| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XIV

PALMETTOS OF THE ST. LUCIE The cattle men, whose wealth is in range cattle, roaming at will, take advantage of the dry weather of winter to set the world afire. Hence a soft, blue haze all about that makes the wide spaces between trees misty and uncertain and puts vague touches of romance on all distances. By day a cloudy pillar shows where this fire has got into thick, young growths of pines and is towering heavenward in pitchy smoke. By night the level distance is weird with flickering light, and the wanderer is guided by a moving column of flame as were the Israelites of old. After these moving lines of fire have passed, the flame often lingers for days in stumps of the pine, eating away at the fat wood which is solid and green with resin. A chip off a dead stump of a Florida pine will burn at the touch of a match. All over the flatwoods are these stumps, often standing fifty feet high and a foot or two in diameter. The bark has fallen, leaving them to personate thin ghosts in the vivid light of moon-flooded nights. The sap wood of these trees softens with decay after a while, but the heart stands firm for unlimited years. The Florida farmers, who must fence their farms from the range cattle if they wish to keep them, use this heartwood for fence posts and it is fabled to last in the ground a century. When the fires of the cattle men have burned over the ground, leaving nothing behind but ashes and the blackened trunks of scrub palmettos which look like scaly dragons, charred and writhing because of the fire, the sap wood of the standing pine trunks holds the flame and it winds spirally about the hard center night after night, till it flutters like a bird from the topmost pinnacle and vanishes toward the stars. Of windy nights you may see these crimson flocks fluttering and taking wing. By day the black heart wood of the stub still stands, charred, but erect and firm as ever.

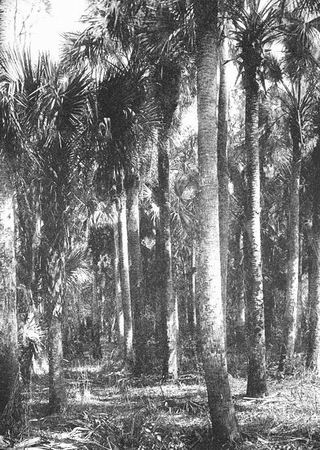

Very different is it with

the sabal palmettos whose cabbage heads tower often as high as the

pines, but whose roots are in the moister soil. The fire may run up

these if they have not lost the “boots” as the clasping petioles of

their great leaves are called, but it does nothing more than slightly

blacken the real trunk. The palmetto decays differently from the pine.

When it lies rotting in the forest it is the outer husk which is solid

after years; the inner part decays and leaves a hollow which is an easy

refuge for wild things. In the palmetto trunk the coon finds safety and

the opossum curls up by day, waiting for his nightly raiding time to

come. The cotton-tailed rabbit, however, does not affect the interior

of the palmetto stub. For a siesta after foraging he tramps out a

little grassy apartment among the scrub palmettos. Usually this is

entered by the top, the rabbit hopping down into it when arriving and

hopping out with nervous haste and white tail high in air when I happen

upon him.  "Sabal palmettos whose cabbage heads tower often as high as the pines" When he comes to hollow palmetto logs, I suspect br’er rabbit of passing with a shudder, not because of opossums or raccoons, or foxes or polecats, all of which might rush out on him from such places, and all of which eat him. But the rabbit has little real fear of these. He can escape from them too readily. There is another occasional occupant of the hollow palmetto, however, for whom br’er rabbit has much horror, and I confess to similar feelings when I chance upon him suddenly. That is the gopher snake. Not that I have any real excuse for this feeling, for the gopher snake is not only perfectly harmless to all creatures except those that he swallows whole, but he is one of the handsomest snakes known. His main color is an intense indigo blue, so deep that it is a blue black, whence another common name, the indigo snake. His entire scalation is as polished as glass and his length reaches sometimes nine feet. One that I know lives by the roadside down near the river and I can find him there almost any sunny day that I go along. He cast his skin some days ago and came out the most striking snake I have ever seen. His blue-black back shone like glass, his under parts showed all the prismatic colors on the plates of the abdomen, where he looked like burnished metal, while his chin, throat and two streaks on each side of the head were a rich red. The road near his favorite sunning spot has been corduroyed with palmetto trunks, and when I approach too near, say within two or three feet, he slips forward with an easy, gliding motion and goes into a hollow trunk, usually turning round within and putting a foot or two of his head and neck out again to see what is going on. He is not at all afraid and shows neither nervousness nor anger as he glides away. In fact, I am the one that is nervous. I am convinced that Adam was my ancestor. It was Eve that hobnobbed with the serpent I can see Adam having cold chills and stepping lively for a big stick. The gopher is really in a limited way a household pet of the region. He is a mighty hunter of rats, and in consequence is welcomed about barns and outbuildings and even sometimes invades the loosely built houses in his vocation. He yields readily to friendly advances and in captivity is a gentle pet. To really see palmettos you wilt do well to explore the St. Lucie River. Incidentally you wilt see a river whose tropical beauty exceeds that of the famed Tomoka, and, I believe, any other river in. Florida. I think the St. Lucie originally intended to be straightforward, but it does it by a most amazing series of windings and crooks. Within a half-mile you will face all points of the compass on this bewildering, bewitching river, nor may you be sure by the current which way you are going. So slight is the fall between source and mouth that the salt sea which floods in through the Indian River gets tangled in the crooks of the St. Lucie and goes on and on to within a few miles of the source before its force is entirely spent. Then only does it allow the water from the savanna springs to go downward to the sea. Twenty miles up come the mangroves, their seeds floating on the brimming tides and germinating within the husk, to find root eventually along the shores and grow new shrubs with ovate, shiny leaves. At high tide the mangroves remind me of the alders which fringe the ponds and streams at home. At low tide to see them from the river is to be astonished at their forests of inch-thick water-pipe roots, dropping in parallel lines, perpendicularly from their butts into the brackish water Higher than the mangroves grow the soft, swamp ash trees, holding the ground in the river-carved swamps sometimes to the seclusion of other trees. The wood of these trees is very soft, white and brittle and the trunks are never large, six inches being a good diameter. Soon, too, they become hollow and the crooked, leaning trees rot and fall to the ground bringing with them great stores of air plants that grow, pineapple-like, along their trunks from base to tip. With the tender green of the young ash leaves come the blossoms of these air plants, giving the angular, awkward trees the appearance of putting out tropic spikes of purple-stemmed, blue~ flowered beauty. Here and there the live-oaks, never very numerous in this region, show dark green on the higher banks. The live-oak is the symbol of stability and even virility, if you please, but it is at the best somber and glum. It drops its leaves grudgingly, one by one, putting out its new ones in the same way, thus always retaining its cloth of dark green. In October it was hard to distinguish the difference between the live-oaks and the water-oaks. Both seemed somber and dour. Not long ago the water-oaks went bare in evidence that winter was here. But now you should see them! First they showed a misty, sage green with tender lights in it. The sun of another day lighted this up with a nascent bronze that was full of soft withdrawals and tender shynesses, and the wee leaves grew hourly broader with a surgence of gentle green through the short petioles, suffusing the whole tree with a tender, translucent beauty, as endearing as that of a Massachusetts May. Here in southern Florida winter is but a word that is not quite spoken, but spring comes very really, though not as it does in the North. There it rises like an all-pervading tide. Here it wells forth in spots as if the fountain Ponce de Leon sought bubbled at intervals, here and there. Spring in the North is a symphony; here it is a fugue. Along the St. Lucie grow maples all richly salmon red with young leaves and winged fruit. Willows are gray-green, too, and the sweet gum is a milky way of green stars with the divergent points of its new leaves. Here are creepers, lithe as snakes that climb from the muddy shores to the tops of the highest trees and swing down again, trailing tips in the water. In the dusk of the swamps the white blooms of the crinum glow like stars that are reflected in the black water. But with all this luxuriance of other growing things the tree that dominates the St Lucie is the palmetto. It grows from the black muck of the swamp, where the slow tides swirl sedately around its roots, and it towers from the highest bank where the live-oak roots grip the sand with tenacity that holds it even against the undermining effect of the spring floods. Where the floods have had their way it leans far out over the water, or even drops into it, the long, straight trunk a famous climbing place for foot-wide turtles that come out to sun themselves and sit in solemn, silent rows with their heads tipped back so that the warmth may strike their throats. These plunge beneath the surface with much splashing as you pass, then secretly and silently paddle back and crawl out after a while. If the current did not cut the banks and let the palmettos fall the big turtles would have hard work to get their share of the spring sunshine. Often a water-oak leans far out over the water in this way, a favorite roosting place for the water turkeys. The water turkey reminds me of a crow that has had his neck pulled. He is rather rare, of a not very numerous family, the anhingidae or darters, there being only four species in the world. The bird is the funniest thing on the river. Its glossy crow-black is touched with white, and in some specimens this change begins at the shoulders and makes the whole neck look as if plucked. The anhinga dives like a loon and lives on fish, though how it gets them down that preposterously thin neck I cannot explain. It is sometimes called snake-bird, and perhaps the neck stretches for deglutition as does a snake’s. Often as I paddle up to one, pointing his slim, serrate-toothed, sharp-pointed bill this way and that, as if trying to poke holes in the atmosphere through which to escape, then with a tremendous burst of nervous energy whirring on short wings over my head, I note a big bunch at the base of this preposterous neck, which I take to be his crop distended with nourishing fish. He is a nervous bird, and he seems to fly with a lump in his throat. Once in the air he soars prettily like a hawk, and often comes back into his tree again, slamming with scrambling haste to a perch whence he cranes his head this way and that. Sometimes the water turkey, surprised on a low limb, will go into the river with a splash that reminds me of the way a kingfisher takes a fish. After that it is hard to see the bird again. He has a way of coming just to the surface and poking up that slim head and neck to look around while yet his body is submerged. If you do happen to see him you then realize why the name “snake-bird” has been given to him. The natives who refuse to eat the catfish from the river declare the water turkey most toothsome. After all, there is a good deal in a name. No one eats cats, but we all know turkey is delicious. The pileated woodpeckers love the banks of the St. Lucie, their homes in the holes that so often look toward the river from palmetto stubs on the banks. Once seen, I do not find the bird difficult of approach. I watched one at close range the other morning for a quarter of an hour while he dug at an ash limb as if he intended to make a nest in it, but after all his grubbing was merely for breakfast food, which he pulled out and swallowed with gusto, his little slim neck and perky bead reminding me of those of a guinea-fowl. I do not think Ceophoeus pileatus a handsome bird, but he is fast becoming a rare one and just to watch a pair is a privilege. There is nothing rare about the little green heron. He is almost as common to Massachusetts in summer as he is to Florida in winter, yet I think I would pick him for the gentle genius of the stream. On bright days this little fellow is not so easy to find. You will pass a dozen, sitting motionless and dumpy, head on breast and neck telescoped down between the shoulders, for one that you will see. He is a sweet little cherub of a bird thus, and he will keep his pose till you approach very near, knowing that immobility often means invisibility. I like to steadily intrude on him and watch his change of demeanor when he feels sure that he is watched. Gradually all dumpiness goes. His neck appears, then stretches till he will almost rival the water turkey. Alertness grows upon him. His head cocks with a perky air and a crest rises on it. He walks, foot over foot, up his limb and finally poises there, as assertive and vigilant as a red-headed Street urchin standing tiptoe behind the bat when the bases are full and the honor of the ward hangs on the next play. He reminds me of just that. But the resemblance ceases when he flies, for he just gives a flop or two, over perhaps to the next bush, then sinks into immobility again, seemingly confident that he has found safety by his flop.

But over all rare or common

birds, graceful or awkward shrubs or trees, waves everywhere the

benedictory grace of the palmettos. Ferns love them and climb by the

brackets of their young trunks to the tops where they still grow when

the trees are old and the boles are smooth to the crown of living

petioles. Often the weather or some strange trick of growth has caned

the upper portions of these aged trunks till the feathery fronds seem

set in vases mounted in pedestals, and the ferns and air plants seem as

if tucked into these by the slim fingers of some tall goddess of the

woods. So across them falls the topaz splendor of the tropic sunset and

as quick night glooms the river the passing sun caresses the palmettos

last and leaves them, rustling gentle wildwood talk among themselves,

waiting his return. |