|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

LEAFY LEAMINGTON

THE HEART OF WOODY WARWICKSHIRE

Were Touchstone in the flesh now, and standing with a modern Rosalind and Celia in front of Christ Church, looking down as fine a sweep of Parade-way as any to be seen in Europe, he would not say, as Shakespeare made him,

"Now am I in Arden",

but he would say,

"Now am I in Leamington,

And couldn't be in a better place".

And he would be right. On every hand "this Bethesda of the Midlands ", as it has been aptly called, is girt in with sights and scenes -- all so different, indeed, from those of Warwick -- which have an enthralling attraction for pleasure-seekers, for those seeking a garden which is always in leaf if not in flower, always a home for the homeless all the year round. For from leafy Leamington every old, historic, and romantic spot in the whole of Shakespeare's classic land can be visited and inspected in a day's ride in carriage, coach, or motor car. Many places, indeed, may be visited on foot, one being the rustic village and church of Lillington, where Nathaniel Hawthorne, the famous American writer, so loved to wander and to linger.

As we stand here upon this northern height, looking with admiration down the Parisian-like boulevarde of the Parade, where every association seems in keeping with a smart and gay town, almost in advance of civilization instead of behind it, let us just peer into the near past -- the very near, as centuries go -- and see what the history, if the romance of Leamington can be dignified by the title of history, of the town really is.

Though it goes back in actual life to pre-Norman times, the real history of Leamington is the history of a single century. At the beginning of the nineteenth century it was yet a village, snug farm-houses then occupying the site of the present Royal Parade down which we are gazing. In still earlier days Leamington was the possession of the Priors of Kenilworth, and legally retains the name of "Leamington Priors" to the present day. But with its ancient appearance and usages I have little to do in this description more than to recount them briefly, as the beginnings of a picture. Leamington has now no monks and friars walking in its streets as the monks and friars of old used to walk in its fields and lanes. Less than a hundred years have made a complete metamorphose in its appearance and people; and if the venerable fathers who once held possession of the rustic village could visit the scenes of their former abode, they would feel like strangers in a strange place, and would go sighing back to their graves -- screening their eyes, with a muttered Retro Satanas, from seeing the many beautiful Leamington lasses in hobble skirts promenading the extensive and fashionable Parade.

No semblance of what it was in the year 1808 yet remains in the physical aspect of Leamington -- nothing but the leaves, and trees, and flowers; they are there still, and always should be. What the state of Leamington was in 1808 is well described in his diary by William Charles Macready, the celebrated tragedian, who had more than a passing acquaintance with the town in its village days -- when, like Peter Pan, it had not "grown up". These are Macready's words:

"Birmingham was the most important town of which my father held the Theatres, and there we soon arrived. The summer months were passed there, diversified by a short stay at Leamington, then a small village consisting only of a few thatched houses -- not one tiled or slated; the Bowling Green being the only one where very moderate accommodation could be secured. There was in progress of erection an hotel of more pretension, which, I fancy, was to be the Dog or Greyhound, but which had some months of work to fit it for the reception of guests. We had the parlour and bedrooms of a huckster's shop, the best accommodation of the place; and used each morning to walk down to the Springs across the old Churchyard, with our little mugs in our hands, for our daily draught of the Leamington Waters."

There is not now in Leamington one single cottage left with a thatched roof, sad as this may be for the clever and earnest artist who is figuring Beautiful England in colours, that primitive but picturesque house-covering being discountenanced by the local authorities in 1843. But change has made the town really prettier even than it was in its palmy days, when George the Fourth, "the First Gentleman in Europe", following the suit of Macready, imbibed his glass of Spa water at the Pump Room, and then returned to the princely Castle at Warwick, of which he was the honoured and royal guest.

And what, or who, was the Prospero that, with the wave of a magician's wand, changed a field of standing corn into an ornate and fashionable Parade -- a sleeping village into an active and royal town? The Prospero was one Benjamin Satchwell, the village cobbler, postmaster, and poet, who found that magic spring of saline water in the earth near the church; that water which was really the magician that brought fame and fortune to this old-time little village upon the Leam, or elm river. The power of this wizard of the earth changed everything. In an incredibly short space of time this obscure village -- end, as it were, rose to be one of the most fashionable resorts in England, being visited by not a few celebrities and many crowned heads -- and at least one uncrowned head, Napoleon the Third.

Two of the first aristocratic families that took up their abode at Leamington a century ago were the ducal houses of Bedford and Gordon. Streets are still named after them both; and though Bedford House has gone, Gordon House remains -- its great grounds built upon, and itself wedged quite out of sight in the centre of new buildings, a striking instance of the vanity of all things mundane. But in those days Merrie England was Merrie England in truth and deed, whatever it may be now; and I may mention here, as an amusing illustration of life in Leamington in its village days, that the Duchess of Bedford frequently led off the country dance on the bowling green, then at the south end of the present Church Street, with Dr. Samuel Parr, the famous Latin scholar, who at that time was curate-in-charge of the interesting little church of Hatton, two miles west of Warwick, where this learned Latinist led a typical country parson's life for forty years -- ringing his own bells, too, for he was an excellent campanologist.

The happy situation of Leamington, in the heart of woody Warwickshire, is doubtless one of the chief causes of its popularity. Though it has no long elaborate history of its own beyond the few features I have stated, it is surrounded with history of the most attractive type. It is this which undoubtedly draws strangers and visitors from all parts of the globe to its hospitable shades. It has the merit, indeed, of being the meeting-ground where all people gather when on a tour to the many pleasing scenes and famous show-houses of historic Warwickshire.

Eleven miles to the west -- leaving the places of immediate interest out of account, as they are so near -- is the classic neighbourhood hallowed for all time by Shakespeare's name and genius. Less than five miles to the north are the spacious Abbey and Park of Stoneleigh, and within two miles farther north the ruined and historic Castle of Kenilworth and the ruined Priory of the great Geoffrey de Clinton. To the east the wayfarer's footsteps may tread the ground of Dunchurch, made famous through its connection with the Gunpowder Plotters; and farther afield still, at Long Compton, are the prehistoric Rollright Stones, the battlefield of Edge Hill, the unique Tudor mansion of Compton Wynniates, the Baronial Hall of Maxstoke, and the three tall spires and romantic Hall of ancient Coventry, and its statues of Lady Godiva.

Thus environed by history and romance such as can scarcely be found in any other town in England, Leamington still has a pretty taste of quality of its own. There are sights to be seen here, magic waters to drink, and, best of all, pure air to breathe; together with an architectural and colour scheme excessively modern, it is true, but full of a pleasing comfort which is its own recommendation. The delightful old-world atmosphere of Warwick, though only two miles away, has not even touched Leamington, which stands, in comparison with its sister town, like a sweet, fresh young child -- wondering how on earth anything can ever grow old.

Leamington is the symbol of perpetual youth clinging to the skirt of crusted antiquity. The town itself is laid out as a garden, and is literally a garden always in leaf and flower, designed so sweetly and simply that the veriest stranger could never miss his way in the parallel streets. In hardly another popular resort in England can be found such wide, clean streets, terraces, squares, and avenues; such luxuriant foliage; such a remnant of a centuries-old woodland, with a rookery in it, too -- right in the town's heart; such gay, more than up-to-date shops and calling saloons; such roomy, well-built dwelling-houses; and such a general atmosphere of health, comfort, prosperity, and pleasure -- for life here indeed seems one continuous dream of pleasure during all the hours of day, and then, beneath the electric light, pleasure again. In short, Leamington, as seen to-day in the second youth, as it were, of its life -- the first was in the early years of the nineteenth century -- may be accounted quite the last word in modern leafy town-planning.

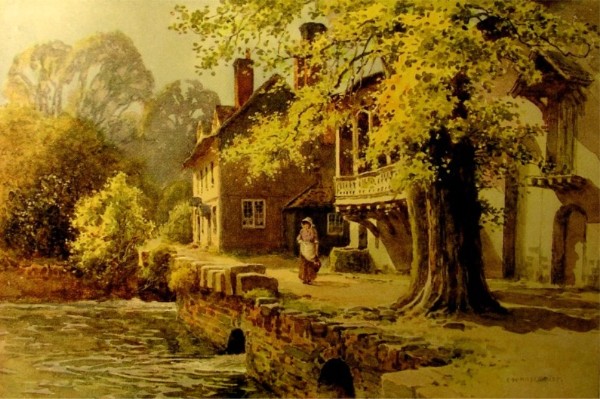

The Leam at Leamington

It was not so in the beginning, when Leamington existed only on the south bank of the river, which cuts the town through from west to east. In those earlier days, builders were not so enlightened as they are now, and were obviously much more grasping in regard to space; for when we consider that the south side of the Leam was, a century ago, the fashionable quarter, and that thither flocked the dukes and duchesses of that generation -- for there also were the Pump Room, Baths, and Wells to the number of ten -- we confess to a feeling of wonder at the easy satisfaction of the older of our nobility and people in comparison with their descendants' almost too exacting requirements to-day. But the south town, with its pinched and crabbed appearance, soon gave place to the north, where the now beautiful and palatial Leamington grew out of the northern earth, as it were, at the stamping of a foot.

And this pleasant resort of fashion, with its finely curving Parade, down which we are wandering with admiration, its aristocratic mansions, its comfortable hotels, its Pump Room, Jephson Gardens, Mill Gardens, York Promenade, and spacious Victoria Park, is only two and a half hours from London, by either railway. Here from the smoke and noise of cities can the dwellers therein immure themselves against the rush and, hustle of modern life which so easily extinguish it.

It was here, in leafy Leamington, that the jaded John Ruskin, not then the celebrity which he afterwards became, stayed for a six-weeks' residence and a forty-two-days' course of the famous spa waters -- in the charge and under the eye of the eminent physician, Dr. Henry Jephson, who has been aptly called "Leamington's Father". This was in 1843, when the town was in the heyday of its first youth; and Ruskin tells us in his Praeterita that at the end of his period of six weeks he was dismissed by his doctor in the following words:

"Sir, you may go; your health is in your own hands". Upon which Ruskin remarks,

"Truly my health was in my own hands, and I immediately reverted, in perfect health, to brown potatoes and cherry pie ".

So much for the health of the author of The Stones of Venice, obtained by resting in Leamington and drinking its waters, and wandering about the northern

elevation. This very fine area of residential Leamington can be well seen upon entering the town, as we did, from Warwick by the Rugby Road. Here are the most charming, wide, and extended avenues, bordered each side with luxuriant trees -- the Kenilworth Road, for a portion of the way, with sweet silver birches; and in Binswood Avenue, a continuation of the Rugby Road, the stranger's eyes look upon what is perhaps the only Tudor-style building in Leamington.

This is the extremely picturesque edifice, erected in 1848, with an artistic cupola at each end, which, when the town was more of a seat of learning than it is now, was the Leamington College, but which, in this year of grace, is the possession of the religious confraternity known as the Sisters of the Sacred Heart -- exiled from France some years ago -- and is used as a convent for the education of young Roman Catholic girls. At least two famous men, if no more, have been immured in the cool shade of this scholarly retreat. One was the late Sir Walter Besant, the novelist, who told me before his death how much he enjoyed his life in Warwickshire, and his tenure as assistant master at Leamington College; the other was -- happily is, at the time of writing -- the Rev. Dr. Joseph Wood, the best headmaster the College ever had, who subsequently became the Principal of Harrow.

Walk down the boulevarde-like Parade now, where the fine shops rival those of London and Paris. Here you see Leamington life at its busiest and best -- gay, brightly dressed, active, ultra-modern; life ever-moving -- on foot, on horseback, in coach, in tramcar, taxi, motor car, carriage, and humble cab. The Parade is a pleasant decline as far as the Regent Hotel and the adjoining Town Hall -- an ideal promenade for the younger fashionables; and beyond, to the Jephson Gardens, Pump Room, and River Leam -- portions of the latter, though not from the Victoria Bridge, affording delightful views to lovers of the picturesque -it is almost as flat as a table; and this reach of Parade is obviously much appreciated by the many plump and pleasing and perhaps a little over-dressed fair dowagers, whom Hawthorne so felicitously describes in Our Old Home as he saw them then, during his sojourn in Leamington in the "'fifties".

Writing of Nathaniel Hawthorne reminds me that probably his kinsfolk from America, many of whom in the summer and autumn stay at Leamington in large numbers, may like to know the place where he resided when finishing his best novel, The Marble Faun. I write of this with the more pleasure because in the numerous descriptions of the town little or no mention is made of it, and I think the many admirers of this graceful descriptive novelist -- both English and American -- will find some delight in walking in his footsteps; and also because I live in his " nest of a place", as he called it, myself, and have done these thirteen years.

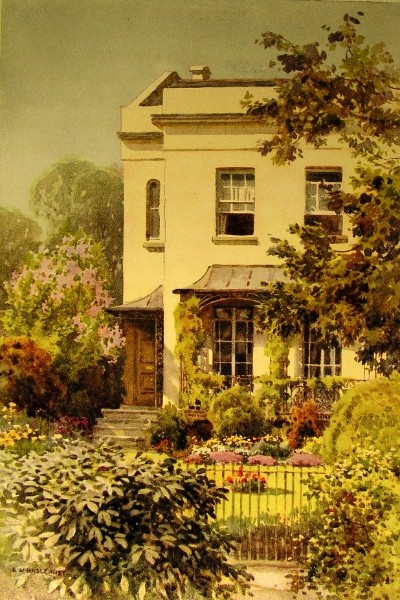

Nathaniel Hawthorne's House, Leamington

The way to Hawthorne's "nest of a place" is up the shady Holly Walk, which leads immediately out of the Royal Parade, in an easterly direction from the place where we are now standing, by the imposing Renaissance Town Hall and the attractive life-sized statue of Queen Victoria, which rises from the broad footway here -- the sole image in stone which the streets of the Royal Town at present reveal.

An umbrageous woodland walk right in the heart of an active and fashionable town is a glorious asset to it, and such is the Holly Walk at Leamington -- a walk so much loved by Hawthorne and by Dickens that the latter lays here the scene of Carker's first meeting with Edith Granger in Dombey and Son. This ancient walk is called Holly Walk because of the fine holly trees that used to grow here. Holly trees are here still -- small, newly-set trees, the older ones having disappeared; but the Walk is chiefly noted for its massive, centuries-old oaks, elms, and limes, in the topmost branches of which the rooks -- undisturbed by the flashings of the electric lights from the Theatre Royal in Regent Grove, which in the evenings illuminate that part of the Walk till it is as light as day -- build their annual rookery, adding just that one touch of rusticity which the urbanity of Leamington life requires to make it the Garden of mid-England.

On reaching the third section of the Holly Walk, for it is divided by roadways into three parts, near the Campion Hills -- from the summit of which, upon a clear day, the feudal towers of Warwick Castle can be distinctly seen -- the enquirer for Hawthorne's house -- you will have to enquire for it, for, like a jewel in the ocean cave, it is hidden from public view -- will ask for Lansdowne Circus, and, finding himself in that secluded arena of delightful tenements, that " nest of a place" so prettily described in Our Old Home, he will soon be in front of the veritable house which domiciled the celebrated author of The Scarlet Letter, The place will be immediately recognized from Hawthorne's description of it, for the Circus has not in the least changed since the novelist sojourned there, and his two children, Julian and Rose -- both, happily, at the time of writing, still living in New York -- played in the centre garden, where there are trees large enough for a forest.

Leaving this sylvan retreat on the edge of the world, passing the Holly Walk and going southward down the Willes Road, shaded by trees all the way, we come to the very heart of Leamington's beauty. Here is the softly-flowing Leam, meandering on to the village of Offchurch so slowly and happily that Hawthorne called it "the laziest little river in the world", not excepting even the Concord of America, upon the banks of which he passed so many pleasant years; and on the south side of it are the spacious Mill Gardens, and on the north the beautiful and ornamental landscape-like Jephson Gardens. Lean over the Willes Bridge here for a moment, upon each parapet east and west, and see the panorama of magnificent distances: delightful riverscapes -- the east backed by the Newbold Hills, clad in a blue haze; the west showing the imposing campanile of All Saints' Church, figuring up in the picture like the tower of a cathedral; the face of the river dotted here and there in the summer-time by a fleet of pleasure boats.

Enter the Jephson Gardens now by this eastern end, and go right through to the Parade, and to the Pump Room and Gardens across the Parade. These handsome Gardens take their title from the celebrated Dr. Jephson, who for many years was a resident of Leamington and made it his home, living in the elegant stone house at the corner of Dale Street called Beech Lawn -- making Leamington and himself famous at one and the same time.

Here, in these fair Gardens, is the very receptacle of Nature in the middle of a town -- a sanctuary for birds, an extended bed of roses in June, an ornamental lodge at each end, broad stretches of turf, sweet flower-bordered pathways, a lake with an island and a swannery, secluded glades, sloping woodland walks leading down to the river, a Corinthian temple with a statue therein of Dr. Jephson, and a quite Oriental bandstand with a glass-covered auditorium where high-class concerts are held in the summer months. There are but few places in England which can boast of so perfect a beauty-spot, so fair a haunt of the Muses. The town is indebted to the Willes family, of Newbold Comyn, an ancestral estate at the extreme eastern end of the Holly Walk, and especially to the late Edward Willes, to whose memory an obelisk is erected on the broad entrance way, for the possession of Gardens so beautiful, so well-ordered, and so happily placed in the heart of human life and activity.

The natural beauties of these Jephson Gardens, eye-delighting as they are, are not the only attractions to be found there. In the words of Byron,

|

Shakespeare says 't is silly, To gild refined gold or paint the lily; |

yet if the world's poet could only see this exquisite nook of greenery when illuminated with a thousand fairy lamps and Chinese lanterns, as it is during the summer evening promenade concerts held there, even he would say that the change was a striking and perhaps justifiable variation upon Nature's sublimer handiwork.

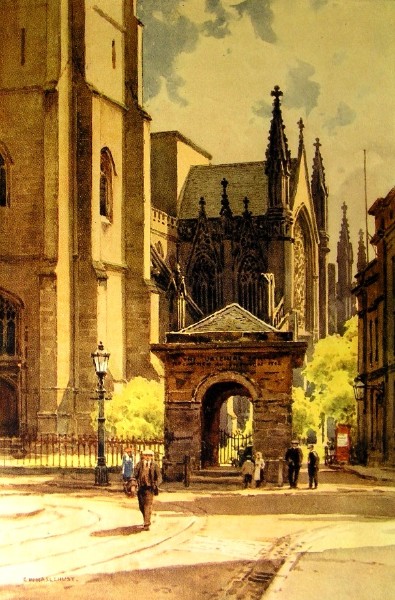

Crossing the gay Parade from the Jephson Gardens, just at its very gayest here, the Grand Pump Rooms and Baths, erected in 1813 at a cost of £30,000, and greatly enlarged and improved since, stand before us, with their imposing colonnade supported by Roman Doric pillars, their spacious gardens, with a picturesque kiosk for the band in the centre, and a shady avenue of lindens, extending from east to west, on the north. Though the former glory of the Pump Rooms, when Royalty and the fashionable world of England were wont to sip their morning glass of spa water here, may have departed, these baths are still some of the best equipped and most modern of any popular inland resort, quite equal, indeed, to those of Homburg, Spa, and Marienbad.

From the gardens of the Pump Rooms, where band concerts are held daily in summer, and where the atmosphere seems always afternoon, there is such an element of pleasure about it, a charming rustic bridge, called The York, after the King when Duke of York, spans the Leam. Passing over this you come to the ornate York Promenade, emerging beyond into the New River Walk -- as fine a stretch of embankment, extending for more than a mile to the western waterfall, tastefully laid out with flower-beds and shrubs, as you would look to find only in some gay Continental city; and upon the southern side of this picturesque River Walk is the extensive Victoria Park, with its bandstand, cycle track, and well-laid tennis-courts; for it must never be forgotten that Leamington is an ultra-modern town, where the ideal of life is pleasure, and tennis, archery, and golf -- played on splendid 18-hole links -- make up the sum of living.

Just at this point, then, Leamington is very beautiful, very leafy, very quiet and residential, and the spectator amid its scenes is often tempted to stay on the rest-a-while seats along the riverside, dreaming of life in a lotos-land, which, indeed, seems here -with a large cash balance at the bankers'. But we must now retrace our footsteps, or rather take a turn from the Victoria Park eastward, down the Avenue Road, into the busy town again; for though the Parish Church at Leamington may be the last scene to be described, it is by no manner of means the least -- Leamington being quite as religious as it is leafy.

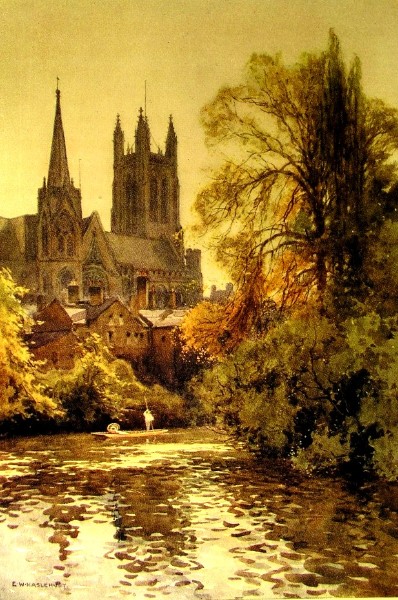

The best general view of the town, as I said at the beginning of this description, is that seen from the top of the Royal Parade, standing north and looking south. This scene is incomparable, and cannot be anywhere equalled for beauty and extending distance; but perhaps the most delightful way of looking upon the Church of All Saints is to see it first from Spencer Street, at the entrance to the town from the railway stations, both at its south end.

The Parade and Pump Room, Leamington

Seen from this view-point, the stranger to Leamington might be pardoned for thinking he was entering a cathedral city, for there, before him, at the foot of a short narrowish street, towers the tall and massive campanile of All Saints' Church, backgrounding the picture and giving him a vivid reminiscence of a similar scene at old-world Warwick. Just here, indeed, is the one point of resemblance between the sister towns. But upon turning the corner of the street and coming into the wide main artery of Leamington, leading from here right up to the northern top of the Parade, the illusion is quickly dispelled, since, though the church throws a chastened and religious glamour over the immediate scene, and conjures up visions of ages ago, but a few steps beyond is material life in its greatest, gayest, and brightest holiday attire, listening to the tuneful melodies of Mascagni's "Cavalleria Rusticana" issuing from the adjacent "Picture Palace".

As with the town of Leamington itself, so with its church -- change is writ large upon it everywhere. In those now ancient days when the Monks of Kenilworth were the possessors of the Manor of Leamington Priors, the Parish Church -- upon the site of which the present beautiful cathedral-like edifice, with its august campanile, now rears up its lofty top -- was a little village sanctuary, with a slanting roof and a short, peaked spire, which, at a later period, was replaced by a grey-stone square tower at the west end. Ecclesiastically speaking, it was not even a Parish Church, with the dignities and emoluments usually attached to such religious houses, but was simply a chapel-of-ease to the mother church of St. Peter's, then existing at the village of Wootton Wawen, in the heart of the Forest of Arden, to the priests of which the villagers of Leamington presumably had to pay tithes and other vicarial dues.

From this little rural church, however, piece by piece through the centuries, from a period anterior to the year 1230, has evolved the present ornate and striking edifice, which is a great asset to the town and the joy of all who behold it. The campanile, which dates from the year 1898, is a beautiful structure, richly carved, with saints in niches, and lighted at the base with stained-glass windows. It contains a peal of six bells -- originally four, but in the large extension of the church in 1825 the four bells were re-cast and a peal of six provided. Great interest attached to the re-casting of the four original bells, as it was firmly believed that they had held their position in the old wooden belfry, then dismantled, for upwards of two centuries. This conclusion was correctly arrived at from an inspection of the treble bell, which bore the date 1621 and a Latin inscription thus rendered: --

|

Come when I sound or it will show, To Church you never wish to go. |

Such, in brief, is the history of the Parish Church of Leamington.

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century many changes have taken place under successive vicars, until it is now one of the most noble and beautiful religious houses to be seen outside an ecclesiastical city. The nave and aisles of this elegant edifice are in the Perpendicular style of architecture, the transepts and chancel in the Decorated. There are some good specimens of stained glass in the interior, and a fine Rose Window, said to have been copied from one in the Cathedral of Rouen. Among the silver gilt communion plate is a handsome cup of Henry the Eighth's time. This is an artistic treasure 14 inches high, and richly embossed with figures. It bears the English hallmark of 1532, and originally belonged to the English chapel at Calais.

There are a few choice memorials to departed worthies to be found in the interior of All Saints', one of the most notable being the monument to Sir John Willes, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas; and among the gifts to the church the most attractive, perhaps, is the lovely reredos, sculptured with a replica of the fresco of "The Lord's Supper" by Leonardo da Vinci at Milan, presented by the late William Willes, of Newbold Comyn, to whose family Leamington owes so much. There are also three central windows filled with stained glass, erected to the memory of Diana, Frances, and Anna Maria, daughters of Charles Manners Sutton, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 to 1828, and through these the light falls dim and religious, imparting an air of deep reverence to this high-roofed, large-spaced, abbey-like sanctuary.

After all these fair scenes of the town have been looked over and examined, and the magic waters quaffed at the Camden Well-this is the antique-looking stone well-house near the church, originally built in 1803 by the lord of the manor? Heneage, fourth Earl of Aylesford -- or at the Royal Pump Room, there are the sylvan suburbs of Milverton and Lillington, which should be visited by every stranger, if only for the purpose of seeing the quite delightful rus-in-urbe character of leafy Leamington. Milverton is the West End of the town, and is now a part of it and inseparable from it; but Lillington in the northeast, though within the bounds of the fashionable spa, still retains all the charms of a secluded village far from the madding crowd.

The Old Well House, and Parish Church, Leamington

So from All Saints', which we now leave with a parting glance backward at the tower -- seen very artistically through the trees of Euston Place as you stand near the Regent Hotel and Town Hall-we move on, up the Parade now, and into the fine road leading to Kenilworth; and, taking Lillington Avenue, the third turn eastward, we come into the old way to the village, which, a century ago, was the only way through Leamington. And just here, standing like a sentinel on the east side of the highway, within sight of the ancient fourteenth-century church on the hill, is a large and wonderful, though now decaying, oak tree, which has a fame extending through the world. It is girt with iron palings, and has been known for at least eight centuries as "The Round Tree", marking the site of the middle of England; showing how clearly Warwickshire is the heart of England, and Leamington the heart of Warwickshire.

Probably Shakespeare rested beneath this ancient tree when on his historic tramp to London. This would be more than ever likely if the dramatist, as many think, journeyed through Wellesbourne, Warwick, and on to Rugby, because he would have to pass this tree on his way. No doubt, having regard to measurements, the tree has some very decided right to the title of standing upon the site of the centre of England, though there are other supposed centres in Warwickshire and Northants. The very great age and singular position of the tree -- growing right upon the roadside -- would also favour the assumption that it was used as one of the old Gospel Oaks under whose branches the Puritans of ages ago were wont to exhort sinners to repentance.

Called "The Round Tree" in Warwickshire and the neighbourhood from time immemorial, this ancient oak is an object of interest alike to the poet, painter, author, and mere sightseer. On the occasion of the jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887, the late Rev. Dr. Nicholson, then pastor of St. Alban's Church, Leamington, and a cultured Shakespeare scholar -- the man, indeed, who smashed the Cryptogram of Donnelly -- wrote an ode called "A Leaf from the Lillington Oak", of which one happy verse ran thus: --

|

You know the Midland oak, our Queen of trees, That lifts her branches bravely to the breeze? Deep from the parent root young scions grow, And round her feet I've seen the primrose blow. |

From this world-famed tree the stranger moves on to the quaint old church of Lillington, perched upon an elevation -- flat against the western sky. It is this which he is desirous of reaching, for surely, being so near to a fashion resort like Leamington, there are few prettier or more secluded scenes in the whole country. There are some very beautiful marble tombstones in the churchyard, entered by a lovely lichgate, and one or two spacious vaults; but these do not attract the attention half so much as a plain and dingy-looking stone on the east side of the chancel wall, not far from the interesting Leper's Squint, which is one of the features of the church. It is this which attracted the notice of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and to which he pathetically alludes in Our Old Home, evidently not knowing the plain English of it. The inscription upon the stone is quaint, simple, and brief, and is dated 1810:

|

I poorly lived, and poorly died, Poorly was buried, and no one cried. |

Whoever penned these lines must have been a sarcastic soul, for John Treen, the person in whose honour they were written, was really the old village miser -- a man of substance, indeed, who had no reason in the world either to have lived or died poor; and he certainly did not so die.

Lillington Church itself is one of those quiet, square-looking buildings, immured in greenwood, which seem to be distinctly the abode and home of religion, and which are well known in all the villages of Warwickshire. It is dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, and is so small as to be able to seat only some 415 worshippers. It is, however, full of interesting features and rich with stained glass. The tower is a fine embattled one of the fourteenth century, standing 14 feet high, and containing three bells -- the oldest one dating from 1625. The most ancient part of the church -- always religiously visited by American sightseers because of its associations with Hawthorne -- is the chancel, which presents relics of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to the eyes of lovers of the antique in ecclesiastical architecture. There is a fine Norman doorway -- blocked -- in the south wall. Near it is a now blocked opening, which, from its shape and size, proclaim it to have been a leperoscope, and a beautiful three-light window illustrating the text:

|

Hungered and ye gave me meat, Thirsty and ye gave me drink, A stranger and ye took me in, Naked and ye clothed me, Sick and ye visited me, In prison and ye came to me. |

With its enlarged and pretty churchyard and its own elevated position -- the dormer-window hole in the tower peering well over to the historic Castle of Warwick -- the sylvan church of Lillington is a scene of frequent resort, and should never be left out of the seeing by those in the heart of woody Warwickshire. It harmonized admirably with the rustic village -- not quite so rustic now, but nearly -- to which Hawthorne was so fond of wandering from his "nest of a place" at Leamington -- leaving one nest to enter another.

Such are a few of the charms and attractions of Warwick's young sister town. If leafy Leamington had no other claim upon the attention than its extreme prettiness, it would be entitled to permanent popularity. But it has other claims -- many others. It is clean, health-giving, well-ordered, within close range of all the admired shrines in Shakespeare's Country; and above all these it possesses in the teeming earth a medicine for the cure of poor humanity which eminent doctors say is superior to that to be found in numerous other spas of Europe. The wonder is that the public should migrate to foreign shores in quest of what they may find at home with perfect ease and in abundance, combined with such natural beauties and attractions of a literary and historic kind as are not often to be gathered in the provinces even of Beautiful England.

In conclusion, and as is natural in a town so very close to Stratford-on-Avon, which gave birth to the chief of geniuses, Leamington is in possession of a literary flavour of its own. Shakespeare, Addison, Shenstone, Scott, Landor, George Eliot, Ruskin, Hawthorne, Lytton, Sheridan Knowles, Dickens, Thackeray, Mortimer Collins, and the celebrated Madame Duclaux (née Mary Robinson), author of The Life of Renan and La Reine de Navarre, have all very interesting associations with Leamington, either by birth, residence, or sojourn. Dickens, indeed, must have stayed in the Royal Spa for some time, judging only from his characters in Dombey and Son. His Major Bagstock, the immortal "Joey B.", who was "sly, sir, devilish sly", and Mrs. Skewton were personages he drew from Leamington life, to mention only two.

The latter was taken from Mrs. Campbell, a well-known and justly honoured lady, who used to live at the corner house in York Terrace, exactly opposite the Clarendon Hotel, at the north end of the Royal Parade, one of whose daughters was the mother of the present Lady Fairfax -- Lucy of Charlecote Park -- Miss Campbell having married the late Henry Spencer Lucy. A jeweller, who formerly lived on the Parade at Leamington, and who had read Dombey and Son, used to describe Mrs. Campbell as being "laced up to the nines so tightly that before speaking she had to take hold of the counter-railing to recover her breath". He had so often spoken of her as "Mrs. Skewton" that one day, when she came into his shop, he fell into the grievous mistake of addressing her as such. "My name is not Skewton", was the indignant reply, upon which, of course, he could only offer the most profound apologies.

In the Jephson Gardens, Leamington

Dickens made his first public acquaintance with leafy Leamington in November, 1839. The royal spa was no doubt at its brightest period of good fortune in that year. The reputation of its magic waters was then at its highest, and the population was estimated to be 30,000 -- a portion of which might then aptly be called "floating" -- a number about as large as can be shown by the residential population of the three parishes of Leamington, Milverton, and Lillington at the present time. The fact of Leamington being a centre of fashion was evidently not overlooked by Charles Dickens, business man as well as novelist, and so in his English lecture tour of 1839 he made this garden town one of his chief calling-places.

He read passages from his Sketches by Boz before a large and cultured audience in the old Assembly Rooms, at the corner of Regent Street, and immediately opposite the gardens of the Regent Hotel. This one-time historical building, extending from the Parade to Bedford Street -- with its memories of the celebrated actress, Sarah Siddons (who often led off the dances at the fashionable ceremonies here with Mr. Bertie Greatheed of Guy's Cliffe), of Jack Mytton, the Marquis of Waterford, and other famous Corinthians of those stirring times -- has long since been demolished, and the abode of former pleasure has given place to a series of fine shops, providing for the domestic needs of present-day people -- especially for the needs of ladies. After nearly twenty years, in January, 1858, Dickens made his second and last appearance in Leamington. His fame was by that time completed and crowned, and still larger crowds flocked to do him honour.

The contemporary of Dickens, the author of the now classic Vanity Fair, must also be numbered among the literary celebrities who had more than a passing acquaintance with leafy Leamington. Dickens originated the lecture idea and Thackeray emulated it. He made his first and only public visit to the royal town in May, 1857, the year before the second appearance of his rival, " Boz ". The object of his coming was to deliver a lecture upon "The Life and Times of George the Third?), which he did, investing his address with that wealth of genuine humour, picturesque phraseology, and touching pathos for which he and his works were -- and are -- so justly noted.

It has never been suggested that Thackeray took, as Dickens did, any of the characters in his novels from Leamington life, though it is well known that he laid the scenes of his ever-green comedy, Boots at the Swan, in Copps's Royal Hotel -- a celebrated building, demolished in 1848 to admit the railway into Leamington, which extended over the whole space of ground in the High Street from the corner of Clemens Street to Court Street; but that two such eminent men of letters should have had even a flying association with this health-giving town on the banks of the leafy Leam is a fact which should not be forgotten by the future historian of English towns, who, if lacking in literary taste, may be addicted to passing over events which are of real and live interest in a century so absorbed in literature as the present twentieth.

For example, probably very few inhabitants of Leamington, or visitors thereto, at the present day -- so swift are the feet of time to outrun history -- are aware of the fact that in 1857 there was a genuine poet living in the town. Yet such was actually the case, and I mention it here because it is a fact of undeniable interest in the romance of literary Leamington. It must not be supposed that reference is made to Walter Savage Landor, or his equally poetic brother, Robert Eyres Landor, both of whom, being born at Elizabethan Warwick, have, naturally, very close associations with the Royal Spa. These poets did not actually reside in the town, as did that erratic son of Apollo who dared to address Tennyson, the late Poet Laureate, in the following language:

|

Who would care to pass his life away, Of the Lotos Land a dreamful denizen -- Lotos Islands in a waveless bay, Sung by Alfred Tennyson? Now and then a friend and some sauterne, Now and then a haunch of Highland venison; And for Lotos Lands I'll never yearn, Maugre Alfred Tennyson. |

These verses were written by Mortimer Collins in 1855, and two years later he took up his abode at leafy Leamington, and endeavoured to instruct the public mind from the columns of a periodical which he projected and edited. His journal, which bore the title, The Leamington Mercury, was, like himself, a little in advance of the times, and was the precursor of those so-called "Society" papers, now so popular, but which are really so injurious to the welfare of good morals and decorous living. It did not succeed, in a commercial sense, in the Royal Spa, in spite of the town being so fashionable, and, after a few brilliant months of life, The Leamington Mercury passed out of it, and Mortimer Collins, like Shakespeare before him, turned his footsteps to London -- the Mecca of the fortune-hunter. For him, as for "Stratford's wondrous son", this was doubtless the best thing he could have done, for in a short time he won a very considerable success in town as a poet and novelist. Others, too, of the literary genius have loved and lived at Leamington, or in close association with it; for example, Mrs. Kingsley, widow of the famous Charles Kingsley, and his daughters, Rose Kingsley and Mary St. Leger Harrison ("Lucas Malet"), who for many years were closely connected with the town, though they really lived in the sylvan village of Tachbrook Mallory, a little more than two miles from Leamington, and the home, in recent years, of the Landor family. I may also mention Sir Norman Lockyer, so eminent as an astronomer, who, though born at Rugby, took for his first wife a Leamington lady, was well known here in the "fifties", and was, for a time, assistant master in a school at historic Kenilworth.

Yet, probably, the picture which has pride of place in Leamington's literary gallery is that of Madame Duclaux, the celebrated Anglo-French poetess, and author, among other fine achievements already mentioned, of the monograph, Emily Bronte. Madame Duclaux has the additional merit of having been born at Leamington; and from her beautiful home in Paris she writes me, in felicitous language, of her happy girlhood, spent in Orleans House, Warwick Street, Leamington (next door to St. Alban's Church), and of her charming country house just outside the Shakespeare village of Rowington, near Warwick. Of the former she writes: "Orleans House is clear in my mind. My father had the ceilings painted by an Italian artist; we children admired them much, but loved the garden more, with its acacia trees and nightingales." Speaking of the house of her birth, she says: "I remember a lovely red Pyrus japonica in the garden, and the green curve of the road beyond our garden gate"; and of the Rowington dwelling: "I remember every field there, and the views from the house were very pretty. I think I can remember your house, too, from the photograph."

The literary associations of Leamington are, indeed, so fruitful of interest and amusement that a book might -- and ought -- to be written about them alone; but the brief notes I have mentioned in this description will serve to show that the town has a good claim to the title of "literary" as well as "leafy", and rightly so, as being the heart of fair and woody Warwickshire, from which sprang the greatest literary genius of the world.

copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2004

(Return to Web Text-ures)