| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

VII

THE END GAME A work on the game of Go would not be

complete without a

chapter especially devoted to the subject of the end game. On the average a game of Go consists of

about two

hundred and fifty moves, and we might say that about twenty of these

moves

belong to the opening, about one hundred and fifty to the main part of

the

game, and the remaining eighty to the end game. The moves which may be

regarded

as belonging to the end game are those which connect the various groups

of

stones with the margin, and which fill up the space between the

opposing groups

of stones. Of course, there is no sharp distinction between the main

game and

the end game. Long before the main game is finished moves occur which

bear the

characteristics of end game play, and as the game progresses moves of

this kind

become more and more frequent, until at last all of the moves are

strictly part

of the end game. Toward the end of the game it becomes

possible to

calculate the value of a move with greater accuracy than in the middle

of the

game, and in many cases the number of points which may be gained by a

certain

move may be ascertained with absolute accuracy. Therefore, when the

main game

is nearing completion, the players survey the board in order to locate

the most

advantageous end plays; that is to say, positions where they can gain

the

greatest number of "Me." In calculating the value of an end position,

a player must carefully consider whether on its completion he will

retain or

lose the "Sente." It is an advantage to retain the "Sente,"

and it is generally good play to choose an end position where the

"Sente" is retained, in preference to an end position where it is

lost, even if the latter would gain a few more "Me." The player holding the "Sente" would,

therefore, complete in rotation those end positions which allowed him

to retain

it, commencing, of course, with those involving the greatest number of

"Me." He would at last come to a point, however, where it would be

more advantageous to play some end position which gained for him quite

a number

of points, although on its completion the "Sente" would be lost. His

adversary, thereupon gaining the "Sente," would, in turn, play his

series of end positions until it became advantageous for him to

relinquish it.

By this process the value of the contested end positions would become

smaller

and smaller, until at last there would remain only the filling of

isolated,

vacant intersections between the opposing lines, the occupation of

which

results in no advantage for either player. These moves are called

"Dame," as we have already seen. This is the general scheme of an end game,

but, of

course, in actual play there would be many departures therefrom.

Sometimes an

advantage can be gained by making an unsound though dangerous move, in

the hope

that the adversary may make some error in replying thereto. Then again,

in

playing against a player who lacks initiative, it is not so necessary

to

consider the certainty of retaining the "Sente" as when opposed by a

more aggressive adversary. Frequently also the players differ in their

estimate

of the value of the various end positions, and do not, therefore,

respond to

each other's attacks. In this way the possession of the "Sente"

generally changes more frequently during the end game than is logically

necessary. The process of connecting the various

groups with the

edge of the board gives rise to end positions in which there is more or

less

similarity in all games, and most of the illustrations which are now

given are

examples of this class. The end positions which occur in the middle of

the

board may vary so much in every game that it is practically impossible

to give

typical illustrations of them. Of course, in an introductory work of this

character

it is not practicable to give a great many examples of end positions,

and I

have prepared only twelve, which are selected from the work of Inouye

Hoshin,

and which are annotated so that the reasons for the moves may be

understood by

beginners. The number of "Me" gained in each case is stated, and also

whether the "Sente" is lost or retained. To these twelve examples I

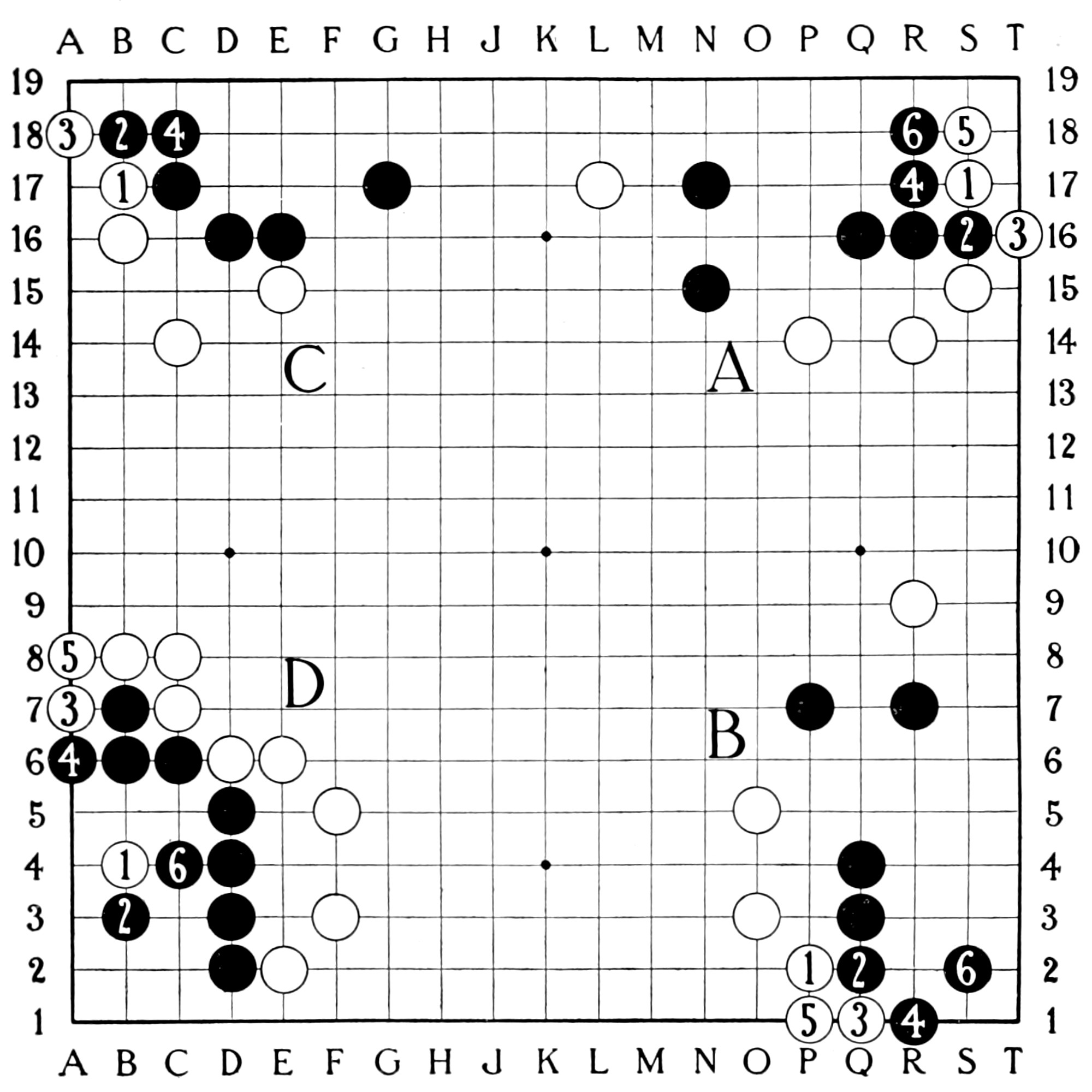

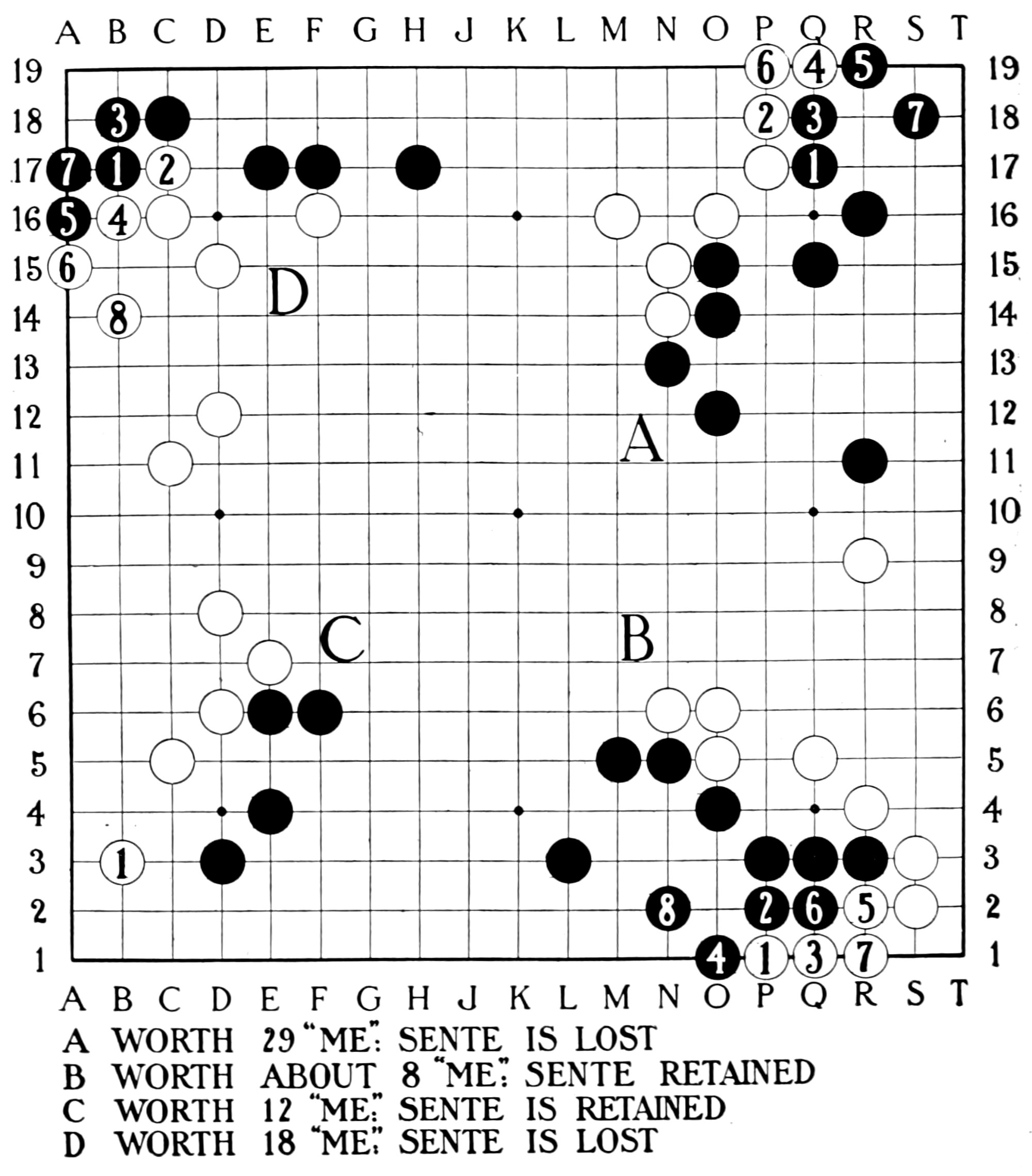

have added eight positions from Korschelt's work. Plate 35 (A) The following stones are on the board:

White,

S 15, R 14, P 14, L 17; Black, R 16,

Q 16,

N 15, N 17. If White has the "Sente," he gains eight

"Me," counting together what he wins and Black loses.

Plate 35

White retains the "Sente." II Plate 35 (B) The following stones are on the board:

White,

R 9, O 5, O 3; Black, P 7, Q 3, Q 4,

R 7. If White has the first move, it makes a

difference of

six "Me."

White retains the "Sente." If Black had had the first move, the play

would have

been as follows:

Plate 35 (C) The following stones are on the board:

White,

B 16, C 14, E 15; Black, C 17, D 16,

E 16,

G 17. If White has the move, it makes a

difference of seven

"Me."

Plate 35 (D) The following stones are on the board:

White,

B 8, C 7, C 8, D 6, E 2, E 6, F 3,

F 5;

Black, B 6, B 7, C 6, D 2, 3, 4, 5. If White has the move, it makes a

difference of four

"Me."

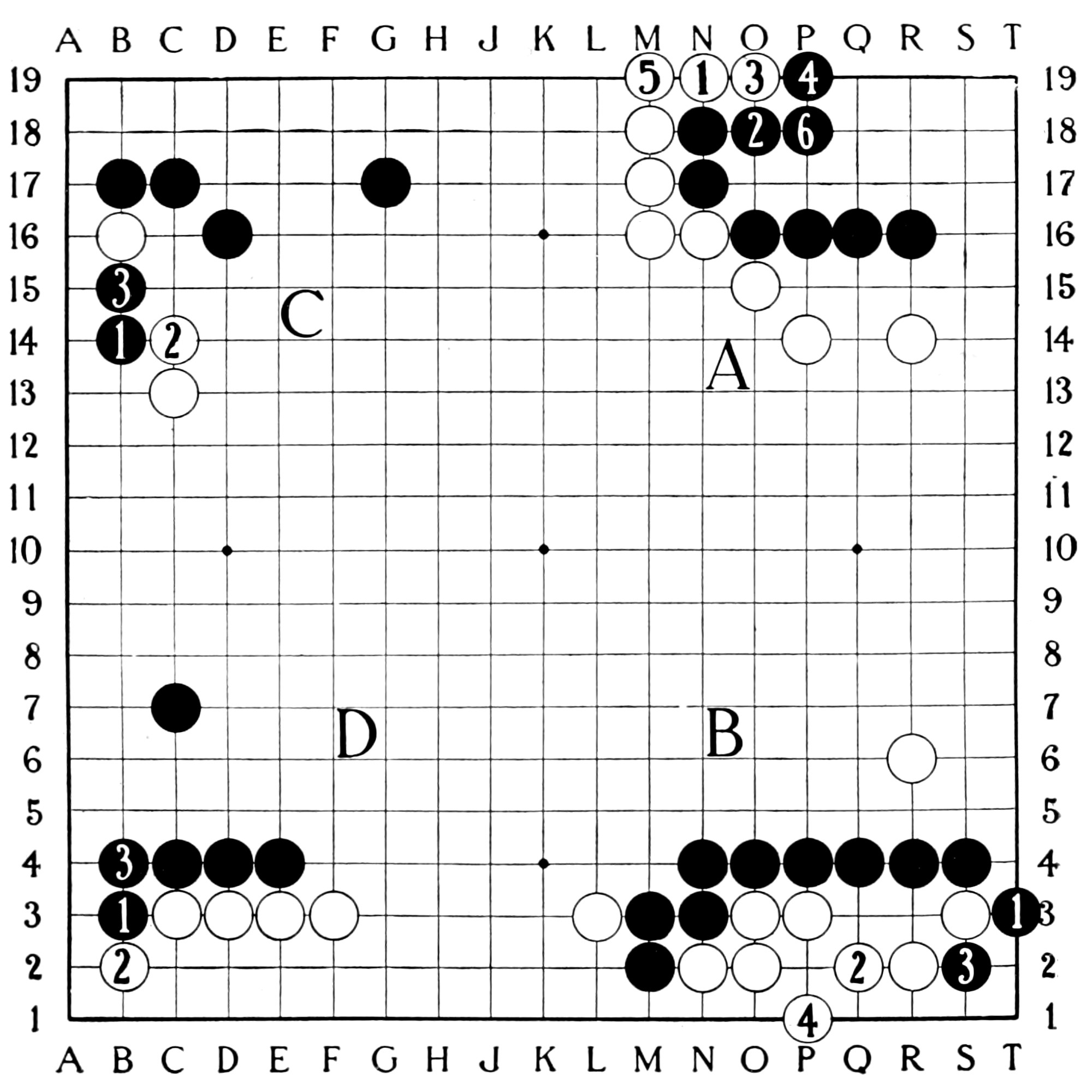

Plate 36 (A) If White has the "Sente," it makes a

difference

of six "Me."

Plate 36 (B) The following stones are on the board:

Black,

M 2, M 3, N 3, N 4, O 4, Q 4, R 4,

S 4;

White, L 3, N 2, O 2, O 3, P 3, R 2,

S 3,

R 6. Black has the "Sente" and gains

nine "Me."  Plate 36

Plate 36 (C) The following stones are on the board:

Black,

B 17, C 17, D 16, G 17; White, B 16,

C 13.

VIII Plate 36 (D) The following stones are on the board:

Black,

C 4, D 4, E 4, C 7; White, C 3, D 3,

E 3,

F 3. Black has the move.

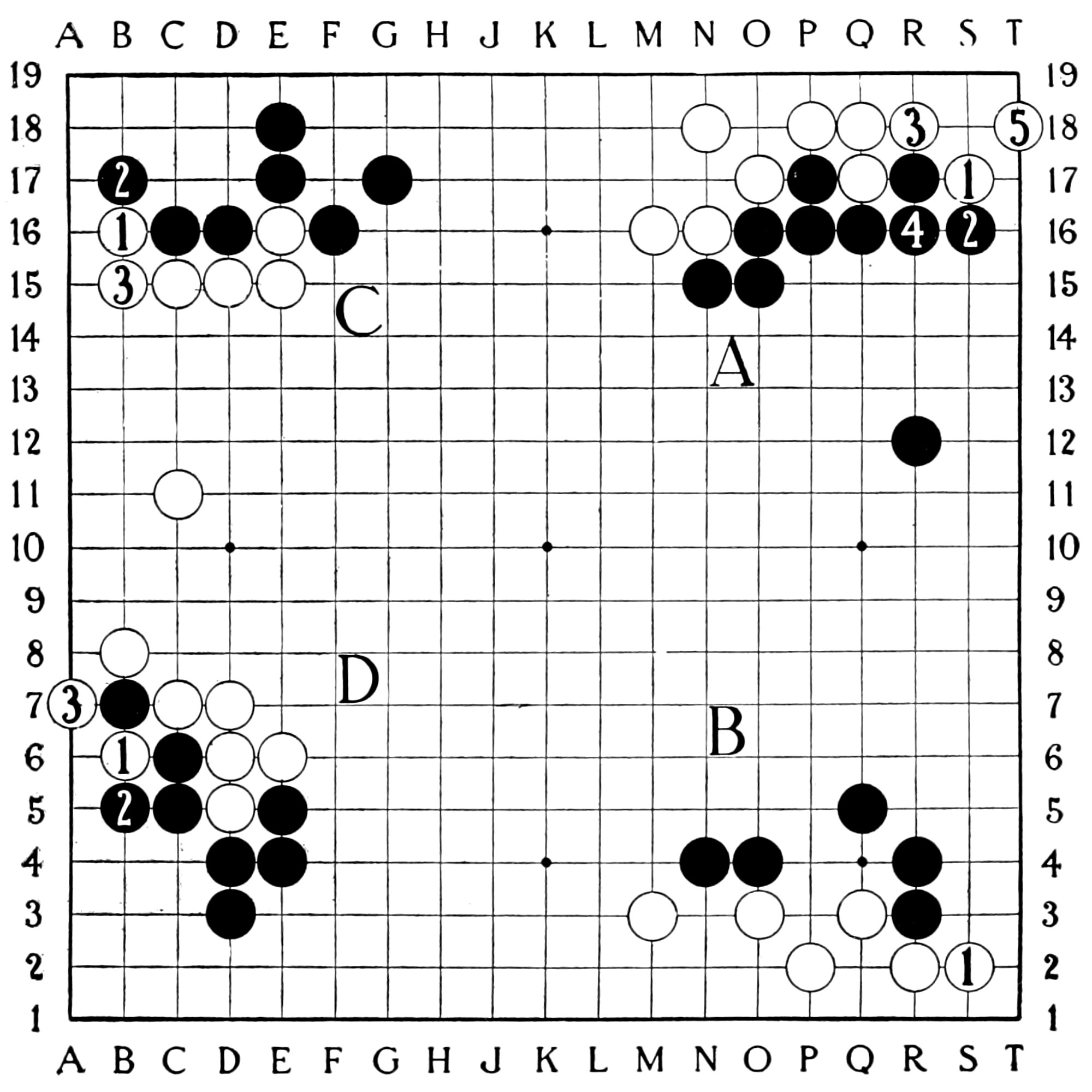

Plate 37 (A) The following stones are on the board:

White,

M 16, N 16, N 18, O 17, P 18, Q 17, 18;

Black,

N 15, O 15, 16, P 16, 17, Q 16, R 12,

R 17.

White has given up the "Sente," but these

moves make a difference in his favor of about fourteen "Me." Plate 37 (B) The following stones are on the board:

White,

M 3, O 3, P 2, Q 3, R 2; Black, N 4,

O 4,

Q 5, R 3, R 4. White has the move.

This move is really "Go te," but if Black

neglects to answer it, White can then jump to T 5. This jump is

called by

a special name "O zaru," or the "big monkey," and would

gain about eight "Me" for White. Plate 37 (C) The following stones are on the board:

White,

C 15, D 15, E 15, 16; Black, C 16, D 16,

E 17,

18, F 16, G 17. White has the move.

Plate 37 XII Plate 37 (D) The following stones are on the board:

White,

B 8, C 7, 11, D 5, 6, 7, E 6; Black, B 7,

C 5, 6,

D 3, 4, E 4, 5. White has the move.

White has given up the "Sente," but this

method of play gains about fourteen "Me," as it is now no longer

necessary to protect the connection at C 8. We will now insert two plates from

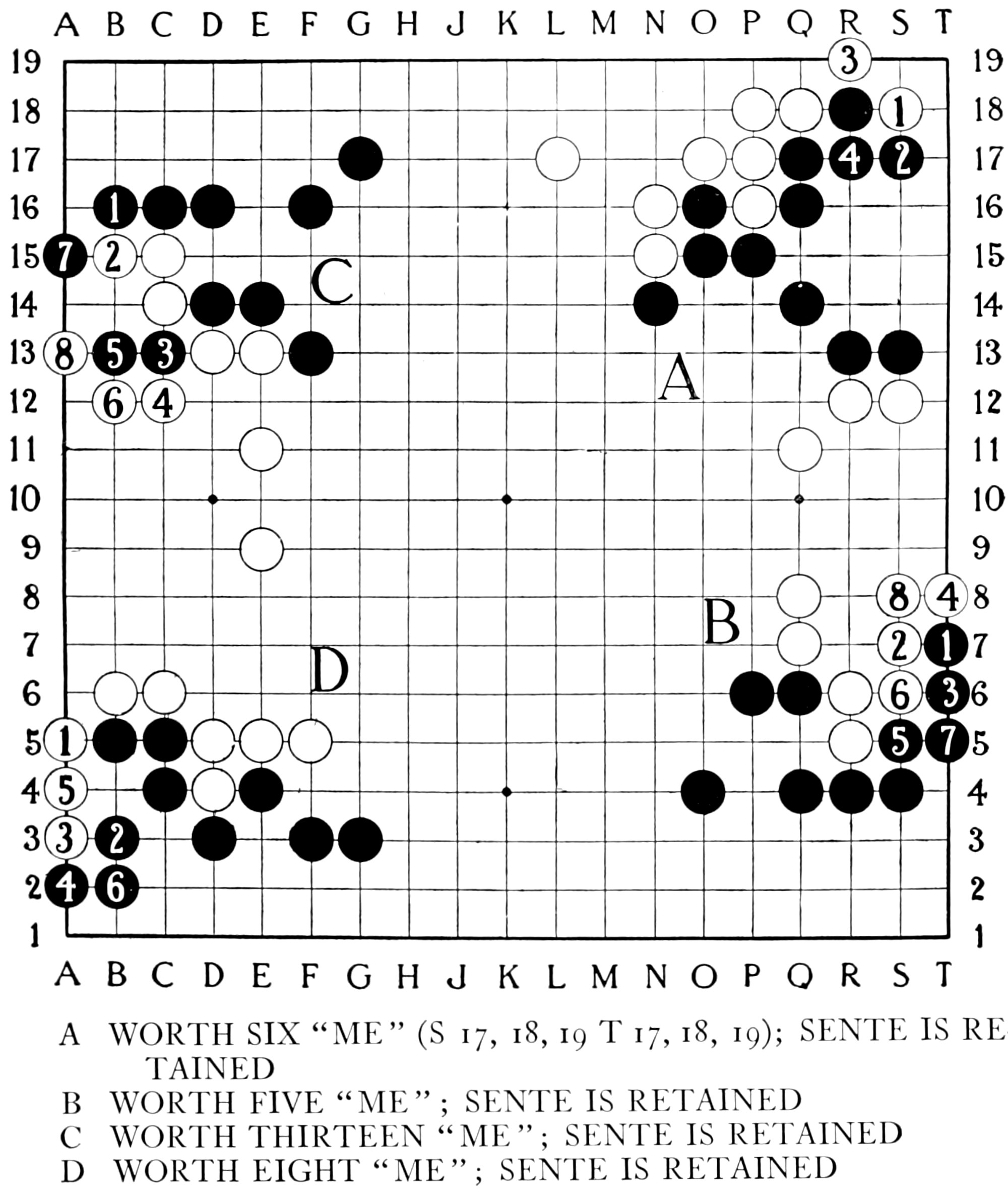

Korschelt's book.

The notes at the foot of the illustrations are his.  Plate 38  Plate 39 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||