| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XIV OLD POLYPOD Frank was impulsive and eager to lead.

Margaret was

quiet and submissive and generally very willing to follow. Thus they

agreed

very well together and seldom got involved in dispute; and yet Frank

was often

very capricious and went from one thing to another in his plays drawing

Margaret with him, each undertaking being soon abandoned in its turn. For instance, one summer morning after

breakfast,

when he and Margaret came out to play, he proposed that they should go

and work

in the garden. He had a corner there which Beechnut had assigned him,

and, in

this corner he had sown flower seeds about a month previous. The plot

was now

covered with a very luxuriant vegetation, weeds and flowers having come

up

together in great profusion. Frank had neglected his garden corner

entirely since

putting the seeds into the ground, but now the idea struck him that it

would be

good amusement to put it in order. Margaret assented to the proposal.

So he

went into the barn to get his little wheelbarrow and the tools. He loaded up his wheelbarrow with a great

variety of

implements that he might be sure to have all he should need, and

proceeded

toward the garden. Margaret followed, gathering up such tools as fell

off from

the wheelbarrow, and dragging them on as well as she could. Frank worked in the garden a short time —

long enough

to make considerable litter in the walk opposite his plot, with the

weeds he

pulled out from among the flowers and threw down there. Then he became

tired.

He told Margaret it was a fine day to go fishing, and that he thought

they had

better go down to the pier and see what they could catch. He would

leave the

tools and the wheelbarrow where they were, he said; for he was coming

back to

work in his garden after he had rested himself a while, fishing. To find his fishline caused him quite a

little

trouble. He looked in the proper place for it, but it was not there. He

was

sure he had put it there after he last used it. Somebody must have

taken it

away, he said, and he went to ask Beechnut if he had seen it anywhere. "Yes," replied Beechnut, "it is around

the corner of the house by the well. You left it there day before

yesterday

when you came home from fishing and went to the well to get a drink of

water." "Oh, so I did," said Frank. "Now I

remember." The hook was off from Frank's line. He had

more hooks

somewhere in a box, but he did not know exactly where. He looked in all

the

probable places that he could think of and inquired of every one he

met; but

the hooks could not be found. After fretting a little at this vexation,

and wishing

somewhat pettishly, "that people would not take his things," he

contrived to make a hook of a large pin which his mother gave him, and

went

down to the pier. He threw his line out into the water, sat down on a

log and

began watching the cork for indications of a bite. Margaret stood by

his side.

with her eyes fixed very intently on the cork. But the fish did not bite, and Frank soon

tired of

this sport. He drew in his line, saying it was of no use to fish that

morning.

He declared that he did not believe there was a fish in the river.

Besides, he

did not blame them for not biting at a pin. Frank was beginning to get

out of

humor. He wound up his line and went back to the house. There was a wagon standing in the yard.

"Ah,

Margaret!" he exclaimed, "this wagon is just the thing. Let us get in

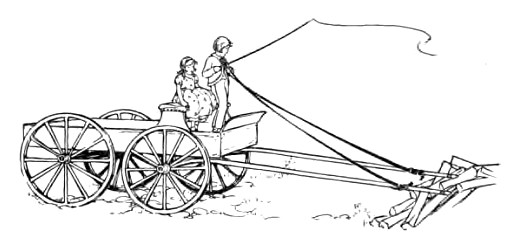

and have a ride." He leaned his fishpole against a tree that was near by and helped Margaret into the wagon. Then he took the reins and fastened one of the ends to each shaft. After that, with great labor he drew the wagon along to a woodpile and rested the shafts on the wood so as to keep them in a horizontal position. Margaret was in the wagon and she was much pleased to be drawn, and urged Frank to go on and give her a ride in the wagon all about the yard. But Frank said she was too heavy.  He now got into the wagon, took the reins

and whip,

and began to drive. However, he found that the rest of the harness

which was

lying on the floor of the wagon under his feet was somewhat in his way.

So he

threw it out on the grass. He pretended that the wagon was a ship at

sea in a

storm, and he was throwing the cargo overboard. This idea amused both

him and

Margaret very much. When the harness was all out Frank

gathered up the

reins again and drove on, talking all the time about the scenery

supposed to be

in view, and the various objects and incidents which he fancied as

occurring by

the way in their imaginary ride. Sometimes he would pretend that they

were

going through a gloomy wood and that he was afraid they would meet

robbers; and

he would whip his horses and urge them on with the utmost vigor to

escape from

the danger. Then he would come into an open country, very rich and

beautiful,

and would point out to Margaret the streams and lakes and waterfalls,

or the

lofty precipices and the dark mountains which came successively into

sight. At

length he would rein in at the door of a tavern, and hold long

conversations

with the landlord about the accommodations which he wanted and the

terms on

which the landlord would furnish them. Frank entertained himself and Margaret in

this way

for about a quarter of an hour, and then he became tired of riding. He

got down

from the wagon and helped Margaret down. For a moment he paused while

he looked

at the harness lying on the ground, with an indistinct idea in his mind

that it

was his duty to put it back in the wagon before he went away. But he

thought he

would come back pretty soon to take another ride, and meanwhile he

would go

into the workshop and see what Beechnut was doing. The workshop was a large room in one of

the sheds;

and Frank and Margaret had heard a hammering there and concluded

Beechnut was

busy inside. They found him mending some hay rakes. He was standing

before a

great bench on which were several of the rakes he had brought in to be

repaired. One needed a new tooth, another a new handle, while a third

needed a

wedge to tighten a loose joint. Frank climbed up and sat on the edge of

the bench

near where Beechnut was working; and he reached a hand to Margaret and

helped

her up so she could sit by his side. Beechnut was driving in a wooden

peg which

was to form a new tooth for the rake that he was mending. "O Beechnut!" said Frank, "that

reminds me — you promised a great while ago to make me a wooden horse,

and you

have not done it. I don't think you keep your promises well

at

all." "That is a heavy charge to bring against

me," said Beechnut. "When did I promise it should be made?" "I don't know," replied Frank. "You

didn't say any particular time. You were to make it for me sometime or

other,

and you have never made it at any time." "There is more time coming," said

Beechnut,

"plenty of it. Perhaps I shall make the wooden horse sometime or other

yet." "But you ought to have made it before

now,"

argued Frank. "To cause me to think you are going to make it when you

don't make it, is deceiving." "Hi-yo!" said Beechnut, "what a

character I am getting." "It is as wrong to deceive anybody as it

is to

tell a lie," declared Frank. "Always?" asked Beechnut. "Yes, always," answered Frank very

positively. "Once I knew a boy," said Beechnut

speaking

very gravely, "who had a hen; and as he thought that she would forsake

her

nest if he took the eggs all out and left it empty, he made a wooden

egg and

left it there for a nest egg. He wished to make the poor hen think it

was a

real egg, and so deceive her." "I know who you mean," said Frank.

"You mean me. But that is a different thing. She was only a hen. I

meant

one does wrong to deceive men." "Well, I once knew a man," continued

Beechnut, "who had only one arm. The other had been shot off in the

wars.

He found that it was rather disagreeable to other people to see a man

with one

of his arms off at the shoulder. So he had a cork arm made with a hand

to it,

and it was so exactly like a real arm that nobody observed any

difference. He

kept a glove on the cork hand, and every one was deceived and thought

it was a

real hand." "I could tell," affirmed Frank. "Do you think," asked Beechnut, "that

it would be wrong for a man to wear a cork arm or a cork leg so exactly

made

that people would think it was a real one?" "Yes," declared Frank desperately. He did

not know how else to get out of the corner into which Beechnut had

driven him. "Well," said Beechnut, " we won't talk

about that any longer, and as soon as I have finished this rake I will

go and

make a wooden horse." In a few minutes the rake was done, and

Beechnut

conducted Frank and Margaret to the woodshed to look at a great log

which he

had laid aside some time before for the body of the wooden horse. It

was a log

of a very irregular shape having some rude resemblance to a horse.

Beechnut had

observed this odd appearance of the log the winter before when it was

in the

woodpile in the yard, and had thrown it aside intending to put legs to

it some

day for the children; but the convenient time for doing this had not

arrived

until now. "There," said Beechnut as he pointed out

the log to Frank and Margaret, "what sort of a horse do you think that

will make for you?" "Excellent," replied Frank. "Let's

haul him to the shop and put his legs in immediately." So Beechnut and Frank, after rolling the

log over and

over several times to get it out where they could take hold of it,

lifted it up

and lugged it into the shop. Margaret tried to help by taking hold of a

branch

which represented the tail and lifting with the little strength which

she had

at her disposal. Thus the monster was finally got into the shop and

tumbled

down there on the floor. Beechnut then made legs for the horse and

bored holes

with a great augur in the log for their insertion. While he was doing

this,

Frank asked what name his horse should have when he was finished. "You must name him yourself," said

Beechnut. "I am going to make him a galloping horse. He will have three

pairs of legs, and they will be of different lengths, and when you rock

him

back and forth on them you can suppose that he is galloping. You had

better go

and ask Wallace what would be a good name for an animal with six legs."

"All right," said Frank, "I will; or

no," he added, after a moment's thought, "it will be better for you

to go, Margaret, because you see I want to stay and watch Beechnut

finish the

horse." "But I want to stay, too," said Margaret. "Why, that isn't of so much consequence,"

argued Frank. "You know it is necessary I should learn how horses are

made; for perhaps I shall have to make one myself some day. I may want

to make

a little one for you, if I can find the right kind of a log next

winter. So it

is better you should go and ask Wallace about the name." Margaret was easily persuaded in such

cases as these,

and though she had no great confidence that Frank's plans of making a

horse for

her would ever be accomplished, she consented to go on his errand. In

due time

Frank saw her returning, and he called out to know what Wallace had

said the

name was to be. "It is Polly something," replied Margaret.

"He has written it down on this paper." Frank took the paper, repeating at the

same time in a

tone of contempt the name which Margaret had suggested, "Polly!" said

he, "Polly is no name for such a horse as this." He opened the paper and read what was

written on it

to Beechnut and Margaret, thus: "I think you had better call him Polypod."

Frank threw back his head and laughed.

"Oh,

Polypod!" he exclaimed, "what a name!" The legs of the horse were soon finished.

They were

formed of short stakes sharpened a little at one end and driven firmly

into the

augur holes which had been bored to receive them. They were set in such

a

manner as to slant outward to prevent the horse from falling over on

his side.

The middle pair of legs was a little longer than those before and

behind, and a

rider seated on the horse and rocking it to and fro would produce a

sort of

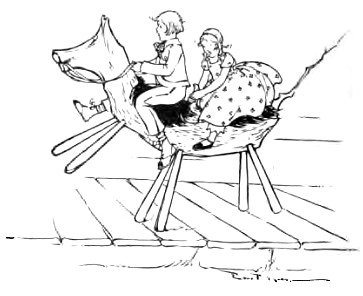

jolting motion. When the work was done they carried the horse out to a plank platform at the end of the house, and established him there. Beechnut brought two buffalo robes from the barn, and folding them twice, he placed them on the horse, one behind the other. The foremost formed a saddle for Frank, and the other a pillion for Margaret. It happened there was a stub of a branch growing out of the log between Margaret's seat and Frank's, and this was very convenient for Margaret to enable her to hold on.  To add interest to the sport Beechnut

taught the

children a song to sing which he made up for the occasion, and then he

went

away leaving them singing and riding old Polypod, keeping time with

their music

to the jolting of the horse. The song was this: High

and low

Fast and slow, Over the hills, away we go. Hi, old Polypod! Ho, old Polypod! Tumbling, rumbling, stumbling Polypod. The children sang this stanza with great

glee at the

top of their voices. An hour or two later, Beechnut, in looking

about the

premises, found. the traces of disorder which Frank and Margaret had

left in

the garden and around the wagon in the yard. He put away the things

Frank had

left out of place and noted the time it required to do so. It took him

ten

minutes. He then went in search of Frank. "Well, Frank," said he, "how do you

like old Polypod?" "Very much, indeed," answered Frank.

"Have I fulfilled my promise to your satisfaction?" continued

Beechnut. "Yes," said Frank, "entirely." "Now I have a charge against you," said

Beechnut. "You have been at work in the garden, and you have left the

wheelbarrow and the tools and ever so many weeds in the walks. Then you

went to

play in the wagon, and finally left it out of its place, and with the

reins

tied to the shafts, the harness on the ground, and everything in

confusion." Frank appeared quite astounded at these

accusations.

He did not know what to say. "Are you guilty or not guilty?" Beechnut

asked. "Why, guilty, I suppose," replied Frank;

"but I will go and put the things right away." "No," said Beechnut, "that is done

already. Everything is put away except your fishpole. That is your

property and

I have nothing to do with it. But it is my business to take care of the

garden

and the wagon. So I have put them in order, and all you have to do is

to submit

to a proper punishment for putting them out of order." "Well," responded Frank, "I will. What

is the punishment?" "You must pay double damages," said

Beechnut. "It took me ten minutes to clear up after you, and you must

do

work for me equal to twenty minutes; but as your time is not worth more

than

half as much as mine it will take you forty minutes to do the work." "What is the work to be?" Frank inquired. "Turning the grindstone after supper for

me to

grind the scythes," replied Beechnut. Frank made no objection. In fact he went

at this task

so industriously and was so pleasant about it that Beechnut released

him at the

end of half an hour. Beechnut never scolded; yet he always

punished the

boys he had dealings with for their faults and delinquencies. Sometimes

his

punishments were of a very odd and whimsical character and afforded

great

amusement — while they answered the

purpose of punishments perfectly well: It is true that the boys were

not obliged

to submit to them, but they generally did so of their own accord, for

the

punishments were sure to be reasonable, and Beechnut was very

good-natured in

inflicting them. |