|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

ELIZABETHAN WARWICK

THE HEART OF BEAUTIFUL ENGLAND

The heart of Beautiful England is woody Warwickshire, and the heart of woody Warwickshire is leafy Leamington.

To these two towns on the ever-green skirts of the now seared and wasting remnants of the once great Forest of Arden -- the one so reminiscent of the coloured age, of Shakespeare, of Queen Elizabeth, of half-timbered dwelling, of picturesque gable, of shady penthouse, of ever-living poesy, made by the Prince of the Line; the other so sweet, clean, leafy, and spick and span, and as modern as my Lady's newest creation in costumes from gay Paris -- all people gravitate from the farthermost corners of the earth, from Dan to Beersheba, from China to Peru.

Though only two short, leaf-fringed miles apart, linked together by proximity, by association, by friendship, they represent the difference between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries -- the old world and the new; and I think in the whole of Beautiful England you could scarcely find the antique and the youthful so happily -- so prettily -- married, as it were, to each other, and living their lives in such close and affectionate harmony together, as typified by these two towns -- Elizabethan Warwick and leafy Leamington; the one overlooking the classic Avon, in the crystal waters of which Shakespeare laved his youthful limbs in the glow of his life's summer morning, the other upon the banks of the elm river from which it derives its name.

Now, though mankind, the superior creature of the world, loses by increase of years, and is to-day accounted too old at forty, age is a positive recommendation to a town -- a town the creation of man, who is now accounted too old at forty! In respect of years, therefore, I, who do not subscribe to the modern slander against age, shall place Warwick -- venerable and crusted like old wine -- first, before the green and youthful Leamington, though each has beauties of its own; and shall personally conduct my readers to the antique town which, under its frowning East Gate, gave birth to a Landor -- Landor, whose Imaginary Conversations seat him amid that literary galaxy encircling the fixed star, Shakespeare.

Sir Walter Scott, who loved Warwickshire, and sojourned both at Warwick and Leamington in the early years of the nineteenth century, gathering materials for and writing his romance of Kenilworth, tells us that

|

If thou wouldst view fair Melrose aright, Go visit it by the pale moonlight. |

Sunlight, however, is the proper luminant beneath which to visit Warwick, and the right way to approach it is from the west, coming straight from the fringes of Shakespeare's greenwood, through picturesque Charlecote -- where the poet "ill-killed" Sir Thomas Lucy's deer -- and straggling Barford, under woodland trees all the way, with glimpses of the romantic Avon flashing in between.

Standing at the foot of West Street, looking eastward up the stony ascent, a picture of the past Warwick touches curious hands with the present. Right before the eye, crumbled and lichen-grown, yet grand even in its decay, towers the Western Gateway of the anciently-walled town, perched upon a steep elevation from which a splendid panorama of the classic and pastoral Shakespeare Country may be seen -- a position which in the days of Cavalier and Roundhead rendered Warwick impregnable to the besieger on this side. This is the hoary gate shutting in the town from the west. Pass under the open arch, which looks diminutive by contrast with the depth of space from its apex to the summit of the grey tower, and you are immediately a figure in an Elizabethan scene, and are now walking in the footsteps of the Maiden Queen and her favourite, Robert Dudley, brother to Ambrose, "the Good Earl" of Warwick.

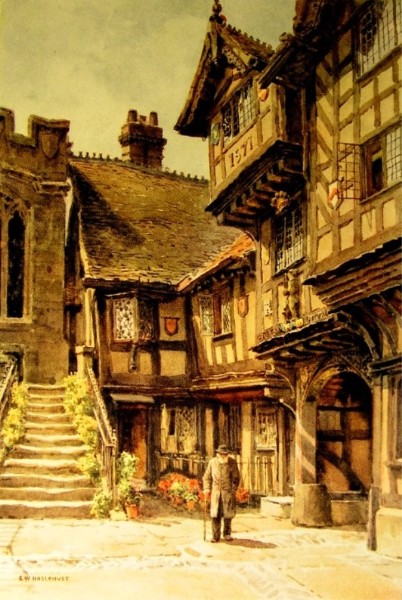

And there, after mounting a few yards of a crooked street, steep as a precipitous pathway on Cader Idris, you see before you, upon a terrace fringed with green and shady limes, the one charitable act and dedication in the life of this same Queen's favourite and lover -- the picturesque, even ornate, building which, through the centuries, bears his name and escutcheon, "Leycester's Hospital".

This House of Refuge for the declining years in the lives of "twelve impotent men" is one of the architectural gems of old Warwick -- indeed, of all England. It speaks of the coloured age, of fanciful costumes, of rich, permanent, and imposing building, and in appearance is a strong link uniting to-day with the days of Shakespeare -- and beyond, with the still earlier times of chivalrous and noble deeds. Overlooking the inclining street, this heirloom of the ages bursts upon the gaze of the present-day sightseer with all the attractions of a picture of the antique world; and yet a pictorial creation out of date, when within seeing distance of the gaudy electric tramcar, and within earshot of the unmusical creaking of the car's wheels, grinding a stone to powder in the metal groove only a few yards away.

One of the best-known specimens of ancient building in the whole pictorial history of architectural England, Leycester's Hospital is not the erection of the powerful courtier whose name it has borne so proudly through the past three centuries. This picturesque fabric -- the joy of every lover of the painter's brush -- with its half-timbered front, its overhanging gables and rest-awhile seat upon the cobble stones of the entrance, boasts an older date by nearly two centuries than the day of Robert Dudley. It was originally the property of the Guilds of the Holy Trinity and St. George the Martyr, and is considered to have been built about the year 1380) in the reign of Richard the Second. After the Dissolution of Monasteries by Henry Tudor, it was either purchased by or presented to Robert Dudley; and in 1571 this Queen's lover, doubtless as an expiation for some of his transgressions -- notably his light dealing with Amy Robsart -- endowed it as a Collegiate Hospital for indigent and aged men.

Some of these ancient wayfarers down the hill of human life may be seen on any bright summer day resting, and dreaming of what might have been, on the rustic bench just outside the gateway, where tradition says Sir Walter Scott sat and rested during his stay in the adjacent Kenilworth; and over the gateway is the brilliant cognizance of the Dudleys -the Bear and Ragged Staff -- with the motto, "Droit et Loyal". This badge is between the initials "R. L." -- Robert Leycester.

And the interior of this dwelling of the past is as delightful to the eye and the mind as the exterior. Under the gateway and inside the quadrangle the scene is exquisitely quaint and interesting. Ancient gables with white bears and ragged staffs in plenty are there to attract the eye, and on the front of the Master's Lodge, on the north side of the square, are carvings in colour of the Bear and Ragged Staff. The principal apartment in the edifice, the Great Banqueting Hall, has, alas! not escaped the destiny of all things mundane. Often the scene of princely gatherings, and once at least the theatre of a royal feast, with King James the First as chief guest, this grand room became reduced to the base uses of a laundry, where the maids looked up from their work to roof timbers elaborately carved in Spanish chestnut wood! Over the hoary and now ruinous West Gate -- the erection and gift to the town of the celebrated Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, in the reign of Richard the Second -- to which every visitor with antiquarian leanings casts a lingering look when leaving the gateway of Leycester's Hospital, is the small chapel of St. James's, perched up nearer the sky. Here, to this day, the venerable recipients of Robert Dudley's bounty meet together for daily prayers, under the eye of the chaplain. There are twenty-two oaken stalls for them -- eleven on each side. The chapel is a fit appendage to the hospital; both are redolent of ages ago, coloured with the glamour of history, and beautiful in their decline; while from the windows of the chapel upon the tower sweetly panoramic views of Edge Hill and other places of interest in the Shakespeare ring of villages can be clearly seen on any bright summer's day.

Another look back at this felicitous picture of life in Warwick five centuries ago, and you step into the life of the High Street of the town to-day -- much the same as it is lived everywhere, perhaps, but with an old-world air and a sense of slowness clinging to it admirably in keeping with private dwelling-houses here and there, speaking of different dates, different builders, different lives -- with a century or two between them.

This is the charm of old Warwick and a wander through its streets; the charm of variety in architecture, in ideas, in associations; the charm of fancying that at any moment an Elizabethan beauty, clad in hooped gown, a frilled collar round her neck, and her beautiful hair built up to the height of a miniature tower, might at any moment step out from a doorway -- say from the doorway of the ancient inn, "The Bear and Ragged Staff" (correctly "The Bear and Baculus"), quaintly perched upon the High Street's point, and looking straight through the gateway of Lord Leycester's Hospital-and walk with stately grace to her sedan chair, held in the hands of two carriers, waving her feather fan the while to divert male attention from her maidenly blushes.

The High Street and its continuations -- Jury Street and Smith Street -- cut Warwick in half in a direct line, a line of highway which, connected by tramway, leads right on to leafy Leamington, through that sister town, and to the eastern village beyond, leaving the Castle and the Avon on the south side and the Church and Market-place on the north.

Passing house and shop and reaching the corner of Church Street just midway between the two famous Gates of Warwick, the West and the East -- and looking up the northern turn, the beholder is again, as it were, a lay figure in a picture of Elizabethan days.

Church Street is steep and crooked, and the fine Tower of St. Mary's -- "Warwick High Church", as it is known in the provincial tongue -- is built right over the roadway; so that you look up a quaint old street at the end of which, and forming a noble ecclesiastical background to the scene, stands the tower of a magnificent cathedral-like church, directed towards the sky, high above everything else, with an archway beneath it through which everyone must walk in History's enchanting footsteps.

Founded in the reign of Stephen of Blois by the de Newburghs, the first Norman possessors of the Castle, St. Mary's was remodelled by Thomas Beau-champ, Earl of Warwick, who, before the design was completed, passed away, leaving the work in the hands of his son, by whom this glorious ecclesiastical pile was finished, as it then stood, in 1394. In exactly three centuries from that date this noble fabric encountered a kind of dramatic romance -- its tower, nave, and transept being destroyed by a fire which, on September the 5th, 1694, burnt out a great portion of the anciently walled town, leaving only one street -- Mill Street, on the south of the Castle -- untouched and perfect, as a purely Shakespearean street which the feet of the poet himself must often have trod. The present edifice of St. Mary's was erected as it now stands by public subscription in the reign of Queen Anne, being restored after the burning by Sir William Wilson, of Leicester, from plans which had been drawn, but which were not fully carried out, by Sir Christopher Wren, the famous architect, who at that time was living at Wroxall Abbey, a beautiful estate a few miles distant from Warwick.

The full grandeur of this religious fane, imposing as it is from the outside, is seen within. Here are the long-drawn aisles, the high-backed stalls, the carved angels, the white cherubims, the risen altars -around which kings, queens, and princes have stood -- the earls and countesses in brass, the high-pitched windows filled with pictured saints in colours, and many other ornaments which impress the passenger as he enters, and make him stay. Indeed, the beauty of St. Mary's is married to an enthralling solemnity. Whichever way the eye turns are signs and symbols of a sanctuary rich in all that refines the mind and soothes the soul.

St. Mary's Church consists of nave, aisles, transepts, chapel, and Lady Chapel, with chantry and oratory -- with, as I have said, a magnificent tower at the west end. At the termination of the nave is the choir, entered through wrought-iron gates and covered with a beautiful ribbed roof, the style of architecture being the Decorated. In the centre of the choir a fine monument attracts the eye -- a superb tomb surmounted by figures of Thomas, Earl of Warwick, founder of the sanctuary, and his Countess, Catherine Mortimer. From the choir the silent mover in "the dim religious light", as Milton calls it, of this splendid God's House will pass to the Lady Chapel, or, as it is more commonly called, the Beauchamp Chapel. No one, being at Warwick, should ever miss seeing this ineffably beautiful example of pure Gothic. The ceiling of the chapel is of richly-carved stone, the floor of black and white marble, laid in the shape of lozenges. Here you may look upon the glorious altar tomb of Richard Beauchamp, the founder of the chapel; and just outside, on the north of the chapel, is the equally magnificent monument, of the altar kind, covering the bones of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Beneath a rich canopy, supported by four Corinthian pillars, lie the recumbent figures of the Earl and Lettice Knowles, his third Countess; but nowhere here is the figure of the hapless Amy Robsart, around whose life Sir Walter Scott has woven such a glamour of romance. She lies elsewhere; but her sad spirit seems to hover about the monument of the courtier whom she loved so fondly and so vainly, and who is accounted to have used her so ill.

The Beauchamp Chapel

Tombs of the Founder and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Indeed, look where you will in this grandly impressive fane, you will see sights to soften the heart and bewitch the eye, for St. Mary's at Warwick, the massive tower of which stands like a sentinel of the ages keeping watch and ward over the town, is a veritable ecclesiastical palace.

Before leaving this hallowed spot, this pile of carved stone, there are still two things to observe as roundings-off to felicitous harmonies -- something to see and something to hear, and both resident in the imposing campanile. No one, for instance, will willingly forego a climb up the spiral stone staircase of the tower, even only imagining the reward of it, for the panorama revealed from the top -- a bird's-eye view of Beautiful England's pastoral heart -- is so glorious as to be worth many miles of upward journeying; and few modern humans are so unmusical as not to wish to hear the songs of the bells, pealing from the tower upon each four-hours' stroke, and according to the day, the tunes of such charming ballads as "Home, Sweet Home", "The Bluebells of Scotland", "There's nae luck aboot the Hoose", and "The Warwickshire Lads and Lasses". There is a tune for every day in the week, "The Easter Hymn" being chimed on Sundays, and the effect, coming to the ear in a scene and town so reminiscent of Elizabeth and Shakespeare, is charming indeed.

Those in love with the things of the nether world may, after their ascent of the tower, like to go down into Hades -- into the Great Crypt of St. Mary's. This is entered from the churchyard, is beneath the choir, and is very interesting, being probably a part of the ancient building. Here, at the north-eastern end, is the burying-place of the Earls of Warwick; and here, too, is the old-time ducking stool, which used to be employed for punishing, and cooling the hot anger of, the fair Warwickshire scolds -- a relic of bygone life looked upon with a smile by beauties of to-day, happier in their emancipation from the ruder penalties of the marriage bonds than their sisters of the past.

Skirt the church now and go westward through the old Square, upon which the tower looks with a quiet and a solemn eye, past the Post Office, and in a few steps you are walking in the ancient Marketplace of Warwick. Almost a complete square, with, at the south end, a market hall and a wonderful museum above it, in which there are collections of rare "finds" given up by the earth's crust in many parts of historic Warwickshire, this Market-place is the theatre in which the annual Hiring Fair is played, where it has been played, indeed, for the past 600 years -- for the first "Three Dayes Faire" was established on this very site in 1260 by John de Plessitis, husband of the valorous Margaret de Newburgh. Here, on Fair days, the possessors of the stately Castle, whose massive towers look on these worldly things with dignified silence, have stepped down from their golden chairs and mingled with the Fair gatherers; and upon more than one occasion, my friend, the present gentle and sympathetic Countess, casting aside for the moment the pride of birth, breeding, and estate, has come among her own people of Warwick and partaken of a juicy slice cut from the fat ox which every year is browned upon a spit at the south-western corner of the Market-place.

Such a scene, the aristocracy and the democracy mingling together on Fair days in the public market, is a sign that, after all, the division between gentle and simple is not so deep as a well nor as wide as a church door -- in Warwick, at least; for these happy minglings of caste have occurred here for centuries, and are more than ever likely to continue in the future. A little hiring -- a very little -- is done in the Warwick Fair now, and this little in the morning, the day being almost entirely given up to the pursuit of pleasure. In his well-known Warwickshire novel, A Bunch of Blue Ribbons, the writer of this description has laid one of his scenes in the Marketplace of Warwick during a Fair day.

After a walk round the Square and a peep, perhaps, in the museum for any who love the things of the older world, let us retrace our steps -- though treading, as we are, where kings and queens have trod -- and, moving northward past the church and Shire Hall, with its long facade and Corinthian pillars, glance for a moment at the very interesting building at the end of Northgate Street -- from which the North Gate has entirely disappeared -- called "The Priory".

Upon this spacious arid sequestered parcel of land once stood the Priory of St. Sepulchre, founded by Henry de Newburgh in the reign of Henry the First, and replacing the still more ancient Church of St. Helen's.

This was a grand and rich religious house, greatly fostered and cherished by the Earls of Warwick until the Dissolution, when it was bestowed by John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, upon his trusted retainer, Thomas Hawkins, whose father was a merchant and sold fish at the Market Cross near by; and he, demolishing the monkish building, erected a beautiful Elizabethan mansion upon the site -- a veritable book of historic associations a few leaves of which I will open.

Here, in this "Hawke's Nest", as the owner called it, partly from his name and partly from the splendid grove of Warwickshire elm trees in which it is placed, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, spent several days in 1571 as the master's guest, and in the succeeding October the Marquis of Northampton, brother of Queen Katherine Parr, died here. A still more notable – and pretty -- incident occurred in this delightful homestead on the 17th of August, 1572, when Queen Elizabeth, coming from the princely revels of Kenilworth, surprised the Earl and Countess of Warwick at supper here and sat down with them to the meal, afterwards visiting the good man of the house, who at that time "was greviously vexed with the gout".

With the passing of Hawkins and his reprobate son Edward, who in the short space of four years entirely dissipated the vast fortune left him by his father and ultimately finished his career in the Fleet Prison, the historic glory of The Priory departed. In 1709 it was purchased from the successors of the ill-fated Puckerings by Henry Wise, Court Landscape Gardener to Queen Anne, who laid out the beautiful gardens of Hampton Court Palace, and was gracefully lauded for his floral art by Addison in The Spectator. This historic and ancestral home of Beautiful England subsequently became the possession of Thomas Lloyd, the banker, descendants of whom inhabit it at the present time.

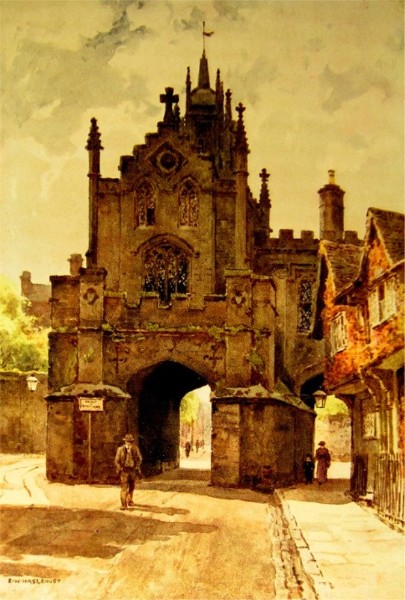

Returning through the archway of St. Mary's Tower, descending steep Church Street, passing the Court House on the right, erected in 1730, and bearing round eastward into jury Street, the beholder now looks down a narrow street, on each side of which here and there are dwelling-houses preserving their Elizabethan aspect, and at the farther end of which, looming up like the background to a stage scene, stands, in all the grandeur of centuries of decay, the ancient East Gate of the town -- all, indeed, that remains of a building ornamental and strong in its birth and dignified in its death.

As on the West Gate there is a chapel to St. James, on the East is one to St. Peter, built in the reign of Henry the Sixth. But before taking the East Gate way, as that is the way out of Warwick and on to Leamington from our position as we now stand, come with me a slight detour southward -- where now there is no gate, but instead a beautiful stone bridge marking the southern boundary of the town -- and I will take you, gentle reader, to the princely Castle of Warwick, which is within the town's boundary, and should therefore be seen as a part of it; the Castle whose two magnificent towers, which, as Landor truly said, "don't match", point out to you as you move along the presence of one of the most glorious feudal piles now existing in Beautiful England.

A few short steps only from the grey and lichen-clad East Gate, led thither by the stone wall bounding the domain from jury Street to Mill Street, and we are before the great gatehouse of Warwick's Castle -- that famous Warwick, I mean, Richard Neville, who made and unmade kings, and died on Barnet Field from the cruel sword-thrust of his own much-loved son-in-law, Richard, Duke of Gloster, afterwards Richard the Third; though the Castle is not now as it was when the Kingmaker held Court there, and Gloster, with his brother Clarence, sweet-hearted the master's fair daughters.

Here the pilgrim to Warwick really is in the very footsteps of Shakespeare, for "Stratford's wondrous son", at the age of eleven years, stood with his father, John Shakespeare, by this very Porter's Lodge, watching the gorgeous incoming of the queenly Elizabeth, escorted by her haughty favourite, Robert Dudley, just returned from perhaps the greatest pageant that the world has ever seen -- "The Princely Pleasures of Kenilworth". And from the Porter's Lodge to the interior of Warwick Castle -- that imposing feudal erection of Sir Fulke Greville upon the ruins of Ethelfleda's fortress, and, in this year of grace, the possession of Francis Richard Charles Guy Greville, fifth Earl of Warwick -- is but a step through a winding roadway carved out of the solid rock; and here are such wonders gathered under one roof as the spectator will scarcely find beneath any other dome in the world.

Time is needed for the survey of these treasures, for rapid movement destroys the effect of a picturesque and mediaeval environment -- of a transition from the twentieth century to the epoch of the romantic Guy?

Earl of Warwick and his Guy's Cliffe bride, the fair Felice. A few brief facts, however, must be noted to give a colour scheme to my picture of this architectural legacy of the centuries.

Through Saxon and Norman possessors the Castle and estates came, by grant from James the First, into the ownership of the scholarly Sir Fulke Greville, first Lord Brooke. At that time the Castle, having come through shocks of war with the Barons and at other periods, was in a condition of semi-ruin. This Sir Fulke set out to remedy. Expending ₤20,000 in repairing and embellishing the Castle, he, in the words of Dugdale, the celebrated Warwickshire historian and antiquary, "made it not only a place of great strength, but of extraordinary delight, with most pleasant gardens and thickets, such as no part of England can hardly parallel; so that now it is the most princely seat that is within the midland part of this realm". The present fabric, therefore, may be called the Castle of Sir Fulke Greville; for, though it withstood a siege in the Cavalier and Roundhead wars of 1642, and also an alarming attack of fire in 1871, no material difference has been made in its aspect since the reign of King James.

The towers "that don't match" are of more ancient date. Caesar's is generally considered to be the oldest portion of the entire building, and is, though conjecturally, ascribed to the hand of Julius Caesar. It is a monument of strength, reaching an altitude of 147 feet. Guy's Tower, named after the giant earl, looks even more imposing than Caesar's, but this may be from the fact that it is built upon a rocky elevation. This tower -- Caesar's is now too dangerous -- may be ascended by those who love climbing, and the extremely fine view from the summit is worth the toil of reaching it. I am happy to have waved my cap from the top of both.

Not a tithe part of the wonders to be seen in Warwick Castle can be enumerated within the compass of a short description. None, however, will be wise to miss an examination of the Great Hall and its collection of arms and armour, or of the many relics of the life of that extraordinary being -- whether real or imaginary does not much matter now, since he has become canonized as one of the nine wonders of the world -- Guy, Earl of Warwick. The gorgeousness of the interior of the Castle can scarcely have more attractiveness for the sightseer than the enormous Porridge Pot of the Giant Guy and his pieces of armour -- his sword, shield, breastplate -- and walking-staff. It is said that this gigantic pot was used as a "punch bowl", and thrice filled and emptied at the coming-of-age festivities of the father of the present earl. When I say that this bowl holds 120 gallons, it will be seen that hospitality was not lacking in generosity at Warwick Castle that day.

The great Baronial Hall is a splendid apartment, 62 feet long by 35 feet wide, from the windows of which bewitching views of the surrounding country can be obtained; and in the Banqueting Hall, gorgeous with carving and gilding, is to be seen the celebrated "Kenilworth Buffet", made entirely out of a colossal oak grown in the grounds of Kenilworth Castle. Indeed, this feudal home of Sir Fulke Greville contains such a collection of priceless treasures as may not be found under any other roof in Europe, not the least priceless of which is the Library, with its unique Shakespeare memorials and copies of the First and Second Folios. Happy -- thrice happy -- the Earl and Countess of Warwick with a home like this to offer to the eyes and the intellect of students of England's history -- from ten o'clock in the morning to half-past four in the afternoon -- for a sordid fee of two shilling coins of the realm!

We leave the Porter's Lodge now and move into Mill Street, a few paces southward, and here you are walking in one of the finest Shakespeare streets to be seen in England to-day. Go to the bottom of this ancient street of the mill, where the classic Avon laves the base of the Castle, look upward, and there gather an idea of the amazing height, strength, and permanency of this old-time fastness of Merrie England. Then, for a final view of the exterior, we climb the southern hill to the Castle Bridge at the meeting of Myton Road, which is part of the old London coach road, and runs through Leamington. Here, upon this bridge, the wide and clear Avon comes directly upon the vision, fringed each side with luxuriant and many-coloured foliage, and seems, as it were, the waterway to the Castle, for the noble building shuts in the picture -- appearing as a magnificent natural background to it.

Now to the grey East Gate again on our way out of Warwick. Pass through the archway to the eastern side, and there, wedged up close to it, are two of the prettiest little Shakespeare dwellings, abutting upon the pathway and approached by a few stone steps, that you could ever expect to see outside a modelling in Dresden china. These, with their beetling gables and half-timbered fronts, will attract the eyes of all loving the picturesque in architecture; and a few steps beyond you will see, in a tall house of faced stone -- a dwelling apparently of the Georgian period -- the remarkable difference in styles of building in Warwick, a difference to which I have before alluded, and which is one of the happy -- or unhappy -- charms of the place.

This handsome stone house of flat windows at the corner of Chapel Street, now used as a ladies' school, standing well within the shadow of the East Gate, was the birthplace of that erratic genius, Walter Savage Landor, who first saw the light of the world here in 1775 -- as notified by a tablet on the house front -- and was afterwards rusticated from his college for firing a pistol in the quadrangle, but who, as a set-off to this boyish freak, wrote the immortal Imaginary Conversations. Years afterwards Robert Browning found Landor stranded at Florence, and there, in that lovely Italian town, this virile spirit, with almost a Shakespeare tongue, passed away after a stormy career, singing as he went –

|

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife, Nature I loved, and next to nature Art; I warmed both hands before the fire of Life; It sinks, and I am ready to depart. |

There is a bust to his memory placed by his son in St. Mary's Church in 1888 from the chisel of the eminent sculptor, Forsyth.

Before entirely leaving Warwick by the narrow and declining Smith Street, let us not miss a peep at Guy's Cliffe, which, though outside the town, is permanently knit in with the town's history. The way to this romantic "haunt of the Muses" is by Coventry Road -- the first northern turn from Smith Street, and immediately opposite the ancient gabled house known as the Hospital of St. John's. This very interesting building, with a good Jacobean staircase, was erected by William de Newburgh, Earl of Warwick, in the reign of Henry the Second, "for entertainment and reception of strangers and travailers, as well as for those who are poor and infirm".

The Coventry Road to Guy's Cliffe is a royal and a literary road. Kings, queens, princes, poets, painters, and authors have trodden it; also that luckless king's favourite, Piers Gaveston, whose comely head fell from his shoulders upon Blacklow Hill, a few yards from the Cliffe, on 27th of June, 1312, by order of that grim Earl of Warwick whom he in sport had called the "Black Hound of Arden". And this is not all. Up and down this Coventry Road, in the years 1722-3, tripped that wonderful little girl, Sarah Kemble, then only "sweet seventeen", who was destined, as Sarah Siddons, to become the greatest delineator of Shakespeare's women characters that the world has ever seen. She was maid-companion to Lady Mary Greatheed at Guy's Cliffe for less than one single year.

Let all fair pilgrims note the postern door in the stone wall of the Cliffe grounds, near the picturesque Saxon Mill, with its decorative wooden balcony, where John Ruskin loved to linger, listening to the soft music of the mill wheel; for through that door, on 25th of November, 1773, "the divine Sarah" eloped with her lover, William Siddons, the worst actor in Roger Kemble's Company of Comedians, trudged afoot with him to Coventry, and was "fast married" to him in Holy Trinity Church there -- and no one any the wiser until the deed was done!

And there, looking westward down a long avenue of Scotch firs, forming a picture-like theatre almost unexampled in England, is the romantic abode of Guy's Cliffe -- the ancestral seat of the Greatheeds, the Berties, the Percys, and now the possession and home of Lord Algernon Percy, brother of the Duke of Northumberland.

Guy's Cliffe dates a very long way back into the centuries, though the present mansion is no older than the year 1822. It has that absorbing romance associated with it of Guy and the fair Felice; and though some learned antiquarians of these later ages speak and write of the renowned Guy as a myth, the legend, if it is one, is so closely woven into the hearts of the people that it will not be exorcised. Guy's Cave is indeed shown there to this day on the north side of the Cliffe; there is also his gigantic statue in the chapel -- the latter erected in the reign of Henry the Sixth; in fact, the whole mansion and grounds are redolent of the brave Giant and his martial doings, whether they be fables or true; and the beauty of the Cliffe is a very poem in scenes.

"It is the Abode of Pleasure; a place delightful to the Muses. There are natural cavities in the rock, small but shady groves, clear and crystal streams, flowery meadows, mossy caves, a gently murmuring river running through the rocks; and to crown all, solitude and quiet, friendly in so high a degree to the Muses."

This spirited description of Guy's Cliffe by John Leland, the antiquary and contemporary of Shakespeare, written in 1540, will be endorsed by every visitor to the scene to-day, none of whom are likely to omit seeing Gaveston's Monument on Blacklow Hill, only a short distance northward from the mansion. The pedestal can be seen from the roadway, peering out from a garment of foliage on the tangle and tree-crowned Hill. There is a tradition that Shakespeare halted in this romantic scene when taking his memorable tramp to London. Whether this be the fact or not, the rambler to historic Guy's Cliffe will certainly fail to see all the objects of interest if a call is missed at Blacklow Hill and Gaveston's Monument upon the crown of it.

Retracing our steps down the Coventry Road, we now leave Warwick by the main highway running in a direct, leaf-fringed line to Leamington, casting a lingering back-look upon the towers of the princely castle, which are watching us all the way. We are now changed from a mediaeval and Shakespearean to a twentieth-century environment, which the electric tramcars, passing at frequent intervals, are not likely to make us forget. Crossing the Avon by the Porto Bello Bridge at Emscote, I shall conduct my readers to leafy Leamington by the Rugby Road as far as the Kenilworth Road, thence a little down this handsome roadway to the top of the Royal Parade, which is the best and most correct mode of entering this pretty, clean, and green heart of woody Warwickshire.

Click the book image to continue to the next chapter