| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

XV THE BEAR HUNT Late in the summer, a large black bear

that had been

living remote among the mountains became tired of the dismal solitude

of its

abode, or else perhaps found difficulty in obtaining food enough far

off in the

forest, and came toward the settlements of men to see what it could

find. It

was very successful in this expedition. In a lonely field near a

farmhouse it

discovered a flock of sheep sleeping quietly one midnight. The bear

crept up to

them and seized a lamb in its powerful jaws and then ran off into the

woods.

The lamb set up a loud and incessant bleating, though the sound grew

fainter

and fainter as it was borne off through the thickets. The whole flock of sheep was aroused by

these sudden

cries, and all began to bleat and to run in a panic toward the house.

They all

ran thus except one, the mother of the lamb that was carried away. She,

instead

of going with the others, ran into the gloomy thickets where her lamb

had

disappeared, and resolved to attack the enemy if she could overtake it,

whatever it might be. She, however, did not succeed in overtaking the

bear, and

ran to and fro completely bewildered. The bear knew perfectly the way

it was to

go. It had eyes that could see even in the densest recesses of the

forest, and

in the darkness of midnight. The farmer came out with a lantern to

learn the cause

of the commotion, but he could not determine whether any of the sheep

or lambs

had been carried away. The darkness and the confusion prevented him

from

counting those that remained to see if they were all there. He presumed

from

the bleating of the mother sheep that one of the lambs was gone. In the morning all doubt was at once

removed; for the

spot where the bear had struggled with its prey was plainly to be seen,

and its

track could easily be traced into the woodland, marked, where the

ground was

soft by the impression of its footsteps, and at other places by blood. On making these discoveries the farmer's

indignation

was roused to the highest pitch. He called his neighbors to see the

tracks made

by the bear. They had flocks and herds exposed to the same danger and

soon

formed a plan for arming themselves and setting off into the woods in a

company

to endeavor to find the bear in its retreat and kill it. For arms the farmers got out all the

muskets, fowling

pieces, and pistols they could find in their houses; and those who had

nothing

that would shoot supplied themselves with pitchforks, hatchets, and

stout

clubs. One man made a sort of spear of the point of a scythe which he

contrived

to fasten into the end of a handle that had once belonged to a

pitchfork. It

made a very formidable-looking weapon, and the man brandished it in the

air

before him, and said that all he wanted now was to see the bear coming

at him

with its mouth open. He would give it something to swallow not quite as

tender

as the flesh of that lamb. In the meantime, the messengers galloped

from

farmhouse to farmhouse spreading the tidings. One of them came to Mr.

Henley's

and told Beechnut the news, in hope that some of Mr. Henley's workmen

might go

with them. It happened that the workmen were all away. Margaret was

just going

down to the river to join Frank, who was on the little pier, fishing;

but her

attention was arrested by seeing the horseman ride rapidly into the

yard. When

he stopped before Beechnut, who was saddling a horse that was hitched

to a post

near the- barn, she went to hear what was the matter. After the

messenger had

finished what he had to say he rode away as fast as he came. Beechnut left the saddle loose on the back

of his

horse, and hurried into the house, while Margaret walked slowly and

thoughtfully down toward the pier. She was thinking of the bear and

intending

to tell the story to Frank. Frank had heard the footsteps of the horse

as it came

galloping along the road, and had looked around to see what was the

matter. He observed that the messenger, after a

moment's

conversation with Beechnut, went galloping away. This excited his

curiosity. He

stood, accordingly, on the pier holding his fish-pole in his hands with

the

line in the water, but with • his face turned toward Margaret. As soon

as she

came near enough to hear him he called out, "What was it that man

galloped

into the yard about? " "About a bear," replied Margaret. "What about a bear?" asked Frank very

eagerly. "It is about a bear that came out of the

woods

and carried off a little lamb," said Margaret, who had now reached the

pier. "The men are all going off into the woods to shoot the bear and

bring the lamb home." In a very hurried and excited manner,

Frank

immediately laid his fishpole down on the pier, placed a flat stone

across it

to keep it steady, and set off for home. Margaret ran after him, urging

him to

wait for her. Frank, however, was too much stirred by the intelligence

he had

received to pay any heed to Margaret's calls. He made his way as fast

as he

could into the yard to find Beechnut. He caught a glimpse of him going

into the

shop. Frank followed and found him examining an old gun he had taken

down from

a high shelf. "Are you going into the woods to shoot the

bear?" asked Frank. "I am going into the woods," replied

Beechnut; "but I do not expect to shoot the bear." "Has my mother given you leave to go?"

Frank inquired. "Yes," was Beechnut's answer. He had been to the house and asked

permission to

accompany the expedition. Mrs. Henley had been unwilling at first to

give her

consent. But Beechnut said that they had flocks of sheep to be defended

as well

as the neighbors, and that it was incumbent on him, since all the men

of the

farm were away, to go with the other farmers. Whatever might be the

difficulty

or the danger, he ought to take his share with the rest. So finally

Mrs. Henley

consented. Beechnut explained all this to Frank who

said,

"I mean to go too. I will ask my mother." He ran off to the house, but in a few

minutes

returned looking very downcast and disconsolate. Beechnut was still at

work on

the gun, and his attention was so absorbed by it that he paid no heed

to Frank.

Margaret was standing by looking at the gun with an expression of

mingled

curiosity and awe. She glanced up when Frank came into the shop, and

said, "Will

she let you go?" "No," replied Frank peevishly; ." and

I don't see why. I might go as well as Beechnut." "She will not let you go then?" said

Beechnut, snapping the hammer of the gun back and forth in his attempt

to put

it in order. "How provoking!" "Yes," Frank responded, "it is very

provoking indeed." "If I were you," said Beechnut, "I

would do something or other very desperate. I would fret about it all

day." Frank was silent. "You will not find another thing so good to fret about in a twelvemonth," continued Beechnut. "Here now is a boy that his mother will not allow to set off in a company of fifty men with dogs and guns to make a tramp of six miles through the woods among the mountains hunting a wild beast; and see how patient the little fellow is!"  So saying, Beechnut began to pat Frank

gently on the

back. Frank seized a leather strap which chanced to be lying on the

bench, and

gave Beechnut a great whack across the shoulders with it. Then he ran

out of

the shop. He tried very hard to look cross until he was out of sight,

but he

did not quite succeed. Just as he was passing out of the door he

burst into

an involuntary laugh. He recovered himself almost immediately, and

Beechnut

having followed him to the door saw him standing there, pretty near,

looking as

sullen as ever. "Poor little lamb!" said Beechnut in a

tone

of great condolence. On hearing these words, Frank made a dash

at Beechnut

intending to pound him with his fists; but Beechnut evaded him by

running

around the horse. As he ran he said, "I meant the lamb that the bear

carried away — not you." "No," asserted Frank, "you meant me. I

know you did." Beechnut now stopped to put the saddle

properly on

the horse and to fasten the girths. He then went into the shop, and

came out a

moment afterwards carrying a small light ax. With that in his hand he

mounted

the horse and started to ride away. "Are you not going to take the gun?" asked

Frank. "No," replied Beechnut. "Why not?" Frank inquired. "Oh, there are various reasons," Beechnut

responded. He was advancing across the yard toward

the gate, and

Frank was trotting along by his side holding on to the stirrup. "The gun is out of order," Beechnut

continued, "and I am afraid it would not go off. If it should go off, I

am

afraid it would kick me over. If it did not kick me over, I am afraid

it would

shoot one of the men; and if it did not shoot any of the men, I am

afraid it

would not hit the bear. So good-by. Poor little lamb!" Frank stooped and seized a handful of

grass which he

threw at Beechnut as he cantered away. Then he walked back to meet

Margaret. He

told her Beechnut was the greatest tease that ever he knew, and he

hoped the

bear would catch him in the woods and eat him up. Frank now went and got a wooden gun

Beechnut had made

for him some time before, and amused himself and Margaret for more than

two

hours in rambling about the yard and garden, and shooting at various

objects

which he made believe were bears. The men that were to go on the hunt met at

the house

of the farmer whose flock had been attacked. Here they agreed on the

rules of

the expedition. They were all to proceed together, following the track

of the

bear as long as the track could be seen. Then they .were to separate

into a

number of parties, each under its own leader, and proceed by different

paths,

though in the same general direction. They were to be very careful not

to fire

a gun unless they should actually see the bear, so that the report of a

gun in

the forest would be a signal to all who heard it to go immediately to

the spot

whence the sound came. In case the several parties should become so

widely

separated that some failed to hear the guns, or in case the bear should

not be

seen and no guns fired, they were each to keep on as far as they

thought they

could safely go and get back that night. These arrangements being

agreed on,

the expedition began its march. The men walked in single file following

the track of

the bear, with the more experienced and sagacious hunters in front to

keep a

sharp watch. Some of the young men in the company laughed at Beechnut

for

bringing an ax. They asked him whether he thought that an old bear was

going to

stand still like a maple tree while he came up with his ax to cut the

bear

down. Beechnut took all this raillery in good part and trudged

patiently on in

his place in the line with the ax on his shoulder. After getting about a mile and a half into

the woods,

the leaders of the expedition lost sight of the track and could not

recover it.

The company then divided into several distinct parties and went on at a

little

distance from each other so as to explore a considerable breadth of

forest as

they advanced. Beechnut was attached to a party of six

led by an old

hunter whom the men called Uncle Harry. He had joined this division

because he

had more confidence in Uncle Harry than in any of the other commanders.

The

rest were noisy and talkative and were continually calling out to the

company

to go this way or that, and directing attention to discoveries which

always

turned out to amount to nothing. Uncle Harry said little and made no

pretensions and yet was very observant and watchful. Beechnut therefore

concluded he would have the best chance of seeing the bear by following

Uncle

Harry. The old hunter knew the country perfectly

well, and

he formed a correct judgment of the route which the bear, would be

likely to

take. He pushed on, however, without seeing any signs of the bear for

more than

three miles. At length, just as they were entering a wild and dismal

glen

almost surrounded by rocky precipices, Uncle Harry suddenly stopped and

said,

"Hush!" He pointed up the glen. The men all

looked, and there

on the ground under an oak tree they saw a monstrous black bear sitting

with

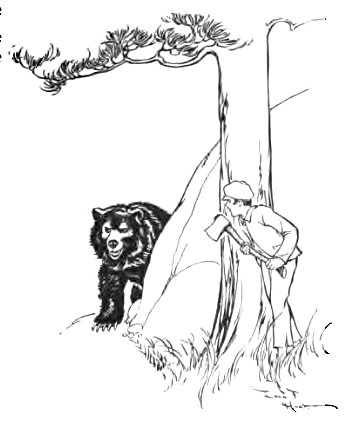

its fierce glaring eyes turned full on them. Beechnut glanced around the glen to see if

there were

any way by which the bear could escape in case it was attacked by the

men and

wounded. He noticed a path leading up the rocks at one side of the

glen, and

this seemed to be the only egress except that blocked by the men.

Immediately

he left the party and running into a thicket stole round by a circuit

until he

came to the path about halfway up the ascent. Just as he reached this point he heard a volley discharged from the guns. He sheltered himself behind a great tree, and then peeping around from one side looked down into the glen. The bear had disappeared. It had been slightly wounded by one of the guns and had scrambled up into the oak tree. The men were loading their guns anew. Presently they fired a second time.  The bear was again slightly wounded, and

it hastily

came down the tree and rushed toward the path Beechnut was guarding. He

stood

all ready with his ax while the bear scrambled up the hill. The instant

the

creature came within his reach he dealt its head a tremendous blow that

felled

the bear dead to the ground. The report of the guns and the shouts of

the men

brought one of the other parties to the spot. The rest had wandered too

far

away to hear them. By using the stems of young and slender trees, the

men who

were assembled made a sort of handbarrow to put the carcass of the bear

on and

carry it home. They found a road in returning which took them back by a

nearer

way than that by which they came. When they approached the settlements of

the farmers,

Uncle Harry and the other men told Beechnut to get on the barrow with

the bear

that they might carry him home in triumph. Beechnut wished to decline

this

honor, but the men insisted, and so he mounted the barrow and took his

seat on

the bear. The procession went on very well thus for

a short

distance, but presently came to a little bridge, which, though strong

enough

when first built, was getting old and decayed. Just as the men carrying

Beechnut and the bear were midway on the bridge it broke down, and half

the

party fell into the brook. Beechnut being the highest, fell the

farthest, and

the sharp end of one of the poles of the barrow entered his leg and

made a

shocking wound. For the rest of the way he had to be carried in

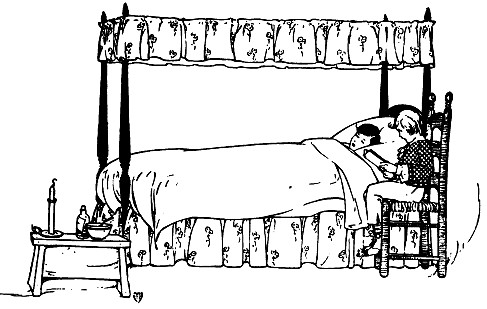

earnest. During the next two or three days Beechnut

suffered a

great deal of pain from his wound. He was feverish and restless

besides, and

thirsty all the time. Frank and Margaret went in occasionally to see

him, but

he could not talk much with them, and they soon went out. Once when

Frank

visited the bedside he asked Beechnut whether there was anything that

he could

do for him. "Yes," replied Beechnut, "if you will

go up into the mountains and bring me down a little brook so that I can

have it

running here by my bedside, and drink as much as I want, I will be

everlastingly thankful to you." Frank laughed and said he could not do

that; but he

would go to the well and get a pitcher full of cool water. Two days later, Frank and Margaret came to

Beechnut's

door one morning after breakfast and peeped into the room. Beechnut saw

them

and told them to come in. As they entered they perceived that he was

much

better. "How do you do this morning?" asked Frank. "Well!" replied Beechnut emphatically,

swinging his arms at the same time over his head. "Perfectly well. I

never

felt better in my life. I could mow an acre of grass this morning, if

they

would only bring it to me here on the bed. I have got to be still on

this bed a

week longer till the wound gets healed; but I am going to have

beefsteak for

breakfast. Think of that!" Frank said he did not think much of that.

He had been

having beefsteak for breakfast himself nearly every morning right

along. "But I am a convalescent," explained

Beechnut. He then attempted to sit up in his bed a

little by

way of showing how strong he was; but he found that he was not so

strong as he

had supposed, and on attempting to raise his head he was faint and

dizzy. He

was, therefore, very glad to lie down again. However, he gained a great deal of strength in the course of the day. Frank and Margaret came in several times to see him, and in the afternoon he was well enough to hear Frank read a story from a book, only Beechnut went to sleep during the reading. Frank looked a little disappointed when he turned around at the most interesting part of the story and saw that Beechnut was asleep. But the nurse seemed pleased and said the very best thing that could be done with a book where any one was sick was to read the sick person to sleep with it.  Beechnut was such a good patient and

obeyed the

directions of the physician and nurse so implicitly that he recovered

very

rapidly. At last he could sit up in an easy chair with his foot on a

cushioned

stool before him. Here he amused himself in making a pair of crutches,

and by

the time they were done he was vigorous enough to walk all about the

room on

them. Frank was so much pleased with this

operation that he

said he wished Beechnut would make him a pair of crutches. He tried

Beechnut's,

but they were too long. "Well," said Beechnut, "the first time

you get hurt so you cannot walk on your legs I will make you some

crutches." "No," replied Frank, "I want them at

once. But stop, I'll hurt myself now, and then I must have them." Then he tumbled down on the floor and

pretended to

have sprained his ankle. After that he went limping about the room

moaning and

making the most ludicrous contortions both of face and figure, greatly

to

Margaret's amusement. Beechnut finally agreed to make Frank a

pair of

stilts which he thought Frank would enjoy more than the crutches. Thus

the

matter was settled, and when the stilts were ready Beechnut was able to

go out

and show Frank how to use them. He now began to resume his usual work

and soon

was as hearty and well as ever. |