| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

V A SNOWSTORM Margaret grew steadily stronger. She was

out of doors

a great deal, rambling about in the mornings on the hard snow; and

later in the

day, when the snow became soft, she would play on the piazza, or talk

with

Beechnut while he was at his work. The weather was all the time getting

warmer,

and the snow was fast disappearing. One day Margaret found some little

green

leaves beside a walk in the yard. Beechnut came by as she was looking

at them,

and she asked him how much longer he thought the snow would last. "I don't know," replied Beechnut. "We

may have more before this is gone. In fact, I think it looks as if

there might

be a snowstorm gathering now." Margaret turned her eyes toward the sky

and saw that

it was hazy, especially toward the south. The sunshine was gradually

becoming

dimmer, and within half an hour the air grew so cold that Margaret went

into

the house. The sky was gray, and darkness came that night much earlier

than

usual. When the children went upstairs to go to bed the storm had

begun.

Margaret looked out of a window. "0 dear me!" she exclaimed,

"the garden is covered deep with snow again. The flowers will all be

killed." "No," said Frank, "they don't care for

the snow. I'm glad to have such a storm. We shall have a good time

going to

break out the roads." "Shall we?" said Margaret. "Yes," was Frank's response, "if we

have snow and drifts enough. I hope it will snow all night, and blow —

oh, how

I hope it will blow!" It did snow all night, and in the morning, when

Margaret awoke, the snow was piled up against the windows so that she

could

scarcely see out of them. As soon as she was dressed she went

downstairs and

found Frank in the sitting room. They both looked out of the window a

few

minutes, and then Margaret sat down on a low stool by the fireplace and

began

to play with Carlo. Tom was asleep on the other side of the hearth. "Oh, Margaret," said Frank, "come here

and see the drops run down on the glass." "I have seen them already," replied

Margaret, "and I know what makes them run down." "What is it?" asked Frank. "Why," said she, "it is because the,

glass is warm and melts the snowflakes that strike against it outside."

Margaret had received this explanation

from her aunt

before she came downstairs. Frank put his hand on the glass. "It is not

warm," said he. "It is cold." "No," said Margaret, "it is warm. My

aunt told me it was warm, and she knows." "But come and feel it yourself," urged

Frank, "it is as cold as ice." "I don't wish to feel it," said Margaret.

"I know it is warm because my aunt says it is." Frank then left the window and went toward

Margaret

saying, "Just come and feel;" and he took hold of her arm to pull her

along. At this instant the door opened and

Beechnut came in

bringing an armful of wood for the fire. "What's the matter?" he

inquired. "Frank won't leave me alone," replied

Margaret. "She says the glass of the window is

warm,"

explained Frank, "and I want her to feel it." "One of you says it is warm, and the other

says

it is cold; is that it?" asked Beechnut. "Yes," Frank answered. "I'll go and see," said Beechnut. So he laid down his wood and then he put

his hand in

his pocket and took out a mitten. "What are you going to do?" asked Frank. "I am going to put this mitten on in case

the

glass should be so hot as to burn me," Beechnut replied. He advanced very cautiously toward the

window,

reaching his hand out as if he were afraid he might get burned. In

fact, he

mimicked so perfectly the appearance of a boy about to touch hot iron

that

Frank and Margaret forgot their dispute and went to see what he would

do. Beechnut put his hand on the window, and

the instant

he touched it he caught his hand away, crying out, "Oh, how hot!"

Then he added, "I believe I'll try it without my mitten." So saying, he drew off his mitten and

touched his bare

hand to the glass. Immediately he jumped as if he had been burned, and

began to

caper about the room shaking and blowing his fingers and making such

droll

faces of distress that Frank and Margaret filled the room with shouts

of

laughter. Beechnut danced and hopped along to the door, opened it, and

disappeared. But the instant he passed out he resumed his ordinary

appearance

and walked just as if nothing had happened, in the soberest manner

possible,

through the kitchen past Mrs. Henley who was busy there preparing

breakfast. Margaret followed Beechnut and found him

in the shed

taking down more wood from a pile. "Was it really hot, Beechnut?" she

asked. "Ah," responded Beechnut, shaking his

head,

"if you could only see my

fingers — all blistered!"  "But was it hot, really?" said Margaret.

"Tell me." "Well," said Beechnut, "you and Frank

come here into the shed, after breakfast, and I'll settle t h e dispute

for

you." Margaret assented to this and went in and

told Frank.

She found him relating the story of the dispute to Wallace who had just

come

downstairs. Wallace put his hand on the glass and said, "Certainly the

glass is not so warm as the hand, and it therefore feels cold when we

touch it;

but it is warmer than the snow, and as a result the snow that gets

against it

is melted." "But it is cold when we feel it," said

Frank. "Yes," Wallace agreed, "or rather it feels cold to the

hand." "There!" exclaimed Frank, turning to

Margaret. "I told you so." "I am not going to talk about it any

more,"

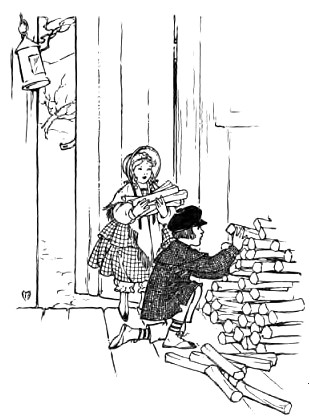

said Margaret. "Beechnut says he will settle it after breakfast." When they had eaten, Margaret put on her

bonnet and

shawl, and she and Frank went to the shed. Beechnut was piling wood.

The doors

of the shed were all shut to keep out the storm, which was beating

incessantly

against the building as if the wind and snow were trying to get in.

Some of the

snow had been driven through the crack beneath one of the doors and lay

there

in a little drift. Frank and Margaret made snowballs from it and then

went to

Beechnut to get their dispute settled. "I'll read the law about disputes out of

the

Code Antonio," said Beechnut. The emperor Napoleon caused a body of laws

to be

framed which became very celebrated all over the world, and was called

the Code

Napoleon. It was in imitation of this name that Beechnut called the

laws which

he announced from time to time to Frank and Margaret the Code Antonio. He put his hand in one of his coat

pockets, took out

a small book, and after turning the leaves began to read. "Chapter

forty-eight.

Of Disputes. Section First. If two brothers get into a dispute it is

the older

that is in the wrong; for he ought to be the wiser, and disputing among

children is folly." "But we are not two brothers," said

Margaret. "Section Second," continued Beechnut,

still

looking on his book. "If a brother and a sister get into a dispute it

is

the brother who is in the wrong, for he ought to be too polite to

dispute with

a lady." "But we are not a brother and sister,"

said

Margaret. "It comes pretty near it," commented

Beechnut, shutting the book. "Let me see your book," said Frank as Beechnut was putting it in his pocket.  "No; but I'll tell you what I will do,"

was

Beechnut's response. "Yes, tell us," said Frank. "If you and Margaret will pile wood for me

one

hour, I'll tap some maple trees for you." "When will you tap them?" Frank

questioned. "The first good day," replied Beechnut.

"Well, Margaret," said Frank, "let's do it." Margaret

assented, and the children worked for an hour piling wood very

industriously. Beechnut always adopted much this same

mode whenever

he attempted to settle a dispute between Frank and Margaret. He amused

them at

first by some original device to excite their interest and

curiosity, or to

make them laugh, and then contrived to turn their attention off from

the

subject of dispute into a wholly new channel. That afternoon, when Frank's lesson hour

was over, he

came down into the sitting room to play with Margaret. The snow still

continued

to fall, and the two children saw that it was getting very deep in the

yard.

The garden gate was entirely covered by a great drift. Frank presently

sat down

beside the fire to teach his dog Tom to "speak," as he called it. He

held a piece of bread up above the dog's reach and tried to make him

bark for

it by saying, "Speak, Tommy, speak!" Tom would seem very anxious and uneasy,

and would

whine and make all sorts of disagreeable noises and finally bark. As

soon as he

barked Frank would give him the bread, and then, breaking another piece

from a

slice he had in his lap, he would start the same lesson again. While he

was

engaged in this manner, Beechnut passed through the room, but paused to

ask

Frank what he was doing with his dog. "I am teaching him to speak," replied

Frank, and he broke off another small piece of bread, held it up high,

and said

as before, "Speak, Tommy, speak!" Tommy wiggled and jumped about and whined,

but being

perhaps a little disturbed by the presence of Beechnut would not bark. "He would speak a minute or two ago,"

Frank

declared. "I am glad he won't now," said Beechnut. "Why? Don't you think it is a good plan to

teach

him something?" asked Frank. "Yes," Beechnut replied; "but I should

teach him something useful, and not disagreeable tricks." "What would you teach him?" Frank

inquired. "Oh, I don't know," said Beechnut. "

Perhaps I should teach him to draw like a horse. If you teach both the

dogs to

draw, they might help you get your sap to the boiling kettle when you

make

sugar." Beechnut now left the room on his way to

the barn.

Frank was very much pleased with the idea of teaching the dogs to draw,

and

after talking with Margaret about it a few minutes he concluded to go

out and

ask Beechnut how it was to be done. He found him in the barn leading

out the horse

from its stall. "Where are you going?" asked Frank.

"To the post office," replied Beechnut. "Ho!" said Frank,

"that is in the village, a mile away. You can't get there." "I can try," Beechnut responded, and he

put

a folded blanket on the horse's back and fastened it on with a long

strap. Then

he mounted. "Aren't you going to have a bridle?" Frank

questioned. "No," said Beechnut, "a halter is

bridle enough for me when I have the Marshal to ride." The Marshal was very handsome and very

spirited, but

so well trained that Beechnut could control him by a halter as well as

by a

bridle. "Before you go," said Frank, "I wish

you would show us how to teach our dogs to draw, and make us a

harness." "No," responded Beechnut, "it would

take me half an hour to do that." "And how long will it be before you get

back

from the post office?" asked Frank. "It will take me at least an hour to go

and

come," said Beechnut, " if the drifts are as deep as I suppose." "I mean to go and ask Wallace to ride to

the

post office," said Frank, "and then you can stay and help us." "Very well; but tell him it is your plan

and not

mine," rejoined Beechnut. Frank ran into the house and soon came

back

accompanied by Wallace, who had a cap on his head, and his coat

buttoned up to

his chin. "I am afraid you will find it very hard

getting

to the post office, Mr. Wallace," said Beechnut. "I expect to find the roads blocked," Wallace responded; "but I would like to go very much, notwithstanding — only I believe you must give me a saddle and bridle."  Beechnut dismounted, saddled and bridled

the horse

and delivered him to Wallace. He then opened one half of the great barn

door,

and Wallace sallied forth into the snow. Beechnut and Frank stood

watching him.

The wind howled among the tops of the trees, all traces of the road had

disappeared from view, and even the tops of the fences were in many

places

covered. Beyond the road the whole landscape was concealed by the

falling

flakes that were driven furiously by the force of the gale. As the Marshal advanced through the yard

the snow was

so deep that he could scarcely wallow through it. When he approached

the

gateway Wallace found that the whole line of the fence at that point,

gateway

and all, was entirely hidden by a monstrous drift. The horse pushed

into this

drift, the snow growing deeper and deeper at every step. When at length

it came

up to his shoulders he could go no farther. He struggled a moment and

stopped. Wallace then got off his back, and leaving

him went

on ahead trampling the snow down with his feet and attempting to break

a way

through the drift. He advanced very slowly, but finally succeeded in

getting

through the deepest of the snow and then turned to the horse, which had

followed close behind. "Now, old fellow," said he, "I think you

can carry me once more." He mounted, and the horse plodded on until

the flying

flakes concealed him from the sight of Beechnut and Frank who had

continued to

watch from the barn door. "I wish I had asked Wallace to let me go

too,

riding behind him," said Frank. Beechnut did not reply, but shut the barn

door, and

then he and Frank went into the house to begin teaching the dogs to

draw.

First, Beechnut made the harness. Each harness consisted of a collar of

soft

leather and two long straps, one on either side, to serve for traces.

They used

Beechnut's drag for a cart and only hitched up one dog at a time. Carlo

learned

the faster; but before Wallace returned, either of the dogs would go

very well

across the room drawing the drag after him. Beechnut said that Frank and Margaret must

teach them

more every day, and thus by the time the snow hardened so that they

could

commence the sap boiling, the dogs would make a very good team. He then

went

away. Frank was tired of training the dogs, and

he said he

would go and cut some stems of elder bushes to make sap spouts.

Margaret told

him the snow was too deep, but Frank thought not. So he put on his

boots, and

with a pair of leather straps fastened his trousers down about his

ankles to

prevent the snow from getting up under them. He then went out on the

piazza

which led to the yard behind the house, while Margaret stood at the

window to

see. He waded along through the yard, looking

around

continually toward Margaret and tumbling down purposely into the snow

to make

her laugh, and wallowing about here and there wherever the snow was

deepest.

But, as he advanced in the direction he had to go to reach the elder

bushes, he

found the snow so deep that he could not get along. It came up to his

waist. He

turned toward Margaret and stood still, laughing. Suddenly, he pointed

at

something out among the trees of the garden. Margaret pushed up the window a little and

asked,

"What is it?" "Snowbirds," Frank called back. Margaret put the window down to keep out

the

blustering storm, and Frank waded forth from the drift and came toward

the

house. As soon as he got to the piazza he began to stamp about its

floor,

shaking and brushing the snow off his clothes. He then went to the

window where

Margaret was and shouted that he was going to get the snowshoes. Off he went to the shed and soon returned

with the

snowshoes on his feet. He started again to go to the elder bushes, but

though

he no longer sank in the snow, the shoes were so large that it was

extremely

difficult for him to manage them. He staggered on very awkwardly, and

Margaret

watched him until he passed around the corner of the house. Then her

attention

was attracted in another direction, for Wallace was coming in from the

post

office, whitened from head to foot. |