|

|

||

| Kellscraft

Studio Home Page |

Wallpaper

Images for your Computer |

Nekrassoff Informational Pages |

Web

Text-ures© Free Books on-line |

|

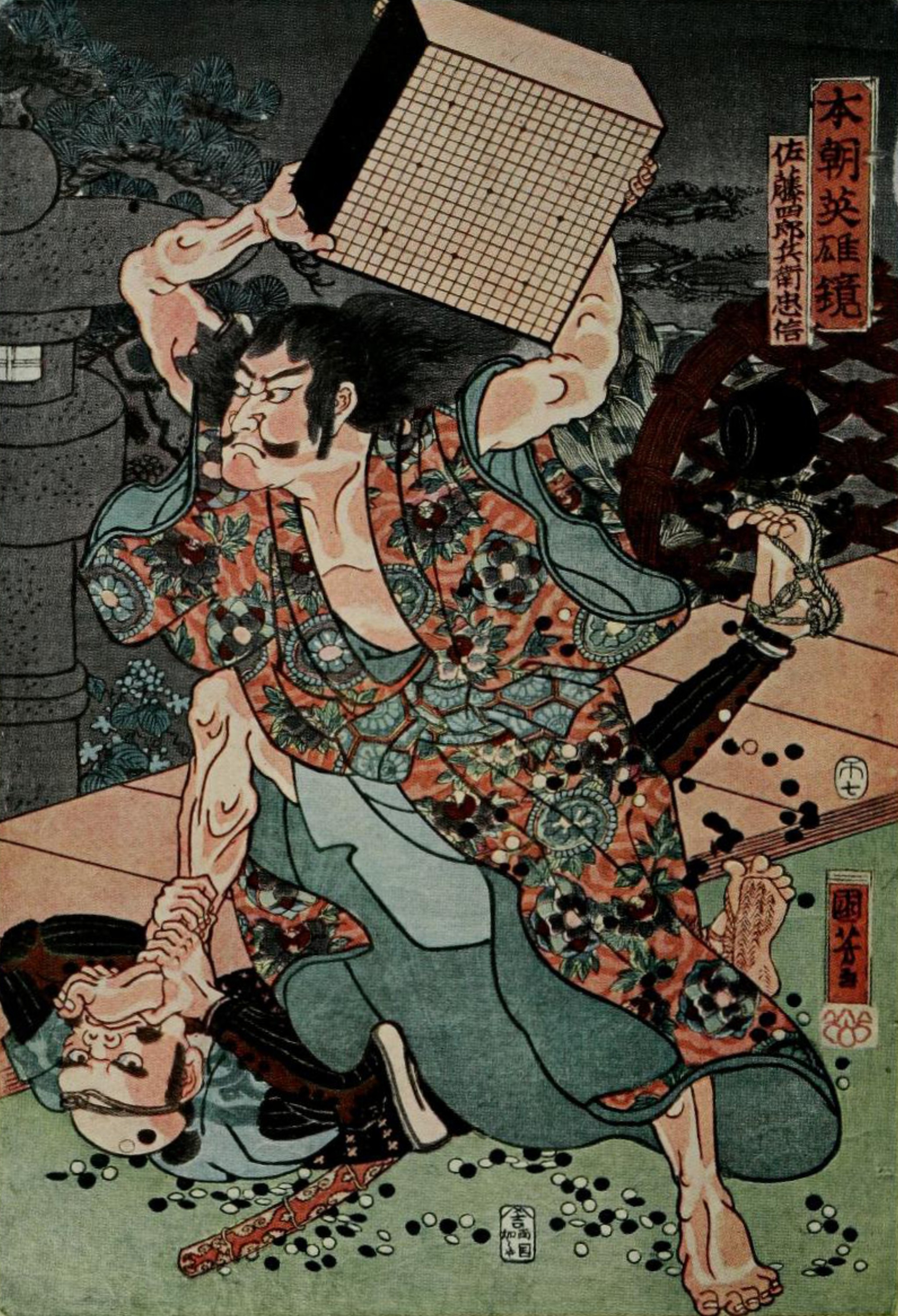

NATIONAL GAME OF JAPAN BY ARTHUR SMITH  MOFFAT, YARD & COMPANY 1908  SATO TADANOBU, A SAMURAI OF THE TWELFTH CENTURY, DEFENDING HIMSELF WITH A "GOBAN" WHEN ATTACKED BY HIS ENEMIES. From a print by Kuniyoshi THIS book is intended as a practical guide

to the game of Go. It is

especially designed to assist students of the game who have acquired a

smattering of it in some way and who wish to investigate it further at

their leisure. As far as I know there is no work . in the

English language on the game

of Go as played in Japan. There is an article on the Chinese game by Z.

Volpicelli, in Vol. XXVI of the "Journal of the China Branch of the

Royal

Asiatic Society." This article I have not consulted. There is also a

short

description of the Japanese game in a work on "Korean Games with Notes

on

the Corresponding Games of China and Japan," by Stewart Culin, but this

description would be of little practical use in learning to play the

game. There is, however, an exhaustive treatise

on the game in German by O.

Korschelt. This can be found in Parts 21-24 of the

"Mittheilungen der deutschen Gesellschaft für Natur and Völkerkunde

Ostasiens." The student could readily learn the game from Herr

Korschelt's

article if it were available, but his work has not been translated, and

it is

obtainable only in a few libraries in this country. In the preparation

of this

book I have borrowed freely from Herr Korschelt's work, especially in

the

chapter devoted to the history of the game, and I have also adopted

many of his

illustrative games and problems. Herr Korschelt was an excellent player,

and acquired his knowledge of

the game from Murase Shuho, who was the best player in Japan at the

time his

article was written (about 1880). My acquaintance with the game has been

acquired from Mr. Mokichi

Nakamura, a Japanese resident of this country, who is an excellent

player, and

whose enthusiasm for the game led me to attempt this book. Mr. Nakamura

has

also supplied much of the material which I have used in it. Toward the

end I

have had the expert assistance of Mr. Jihei Hashiguchi, with whom

readers of

the New

York Sun are already

acquainted. Wherever possible I have given the

Japanese words and phrases which are

used in playing the game, and for those who are not familiar with the

system of

writing Japanese with Roman characters, I may say that the consonants

have the

sounds used in English, and the vowels the sounds that are used in

Italian, all

the final vowels being sounded. Thus, "dame" is pronounced as though

spelled "dahmay." NEW YORK, April, 1908. THE game of Go

belongs to the class of games of which our Chess, though very

dissimilar, is an

example. It is played on a board, and is a game of pure skill, into

which the

element of chance does not enter; moreover, it is an exceedingly

difficult game

to learn, and no one can expect to acquire the most superficial

knowledge of it

without many hours of hard work. It is said in Japan that a player with

ordinary aptitude for the game would have to play ten thousand games in

order

to attain professional rank of the lowest degree. When we think that it

would

take twenty-seven years to play ten thousand games at the rate of one

game per

day, we can get some idea of the Japanese estimate of its difficulty.

The

difficulty of the game and the remarkable amount of time and labor

which it is

necessary to expend in order to become even a moderately good player,

are the

reasons why Go has not spread to other countries since Japan has been

opened to

foreign intercourse. For the same reasons few foreigners who live there

have

become familiar with it.

On the other hand, its intense interest is

attested by the following

saying of the Japanese: "Go uchi wa oya no shini me ni mo awanu,"

which means that a man playing the game would not leave off even to be

present

at the deathbed of a parent. I have found that beginners in this

country to

whom I have shown the game always seem to find it interesting, although

so far

I have known no one who has progressed beyond the novice stage. The

more it is

played the more its beauties and opportunities for skill become

apparent, and

it may be unhesitatingly recommended to that part of the community,

however

small it may be, for whom games requiring skill and patience have an

attraction. It is natural to compare it with our

Chess, and it may safely be said

that Go has nothing to fear from the comparison. Indeed, it is not too

much to

say that it presents even greater opportunities for foresight and keen

analysis. The Japanese also play Chess, which they

call "Shogi," but it

is slightly different from our Chess, and their game has not been so

well

developed. Go, on the other hand, has been zealously

played and scientifically

developed for centuries, and as will appear more at length in the

chapter on

the History of the Game, it has, during part of this time, been

recognized and

fostered by the government. Until recently a systematic treatment of

the game,

such as we are accustomed to in our books on Chess, has been lacking in

Japan.

A copious literature had been produced, but it consisted mostly of

collections

of illustrative and annotated games, and the Go masters seem to have

had a

desire to make their marginal annotations as brief as possible, in

order to

compel the beginner to go to the master for instruction and to learn

the game

only by hard practice. Chess and Go are both in a sense military

games, but the military

tactics that are represented in Chess are of a past age, in which the

king

himself entered the conflict — his fall generally meaning the loss of

the

battle — and in which the victory or defeat was brought about by the

courage of

single noblemen rather than through the fighting of the common soldiers. Go, on the other hand, is not merely a

picture of a single battle like

Chess, but of a whole campaign of a modern kind, in which the

strategical

movements of the masses in the end decide the victory. Battles occur in

various

parts of the board, and sometimes several are going on at the same

time. Strong

positions are besieged and captured, and whole armies are cut off from

their

line of communications and are taken prisoners unless they can fortify

themselves

in impregnable positions, and a far-reaching strategy alone assures the

victory. It is difficult to say which of the two

games gives more pleasure. The

combinations in Go suffer in comparison with those of Chess by reason

of a

certain monotony, because there are no pieces having different

movements, and

because the stones are not moved again after once being placed on the

board.

Also to a beginner the play, especially in the beginning of the game,

seems

vague; there are so many points on which the stones may be played, and

the

amount of territory obtainable by one move or the other seems

hopelessly

indefinite. This objection is more apparent than real, and as one's

knowledge

of the game grows, it becomes apparent that the first stones must be

played

with great care, and that there are certain definite, advantageous

positions,

which limit the player in his choice of moves, just as the recognized

Chess

openings guide our play in that game. Stones so played in the opening

are

called "Joseki" by the Japanese. Nevertheless, I think that in the

early part of the game the play is somewhat indefinite for any player

of

ordinary skill. On the other hand, these considerations are balanced by

the

greater number of combinations and by the greater number of places on

the board

where conflicts take place. As a rule it may be said that two average

players

of about equal strength will find more pleasure in Go than in Chess,

for in

Chess it is almost certain that the first of two such players who loses

a piece

will lose the game, and further play is mostly an unsuccessful struggle

against

certain defeat. In Go, on the other hand, a severe loss does not by any

means

entail the loss of the game, for the player temporarily worsted can

betake

himself to another portion of the field where, for the most part

unaffected by

the reverse already suffered, he may gain a compensating advantage. A peculiar charm of Go lies in the fact

that through the so-called

"Ko" an apparently severe loss may often be made a means of securing

a decisive advantage in another portion of the board. A game is so much

the

more interesting the oftener the opportunities for victory or defeat

change,

and in Chess these chances do not change often, seldom more than twice.

In Go,

on the other hand, they change much more frequently, and sometimes just

at the

end of the game, perhaps in the last moments, an almost certain defeat

may by

some clever move be changed into a victory. There is another respect in which Go is

distinctly superior to Chess.

That is in the system of handicapping. When handicaps are given in

Chess, the

whole opening is more or less spoiled, and the scale of handicaps, from

the

Bishop's Pawn to Queen's Rook, is not very accurate; and in one

variation of

the Muzio gambit, so far from being a handicap, it is really an

advantage to

the first player to give up the Queen's Knight. In Go, on the other

hand, the

handicaps are in a progressive scale of great accuracy, they have been

given

from the earliest times, and the openings with handicaps have been

studied

quite as much as those without handicaps. In regard to the time required to play a

game of Go, it may be said that

ordinary players finish a game in an hour or two, but as in Chess, a

championship game may be continued through several sittings, and may

last eight

or ten hours. There is on record, however, an authentic account of a

game that

was played for the championship at Yeddo during the Shogunate, which

lasted

continuously nine days and one night. Before taking up a description of the board and stones and the rules of play, we will first outline a history of the game. PREFACE INTRODUCTION I: HISTORY OF THE GAME II: DESCRIPTION OF THE BOARD AND STONES III: RULES OF PLAY IV: GENERAL METHODS OF PLAY AND TERMINOLOGY OF THE GAME V: ILLUSTRATIVE GAMES VI: "JOSEKI" AND OPENINGS VII: THE END GAME VIII: PROBLEMS |