| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

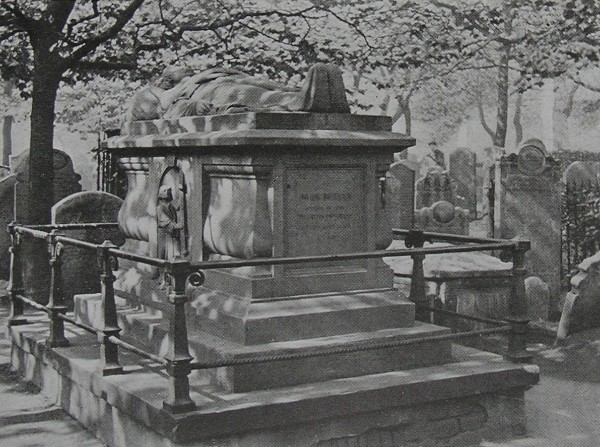

VIII

BUNHILL FIELDS BY common consent the two books which, next to the Bible, have been most widely read by English-speaking people are "The Pilgrim's Progress" and "Robinson Crusoe." Of the first Coleridge declared that he knew no book he could so safely recommend" as teaching and enforcing the whole saving truth; "Swift found in one of its chapters better entertainment and information than in long discourses on the will and intellect; Southey eulogized it as "a clear stream of current English;" Lord Karnes found its style akin to that of Homer with its "proper mixture of the dramatic and narrative;" and Macaulay concluded his judgment of its author with this oft-cited tribute: "We are not afraid to say that, though there were many clever men in England during the latter half of the seventeenth century, there were only two great creative minds. One of these minds produced the 'Paradise Lost,' the other 'The Pilgrim's Progress.' " Nor has "Robinson Crusoe" failed to win equal praise. Dr. Johnson placed it first among the three books he wished longer; Rousseau hailed it as the most complete "treatise on natural education;" Lamb declared it "delightful to all ranks and classes," equally at home in the kitchen and the libraries of the wealthiest and the most learned; Leslie Stephen credited its author with the gift of a tongue "to which no one could listen without believing every word that he uttered;" and Sir Walter Scott sums up the judgment of all by declaring that "there exists no book, either of instruction or entertainment, in the English language, which has been more generally read, and more universally admired." Yet the authors of these books, — books which have coloured the religious and imaginative thought of so many millions, — John Bunyan and Daniel Defoe, have no memorial of any kind in Westminster Abbey. Of course their creed, alien as it was from that of the Church of England, rendered their burial in the Abbey impossible in the late seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries. Nor, at that date, had England realized the abiding fame of the two writers. But it is different now. In this more charitable age the custodians of England's Valhalla do not enquire so closely into the religious faith of the nation's immortals, and that these two are secure of their place among those immortals no one doubts. Yet no memorial bust or votive tablet of either John Bunyan or Daniel Defoe has been set up in Westminster Abbey. Elsewhere, then, and not in the "long-drawn aisle" or beneath the fretted vault of stately Abbey or Cathedral, must the resting-place of these deathless writers be sought. Perhaps Bunyan and Defoe would have been well content that it should be so. Their nonconforming fellow-sleepers and stirring environment in Bunhill Fields are more in harmony with the lives they lived and the books they wrote than the austerity and aloofness of Westminster Abbey. Than those two places of sepulture it would be difficult to imagine burial-places of greater contrast. The atmosphere of the Abbey, for all the humanizing influence of Poets' Corner, is redolent of courtliness, and power, and high achievement in senate and battlefield, and the overmastering presence of royalty; and over all there broods that sense of repose and detachment from actual life which belongs to an outworn conception of religion. No such feelings oppress the visitor to Bunhill Fields. This ancient burial-ground, aptly described by Southey as "the Campo Santo of the Dissenters," is situated on the west side of City Road, one of the busiest of London's ever-crowded thoroughfares. From the dawning light of the longest summer day, and on through all its hours until dawn is about to break again, this highway is astir with human life. Close by are the headquarters of the Honourable Artillery Company; directly opposite is John Wesley's Chapel; right and left are several of London's most notable hospitals; and mingling indiscriminately with these reminders of war, and faith, and charity are countless warehouses, factories and other hives of industry. But as amidst the eddies of a whirlpool there are here and there placid surfaces in strange contrast to the seething waters around, so this historic God's acre offers the wayfarer a peaceful oasis in the restless tide of London life. In its quiet aloofness from human activity it perpetuates the rural repose which rested over Finsbury as a whole when the first grave was dug in Bunhill Fields. Two years after this plot of land had been definitely enclosed as a place of burial, Pepys found this neighbourhood distinguished for its "very pleasant" fields, and so it remained until well on into the eighteenth century. Every yard of those "very pleasant" fields has long since been given its burden of house, or church, or factory, or hospital, but the few acres of Bunhill Fields, because they were set apart for death's harvest, hold the devouring tide of bricks and mortar steadfastly at bay. Some two and a half centuries have passed since Bunhill Fields was devoted to the burial of the dead. One account antedates that event by more than another century, for it is affirmed that in 1549 more than a thousand cartloads of human remains were removed from the charnel of St. Paul's Cathedral and buried here. Perhaps that may account for the name of the cemetery, which is given as "Bonhill Field," that is "Bone-hill," in 1567. Whatever truth there may be in that philological guess, it is indubitable that ninety-eight years later, that is, in 1665, this portion of the manor of Finsbury was set apart by the authorities of the city of London, and enclosed by a brick wall, to provide a burial-place for the victims of the Great Plague. Happily, however, that dread scourge appears to have spent its force before the final arrangements for interments here had been made, and later the land was purchased by a Mr. Tindal who "converted it into a burial-ground for the use of Dissenters." It consequently became known as "Tindal's Burial-ground," a name which, although in use as late as 1756, has been entirely superseded by the older designation of Bunhill Fields. For nearly two centuries, that is, from 1665 to 1852, this plot of ground was industriously tilled by the spade of the grave-digger. A record of the interments shows that one hundred and twenty-three thousand mortals have been buried here, the great majority of whom were debarred by their non-conformist faith from sepulture in consecrated ground. "Nor," as it has been appositely remarked, "is theirs all ignoble dust. Some were buried here whose names have always been fondly cherished by the nation, and whose writings are amongst the most popular in the English language. Notable men of all professions and of all religious communities, divines, authors, and artists, with a crowd of worthies and confessors, whose learning and piety not only adorned the age in which they lived, but have proved a blessing to the land, are interred in this ground. Many thousands of persons not in England alone but in America and the British Colonies have honoured ancestors lying here." Four acres of land have a limit in their capacity for receiving human bodies, and that limit was reached at Bunhill Fields thirteen years before it attained the second century of its existence as a burial-ground. In 1852, then, the Secretary of State issued an order prohibiting further interments, and the Nonconformists of England, to whom this plot of ground had become endeared as the Westminster Abbey of their illustrious dead, had to seek a place of sepulture elsewhere. Then followed a period of comparative neglect for Bunhill Fields. For fifteen years the burial-ground, no longer brought freshly to mind by constant use, was abandoned. The rains levelled the mounds of earth, frost and wind worked their will on the monuments, and tangled grass and weeds completed the work of desolation. At this juncture the cemetery was threatened with complete extinction, for a rapacious ecclesiastical corporation, cloaking its desire for gold under legal technicalities, made an effort to secure possession of the ground with an eye to its exploitation for building purposes. Awakened in that way to the danger which imperilled a spot so sacred in their annals, the Nonconformists of England bestirred themselves, with the result that an act of Parliament was passed securing the inviolability of Bunhill Fields for ever. One result of that tardy recognition of the historic interest of this burial-ground may be seen in the orderly appearance it presents to-day. Extensive alterations and reparations were carried out as soon as the decision of Parliament was taken, but in the course of that work not a fragment of stone was taken away, nor any portion of the soil removed. Tombs have been raised from beneath the ground, stones have been set straight, illegible inscriptions have been deciphered and re-cut, hundreds of decayed tombs have been restored, paths have been laid and avenues planted; but in doing all this the sacred rights of sepulture have been scrupulously respected. Naturally, many of the original monuments are no longer in existence, but in the work of restoration it was found possible to ensure the preservation of some five thousand tombstones. Although the elements have obliterated so many thousands of the inscriptions graven on the memorials of Bunhill Fields, copies of the most important still exist. The accident of a venerable lady keeping a diary has preserved the memory of the man to whom we are indebted for those copies. The aged lady in question, who lived close by, "walked for the air" nowhere so frequently as in the "Dissenters' Burial Ground." Two children were her most constant companions, of whom the diarist records that they were at great pains to plant flowers over some neglected graves, and to copy down "most of the singular lines inscribed on the tombs." But a more industrious "Old Mortality" than those eager children was quietly at work in the same place. The diarist tells how one afternoon, after a visit to a nearby chapel, she and her pastor, Mr. Winter, and a clerical friend of the latter, Mat. Wilks, paid a visit to Bunhill Fields to see Dr. Owens' grave. "There," the diary says, "we found a worthy man known to Mr. Wilks, Mr. Rippon by name, who was laid down upon his side between two graves, and writing out the epitaphs word for word. He had an ink-horn in his button-hole, and a pen and book. He tells us that he has taken most of the old inscriptions, and that he will, if God be pleased to spare his days, do all, notwithstanding it is a grievous labour, and the writing is hard to make out by reason of the oldness of the cutting in some, and de-facings of other stones. It is a labour of love to him, and when he is gathered to his fathers, I hope some one will go on with his work." That pious wish was fulfilled. When Dr. Rippon laid aside his inkhorn and pen, the work upon which he had expended so much willing labour was taken up by other hands, and in the College of Heralds and the office of the Architect of the City of London are preserved complete records of all inscriptions existing in 1868. DANIEL DEFOE'S GRAVE Such matters, however, are mainly of appeal to the patient genealogist, the unwearied explorer of the intricacies of family history; for the majority who seek out Bunhill Fields the main interest lies in the fact that here it is possible to stand close beside the dust of Bunyan, Defoe, Isaac Watts, William Blake, and other sons of fame. Accident was responsible for Bunyan's burial in London. His own choice without doubt would have fallen on Bedford or the adjacent hamlet of Elstow. In the latter he was born and had spent his careless boyhood and early manhood; the former had been the scene of his weary imprisonment, the sphere of his labours as an author and preacher. When he became famous, alike for his prowess with his pen and his gifts as a speaker, he had many offers of preferment to larger and more lucrative positions, but nothing could induce him to leave Bedford, where he was supremely happy in his family and all other relationships. And there, unquestionably, he would have been laid to rest save for accident. Death was appointed to overtake him away from home. Starting out from Bedford to London, where his presence was needed in connection with a new book, he made a wide detour to Reading on a mission of reconciliation. A father he knew had quarrelled with his son, and threatened to disinherit him. Bunyan, however, was able to reunite the two, and, the mission accomplished, he then resumed his journey to the metropolis. But the delay caused him to be caught in a furious summer storm, through which he rode for forty miles. The evil effects of his drenching did not manifest themselves for a few days. In fact, he was able to preach on the Sunday after his arrival, but on the Tuesday following he was seized with a violent fever, and ten days later he breathed his last, his final utterance being, "Take me, for I come to Thee." And then his friends recalled that in his last sermon he had said: "Dost thou see a soul that has the image of God in him? Love him, love him: say, This man and I must go to heaven one day; serve one another, do good for one another; and if any wrong you, pray to God to right you, and love the brotherhood." That exhortation to broad charity was characteristic of the man. The author of "The Pilgrim's Progress" was an utter stranger to that narrowness which is sometimes thought to be inseparable from the faith he professed. "He was extremely tolerant in his terms of Church membership," says Froude. "He offended the stricter part of his congregation by refusing ever to make infant baptism a condition of exclusion. The only persons with whom he declined to communicate were those whose lives were openly immoral." He was no self-seeker. When a London merchant offered to take his son into his house, Bunyan replied, "God did not send me to advance my family, but to preach the Gospel." None need be surprised, then, that a man so transparently sincere, so human, so loving, so self-denying was heard gladly on the rare occasions when he preached in London; nor that many pleaded that they might in death be laid near his grave. It was no unusual event for more than a thousand people to assemble by seven o'clock on a dark winter's morning to hear him preach; ample indeed must the recompense have been to gaze upon his open ruddy face and sparkling eyes. Many of the better-off dissenters of London must have contended for the honour of acting host to the lovable Bedford preacher. On his last visit that privilege fell to the lot of one John Strudwick, a grocer in whose house ready hospitality had been given him often before. Mr. Strudwick possessed a vault in Bunhill Fields, where he had the mournful satisfaction of laying the dust of the immortal dreamer. The monument, which was restored by public subscription in 1862, sustains a recumbent figure of the Bedford preacher and bears the simple inscription: "John Bunyan, Author of 'The Pilgrim's Progress,' ob. 31st August, 1688, aet. 60." Forty-three years were to elapse ere the author of "Robinson Crusoe" came to join the author of "The Pilgrim's Progress" in the silent companionship of Bunhill Fields. Unlike in their lives and characters, Bunyan and Defoe had nothing in common in death. Pitiful, indeed, is the contrast between the final earthly hours of these two. Such fame and prosperity as Defoe won by "Robinson Crusoe" came to him late in life, for he was nearly sixty when he penned that classic; but for all that the closing year or two of his existence held nothing of the comfort of wealth or the happiness of renown. Over the multifarious activities of Defoe a sudden eclipse descended in September, 1729. He had a new book partly in type when he ceased his labours abruptly and fled to some mysterious hiding-place. Why is unknown. Among the many reasons advanced the most credible is that which does Defoe the least honour. Any way, it is a sad picture we have of an old man, weary with much labour, cut off from his familiar haunts and his family, a homeless, desolate, penurious wanderer. He died on April 26th, 1731, in Ropemaker's Alley, Moorfields, and it was no doubt the proximity of his deathplace to Bunhill Fields which led to his burial there. The recorder of the interment made the bare and ignorant entry, "1731, April 26. Mr. Dubow, Cripplegate;" and the creator of Robinson Crusoe had to wait a hundred and forty years before his resting-place was marked by any monument. How that long over-due tribute was paid to Defoe, the following inscription explains: "This monument is the result of an appeal in 'The Christian World ' newspaper to the boys and girls of England for funds to place a suitable memorial upon the grave of Daniel Defoe. It represents the united contributions of seventeen hundred persons. Sept. 1870." THE CROMWELL VAULT  JOHN BUNYAN'S TOMB Among the other notable sleepers in this God's Acre are Dr. Thomas Goodwin, who watched by the death-bed of Oliver Cromwell; General Charles Fleetwood, a prominent leader in the Civil War and the son-in-law of the Protector; Susannah Wesley, the mother of John and Charles Wesley; Joseph Ritson, the laborious antiquary; Isaac Watts, the famous hymnologist; Nathaniel Mather, "the honour of both Englands;" and William Blake, the mystic painter-poet whose genius has given employment to many pens during the past few years. THE GRAVE OF ISAAC WATTS Although it was in a humble room that Blake died,—the one modest apartment in which he spent his days and nights with his beloved wife, painting, drawing, studying, cooking and sleeping within its walls, — his death-bed was radiant with happiness. Almost the last stroke of his pencil was employed in a hasty sketch of his wife, "ever an angel" to him, and his expiring breath was spent in songs, words and melody being the offspring of the moment. "My beloved," he said to his wife of these songs, "they are not mine — no — they are not mine.' He died on August 12th, 1827, and at his own request he was buried in Bunhill Fields, where his parents and others of his relatives had been laid. No monument at present marks the resting-place of Blake. He was placed in a "common grave," which was doubtless used for other interments. Its position, however, is definitely known, and it may be that ere many years have passed some simple memorial will be raised over the dust of one to whom "the veil of outer things seemed always to tremble with some breath behind it." |