| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

IX

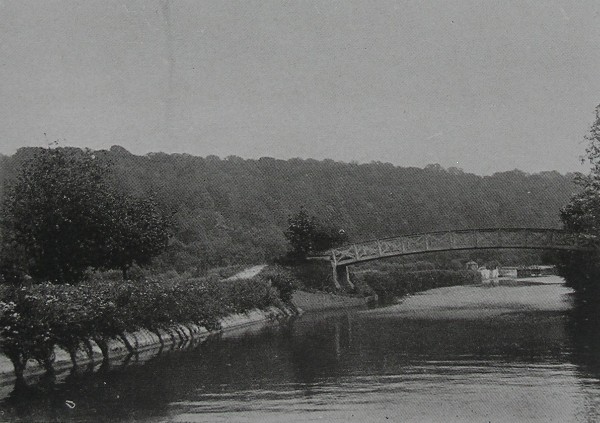

FRED WALKER'S COOKHAM GRANTING to a given poet and a given painter the possession of equal genius, the latter will always have to wait longer than the former for widespread recognition of his merits. The reason seems capable of a simple explanation. By paper and print the poet can multiply his verses indefinitely, and the millionth printed copy is as efficacious in advertising his genius as the first. But the case of the painter is not so fortunate. His fame in the last resort must rest upon the actual sight of his pictures, and that experience can be enjoyed by comparatively few. In his lifetime most of his paintings are acquired by private owners, and thus withdrawn from public gaze; their brief exhibition in art galleries only provides opportunity for the minority to make their acquaintance. Happily, however, that minority includes the critics of art, to whom falls the responsibility of advising the world when a new genius makes his appearance. But their influence is slow in reaching the great public, even though it may be reinforced by reproductions of a selected picture here and there. Still, the eulogy of the critic is responsible in the end for the artist's ultimate fame. Pictures which are praised by many pens awaken the desire of wealthy connoisseurs, and when that stage is reached the popular verdict is won. Perhaps it hardly accords with the dignity of art that its general recognition should owe so much to the cheque-book of its rich patron; but the fact remains and must be accepted with the best grace possible. Max Nordau cynically notes that on the day when six hundred thousand francs were paid for Millet's "Angelus" the "snobs of both worlds took off their hats and murmured in a voice hushed with reverence: 'This must be a great painter.' As we see, the world's fame is but a question of money. Many more men are able to reckon than are able to feel the beauty of art, and, to the vast majority, its price is the infallible, the one key to the understanding of a work." During the present year the cheque-book stamp of merit has been placed on the art of Frederick Walker. At an important picture sale, where canvases by Millais, and Mason, and David Cox and Turner were offered for the eager competition of wealthy collectors, Walker's water colour replica of "The Harbour of Refuge" aroused spirited bidding and finally realized two thousand five hundred and eighty guineas, the highest price of the day. FRED WALKER'S HOME AT COOKHAM One inevitable result will follow in the wake of this monetary triumph: Cookham, that lovely Thames-side village which inspired so much of Walker's best work, will in the future prove as attractive for its artistic associations as it has been in the past for its aquatic pleasures. Nay, more. It is not improbable that the humble cottage in which Walker lived, and the modest headstone which marks his grave, will acquire a greater interest for future visitors than the "stately houses of titled and wealthy Englishmen" which had so overpowering an effect on a pilgrim of a year or two ago. This obsessed note-taker does not appear to have heard of the name of Frederick Walker; but he waxes eloquent about my Lord This who owns such and such a seat, his Grace That whose mansion stands just here, and about a notorious expatriated American who possesses the most gorgeous estate of them all. Well, who shall grudge them their brief fame? Lord will follow lord, and duke succeed duke, and millionaire shall come after millionaire, but for the ages unborn the greatest glory of Cookham will be that its quaint street and verdant meadows and bosky trees and peaceful river are transferred for ever to the poetic landscapes of Frederick Walker. In the apportionment of years only three and a half decades were allotted to the artist, and of these some twenty-five had fled before he learnt to know and love this picturesque corner of Berkshire. But those twenty-five years had prepared him to reap the rich harvest awaiting his brush here. Frederick Walker was born in London in 1840, of parents who on his father's side could claim artistic ancestry, and on his mother's a descent from forebears who had an intuitive love of the beautiful. After brief and haphazard schooling he, while in his teens, began to frequent the Elgin Marble room of the British Museum, and, by assiduous drawing from the antique, acquired that sense of classic form which was to prove so invaluable in after years. Apprenticeship to wood engraving followed, and when he had not completed his twentieth year he had entered upon his artistic career by making wood-cuts for the, press. This soon led to an introduction to Thackeray, who at the time was on the look-out for an artist to illustrate "The Adventures of Philip." The meeting between the two is described by George Smith, who drove the young man to the novelist's house. "When we went up to Mr. Thackeray, he saw how nervous and distressed the young artist was. After a little time he said, 'Can you draw? Mr. Smith says you can.' 'Y-e-e-s, I think so,' said the young man who was, within a few years, to excite the admiration of the whole world by the excellence of his drawings. 'I'm going to shave,' said Mr. Thackeray, 'would you mind drawing my back?' Mr. Thackeray went to his toilet table and commenced the operation, while Mr. Walker took a sheet of paper and began his drawing; I looking out of the window in order that he might not feel that he was being watched. I think Mr. Thackeray's idea of turning his back towards him was as ingenious as it was kind; for I believe that if Mr. Walker had been asked to draw his face instead of his back, he would hardly have been able to hold his pencil." This was in 1860, and the acquaintance thus begun soon ripened into friendship, which knew no break until the great-hearted novelist passed suddenly away three years later. Thackeray's daughter tells how Walker came running to the house when he heard of her father's death, and of how he was met "wandering about the stairs in tears." To follow the further stages in his career as he finally left periodical illustrating behind and came before the world as an artist in his own right is not necessary. Suffice it to say that by 1865, when he had reached his twenty-fifth year, he had already won enviable repute for his artistic skill. At this crisis some happy chance led to his taking a cottage at Cookham, as a summer home for himself and his devoted mother and sister and brother. That modest dwelling stands in the main street of the village, about midway between the railway station and the Thames. Perhaps it is hardly the kind of dwelling an artist would have been expected to choose, for its flint-built walls and ungainly height are far from picturesque. Hither, however, for the remaining ten years of his life, Walker frequently came, thus building up for this homely cottage a wealth of association which many a more stately home must envy. COOKHAM LOCK  COOKHAM, ON THE THAMES But if his cottage home at Cookham was not beautiful, the village itself, and other near-by hamlets, and the surrounding fields, and the "silver-streaming" Thames were replete with incipient pictures. The painter's mother realized that fact. "This is a very lovely place," she wrote soon after reaching the village. "Fred would be delighted; and for a summer picture of boys bathing, there cannot be its equal, at least in my experience." Such was to be the experience of her son too. Whether he was indebted to his mother for the suggestion is not on record, but there is plentiful evidence to show that it was at Cookham the idea for "The Bathers" first took possession of Walker's mind, and that it was by the banks of the Thames he worked at and finally achieved that masterly canvas. As he entered on his task he told his sister that "beginning a picture is like taking a wife; one must cleave to it, leaving one's relations and everything, to work when one can." It proved a more formidable undertaking than he had imagined, but he devoted to its completion every day that could be spared from other work, and his letters are full of proofs of the exacting labour entailed by the production of a great picture. He searched far and wide for just that nature setting which would satisfy his ideal, and at last he was rewarded. One day, he writes, he "came to a place having for a background that which will top everything for the picture, instead of Cliveden, though I shall keep the nearer trees, also the meadows and rushes, just the same. I got so excited that I saw the whole thing done from beginning to end. . . . When I saw the loveliness to-day, the whole picture came before me in such a way, that I decided upon commencing on the big canvas at once." COOKHAM CHURCH  CLIVEDEN WOODS Apart from "The Bathers" and other paintings which need not be recalled, it must be pointed out that two other notable pictures owe their inspiration to this village and its neighbourhood. One of these was "The Street, Cookham," which has been truthfully characterized as "one of the best of those more spontaneous designs in which the artist treated a simple subject with no other aspiration than to express by legitimate means all its natural beauty. With a well-suggested continuity of onward movement a young girl drives before her, through the broken-down red-roofed houses of the winding village street, a flock of cackling geese." The time-worn cottages which form the background of this picture were in full view from the windows of Walker's own abode, and, as he was not able to finish the picture at Cookham, three of the village geese were sent specially to his London studio for final observation there. Far more important in the record of Walker's fame was the other painting, "The Harbour of Refuge," which owes so much to the near-by village of Bray. With the public at large this is the most popular of his pictures, and no pilgrim to Cookham should fail to extend his wanderings to Bray, where may be seen that restful almshouse quadrangle which the painter selected as the setting of his theme. Many pens have essayed a description of this famous canvas, but none with so much sympathy as that of Richard Muther. "The background," he writes, "is formed by one of those peaceful buildings where the aged poor pass the remainder of their days in meditative rest. The sun is sinking, and there is a rising moon. The red-tiled roof stands out clear against the quiet evening sky, while upon the terrace in front, over which the tremulous yellow rays of the setting sun are shed, an old woman with a bowed figure is walking, guided by a graceful girl who steps lightly forward. It is the old contrast between day and night, youth and age, strength and decay. Yet in Walker there is no opposition at all. For as light mingles with the shadows in the twilight, this young and vigorous woman who paces in the evening, holding the arm of the aged in mysterious silence, has at the moment no sense of her youth, but is rather filled with that melancholy thought underlying Goethe's 'Warte nur bolde,' 'Wait awhile and thou shalt rest too.' Her eyes have a strange gaze, as though she were looking into vacancy in mere absence of mind. And upon the other side of the picture this theme of the transient life of humanity is still further developed. Upon a bench in the midst of a verdant lawn covered with daisies a group of old men are sitting meditatively near a hedge of hawthorn luxuriant in blossom. Above the bench there stands an old statue casting a clearly defined shadow upon the gravel path, as if to point to the contrast between imperishable stone and the unstable race of men, fading away like the autumn leaves. Well in the foreground a labourer is mowing down the tender spring grass with a scythe — a strange, wild, and rugged figure, a reaper whose name is Death." This note of "fragrant lyricism" is the most dominant characteristic of Walker's work. To him it was given to uplift the simplicities of rural life, whether in labour or repose, into the realm of pensive imagination. But, as J. Comyns Carr has insisted, Walker was never tempted "to disturb the sweetness of outward nature in order to bring it into sympathy with the sadness often imagined in his figures. He allowed the contrast to take its due effect; and, however serious or pathetic the influence of his design, he never forgot the delicate beauty of the flowers, or the intricate delicacy in tree-form and foliage." Much of this gift he owed to his communing with nature amid the fields of the Cookham country side. He paid many visits to the Highlands of Scotland, and spent one winter in Algiers; but the former were excursions in quest of fish, and the latter journey was undertaken in search of health; the grandeurs of the Highlands and the light and colour of Algiers held no appeal to his art. Indeed, on one of his visits to Scotland he wrote: "I often think of the peaceful meadows and gigantic shady trees about Cookham (even though I have been away so short a time) and compare the scene with this. No language of mine can draw the difference." Although more than a generation has passed since the artist was laid in his too-early grave in Cookham churchyard, there are still a few natives of the village who can speak of him from personal recollection. They all agree in describing him as a shy, nervous man, and are at one in their testimony as to his dislike to being overlooked when at work on a canvas. It was always the same. An old farmer of another village said: "What a way he was in if any one passed and tried to look! Why, he made nothing of taking up his picture and running into the house with it. You know he got my missus to stand a bit, but she nor I nor none of us never got a chance of a look at what he was a drawing." No artist worked more assiduously in actual contact with nature than Walker, a fact which does much to explain the harmony which persists between his figures and the landscapes in which they are placed. It is more true of him than of Millet that his "landscapes are animated by men; but not by men who are accessories, as is the case with Corot, but by men who are a part of the landscape, its most important and essential part precisely as the trees and clouds are, but more dignified and spiritual than trees or clouds." The testimony of one of his friends, to the effect that he would work under circumstances of physical discomfort such as would have made painting impossible to most men, is confirmed by many stories still told of him at Cookham. FRED WALKER'S GRAVE Perhaps this devotion to his art hastened his end. Consumption was inherent in his family. Seven years before his own death a younger brother had fallen a victim to that ruthless disease and had been buried at Cookham; and hardly had he been dead a year when his greatly loved sister Fanny succumbed to the scourge and was laid to rest "by those she loved." Early in May, 1875, Walker and an artist friend departed for the Scottish Highlands for a short fishing trip. They made their headquarters at St. Fillans by the side of Loch Earn, and there the sudden call came for Walker. Hemorrhage of the lungs set in almost without warning, and a few days later, on June 4th, the gifted artist, whom Millais described as "the greatest painter of the century," breathed his last. The final scene of all shall be told in the language of his brother-in-law, Henry George Marks, whose Life of the artist is a singularly affectionate and affecting tribute. The funeral took place at Cookham on Tuesday, June 8, the remains having been taken down over night. A bright fresh morning, contrasting with the sadness of our errand, ushered in a day such as Walker loved. The coffin was taken to the little sitting-room in the cottage of one of his old Cookham friends; and there, later in the day, came those whom love of him and of his work had brought from town. But for the short notice more would have been present at his funeral, though no numbers could have added to the impressiveness of the scene — impressive from its absolute simplicity. As we stood around the open grave and saw the sheep browsing among the grassy mounds, glimpses here and there of the river he delighted in, the wealth of early summer lit up by a glorious sun; in addition to their affection for the man, none but must have felt the pity of it that the painter whose figures had found fit setting in such surroundings, whose insight had revealed to us new meaning in rural scenes and rustic labour, whose unsullied art had been a brightness in our lives, should have been taken ere he had reached the fulness of his prime. After more than twenty years have passed, one who was present writes: 'The way in which all gave way to uncontrollable emotion, which found its vent in tears, was an incident never to forget.' " THE WALKER MEDALLION IN COOKHAM CHURCH In addition to the simple head-stone which marks his grave — the grave he shares with his brother and devoted mother — the memory of Walker is perpetuated in Cookham church by an exquisite medallion portrait executed as a labour of love by H. H. Armstead. These have their uses for such as need them, but the informed visitor to this lovely district will find himself murmuring the old words: Si monumentum quœris, circumspice. |