| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XIII

JUST FISHING I have now decided that I will not live for the remainder of my days in the country between Okeechobee and the sea. I had thought it a place peculiarly fitted for the abode of mankind, but I have learned better. It is lacking in one product very necessary to the welfare of humanity; that is, a proper growth for fishing poles. Think of it! Hundreds of square miles of wilderness and not a fishing pole fit to be cut in the whole of it; and this with rivers that teem with fish that easily put the Maine lakes to the blush. The tree growth of the barrens and the savannas is pitch pine and palmetto. By the time the pitch pine is nine feet tall it has a trunk three inches in diameter, more or less. Even by cutting this and shaving it down you could not make a fishing pole. The palmetto is even more absurd. When a palmetto tree really starts from the ground its trunk is of its greatest diameter, say almost a foot. As the tree grows taller this remains about the same except that the “boots,” which are the bases of the clasping leaf stems, remain for a time, bracketing the tree all about with a sort of network trellis, which is ideal for all climbing things. After years these fall off and leave a clean, barkless trunk eight or ten inches in diameter and perhaps fifty feet tall. Where the growth is close some run much higher than this, and I have seen smooth, round, gray boles seventy or eighty feet from roots to feather-duster tops. As the tree grows older this trunk instead of enlarging grows thinner, wearing away with wind and weather, till the oldest trunks are but thin, gray bones that sometime get too frail to support the superstructure. Then comes a wind in the forest and the palmetto’s life work is finished. Fancy hunting in groves like that for a proper fishing pole! Bamboo, which makes — I acknowledge it grudgingly — about as good a pole as birch, may be planted here and will thrive, but few people have so far had the wisdom to set out bamboo groves. Lacking the culture of fishing poles by thus setting out bamboo the “Cracker” may indeed cut something which will serve in the hardwood swamps along the river banks. Here the maple will give him a heavy, stubby pole, which is better than none, or he may cut one from the soft, white growth of swamp ash. This is better. But the swamp ash seems to have a poor memory for direction. It starts out growing nobly toward the zenith, but by the second or third year it gets a new slant, say southwest. Next year this is changed, to southeast, then northeast, then west, all this while pushing diligently upward from the root. The result is that by the time a swamp ash is big enough to cut for a fishing pole, it turns at so many angles that it takes a very capable man to tell which side of the river he is on when he fishes with it. However, there is almost always someone in a Florida community who has a real bamboo pole, and as Florida people along the little rivers are the most kindly and generous of any I have ever met, it is not difficult to arrange the matter of the pole. The man who can find an angleworm in all Florida is an abler man than I am. The angleworm lives in loam In Florida the soil is made up of two ingredients, sharp sand and a peaty black substance which is decayed vegetable matter. Of just plain, honest loam there seems to be a sad lack. Hence the lack also of angleworms. Any such, trying to bore through the soil here, would be actually sandpapered out of existence. So the fisherman must turn to other sources for bait, and fortunately there is no lack. The straw bass, otherwise known as the large-mouthed black bass, is an inhabitant of North America. In the wilds of northern Canada, clear up on the sources of the Red River of the North, you will find him, and he occupies the fresh water stretches of the little rivers of southern Florida, as well. North or South he is most pleasantly edible, and most wonderfully prolific. In this region he grows to an ultimate weight of fifteen pounds, though that size is rare. Here, too, the straw bass provide both bait and fish. In the high waters of June they spawn in all the little sandy-bottomed “branches” that lead off the river, and by Christmas the young from a half inch to three inches in length fairly swarm in the shallow places near where they were spawned. More than this, the high water of September has carried their schools in countless millions high upon the savanna and when the winter brings drought these are stranded, collected in tiny pools everywhere. A scoop net and a pail are all you need. The cracker gets them with a piece of bagging roughly sewed on a barrel hoop. With this he scoops up the bottom of the pool, fish, mud, leaves, lizards and all else, sorting his needs from the agglomeration at his leisure by the pool side. After all with a pail full of such good bait, with a bamboo pole cheerfully borrowed, one is but a prig to regret angleworms and birch woods. To a man from the New England pastures, brought up on the good old pole and bait system of fishing, the dark pools of the lagoons that border the upper reaches of the St. Lucie are lull of mystery. When he drops the wriggling bait into their depths he little knows what he may pull up. The river itself has two currents even almost up to its source, one upstream, the other down. One comes from the reserve of rainfall in a thousand pools of the inland savanna, the other from the sea. Up with the full tide come sometimes the tarpon, rolling silvery bodies in the dark water till it gleams with moonlight reflections. Now and then a manatee, rare indeed nowadays, lifts a human-like face above its surface, then sinks again to browse on the weeds of the bottom. Here swims the black jewfish, never found under a hundred pounds in weight and running from that to five hundred. Up the river runs the cavalla, a mighty fighter that reaches a hundred pounds in weight and makes the most marvelous leaps when trying to escape the hook. Here in the depths or on the surface the alligator hunts, not at all particular as to what he gets to eat, provided he gets it. The alligator’s habit seems to be to masticate first and investigate at leisure.  “Up with the full tide come sometimes the tarpon, rolling silvery bodies in the dark water” All these things one may catch at one time or another when fishing in Florida rivers. Down on the Indian River the other day mullet fishermen found a manatee securely entangled in their net, hauled it ashore and photographed it, then released the frightened creature as the law requires. A cracker neighbor of mine down river who sets trawls gets all sorts of pleasant surprises when he goes to draw in his lines. The other morning he found the river full of a most extraordinary commotion, a veritable dragon hissing and roaring and lashing its brown water into foam. Several shots with a rifle quieted the beast, which turned out to be a six-foot alligator. A fish had swallowed the hook, then the alligator had swallowed the fish, sometime during the night, and had been keeping the river in uproar ever since, not because he had a hook in his stomach — an alligator will swallow hardware, stove wood, or anything else — but because he could not get away to meet an engagement elsewhere. Somewhat mindful of these things I sought for my first fishing spot a secluded bayou. Here I should be safe from dragons and here in the deep pools the bass congregate in the cool weather of late January. Here where the black water moves sedately along under the tender green of new willow leaves I drop my bait and watch my bob. In just such a spot fifteen hundred miles to the northward I have caught many a fish. Even the green of the willow is the same, nor is the willow itself of a strange variety. It is, I am confident, Salix nigra, the black willow or the brittle willow, easily recognized by various characteristics, one being the exceeding brittleness of its small twigs. The light sweep of a hand will bare a branch. Beyond the willow is the deep carnelian red of maple keys and there are young leaves on the soft-wooded swamp ash trees all about. Yet there is this difference. In the North the leaves on an ash tree come forward in stately march, in full company front, one twig no whit behind another. Here they are out of step, some twigs having just broken bud, others being clothed with half-grown leaves. Perpetual sunshine has made the ash unpunctual. With these things, however, all semblance to a Northern fishing pool ceases. I look past my floating bob into the depths and find there reflected the palms that top the wood with gray trunks and spreading frond-like leaves. The crooked ash shrubs hold air plants at every angle, each now sending up a stiff, rose-purple spike of bloom. On the opposite bank from the green willow grows a clump of the huge Achrostichum aureum, a Florida fern taller than myself, its tropic effect entirely dwarfing the Osmunda regalis and Osmunda cinnamomea, both of which line fishing pools North and seek the same locations down here. With these grow the linear leaves and white odorous blooms of the crinum, which is of the amaryllis family but whose blossoms have all the effect of a stalk of Easter lilies. These are springing into bloom all about, now, and soon the river will be lined with them. But what is this? The bob is most placidly and gently bobbing. Here is a bite almost like that of a Massachusetts eel. Something is taking the bait with an almost painful solemnity. It goes down a little and then a little more and finally I lift, inquiringly, and find a fish on the hook. It is a lively fish, too, once he feels the bite of the barb and struggles gamely but vainly as I lift him out. A bass! Only a little fellow, half to three-quarters of a pound, but who ever heard of a bass taking bait thus placidly? Up in a Massachusetts lake that I know the large-mouthed bass take a bait with a rush that carries everything before it. They whirl beneath the water and leap above it, shaking their heads to throw from the mouth the thing that hurts them. Surely Southern languor has gotten into the bones of the bass. Another comes to the hook in the same peaceful way and I land him. Then there is a lull. A wind out of the south blows up river and brings me the odor of palmetto blooms. I always think of loquats when I first smell this. It seems to be the same odor only not so strong, thinned out seemingly by distance. The palmetto blossom is not obtrusive. Its flower stalk springs from among the leaves and does not lift above them. The blooms are tiny and yellowish white. I speak of the loquat as having the same odor, but Southern people always say it reminds them of the Madeira vine. Following the odor of the palmetto blooms come two butterflies, both common to the North and the South, one a monarch, the other the tiger swallowtail, Papilio turnus. The turnus circles the pool and finally lights on the willow blooms across the stream. I watch him with some eagerness, for the blue of his after wings, instead of being confined to a single spot, is spread out into a cerulean border which is of singular beauty. All other markings are those of the turnus, but this is new to me, and while I am wondering whether this is merely an aberrant form or a variety of Papilio unknown to me, I feel a lively tugging at my line. I look down at the bob and laugh in glee. Here is an old friend I am confident. Only a sunfish bites thus with a bold bobbing that will not be denied. I pull him out and find I am right.

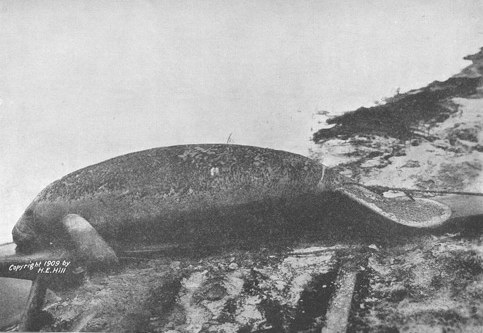

True indeed; the sunfish is no king of fishes, but his bite, compared with that of the Florida straw bass, is kingly indeed. And, as a matter of fact, properly pan broiled the sunfish of the Florida lagoons is the equal if not the superior to the lazy bass.  “A manatee, rare indeed nowadays.” The bass seem to occupy the depths of the pool, the sunfishes the shallower edges. These I soon fish out, but while I am doing it I happen to look at the center of the pool and see rise from below a fine big fish. My! but he must weigh five pounds. He sticks his nose just above the surface and scuttles below again. Him surely I must have. I sink deep and drop the bait low in the middle of the pool. Something bobs the float gently once or twice, then it sinks steadily and when I stop it I am sure the big fellow is on. I pull valiantly and so does he, but my muscle prevails and soon I swing him in onto the ground. This is a new fish to me, a well-built, fine-looking chap with a long back fin that nearly includes his tail. He certainly weighs several pounds and I am proud of him. I speculate as to his proper name, and finally conclude he must be a sea trout. Another bite in the deep hole and I swing to a good weight again. This time it is a three-pound catfish. Then there comes another lull. Nightfall comes rapidly when you are fishing. Before I know it the sky is crimsoning for the sunset and up and down the river the wood ducks begin to fly in flocks of three to ten crying plaintively, “Oo—eek, oo—eek.” My pool seems fished out and I begin to move on restlessly, trying new spots. In one of these I get a sudden rush of a bite, such as should come from a husky Northern bass and pull out a pickerel-like fish with scales like those of a snake and a long pointed snout set with bristling teeth. That is the last. I put him on the slender string with the others and plod along toward home in the crimson glory. Out of a drainage ditch I startle a half dozen killdeer plover and they dash madly away, screaming their lonely, querulous note. Every ditch has its killdeers and I suspect them of feeding on the young bass which I use for bait. By and by I am on the road again and as I pass a house set among pineapple and orange groves with its little patch of ladyfinger bananas behind it, some lively urchins cease their play to gaze rather critically at my string of fish “What do you call this one?” I ask, exhibiting my several pound “sea trout,” with carefully concealed pride. “That one?” comes the reply with undisguised scorn, “that's no good. That ‘s a mudfish. Some folks eat ‘em.” They all looked at me to see if I was of the “some folks” sort that would eat a mudfish and I hastened to disclaim any such intention. “Nobody eats catfish, either,” went on my informant. “And this one; what’s this?” I hazarded, exhibiting the long-snouted, piratical, pickerel-like one. “That’s a gar fish,” they replied in chorus, “that’s no good either.” As I went on up the road I heard them snickering among themselves, though they had been politely solemn to my face. “Huh,” said one. “He didn’t even know what a garfish was.” But then, like all the local fishermen they called the wide-mouthed bass trout. Knowledge is no one person’s monopoly, anyway. |