| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

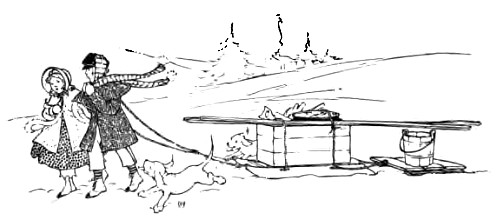

VI SUGAR MAKING It was nearly a week before the snow which

fell in

the great storm had become so solid that Frank and Margaret could walk

on it.

By then Carlo and Tom were well trained to draw, and in order to be

sure that

they could draw a load of sap, Frank practiced them in the yard drawing

a pail

of water. The pail was of tin, and it had a cover to keep the water

from

spilling. Beechnut said the trees they were to tap

were on the

bank of the river not far away, just above where a brook emptied into

it. He

tapped six of them the day before the children were to go down, and he

gave

particular directions as to what they were to do in collecting and

boiling the

sap. Frank was to draw down all the things that

were

necessary on one of his hand sleds. He did not let the dogs draw them,

for he

wished to save their strength, as he said, for the sap. First he put on

the

sled a large box which was to hold the things going down, and to be

turned bottom

upward and serve for a table when on the spot. Into this box he put a

kettle, a

number of sticks of wood, a short iron chain, and a small saw. The saw

was to

cut up for fuel dead branches of trees and other wood such as they

might find

along the river. In the kettle were some pieces of kindling

wood, and

a small box of matches. To the top of the box, after the other things

had been

put in, he tied three poles about six feet long. The drag was attached

by its

rope to the back of the hand sled that it might be taken along at the

same

time. In the bottom of the tin pail was a paper with some slices of

bread and

four oranges tied up in it, and accompanying this parcel were two

saucers and

two spoons. These spoons and saucers the children

intended to use

in trying the sap from time to time, as the boiling went on, to see

whether it

was growing sweeter. When all was ready the whole party set off

from the

house, with Carlo and Tom running before the sled and frisking about in

great

glee. "Ah," said Frank, "you dogs little know the hard work you

have got to do to-day hauling sap." The children crossed the brook by a bridge

a short

distance from its mouth. They did not need to use the bridge, for the

stream

was frozen over quite solid, but a pathway led across it and down to

the beach

where they planned to build their fire. The ground on the beach was

nearly

bare, most of the snow having been blown off by the wind. Margaret and

Frank

easily found a protected spot, where they could have their fire, on the

smooth

and dry surface of the sand. Frank stopped with his sled when he

reached this spot

and said, "While I am building the fire, Margaret, you can be putting

the

harnesses on the dogs." He at once began preparations for the

fire, and

Margaret took one of the harnesses from the drag and called to Carlo.

But Carlo

saw the harness in her hand, and as he knew very well what it meant he

would

not come. Margaret went toward him to catch him, and he bounded away

from her

and ran out on the river. "Oh, dear me!" Margaret exclaimed,

"what shall I do?" "Never mind," said Frank, "I'll catch

him for you by and by." So Margaret sat down in the shelter of the

bank, on a

seat Beechnut had made there in the summer, and watched Frank build the

fire.

He had taken the three poles from the sled, set them up so they formed

a sort

of tripod, and tied the tops together. Then he fastened the chain to

the poles

where they joined, letting one end with a hook attached hang down half

way to

the ground. "There!" said he to Margaret, "when I

put the kettle on the hook, it will be just far enough above the fire."

He selected the two largest sticks he had

brought,

placed them parallel to each other under the tripod and laid kindlings

between

them, and the rest of the sticks across them. Finally, he hung the

kettle on

the hook, and then he said, "Now we will go and get the sap." It was not without considerable difficulty

that he

caught the dogs. They both preferred running about on such a pleasant

morning,

rather than being harnessed to a drag and compelled to draw a heavy

load.

Frank, however, with Margaret's assistance, succeeded at last in

catching them

and harnessing them to the drag. That done, he and Margaret set out

after the

sap. They went along the river, following the shore up a little way,

and very

soon came to the trees Beechnut had tapped for them. To their great delight they found the

dishes almost

full of sap, and they lifted each in turn carefully and emptied it into

the

pail. When they finished they put the cover on the pail and started to

return.

The dogs pulled well and took the load along in a very satisfactory

manner. As soon as they arrived at the camp they poured the sap into the kettle and Frank lighted the fire. Next they unharnessed the dogs and set them free, and then taking the hand sled and the saw they went along the banks to get a load of wood. Frank sawed off the dead and dry branches of the trees, and Margaret put them on the sled.  With this wood they kept the fire burning

finely for

some hours until almost all the water of the sap was boiled away, and

what

remained became a thick sweet syrup. They kept tasting from the kettle

during

the boiling process, taking out a little in their spoons and cooling it

in

their saucers. Finally they concluded to put some on their bread, and

they

found it very nice. In fact, the sweeter and thicker the contents of

the kettle

became the more they ate, until, at last, Frank, who had gone to the

kettle for

a fresh supply, said in a tone of great despondency, "Why, Margaret!

our

maple syrup is almost eaten up." Margaret herself looked in, and it was

plain that

what Frank had said was true. They concluded, since it was so nearly

gone, they

would eat the rest of it and postpone making any maple sugar until the

next

day. So they spread what syrup remained on their slices of bread and

ate it.

Then they put away their saucers and spoons under the box and called

Carlo and

Tom. They were about to start for home when

Margaret

reminded Frank that they ought to go around to the trees and collect

the sap

again; for Beechnut had told them to collect it twice a day, or the

dishes

would get more than full. But Frank was tired, and he did not feel

inclined to

work any more with the sap that day. He did not believe, he said, that

the

dishes would get full; "and besides," he added, "perhaps we

shall come this afternoon and collect it." His reasoning satisfied Margaret, and they

went up

the path and across the bridge to the highway. Little streams of water

produced

by the melting of the snow were running along the road, and they were

obliged

to select their way very carefully. It was just dinner time when they

reached

home. Frank found that he had no inclination to

go in the

afternoon to collect the sap. He got engaged in other occupations, and

then,

too, after eating so large a quantity of maple syrup as he had that

morning his

interest in sugar making and in everything that pertained to it had

very much abated. About sunset, after supper that night, as

he was

sitting in the doorway of a small workshop near the barn, Beechnut came

along

and entered the shop. Frank was making a windmill. He had already given

Beechnut an account of how he and Margaret had spent the morning, and

now he

said, "Don't you think we managed pretty well in our sap boiling?" "Pretty

well," replied Beechnut. "I think we managed very well," said

Frank. "You managed very well in all respects but

one," Beechnut responded; "and in that you managed very badly." Frank supposed that Beechnut referred to

their having

eaten all their syrup without waiting for it to turn into sugar. He

paused a

moment and then said, "Yes, I told Margaret that we ought to have saved

some of it for mother." "Oh, I don't mean. that," said Beechnut.

"Then where was our bad management?" Frank inquired. "In not collecting the fresh sap before

you came

home," replied Beechnut. "But we were going down this afternoon,"

explained Frank. "And have you been down?" Beechnut asked. "Why — no — " Frank answered hesitatingly.

"I was too tired." "Then I suppose," said Beechnut, "that

some of the dishes are full and running over, and they will continue to

run

over all night. No matter if you were tired, you ought to have taken

the pail

and gone around to the trees and emptied all the dishes, and then have

carried

the pail and put it safely under the box. To-morrow morning you would

have had

a double supply, for the dishes would all be full again by that time. I

advise

you to go and empty them now." "It is too late," said Frank. "No," said Beechnut, "the sun is half

an hour high, and you could do the whole business in half an hour. It

will be

some trouble, and yet not nearly trouble enough." "What do you mean by that?" Frank asked. "It will not be trouble enough to punish

you

properly for having neglected to do it at the proper time," responded

Beechnut. "When you are a man, if you manage your business in such a

way

as that, you will get everything behindhand and in disorder. You had

better

learn to do things as they should be done while you are a boy." Frank knew this was very good advice. But,

because he

was so much interested in his windmill and because he was unwilling to

go to

the shore alone, he concluded to let the sap run. He did not think many

of the

dishes would get full, and he would go down and gather the sap early in

the

morning. Margaret would go with him then, he said. He did not, however, feel satisfied or

happy. In his

fancy he could see the dishes full to overflowing, with the sap running

down

the sides on the snow or among the leaves and moss which covered the

ground,

and this caused him a good deal of mental discomfort. It turned out as Beechnut had predicted,

for when Frank

and Margaret went to the riverside in the morning they saw plainly that

much of

the sap had gone to waste during the night. They were more careful

afterwards,

and when the weather favored a generous run of sap, they gathered it

twice a

day. On the whole they did very well, but at last their sugar-making operations were brought to a sudden termination. They had been boiling most of an afternoon, and when the supper bell called them home they got their things together and left them as usual on the beach. It had begun to rain a little after supper, and at bedtime they heard it raining very hard.  The first thing in the morning Frank went

to his

window, and, behold, there was a great freshet. The river had risen

rapidly,

the ice had broken up, and the big cakes were hurrying down the stream

grinding

and crushing one another as they went. A few days later, when the water had

subsided, Frank

visited the beach. Everything he had left there had been swept away. ble enough to punish you

properly for having neglected to do it at the proper time," responded

Beechnut. "When you are a man, if you manage your business in such a

way

as that, you will get everything behindhand and in disorder. You had

better

learn to do things as they should be done while you are a boy." Frank knew this was very good advice. But,

because he

was so much interested in his windmill and because he was unwilling to

go to

the shore alone, he concluded to let the sap run. He did not think many

of the

dishes would get full, and he would go down and gather the sap early in

the

morning. Margaret would go with him then, he said. He did not, however, feel satisfied or

happy. In his

fancy he could see the dishes full to overflowing, with the sap running

down

the sides on the snow or among the leaves and moss which covered the

ground,

and this caused him a good deal of mental discomfort. It turned out as Beechnut had predicted,

for when Frank

and Margaret went to the riverside in the morning they saw plainly that

much of

the sap had gone to waste during the night. They were more careful

afterwards,

and when the weather favored a generous run of sap, they gathered it

twice a

day. On the whole they did very well, but at

last their

sugar-making operations were brought to a sudden termination. They had

been

boiling most of an afternoon, and when the supper bell called them home

they

got their things together and left them as usual on the beach. It had

begun to

rain a little after supper, and at bedtime they heard it raining very

hard. The first thing in the morning Frank went

to his

window, and, behold, there was a great freshet. The river had risen

rapidly,

the ice had broken up, and the big cakes were hurrying down the stream

grinding

and crushing one another as they went. A few days later, when the water had

subsided, Frank

visited the beach. Everything he had left there had been swept away. |