| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER XX. SILSILIS AND EDFU. GOING, it

cost us four days to struggle up from Assûan to Mahatta;

returning, we slid down – thanks to our old friend the sheik of

the cataract –

in one short, sensational half hour. He came – flat-faced,

fishy-eyed, fatuous

as ever – with his head tied up in the same old yellow

handkerchief, and with

the same chibouque in his mouth. He brought with him a following of

fifty

stalwart Shellalees; and under his arm he carried a tattered red flag.

This

flag, on which were embroidered the crescent and star, he hoisted with

much

solemnity at the prow. Consigned

thus to the protection of the Prophet; windows and tambooshy1

shuttered; doors closed; breakables removed to a place of

safety, and everything

made snug, as if for a storm at sea, we put off from Mahatta at seven

A.M. on a

lovely morning in the middle of March. The Philæ, instead of

threading her way

back through the old channels, strikes across to the Libyan side,

making

straight for the Big Bab – that formidable rapid which as yet we

have not seen.

All last night we heard its voice in the distance; now, at every stroke

of the

oars, that rushing sound draws nearer. The sheik of the cataract is our captain, and his men are our sailors

to-day; Reïs Hassan and the crew having only to sit still and look

on. The

Shellalees, meanwhile, row swiftly and steadily. Already the river

seems to be

running faster than usual; already the current feels stronger under our

keel.

And now, suddenly, there is sparkle and foam on the surface yonder

– there are

rocks ahead; rocks to right and left; eddies everywhere. The sheik

lays down

his pipe, kicks off his shoes, and goes himself to the prow. His second

in

command is stationed at the top of the stairs leading to the upper

deck. Six

men take the tiller. The rowers are reinforced, and sit two to each

side. In the

midst of these preparations, when everybody looks grave, and even

the Arabs are silent, we all at once find ourselves at the mouth of a

long and

narrow strait – a kind of ravine between two walls of rock

– through which, at

a steep incline, there rushes a roaring mass of waters. The whole Nile,

in

fact, seems to be thundering in wild waves down that terrible channel. It seems,

at first sight, impossible that any dahabeeyah should venture

that way and not be dashed to pieces. The sheik, however, gives the

word – his

second echoes it – the men at the helm obey. They put the

dahabeeyah straight

at that monster mill-race. For one breathless second we seem to tremble

on the

edge of the fall. Then the Philæ plunges in headlong! We see the

whole boat slope down bodily under our feet. We feel the leap

– the dead fall – the staggering rush forward. Instantly

the waves are foaming

and boiling up on deck with spray. The men ship their oars, leaving all

to helm

and current; and, despite the hoarse tumult, we distinctly hear those

oars

scrape the rocks on either side. Now the sheik, looking for the moment quite majestic, stands motionless

with uplifted arm; for at the end of this pass there is a sharp turn to

the

right – as sharp as a street corner in a narrow London

thoroughfare. Can the

Philæ, measuring 100 feet from stem to stern, ever round that

angle in safety?

Suddenly the uplifted arm is waved – the sheik thunders

“Daffet!” (helm) – the

men, steady and prompt, put the helm about – the boat, answering

splendidly to

the word of command, begins to turn before we are out of the rocks;

then,

shooting round the corner at exactly the right moment, comes out safe

and

sound, with only an oar broken! Great is

the rejoicing. Reïs Hassan, in the joy of his heart, runs to

shake hands all round; the Arabs burst into a chorus of

“Taibs” and “Salames;”

and Talhamy, coming up all smiles, is set upon by half-a-dozen playful

Shellalees, who snatch his keffîyeh from his head, and carry it

off as a

trophy. The only one unmoved is the sheik of the cataract. His

momentary flash

of energy over, he slouches back with the old stolid face; slips on his

shoes;

drops on his heels; lights his pipe; and looks more like an owl than

ever. We had

fancied till now that the cataract Arabs for their own profit,

and travellers for their own glory, had grossly exaggerated the dangers

of the

Big Bab. But such is not the case. The Big Bab is in truth a serious

undertaking; so serious that I doubt whether any English boatmen would

venture

to take such a boat down such a rapid, and between such rocks, as the

Shellalee

Arabs took the Philæ that day. All

dahabeeyahs, however, are not so lucky. Of thirty-four that shot the

fall this season, several had been slightly damaged, and one was so

disabled

that she had to lie up at Assûan for a fortnight to be mended. Of

actual

shipwreck, or injury to life and limb, I do not suppose there is any

real danger.

The Shellalees are wonderfully cool and skilful, and have abundant

practice.

Our painter, it is true, preferred rolling up his canvases and carrying

them

round on dry land by way of the desert; but this was a precaution that

neither

he nor any of us would have dreamed of taking on account of our own

personal

safety. There is, in fact, little, if anything, to fear; and the

traveller who

forgoes the descent of the cataract, forgoes a very curious sight, and

a very

exciting adventure. At

Assûan we bade farewell to Nubia and the blameless Ethiopians,

and

found ourselves once more traversing the Nile of Egypt. If instead of

five

miles of Cataract we had crossed five hundred miles of sea or desert,

the

change could not have been more complete. We left behind us a dreamy

river, a

silent shore, an ever-present desert. Returning, we plunged back at

once into

the midst of a fertile and populous region. All day long, now, we see

boats on

the river; villages on the banks; birds on the wing; husbandmen on the

land; men

and women, horses, camels and asses, passing perpetually to and fro on

the

towing-path. There is always someting moving, something doing. The Nile

is

running low, and the shâdûfs – three deep, now

– are in full swing from morning

till night. Again the smoke goes up from clusters of unseen huts at

close of

day. Again we hear the dogs barking from hamlet to hamlet in the still

hours of

the night. Again, towards sunset, we see troops of girls coming down to

the

river-side with their water-jars on their heads. Those Arab maidens,

when they

stand with garments tightly tucked up and just their feet in the water,

dipping

the goollah at arm’s length in the fresher gush of the current,

almost tempt

one’s pencil into the forbidden paths of caricature. Kom Ombo

is a magnificent torso. It was as large once as Denderah –

perhaps larger; for, being on the same grand scale, it was a double

Temple and

dedicated to two gods, Horus and Sebek;2 the Hawk and the

Crocodile.

Now there remain only a few giant columns buried to within eight or ten

feet of

their gorgeous capitals; a superb fragment of architrave; one broken

wave of

sculptured cornice, and some fallen blocks graven with the names of

Ptolemies

and Cleopatras. A great

double doorway, a hall of columns, and a double sanctuary, are

said to be yet perfect, though no longer accessible. The roofing blocks

of

three halls, one behind the other, and a few capitals, are yet visible

behind

the portico. What more may lie buried below the surface, none can tell.

We only

know that an ancient city and a mediæval hamlet have been slowly

engulfed; and

that an early Temple, contemporary with the Temple of Amada, once stood

within

the sacred enclosure. The sand here has been accumulating for 2000

years. It

lies forty feet deep, and has never been excavated. It will never be

excavated

now; for the Nile is gradually sapping the bank, and carrying away

piecemeal

from below what the desert has buried from above. Half of one noble

pylon – a

cataract of sculptured blocks – strews the steep slope from top

to bottom. The

other half hangs suspended on the brink of the precipice. It cannot

hang so

much longer. A day must soon come when it will collapse with a crash,

and

thunder down like its fellow. Between

Kom Ombo and Silsilis, we lost our Painter. Not that he either

strayed or was stolen; but that, having accomplished the main object of

his

journey, he was glad to seize the first opportunity of getting back

quickly to

Cairo. That opportunity – represented by a noble Duke

honeymooning with a steam-tug

– happened half-way between Kom Ombo and Silsilis. Painter and

Duke being

acquaintances of old, the matter was soon settled. In less than a

quarter of an

hour, the big picture and all the paraphernalia of the studio were

transported

from the stern-cabin of the Philæ to the stern-cabin of the

steam-tug; and our painter – fitted out with an extempore canteen, a cook-boy, a

waiter, and his

fair share of the necessaries of life – was soon disappearing

gaily in the

distance at the rate of twenty miles an hour. If the happy couple, so

weary of

head-winds, so satiated with Temples, followed that vanishing steam-tug

with

eyes of melancholy longing, the writer at least asked nothing better

than to

drift on with the Philæ. Still, the

Nile is long, and life is short; and the tale told by our

logbook was certainly not encouraging. When we reached Silsilis on the

morning

of the 17th of March, the north wind had been blowing with only one

day’s

intermission since the 1st of February. At

Silsilis, one looks in vain for traces of that great barrier which

once blocked the Nile at this point. The stream is narrow here, and the

sandstone cliffs come down on both sides to the water’s edge. In

some places

there is space for a footpath; in others, none. There are also some

sunken

rocks in the bed of the river – upon one of which, by the way, a

Cook’s steamer

had struck two days before. But of such a mass as could have dammed the

Nile,

and by its disruption not only have caused the river to desert its bed

at

Philæ,3 but have changed the whole physical and

climatic conditions

of Lower Nubia, there is no sign whatever. The Arabs

here show a rock fantastically quarried in the shape of a

gigantic umbrella, to which they pretend some king of old attached one

end of a

chain with which he barred the Nile. It may be that in this apocryphal

legend

there survives some memory of the ancient barrier. The cliffs

of the western bank are rich in memorial niches, votive

shrines, tombs, historical stelæ, and inscriptions. These last

date from the

seventh to the twenty-second dynasties. Some of the tombs and alcoves are very

curious.

Ranged side by side in a long row close above the river, and revealing

glimpses

of seated figures and gaudy decorations within, they look like private

boxes

with their occupants. In most of these we found mutilated triads of gods,4

sculptured and painted; and in one larger than the rest

were three

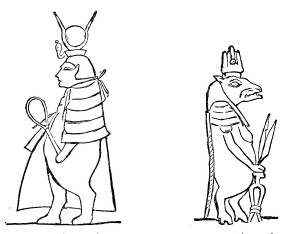

niches, each containing three deities. The great speos of Horemheb, the last Pharaoh of the eigfhteenth dynasty, lies farthest north, and the memorial shrines of the Rameses family lie farthest south of the series. The first is a long gallery, like a cloister supported on four square columns; and is excavated parallel with the river. The walls inside and out are covered with delicately executed sculptures in low relief, some of which yet retain traces of colour. The triumph of Horemheb returning from conquest in the land of Kush, and the famous subject on the south wall described by Mariette5 as one of the few really lovely things in Egyptian art, have been too often engraved to need description. The votive shrines of the Rameses family are grouped all together in a picturesque nook green with bushes to the water’s edge. There are three, the work of Seti I, Rameses II, and Menepthah – lofty alcoves, each like a little proscenium, with painted cornices and side pillars, and groups of kings and gods still bright with colour. In most of the votive sculptures of Silsilis there figure two deities but rarely seen elsewhere; namely Sebek, the Crocodile god, and Hapi-mu, the lotus-crowned god of the Nile. This last was the tutelary deity of the spot, and was worshipped at Silsilis with special rites. Hymns in his honour are found carved here and there upon the rocks.6 Most curious of all, however, is a goddess named Ta-ur-t,7 represented in one of the side subjects of the shrine of Rameses II. This charming person, who has the body of a hippopotamus and the face of a woman, wears a tie-wig and a robe of state with five capes, and looks like a cross between a lord chancellor and a coachman. Behind her stand Thoth and Nut; all three receiving the homage of Queen Nefertari, who advances with an offering of two sistrums. As a hippopotamus crowned with the disk and plumes, we had met with this goddess before. She is not uncommon as an amulet; and the writer had already sketched her at Philæ, where she occupies a prominent place in the façade of the Mammisi. But the grotesque elegance of her attire at Silsilis, is, I imagine, quite unique.

The

interest of the western bank centres in its sculptures and

inscriptions; the interest of the eastern bank, in its quarries. We

rowed over

to a point nearly opposite the shrines of the Ramessides, and, climbing

a steep

verge of débris, came to the mouth of a narrow cutting between

walls of solid

rock, from forty to fifty feet in height. These walls are smooth,

clean-cut,

and faultlessly perpendicular. The colour of the sandstone is rich

amber. The

passage is about ten feet in width and perhaps four hundred in length.

Seen at

a little after mid-day, with one side in shadow, the other in sunlight,

and a

narrow ribbon of blue sky overhead, it is like nothing else in the

world;

unless, perhaps, the entrance to Petra. Following

this passage, we came presently to an immense area, at least

as large as Belgrave Square; beyond which, separated by a thin

partition of

rock, opened a second and somewhat smaller area. On the walls of these

huge

amphitheatres, the chisel-marks and wedge-holes were as fresh as if the

last

blocks had been taken hence but yesterday; yet it is some 2000 years

since the

place last rang to the blows of the mallet, and echoed back the voices

of the

workmen. From the days of the Theban Pharaohs to the days of the

Ptolemies and

Cæsars, those echoes can never have been silent. The temples of

Karnak and

Luxor, of Gournah, of Medinet Habu, of Esneh and Edfu and Hermonthis,

all came

from here, and from the quarries on the opposite side of the river.8

Returning,

we climbed long hills of chips; looked down into valleys of

débris; and came back at last to the river-side by way of an

ancient inclined

plane, along which the blocks were slid down to the transport boats

below. But

the most wonderful thing about Silsilis is the way in which the

quarrying has

been done. In all these halls and passages and amphitheatres, the

sandstone has

been sliced out smooth and straight, like hay from a hayrick.

Everywhere the

blocks have been taken out square; and everywhere the best of the stone

has

been extracted, and the worst left. When it was fine in grain and even

in

colour, it has been cut with the nicest economy. Where it was whitish,

or

brownish, or traversed by veins of violet, it has been left standing.

Here and

there, we saw places where the lower part had been removed and the

upper part

left projecting, like the overhanging storeys of our old mediæval

timber

houses. Compared with this puissant and perfect quarrying, our

rough-and-ready

blasting looks like the work of savages. Struggling

hard against the wind, we left Silsilis that same afternoon.

The wrecked steamer was now more than half under water. She had broken

her back

and begun filling immediately, with all Cook’s party on board.

Being rowed

ashore with what necessaries they could gather together, these

unfortunates had

been obliged to encamp in tents borrowed from the mudîr of the

district.

Luckily for them, a couple of homeward-bound dahabeeyahs came by next

morning,

and took off as many as they could accommodate. The Duke’s

steam-tug received

the rest. The tents were still there, and a gang of natives, under the

superintendence of the mudîr, were busy getting off all that

could be saved

from the wreck. As evening

drew on, our head-wind became a hurricane; and that hurricane

lasted, day and night, for thirty-six hours. All this time the Nile was

driving

up against the current in great rollers, like rollers on the Cornish

coast when

tide and wind set together from the west. To hear them roaring past in

the

darkness of the night – to feel the Philæ rocking,

shivering, straining at her

mooring-ropes, and bumping perpetually against the bank, was far from

pleasant.

By day, the scene was extraordinary. There were no clouds; but the air

was

thick with sand, through which the sun glimmered feebly. Some palms,

looking

grey and ghost-like on the bank above, bent as if they must break

before the

blast. The Nile was yeasty, and flecked with brown foam, large lumps of

which

came swirling every now and then against our cabin windows. The

opposite bank

was simply nowhere. Judging only by what was visible from the deck, one

would

have vowed that the dahabeeyah was moored against an open coast, with

an angry

sea coming in. The wind

fell about five A.M. the second day; when the men at once took

to their oars, and by breakfast-time brought us to Edfu. Nothing now

could be

more delicious than the weather. It was a cool, silvery, misty morning

– such a

morning as one never knows in Nubia, where the sun is no sooner up than

one is

plunged at once into the full blaze and stress of day. There were

donkeys

waiting for us on the bank, and our way lay for about a mile through

barley

flats and cotton plantations. The country looked rich; the people

smiling and

well-conditioned. We met a troop of them going down to the dahabeeyah

with

sheep, pigeons, poultry, and a young ox for sale. Crossing a back-water

bridged

by a few rickety palm-trunks, we now approached the village, which is

perched,

as usual, on the mounds of the ancient city. Meanwhile the great pylons

–

seeming to grow larger every moment – rose, creamy in light,

against a soft

blue sky. Riding

through lanes of huts, we came presently to an open space and a

long flight of roughly built steps in front of the temple. At the top

of these

steps we were standing on the level of the modern village. At the

bottom we saw

the massive pavement that marked the level of the ancient city. From

that level

rose the pylons which even from afar off had looked so large. We now

found that

those stupendous towers not only soared to a height of about

seventy-five feet

above our heads, but plunged down to a depth of at least forty more

beneath our

feet. Ten years

ago, nothing was visible of the great temple of Edfu save the

tops of these pylons. The rest of the building was as much lost to

sight as if

the earth had opened and swallowed it. Its courtyards were choked with

foul

débris. Its sculptured chambers were buried under forty feet of

soil. Its

terraced roof was a maze of closely packed huts, swarming with human

beings,

poultry, dogs, kine, asses, and vermin. Thanks to the indefatigable

energy of

Mariette, these Augæan stables were cleansed some thirty years

ago. Writing

himself of this trememdous task, he says: “I caused to be

demolished the

sixty-four houses which encumbered the roof, as well as twenty-eight

more which

approached too near the outer wall of the temple. When the whole shall

be

isolated from its present surroundings by a massive wall, the work of

restoration at Edfu will be accomplished.”9 That wall

has not yet been built; but the encroaching mound has been cut

clean away all round the building, now standing free in a deep open

space, the

sides of which are in some places as perpendicular as the quarried

cliffs of

Silsilis. In the midst of this pit, like a risen god issuing from the

grave,

the huge building stands before us in the sunshine, erect and perfect.

The

effect at first sight is overwhelming. Through

the great doorway, fifty feet in height, we catch glimpses of a

grand courtyard, and of a vista of doorways, one behind another. Going

slowly

down, we see farther into those dark and distant halls at every step.

At the

same time the pylons, covered with gigantic sculptures, tower higher

and

higher, and seem to shut out the sky. The custode – a pigmy of

six foot two, in

semi-European dress – looks up grinning, expectant of

bakhshîsh. For there is

actually a custode here, and, which is more to the purpose, a good

strong gate,

through which neither pilfering visitors nor pilfering Arabs can pass

unnoticed. Who enters

that gate crosses the threshold of the past, and leaves two

thousand years behind him. In these vast courts and storied halls all

is

unchanged. Every pavement, every column, every stair, is in its place.

The

roof, but for a few roofing-stones missing just over the sanctuary, is

not only

uninjured, but in good repair. The hieroglyphic inscriptions are as

sharp and

legible as the day they were cut. If here and there a capital, or the

face of a

human-headed deity, has been mutilated, these are blemishes which at

first one

scarcely observes, and which in no wise mar the wonderful effect of the

whole.

We cross that great courtyard in the full blaze of the morning

sunlight. In the

colonnades on either side there is shade, and in the pillared portico

beyond, a

darkness as of night; save where a patch of deep blue sky burns through

a

square opening in the roof, and is matched by a corresponding patch of

blinding

light on the pavement below. Hence we pass on through a hall of

columns, two

transverse corridors, a side chapel, a series of pitch-dark side

chambers, and

a sanctuary. Outside all these, surrounding the actual Temple on three

sides,

runs an external corridor open to the sky, and bounded by a superb wall

full

forty feet in height. When I have said that the entrance-front, with

its twin pylons

and central doorway, measures 250 feet in width by 125 feet in height;

that the

first courtyard measures more than 160 feet in length by 140 in width;

that the

entire length of the building is 450 feet, and that it covers an area

of 80,000

square feet, I have stated facts of a kind which convey no more than a

general

idea of largeness to the ordinary reader. Of the harmony of the

proportions, of

the amazing size and strength of the individual parts, of the perfect

workmanship, of the fine grain and creamy amber of the stone, no

description

can do more than suggest an indefinite notion. Edfu and

Denderah may almost be called twin Temples. They belong to the

same period. They are built very nearly after the same plan.10 They

are even allied in a religious sense; for the myths of Horus11 and

Hathor12 are interdependent; the one being the complement

of the

other. Thus in the inscriptions of Edfu we find perpetual allusion to

the

cultus of Denderah, and vice versa. Both Edfu and Denderah are rich in

inscriptions;

but as the extent of wall-space is greater at Edfu, so is the literary

wealth

of this Temple greater than the literary wealth of Denderah. It also

seemed to

me that the surface was more closely filled in at Edfu than at

Denderah. Every

wall, every ceiling, every pillar, every architrave, every passage and

side-chamber however dark, every staircase, every doorway, the outer

wall of

the Temple, the inner side of the great wall of circuit, the huge

pylons from

top to bottom, are not only covered, but crowded, with figures and

hieroglyphs.

Among these we find no enormous battle-subjects as at Abou Simbel

– no heroic

recitals, like the poem of Pentaur. Those went out with the Pharaohs,

and were

succeeded by tableaux of religious rites and dialogues of gods and

kings. Such

are the stock subjects of Ptolemaic edifices. They abound at Denderah

and

Esneh, as well as at Edfu. But at Edfu there are more inscriptions of a

miscellaneous character than in any Temple of Egypt; and it is

precisely this

secular information which is so priceless. Here are geographical lists

of

Nubian and Egyptian nomes, with their principal cities, their products,

and

their tutelary gods; lists of tributary provinces and princes; lists of

temples, and of the lands pertaining thereunto; lists of canals, of

ports, of

lakes; kalendars of feasts and fasts; astronomical tables; genealogies

and

chronicles of the gods; lists of the priests and priestesses of both

Edfu and

Denderah, with their names; lists also of singers and assistant

functionaries;

lists of offerings, hymns, invocations; and such a profusion of

religious

legends as make the walls of Edfu alone a complete text-book of

Egyptian

mythology.13 No great

collection of these inscriptions, like the “Denderah” of

Mariette, has yet been published; but every now and then some

enterprising

Egyptologist such as M. Naville or M. Jacques de Rougé, plunges

for a while

into the depths of the Edfu mine and brings back as much precious ore

as he can

carry. Some most singular and interesting details have thus been

brought to

light. One inscription, for instance, records exactly in what month,

and on

what day and at what hour, Isis gave birth to Horus. Another tells all

about

the sacred boats. We know now that Edfu possessed at least two; and

that one was

called Hor-Hāt, or The First Horus, and the other Āa-Māfek, or Great of

Turquoise. These boats, it would appear, were not merely for carrying

in

procession, but for actual use upon the water. Another text – one

of the most

curious – informs us that Hathor of Denderah paid an annual visit

to Horus (or

Hor-Hāt) of Edfu, and spent some days with him in his Temple. The whole

ceremonial of this fantastic trip is given in detail. The goddess

travelled in

her boat called Neb-Mer-t, or Lady of the Lake. Horus, like a polite

host, went

out in his boat Hor-Hāt, to meet her. The two deities with their

attendants

then formed one procession, and so came to Edfu, where the goddess was

entertained with a successions of festivals.14 One would

like to know whether Horus duly returned all these visits; and

if the gods, like modern Emperors, had a gay time among themselves. Other

questions inevitably suggest themselves, sometimes painfully,

sometimes ludicrously, as one paces chamber after chamber, corridor

after

corridor, sculptured all over with strange forms and stranger legends.

What

about these gods whose genealogies are so intricate; whose mutual

relations are

so complicated; who wedded and became parents; who exchanged visits,

and who

even travelled15 at times to distant countries? What about

those who

served them in the Temples; who robed and unrobed them; who celebrated

their

birthdays, and paraded them in stately processions, and consumed the

lives of

millions in erecting these mountains of masonry and sculpture to their

honour?

We know now with what elaborate rites the gods were adored; what jewels

they

wore; what hymns were sung in their praise. We know from what a subtle

and

philosophical core of solar myths their curious personal adventures

were

evolved. We may also be quite sure that the hidden meaning of these

legends was

almost wholly lost sight of in the later days of the religion,16 and

that the gods were accepted for what they seemed to be, and not for

what they

symbolised. What, then, of their worshippers? Did they really believe

all these

things, or were any among them tormented with doubts of the gods? Were

there

sceptics in those days, who wondered how two hierogrammates could look

each

other in the face without laughing? The

custode told us that there were 242 steps to the top of each tower

of the propylon. We counted 224, and dispensed willingly with the

remainder. It

was a long pull; but had the steps been four times as many, the sight

from the

top would have been worth the climb. The chambers in the pylons are on

a grand

scale, with wide bevelled windows like the mouths of monster

letter-boxes,

placed at regular intervals all the way up. Through these windows the

great

flagstaffs and pennons were regulated from within. The two pylons

communicate

by a terrace over the central doorway. The parapet of this terrace and

the

parapets of the pylons above, are plentifully scrawled with names, many

of

which were left there by the French soldiers of 1799. The

cornices of these two magnificent towers are unfortunately gone; but

the total height without them is 125 feet. From the top, as from the

minaret of

the great mosque at Damascus, one looks down into the heart of the

town.

Hundreds of mud-huts thatched with palm-leaves, hundreds of little

courtyards,

lie mapped out beneath one’s feet; and as the Fellâh lives

in his yard by day,

using his hut merely as a sleeping place at night, one looks down, like

the

Diable Boiteux, upon the domestic doings of a roofless world. We see

people

moving to and fro, unconscious of strange eyes watching them from above

– men

lounging, smoking, sleeping in shady corners – children playing

– infants

crawling on all fours – women cooking at clay ovens in the open

air – cows and

sheep feeding – poultry scratching and pecking – dogs

basking in the sun. The

huts look more like the lairs of prairie-dogs than the dwellings of

human

beings. The little mosque with its one dome and stunted minaret, so

small, so

far below, looks like a clay toy. Beyond the village, which reaches far

and

wide, lie barley fields, and cotton patches, and palm-groves, bounded

on one

side by the river, and on the other by the desert. A broad road, dotted

over

with moving specks of men and cattle, cleaves its way straight through

the

cultivated land and out across the sandy plain beyond. We can trace its

course

for miles where it is only a trodden track in the desert. It goes, they

tell

us, direct to Cairo. On the opposite bank glares a hideous white

sugar-factory,

and, bowered in greenery, a country villa of the Khedive. The broad

Nile flows

between. The sweet Theban hills gleam through a pearly haze on the

horizon. All at

once, a fitful breeze springs up, blowing in little gusts and

swirling the dust in circles round our feet. At the same moment, like a

beautiful spectre, there rises from the desert close by an undulating

semi-transparent stalk of yellow sand, which grows higher every moment,

and

begins moving northward across the plain. Almost at the same instant,

another

appears a long way off towards the south, and a third comes gliding

mysteriously along the opposite bank. While we are watching the third,

the

first begins throwing off a wonderful kind of plume, which follows it,

waving

and melting in the air. And now the stranger from the south comes up at

a smooth,

tremendous pace, towering at least 500 feet above the desert, till,

meeting

some cross-current, it is snapped suddenly in twain. The lower half

instantly

collapses; the upper, after hanging suspended for a moment, spreads and

floats

slowly, like a cloud. In the meanwhile, other and smaller columns form

here and

there – stalk a little way – waver – disperse –

form again – and again drop

away in dust. Then the breeze falls, and puts an abrupt end to this

extraordinary spectacle. In less than two minutes there is not a

sand-column

left. As they came, they vanish – suddenly. Such is

the landscape that frames the temple; and the temple, after all,

is the sight that one comes up here to see. There it lies far below our

feet,

the courtyard with its almost perfect pavement; the flat roof compact

of

gigantic monoliths; the wall of circuit with its panoramic sculptures;

the

portico, with its screen and pillars distinct in brilliant light

against inner

depths of dark; each pillar a shaft of ivory, each square of dark a

block of

ebony. So perfect, so solid so splendid is the whole structure; so

simple in

unity of plan; so complex in ornament; so majestic in completeness,

that one

feels as if it solved the whole problem of religious architecture. Take it

for what it is – a Ptolemaic structure preserved in all its

integrity of strength and finish – it is certainly the finest

extant temple in

Egypt. It brings before us, with even more completeness than Denderah,

the

purposes of its various parts, and the kind of ceremonial for which it

was

designed. Every corridor and chamber tells its own story. Even the

names of the

different chambers are graven upon them in such wise than nothing17

would

be easier than to reconstruct the ground-plan of the whole building in

hieroglyphic nomenclature. That neither the Ptolemaic building nor the

Ptolemaic mythus can be accepted as strictly representative of either

pure

Egyptian art or pure Egyptian thought, must of course be conceded. Both

are

modified by Greek influences, and have so far departed from the

Pharaonic

model. But then we have no equally perfect specimen of the Pharaonic

model. The

Ramesseum is but a grand fragment. Karnak and Medinet Habu are

aggregates of

many temples and many styles. Abydos is still half-buried. Amid so much

that is

fragmentary, amid so much that is ruined, the one absolutely perfect

structure

– Ptolemaic though it be – is of incalculable interest, and

equally

incalculable value. While we

are dreaming over these things, trying to fancy how it all

looked when the sacred flotilla came sweeping up the river yonder and

the

procession of Hor-Hāt issued forth to meet the goddess-guest –

while we are

half-expecting to see the whole brilliant concourse pour out, priests

in their

robes of panther-skin, priestesses with the tinkling sistrum, singers

and

harpists, and bearers of gifts and emblems, and high functionaries

rearing

aloft the sacred boat of the god – in this moment a turbaned

Muëddin comes out

upon the rickety wooden gallery of the little minaret below, and

intones the

call to mid-day prayer. That plaintive cry has hardly died away before

we see

men here and there among the huts turning towards the east, and

assuming the

first postures of devotion. The women go on cooking and nursing their

babies. I

have seen Moslem women at prayer in the mosques of Constantinople, but

never in

Egypt. Meanwhile,

some children catch sight of us, and, notwithstanding that we

are one hundred and twenty-five feet above their heads, burst into a

frantic

chorus of “Bakhshîsh!” And now, with a last long look at the temple and the wide landscape beyond, we come down again, and go to see a dismal little Mammesi three-parts buried among a wilderness of mounds close by. These mounds, which consist almost entirely of crude-brick débris with imbedded fragments of stone and pottery, are built up like coral-reefs, and represent the dwellings of some sixty generations. When they are cut straight through, as here round about the great temple, the substance of them looks like rich plum-cake. ______________________________1 Ar. Tambooshy – i.e. saloon skylight. 2 “Sebek est

un dieu solaire. Dans un papyrus de Boulak, il est appelé fils

d’Isis, et il

combat les ennemis d’Osiris; c’est une assimilation

complète à Horus, et c’est

à ce titre qu’il était adoré à

Ombos.” – "Dic.

Arch." P. Pierret. Paris, 1875. 3 See chap.

xi. p. 184. 4 “Le point

de départ de la mythologie egyptienne est une Triade.”

Champollion, Lettres

d’Egypte,

etc., XI Lettre. Paris, 1868. These Triads are best studied at Gerf

Hossayn

and Kalabsheh. 5 “L’un (paroi

du sud) représente une déesse nourissant de son lait

divin le roi Horus, encore

enfant. L’Egypte n’a jamais, comme la Grèce, atteint

l’idéal du beau . . . mais

en tant qu’art Egyptien, le bas-relief du Spéos de

Gebel-Silsileh est une des

plus belles œuvres que l’on puisse voir. Nulle part, en

effet, la ligne n’est

plus pure, et il règne dans ce tableau une certaine douceur

tranquille qui

charme et étonne à la fois.” – "Itinéraire de

la Haut Egypte." A. Mariette: 1872, p. 246. 6 See "Sallier Papyrus No. 2." Hymn To

The Nile –

translation by C. Maspero. 4to Paris, 1868. 7 Ta-ur-t, or Apet the Great. “Cettes

Déesse à corps

d’hippopotame debout et à mamelles pendantes, paraît

être une sorte de déesse

nourrice. Elle semble, dans le bas temps, je ne dirai pas se substituer

à Maut,

mais compléter le rôle de cette déesse. Elle est

nommée la grande nourrice; et

présidait aux chambres où étaient

représentées les naissances des jeunes

divinités.” – "Dict.

Arch." P.

Pierret. Paris, 1875. “In

the heavens, this goddess personified the constellation Ursa Major,

or the Great Bear.” – "Guide

to the First and

Second Egyptian Rooms. S. Birch. London, 1874. 8 For a

highly interesting account of the rock-cut inscriptions, graffiti, and

quarry-marks at Silsilis, in the desert between Assûan and

Philæ, and in the

valley called Soba Rigolah, see Mr. W. M. F. Petrie’s recent

volume entitled "A Season’s

Work in Egypt," 1877. 9 Letter of

M. Mariette to Vte E. de Rougé: "Révue

Archéologique," vol. ii. p. 33, 1860. 10 Edfu is

the older temple; Denderah the copy. Where the architect of Denderah

has

departed from his model, it has invariably been for the worse. 11 Horus:

– “Dieu

adoré dans plusieurs nomes de la basse Egypte. Le personnage

d’Horus se

rattache sous des noms différents, à deux generations

divines. Sous le nom de

Haroëris il est né de Seb et Nout, et par consequent

frère d’Osiris, dont il

est le fils sous un autre nom. . . . Horus, armé d’un dard

avec lequel il

transperce les ennemis d’Osiris, est appelé Horus le

Justicier.” – "Dict.

Arch." P. Pierret, article “Horus.” 12 Hathor:

– “Elle est,

comme Neith, Muat, et Nout, la personnification de l’espace dans

lequel se meut

le soleil, dont Horus symbolise le lever; aussi son nom, Hat-hor,

signifie-t-il

litteralement, l’habitation

d’Horus.”

– "Ibid." article “Hathor.” 13 "Rapport

sur une Mission en Egypte." Vicomte E. de

Rougé. See "Révue

Arch.

Nouvelle Série," vol. x. p. 63. 14 "Textes

Géographiques du Temple d’Edfou," by M. J. de

Rougé. "Révue Arch."

vol. xii. p. 209. 15 See

Professor Revillout’s "Seconde

Mémoire sure

les Blemmyes," 1888, for an account of how the statues of

Isis and

other deities were taken once a year from the Temples of Philæ

for a trip into

Ethiopia. 16 See

APPENDIX III, "Religious Belief of

the

Ancient Egyptians." 17 Not only

the names of the chambers, but their dimensions in cubits and

subdivisions of

cubits are given. See "Itinéraire

de la Haute

Egypte." A. Mariette Bey. 1872, p. 241. |