| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| II DESCRIPTION OF THE BOARD AND STONES THE board, or

"Go Ban" as it is called in Japanese, is a solid block of wood, about

seventeen and a half inches long, sixteen inches broad, and generally

about

four or five inches thick. It has four detachable feet or legs so that

as it

stands on the floor it is about eight inches high. The board and feet

are

always stained yellow. The best boards in Japan are made of a

wood called "Kaya" (Torreya

Nucifera) a species of

yew. They are also made of a wood called

"Icho" or Gingko (Salisburia

adiantifolia) and of

"Hinoki" (Thuya Obtusa) a kind of cedar. At all events they must

be of hard wood, and yet not so

hard as to be unpleasant to the touch when the stone is placed on the

board,

and the wood must further have the quality of resonance, because the

Japanese

enjoy hearing the sound made by the stone as it is played, and they

always

place it on the board with considerable force when space will permit.

The

Japanese expression for playing Go, to wit, "Go wo utsu," literally

means to "strike" Go, referring to the impact of

the stone. In Korea this feature is carried to such an extreme that

wires are

stretched beneath the board, so that as a stone is played a distinct

musical

sound is produced. The best boards should, of course, be free from

knots, and

the grain should run diagonally across them. In the back of the board there is cut a

square depression. The purpose

of this is probably to make the block more resonant, although the old

Japanese

stories say that this depression was put there originally to receive

the blood

of the vanquished in case the excitement of the game led to a

sanguinary conflict. The legs of the board are said to be

shaped to resemble the fruit of the

plant called "Kuchinashi" or Cape Jessamine (Gardenia floribunda), the

name of which plant by

accident also

means "without a mouth," and this is supposed to suggest to onlookers

that they refrain from making comments on the game (a suggestion which

all

Chess players will appreciate). On the board, parallel with each edge, are

nineteen thin, lacquered

black lines. These lines are about four one-hundredths of an inch wide.

It has

been seen from the dimensions given that the board is not exactly

square, and

the field therefore is a parallelogram, the sides of which are sixteen

and a

half and fifteen inches long respectively, and the lines in one

direction are a

little bit farther apart than in the other. These lines, by their

crossing,

produce three hundred and sixty-one points of intersection, including

the

corners and the points along the edge of the field. The stones are placed on these points of

intersection, and not in the spaces

as the pieces are in Chess or Checkers. These intersections are called

"Me" or "Moku" in Japanese, which really means "an

eye." Inasmuch as the word as used in this connection is

untranslatable, I

shall hereafter refer to these points of intersection by their

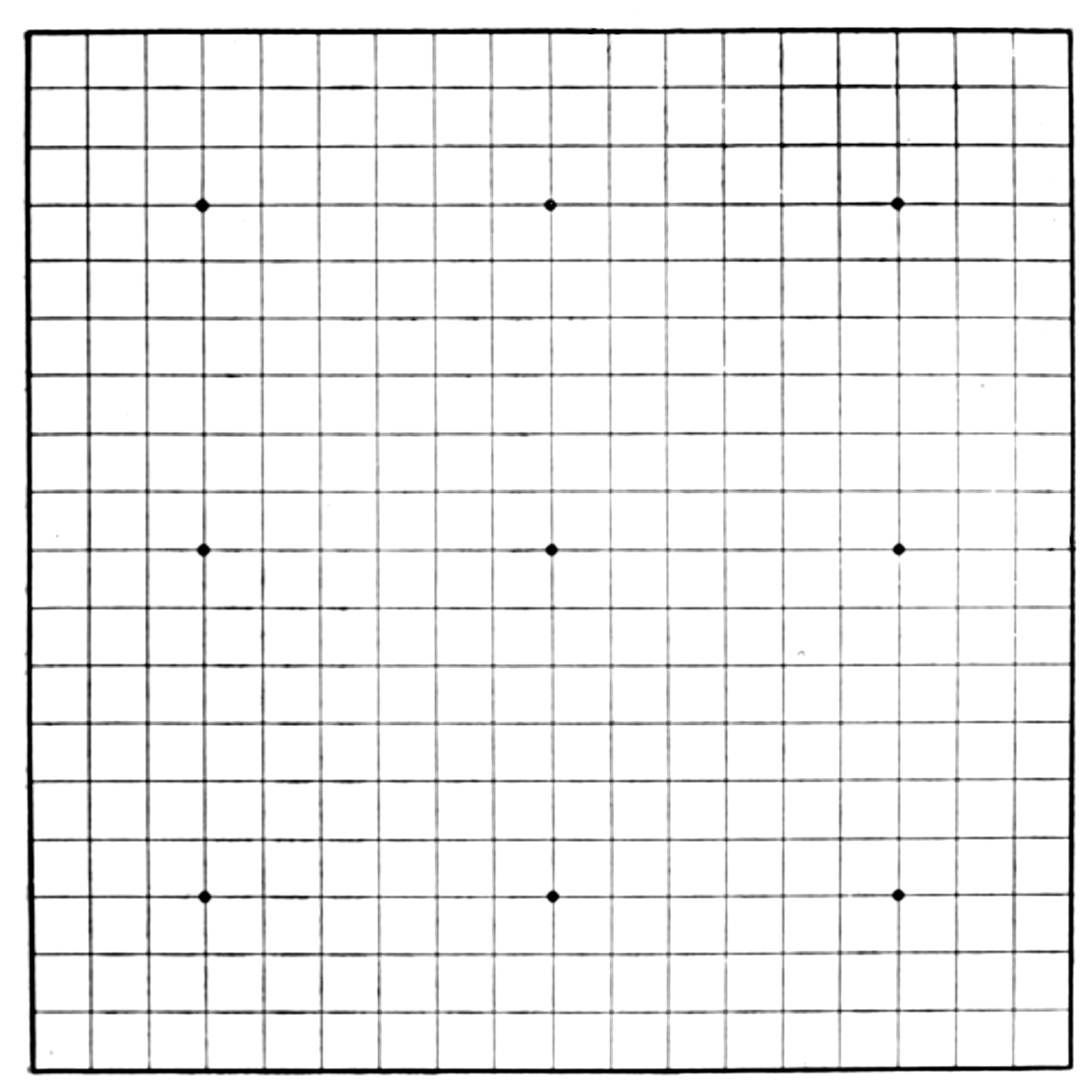

Japanese name. On the board, as shown in the diagram

(Plate 1), are nine little

circles. It is on these circles that the handicap stones when given are

placed.

They have no other function in the game, but they are supposed also to

have some sort of symbolical meaning. Chamberlain states

that these

spots or "Seimoku" are supposed to represent the chief celestial

bodies, and that the central one is called "Taikyoku"; that is, the

primordial principle of the universe. In the work of Stewart Culin

referred to

in the preface it is stated that they correspond to the nine lights of

heaven —

the sun, moon and the seven stars of the constellation "Tau" (Ursa

Major). Indeed the whole arrangement of the board is said to have some

symbolical significance, the number of crosses (exclusive of the

central one)

representing the three hundred and sixty degrees of latitude, and the

number of

white and black stones corresponding to the number of days of the

year; but

nowadays the Japanese do not make much of a point of the astronomical

significance of the board or of the "Seimoku." The stones or "Ishi" with which the game

is played are three

hundred and sixty-one in number, corresponding to the number of "Me"

or points of intersection on the board. One hundred and eighty of these

stones

are white and the remaining one hundred and eighty-one are black. As

the weaker

player has the black stones and the first move, obviously the extra

stone must

be black. In practice the entire number of stones is never used, as at

the end

of the game there are always vacant spaces on the board. The Japanese

generally

keep these stones in gracefully shaped, lacquered boxes or "Go

tsubo." The white stones are made of a kind of

white shell; they are highly

polished, and are exceedingly pleasant to the touch. The best come from

the

provinces of Hitachi and Mikawa. The black are made of stone, generally

a kind

of slate that comes from the Nachi cataract in Kishiu. As they are used

they

become almost jet-black, and they are also pleasant to the touch, but

not so

much so as the white. A good set is quite dear, and cannot be purchased

under

several yen. The ideograph formerly used for "Go ishi" indicates that

originally they were made of wood, and not of stone, and the old

Chinese

ideograph shows that in that country they were wooden pieces painted

black and

white. The use of polished shell for the white stones was first

introduced in

the Ashikaga period. In form the stones are disk-shaped, but

not always exactly round, and

are convex on both surfaces, so that they tremble slightly when placed

on the

board. They are about three-quarters of an inch in diameter, and about

one-eighth of an inch in thickness. The white stones are generally a

trifle

larger than the black ones; for some strange reason those of both

colors are a

little bit wider than they should be in order to fit the board.

Korschelt

carefully measured the stones which he used, and found that the black

were

seventeen-sixteenths of the distance between the vertical lines on his

board,

and about eighteen-nineteenths of the distance between the horizontal

lines,

while the white stones were thirteen-twelfths of the distance between

the

vertical lines and thirty-six thirty-sevenths of the distance between

the

horizontal lines. I found about the same relation of size in the board

and

stones which I use. The result of this is that the stones do

not have quite room enough and

lap over each other, and when the board is very full, they push each

other out

of place. To make matters still worse the Japanese are not very careful

to put

the stones exactly on the points of intersection, but place them

carelessly, so

that the board has an irregular appearance. It is probable that the

unsymmetrical shape of the board and the irregularity of the size of

the stones

arise from the antipathy that the Japanese have to exact symmetry. At

any rate,

it is all calculated to break up the monotonous appearance which the

board

would have if the spaces were exactly square, and the stones were

exactly round

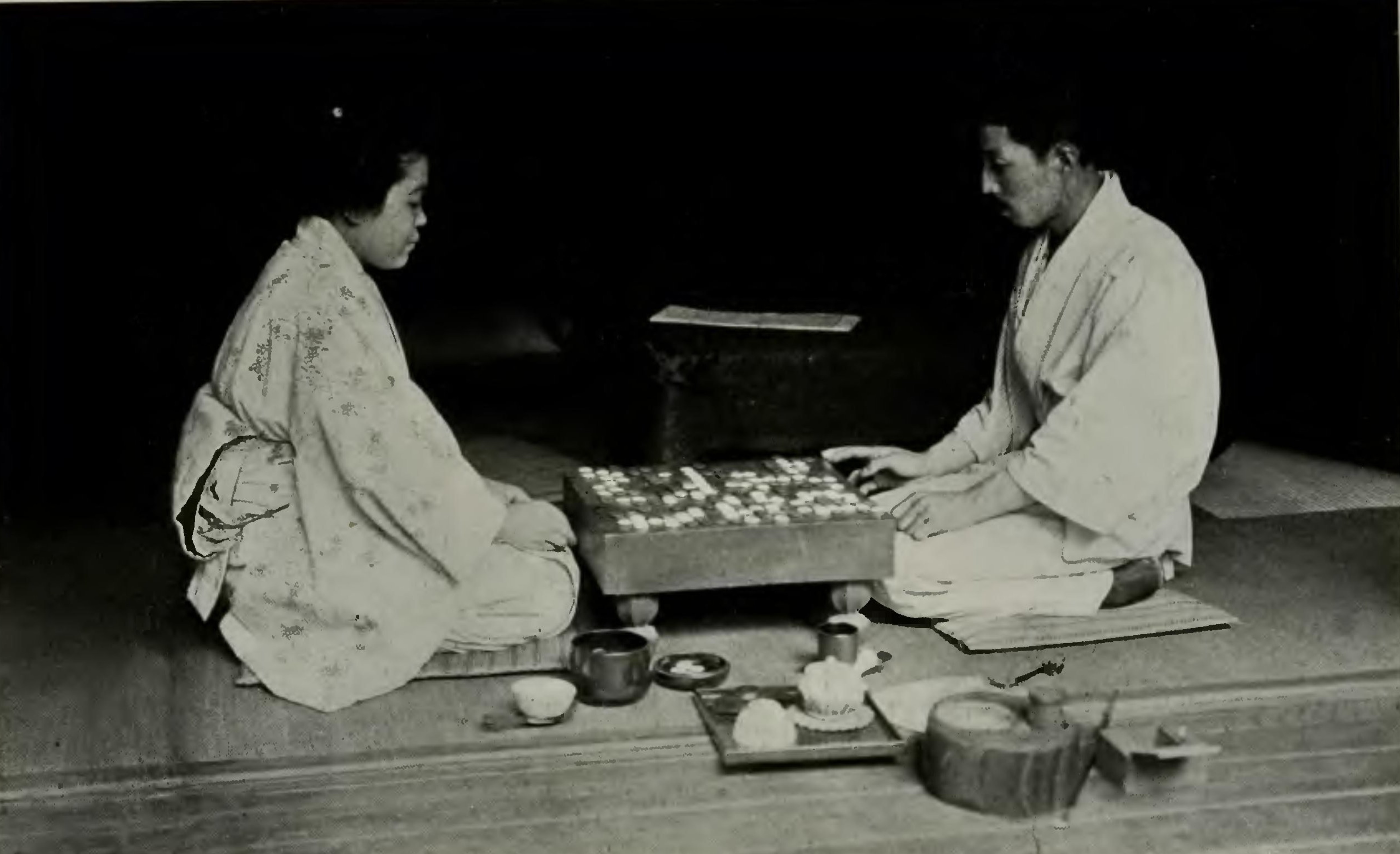

and fitted properly in their places. In Japan the board is placed on the floor,

and the players sit on the

floor also, facing each other, as shown in the illustration, and

generally the

narrower side of the board is placed so as to face the players. Since

the introduction

of tables in Japan Go boards are also made thinner and without feet,

but the

game seems to lose some of its charm when the customs of the old Japan

are

departed from. The Japanese always take the stone between

the middle and index fingers,

and not between the thumb and index finger as we are likely to do, and

they

place it on the board smartly and with great skill, so that it gives a

cheerful

sound, as before stated. For use in this country the board need not

be so thick, and need not, of

course, have feet, but if it is attempted to play the game on

cardboard, which

has a dead sound as the stones are played, it is surprising how much

the pleasure

of the game is diminished. The author has found that Casino chips are

the best

substitute for the Japanese stones.  PLATE 1. The Board Showing the "Seimoku."  Playing Go Originally the board used for the game of

Go was not so large, and the

intersecting lines in each direction were only seventeen in number. At

the time

of the foundation of the Go Academy this

was the size of board in use. As the game developed the present number

of lines

became fixed after trial and comparison with other possible sizes.

Korschelt

made certain experiments with the next possible larger size in which

the number

of lines in each direction was twenty-one, and it seemed that the game

could

still be played, although it made necessary the intellect of a past

master to

grasp the resulting combinations. If more than twenty-one lines are

used

Korschelt states that the -combinations are beyond the reach of the

human mind. In closing the description of the board it

may be interesting to point

out that the game which we call "Go Bang" or "Five in a

Row," is played on what is really a Japanese Go board, and the word

"Go Bang" is merely another phonetic imitation of the words by which

the Japanese designate their board. I have found, however, that the "Go

Bang" boards sold in the stores in this country are an imitation of the

original Japanese "Go ban," and have only seventeen lines, and are

therefore a little too small for the game as now played. The game which

we call

"Go Bang" also originated in Japan, and is well known and still

played there. They call it "Go Moku Narabe," which means to arrange

five "Me," the word "Go" in this case meaning

"five," and "Moku" being the alternative way of pronouncing

the ideograph for eye. "Go Moku Narabe" is often played by good Go

players, generally for relaxation, as it is a vastly simpler game than

Go, and

can be finished much more rapidly. It is not, however, to be despised,

as when

played by good players there is considerable chance for analysis, and

the play

often covers the entire board. |