou Simbel and all the

mysterious

lands beyond the cataracts! But we cannot see far, for the river curves

away

grandly to the right, and vanishes behind a range of granite hills. A

similar

chain hems in the opposite bank; while high above the palm-groves

fringing the

edge of the shore stand two ruined convents on two rocky prominences,

like a

couple of castles on the Rhine. On the east bank opposite, a few mud

houses and

a group of superb carob trees mark the site of a village, the greater

part of

which lies hidden among palms. Behind this village opens a vast sand

valley,

like an arm of the sea from which the waters have retreated. The old

channel

along which we rode the other day went ploughing that way straight

across from

Philæ. Last of all, forming the western side of this fourfold

view, we have the

island of Biggeh – rugged, mountainous, and divided from

Philæ by so narrow a

channel that every sound from the native village on the opposite steep

is as

audible as though it came from the courtyard at our feet. That village

is built

in and about the ruins of a tiny Ptolemaic temple, of which only a

screen and

doorway and part of a small propylon remain. We can see a woman

pounding coffee

on the threshold of one of the huts, and some children scrambling about

the

rocks in pursuit of a wandering turkey. Catching sight of us up here on

the

roof of the temple, they come whooping and scampering down to the

water-side,

and with shrill cries importune us for bakhshîsh. Unless the

stream is wider

than it looks, one might almost pitch a piastre into their outstretched

hands. Mr. Hay,

it is said, discovered a secret passage of solid masonry tunnelled

under the

river from island to island. The entrance on this side was from a shaft

in the temple of Isis.14 We are not told how far Mr. Hay was able

to

penetrate in the direction of Biggeh; but the passage would lead up,

most

probably, to the little temple opposite. Perhaps

the most entirely curious and unaccustomed features in all this scene

are the

mountains. They are like none that any of us have seen in our diverse

wanderings. Other mountains are homogeneous, and thrust themselves up

from

below in masses suggestive of primitive disruption and upheaval. These

seem to

lie upon the surface foundationless; rock loosely piled on rock,

boulder on

boulder; like stupendous cairns, the work of demigods and giants. Here

and there,

on shelf or summit, a huge rounded mass, many tons in weight, hangs

poised

capriciously. Most of these blocks, I am persuaded, would

“log,” if put to the

test. But for a

specimen stone, commend me to yonder amazing monolith down by the

water’s edge

opposite, near the carob trees and the ferry. Though but a single block

of

orange-red granite, it looks like three; and the Arabs, seeing in it

some

fancied resemblance to an arm-chair, call it Pharaoh’s throne.

Rounded and

polished by primæval floods, and emblazoned with royal cartouches

of

extraordinary size, it seems to have attracted the attention of

pilgrims of all

ages. Kings, conquerors, priests, travellers, have covered it with

records of

victories, of religious festivals, of prayers, and offerings, and acts

of

adoration. Some of these are older by a thousand years and more than

the

temples on the island opposite. Such,

roughly summed up, are the fourfold surroundings of Philæ –

the cataract, the

river, the desert, the environing mountains. The Holy Island –

beautiful,

lifeless, a thing of the far past, with all its wealth of sculpture,

painting,

history, poetry, tradition – sleeps, or seems to sleep, in the

midst. It is one of the world’s famous landscapes, and it deserves its fame. Every sketcher sketches it; every traveller describes it. Yet it is just one of those places of which the objective and subjective features are so equally balanced that it bears putting neither into words nor colours. The sketcher must perforce leave out the atmosphere of association which informs his subject; and the writer’s description is at best no better than a catalogue raisonnée. ___________________________ 1 Mariette,

at the end of his "Aperçu de l’histoire d’Egypte,"

gives the following

succinct account of the Rosetta Stone, and the discovery of

Champollion: “Découverte,

il y a 65 ans environ, par des soldats français qui creusaient

un retranchement

près d’une redoute située à Rosette, la

pierre qui porte ce nom a joué le plus

grand rôle dans l’archéologie égyptienne. Sur

la face principale sont gravées trois

inscriptions. Les deux premières sont en langue

égyptienne et écrites dans les

deux écritures qui avaient cours à cette époque.

L’une est en écriture

hiéroglyphique réservée aux prêtres; elle ne

compte plus que 14 lignes

tronquées par la brisure de la pierre. L’autre est en une

écriture cursive

appliquée principalement aux usages du peuple et comprise par

lui: celle-ci

offre 32 lignes de texte. Enfin, la troisième inscription de la

stèle est en

langue grecque et comprend 54 lignes. C’est dans cette

dernière partie que

réside l’intérêt du monument trouvé

à Rosette. Il résulte, en effet, de

l’interprétation du texte grec de la stèle que ce

texte n’est qu’une version de

l’original transcrit plus haut dans les deux écritures

égyptiennes. La Pierre

de Rosette nous donne donc, dans une langue parfaitement connue (le

grec) la

traduction d’un texte conçu dans une autre langue encore

ignorée au moment où

la stèle a été découverte. Qui ne voit

l’utilité de cette mention? Remonter du

connu à l’inconnu n’est pas une opération en

dehors des moyens d’une critique

prudente, et déjà l’on devine que si la Pierre de

Rosette a acquis dans la

science la célébrité dont elle jouit

aujourd’hui, c’est qu’elle a fourni la

vraie clef de cette mystérieuse écriture dont

l’Égypte a si longtemps gardé le

secret. Il ne faudrait pas croire cependant que le déchiffrement

des

hiéroglyphes au moyen de la Pierre de Rosette ait

été obtenu du premier coup et

sans tâtonnements. Bien au contraire, les savants s’y

essayérent sans succès

pendant 20 ans. Enfin, Champollion parut. Jusqu’à lui, on

avait cru que chacune

des lettres qui composent l’écriture hiéroglyphique

etait un symbole;

c’est à dire, que dans une seule de ces lettres

était exprimée une idée

complète. Le mérite de Champollion été de

prouver qu’au contraire l’écriture

égyptienne contient des signes qui expriment

véritablement des sons. En

d’autres termes qu’elle est Alphabétique. Il

remarqua, par exemple, que

partout où dans le texte grec de Rosette se trouve le nom propre

Ptolémée,

on rencontre à l’endroit correspondant du texte

égyptien un certain nombre de

signes enfermés dans un encadrement elliptique. Il en conclut:

1°, que les noms

des rois étaient dans le systéme hiéroglyphique

signalés à l’attention par une

sorte d’écusson qu’il appela cartouche:

2°, que les signes contenus dan

cet écusson devaient être lettre pour lettre le nom de

Ptolémée. Déjà donc en

supposant les voyelles omises, Champollion était en possession

de cinq lettres

– P, T, L, M, S. D’un autre côté, Champollion

savait, d’après une seconde

inscription grecque gravée sur une obélisque de

Philæ, que sur cet obélisque un

cartouche hiéroglyphique qu’on y voit devait être

celui de Cléopâtre. Si sa

première lecture était juste, le P, le L, et le T, de

Ptolémée devaient se

retrouver dans le second nom propre; mais en même temps ce second

nom propre

fournissait un K et un R nouveaux. Enfin, appliqué à

d’autres cartouches,

l’alphabet encore très imparfait

révélé à Champollion par les noms de

Cléopâtre

et de Ptolémée le mit en possession d’à peu

près toutes les autres consonnes.

Comme prononciation des signes, Champollion n’avait donc

pas à hésiter,

et dès le jour où cette constatation eut lieu, il put

certifier qu’il était en

possession de l’alphabet égyptien. Mais restait la langue;

car prononcer des

mots n’est rien si l’on ne sait pas ce que ces mots veulent

dire. Ici le génie

de Champollion se donna libre cours. Il s’aperçut en effet

que son alphabet

tiré des noms propres et appliqué aux mots de la langue

donnait tout simplement

du Copte. Or, le Copte à son tour est une langue qui,

sans être aussi

explorée que le grec, n’en était pas moins depuis

longtemps accessible. Cette

fois le voile était donc complétement levé. La

langue égyptienne n’est que du

Copte écrit en hiéroglyphes; ou, pour parler plus

exactement, le Copte n’est

que la langue des anciens Pharaons, écrite, comme nous

l’avons dit plus haut,

en lettres grecques. Le reste se devine. D’indices en indices,

Champollion

procéda véritablement du connu à l’inconnu,

et bientôt l’illustre fondateur de

l’égyptologie put poser les fondements de cette belle

science qui a pour objet

l’interprétation des hiéroglyphes. Tel est la

Pierre de Rosette.” – "Aperçu

de l’histoire d’Egypte:" Mariette Bey, p. 189 et

seq.: 1872. In order

to have done with this subject, it may be as well to mention that

another

trilingual tablet was found by Mariette while conducting his

excavations at Sân

(Tanis) in 1865. It dates from the ninth year of Ptolemy Euergetes, and

the

text ordains the deification of Berenice, a daughter of the king, then

just

dead (B.C. 254). This stone, preserved in the museum at Boulak, is

known as the

Stone of Sân, or the Decree of Canopus. Had the Rosetta Stone

never been

discovered, we may fairly conclude that the Canopic Decree would have

furnished

some later Champollion with the necessary key to hieroglyphic

literature, and

that the great discovery would only have been deferred till the present

time. NOTE TO

SECOND EDITION. – A third copy of the Decree of Canopus, the text

engraved in

hieroglyphs only, was found at Tell Nebireh in 1885, and conveyed to

the Boulak

Museum. The discoverer of this tablet, however, missed a much greater

discovery, reserved, as it happened, for Mr. W. M. F. Petrie, who came

to the

spot a month or two later, and found that the mounds of Tell Nebireh

entombed

the remains of the famous and long-lost Greek city of Naukratis. See "Naukratis,"

Part I, by W. M. F. Petrie, published by the Egypt Exploration Fund,

1886. 2 The famous

capitals are not the only specimens of admirable colouring in

Philæ. Among the

battered bas-reliefs of the great colonnade at the south end of the

island,

there yet remain some isolated patches of uninjured and very lovely

ornament.

See, more particularly, the mosaic pattern upon the throne of a

divinity just

over the second doorway in the western wall; and the designs upon a

series of

other thrones a little farther along towards the north, all most

delicately

drawn in uniform compartments, picked out in the three primary colours,

and

laid on in flat tints of wonderful purity and delicacy. Among these a

lotus

between two buds, an exquisite little sphinx on a pale red ground, and

a series

of sacred hawks, white upon red, alternating with white upon blue, all

most

exquisitely conventionalised, may be cited as examples of absolutely

perfect

treatment and design in polychrome decoration. A more instructive and

delightful task than the copying of these precious fragments can hardly

be

commended to students and sketchers on the Nile. 3 It has

since been pointed out by a writer in The Saturday Review that

this

credence-table was fashioned with part of a shrine destined for one of

the

captive hawks sacred to Horus. [Note to second edition.] 4 In the

time of Strabo, the island of Philæ, as has been recently shown

by Professor

Revillout in his "Seconde Mémoire sur les Blemmys," was

the common

property of the Egyptians and Nubians, or rather of that obscure nation

called

the Blemmys, who, with the Nobades and Megabares, were collectively

classed at

that time as “Ethiopians.” The Blemmys (ancestors of the

present Barabras) were

a stalwart and valiant race, powerful enough to treat on equal terms

with the

Roman rulers of Egypt. They were devout adorers of Isis, and it is

interesting

to learn that in the treaty of Maximin with this nation, it is

expressly

provided that, “according to the old law,” the Blemmys were

entitled to take

the statue of Isis every year from the sanctuary of Philæ to

their own country

for a visit of a stated period. A graffito at Philæ, published by

Letronne,

states that the writer was at Philæ when the image of the goddess

was brought

back from one of these periodical excursions, and that he beheld the

arrival of

the sacred boats “containing the shrines of the divine

statues.” From this it

would appear that other images than that of Isis had been taken to

Ethiopia;

probably those of Osiris and Horus, and possibly also that of Hathor,

the

divine nurse. [Note to second edition.] 5 The

Emperor Justinian is credited with the mutilation of the sculptures of

the

large Temple; but the ancient worship was probably only temporarily

suspended

in his time. 6 These and

the following particulars about the Christians of Nubia are found in

the famous

work of Makrizi, an Arab historian of the fifteenth century, who quotes

largely

from earlier writers. See Burckhardt’s Travels in Nubia,

4to, 1819,

Appendix iii. Although Belak is distinctly described as an island in

the

neighbourhood of the Cataract, distant four miles from Assûan,

Burckhardt

persisted in looking for it among the islets below Mahatta, and

believed Philæ

to be the first Nubian town beyond the frontier. The hieroglyphic

alphabet,

however, had not then been deciphered. Burckhardt died at Cairo in

1817, and

Champollion’s discovery was not given to the world till 1822. 7 This

inscription, which M. About considers the most interesting thing in

Philæ, runs

as follows: “L’An VI de la République, le 15

Messidor, une Armée Française

commandée par Bonaparte est descendue a Alexandrie.

L’Armée ayant mis, vingt

jours après, les Mamelouks en fuite aux Pyramides, Desaix,

commandant la

première division, les a poursuivis au dela des Cataractes, ou

il est arrivé le

18 Ventôse de l’an VII.” 8 About

two-and-sixpence English. 9 See

previous note, p. 181. 10 The story

of Osiris – the beneficent god, the friend of man, slain and

dismembered by

Typhon; buried in a score of graves; sought by Isis; recovered limb by

limb;

resuscitated in the flesh; transferred from earth to reign over the

dead in the

world of Shades – is one of the most complex of Egyptian legends.

Osiris under

some aspects is the Nile. He personifies Abstract Good, and is entitled

Unnefer, or “The Good Being.” He appears as a Myth of the

Solar Year. He bears

a notable likeness to Prometheus, and to the Indian Bacchus. “Osiris,

dit-on, était autrefois descendu sur la terre. Être bon

par excellence, il

avait adouci les mœurs des hommes par la persuasion et la

bienfaisance. Mais il

avait succombé sous les embûches de Typhon, son

frère, le génie du mal, et

pendant que ses deux sœurs, Isis et Nephthys, recueillaient son

corps qui avait

été jeté dans le fleuve, le dieu ressuscitait

d’entre les morts et apparaissait

à son fils Horus, qu’il instituait son vengeur.

C’est ce sacrifice qu’il avait

autrefois accompli en faveur des hommes qu’Osiris renouvelle ici

en faveur de

l’âme dégagée de ses liens terrestres. Non

seulement il devient son guide, mais

il s’identifie à elle; il l’absorbe en son propre

sein. C’est lui alors qui,

devenu le défunt lui-même, se soumet à toutes les

épreuves que celui-ci doit

subir avant d’être proclamé juste; c’est lui

qui, à chaque âme qu’il doit

sauver, fléchit les gardiens des demeures infernales et combat

les monstres

compagnons de la nuit et de la mort; c’est lui enfin qui,

vainqueur des

ténèbres, avec l’assistance d’Horus,

s’assied au tribunal de la suprême justice

et ouvre à l’âme déclarée pure les

portes du séjour éternel. L’image de la mort

aura été empruntée au soleil qui disparâit

à l’horizon du soir: le soleil

resplendissant du matin sera la symbole de cette seconde naissance

à une vie

qui, cette fois, ne connaîtra pas la mort. “Osiris

est donc le principe du bien. . . . Chargé de sauver les

âmes de la mort

définitive, il est l’intermédiaire entre

l’homme et Dieu; il est le type et le

sauveur de l’homme.” "Notice des Monuments à

Boulaq" – Aug. Mariette Bey,

1872, pp. 105 et seq. [It has

always been taken for granted by Egyptologists that Osiris was

originally a

local god of Abydos, and that Abydos was the cradle of the Osirian

Myth.

Professor Maspero, however, in some of his recent lectures at the

Collége de

France, has shown that the Osirian cult took its rise in the Delta;

and, in

point of fact, Osiris, in certain ancient inscriptions, is styled the

King Osiris

“Lord of Tattu” (Busiris), and has his name enclosed in a

royal oval. Up to the

time of the Græco-Roman rule, the only two cities of Egypt in

which Osiris

reigned as the principal god were Busiris and Mendes.] “Le centre

terrestre du culte d’Osiris, était dans les cantons

nord-est du Delta, situés

entre la branche Sébennytique et la branche Pélusiaque,

comme le centre

terrestre du culte de Sit, le frère et le meurtrier

d’Osiris; les deux dieux

étaient limitrophes l’un de l’autre, et des

rivalités de voisinage expliquent

peut-être en partie leurs querelles. . . . Tous le traits de la

tradition

Osirienne ne sont pas également anciens: le fond me parait

être d’une antiquité

incontestable. Osiris y réunit les caractères des deux

divinités qui se partageaient

chaque nome: il est le dieu des vivants et le dieu des morts en

même temps; le

dieu qui nourrit et le dieu qui détruit. Probablement, les temps

où, saisi de

pitié pour les mortels, il leur ouvrit l’accès de

son royaume, avaient été

précédés d’autres temps où il

était impitoyable et ne songeait qu’à les

anéantir. Je crois trouver un souvenir de ce rôle

destructeur d’Osiris dans

plusieurs passages des textes des Pyramides, où l’on

promet au mort que

Harkhouti viendra vers lui, ‘déliant ses liens, brisant

ses chaines pour le

délivrer de la ruine; il ne le livrera pas à Osiris,

si bien qu’il ne mourra

pas, mais il sera glorieux dans l’horizon, solide comme le

Did dans la

ville de Didou.’ L’Osiris farouche et cruel fut

absorbé promptement par

l’Osiris doux et bienveillant. L’Osiris qui domine toute la

religion égyptienne

dès le début, c’est l’Osiris Onnofris,

l’Osiris Être bon, que les Grecs ont

connu. Commes ses parents, Sibou et Nouit, Osiris Onnofris appartient

à la

classe des dieux généraux qui ne sont pas confinés

en un seul canton, mais qui

sont adorés par un pays entier.” See "Les

Hypogées Royaux de Thèbes"

(Bulletin critique de la religion égyptienne) par Professeur G.

Maspero – "Revue

de l’histoire des Réligions," 1888. [Note to second edition.] “The astronomical

and physical elements are too obvious to be mistaken. Osiris and Isis

are the

Nile and Egypt. The myth of Osiris typifies the solar year – the

power of

Osiris is the sun in the lower hemisphere, the winter solstice. The

birth of

Horus typifies the vernal equinox – the victory of Horus, the

summer solstice –

the inundation of the Nile. Typhon is the automnal equinox.” "Egypt’s

Place

in Universal History" – Bunsen, 1st ed. vol. i. p. 437. “The

Egyptians do not all worship the same gods, excepting Isis and

Osiris.” –

Herodotus, book ii. 11 “These

vases, made of alabaster, calcareous stone, porcelain, terra-cotta, and

even

wood, were destined to hold the soft parts or viscera of the body,

embalmed

separately and deposited in them. They were four in number, and were

made in

the shape of the four genii of the Karneter, or Hades, to whom were

assigned

the four cardinal points of the compass.” Birch’s "Guide

to the First and

Second Egyptian Rooms," 1874, p. 89. See also Birch’s "History

of Ancient

Pottery," 1873, p. 23 et seq. 12 Thus

depicted, he is called “the germinating Osiris.” [Note to second edition.] 13 See M. P.

J. de Horrack’s translation of "The Lamentations of Isis and

Nephthys."

Records of the Past, vol. ii. p. 117 et seq. 14 "Operations

carried on at the Pyramids of Ghizeh" – Col. Howard

Vyse, London, 1840,

vol. i. p. 63. |