CHAPTER

XIX

THE

PRESENT POSITION OF THE PROBLEM

"Do

not be afraid of making

generalisations because knowledge is as yet imperfect or incomplete,

and they

are therefore liable to alteration. It is only through such

generalisations

that progress can be made." — Dr. A. C. Haddon as President of

the Folk

Lore Society, 1919.

As we

leave Easter Island, we pause to review our evidence and find how far

we have

progressed towards the solution of its problems.

We may

dismiss the vague suggestion that the archaeological remains in the

island

survive from the time when it was part of a larger mass of land.

Whatever may

be the geological story of the Pacific, no scientific authorities are

prepared

to prove that such stupendous changes have taken place during the time

which it

has been inhabited by man.1

Instead

of indulging in surmises as to the state of the world in a remote past,

it is

safer to begin with existing conditions and try to retrace the steps of

development . It has already been seen that various links connect the

people

now living on Easter Island with the great images. Tradition is not

altogether

extinct; in a few cases the names of the men are actually remembered

who made

the individual statues, and also those of their clans, which are still

in

existence. But the two strongest bonds are the wooden figures and the

bird-cult. The wooden figures were being made in recent times, and they

have a

design on the back resembling that on the stone images, while they also

possess

the same long ears. There is no reason why a defunct type should have

been

copied, and it is probable that they date at least as far back as the

same

epoch. The bird-cult also was alive in living memory. It is allied to

that of

the statues by the residence of the bird-man among the images, by the

fact that

the bird rite for the child was connected with them, and above all by

the

presence of a statue of typical form in the centre of the village at

Orongo.

Assuming

then, at any rate for the sake of argument, that the stone figures were

the

work of the ancestors of the people of to-day, the next step is to

inquire who

these people are. Here for a certain distance we are on firm ground.

They are

undoubtedly connected with those found elsewhere in the Pacific; much

of their

culture is similar; and even the earliest voyagers noted that their

language

resembled that found on the other islands. The suggestion that Easter

Island

has been populated from South America may therefore, for practical

purposes, be

ruled out of the question. If there is any connection between the two,

it is

more likely that the influence spread from the islands to the

continent.

Having

reached this point, however, we are faced by the larger problem. Who

were the

race or races who populated the Pacific? Here our firm ground ends, for

this is

a very complicated subject, with regard to which much work still

remains to be

done. It is impossible as yet to make any broad statement, which is not

subject

to qualification, or which can be implicitly relied on.

The

Solomon group and other islands off the coast of Australia are

inhabited by a

people known as Melanesians, who have dark skins, fuzzy hair, and thick

lips,

resembling to some extent the natives of Africa; this area is called

Melanesia.

Certain outlying islets are, however, populated by a different race,

who

possess straight or wavy hair and fairer skins. Eastward of a line

which is

drawn at Fiji this whiter race, called Polynesian, predominates, and

the

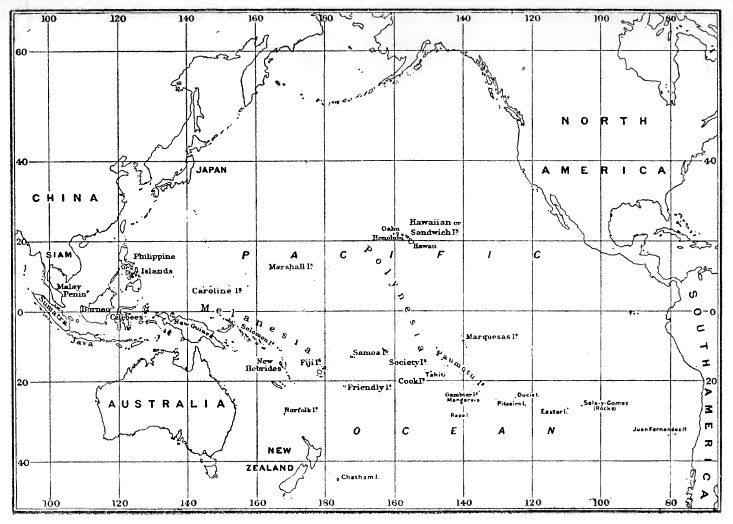

eastern part of the Pacific is known as Polynesia.

Broadly

speaking, the theory generally accepted has been that negroid people

are the

earliest denizens, and that the lighter race came down into Melanesia

through

the Malay peninsula, and thence passed on through Melanesia in a

succession of

waves. A large proportion of the invaders were probably of the male

sex, and

took wives from amongst the original inhabitants. They absorbed in many

ways

the culture of the older people, but did not wholly abandon their own.

It is

suggested, for instance, that while as a whole the conquerors adopted

existing

religions, the secret societies, so often found in the Pacific, are

connected

with their own rites and beliefs, which were guarded as something

sacred and

apart.

It will

easily be seen that the task of tracing these migrations is by no means

simple.

Canoes, carrying fighting men or immigrants, bent on victory or

colonisation,

passed continually from one island to another, and each island has

probably its

own very complicated history. The Maoris of New Zealand, for example,

are a

Polynesian race, but there are also traces there of a darker people.

Absolutely

negroid elements are found as far east as the Marquesas. Our servant

Mahanga,

whose features are of that type, came from the Paumotu Islands (fig.

89).

The

marvellous feats of seamanship performed in these wanderings, often

against the

prevailing trade wind, would be incredible if it were not obvious that

they

have been actually accomplished. The loss of life was doubtless very

great, and

many boats must have started forth and never been heard of more. The

fact

remains, however, that native canoes have worked their way over unknown

seas as

far north as the Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands, and that somehow or

other they

reached that little spot in the waste of waters now known as Easter

Island. The

nearest land to Easter now inhabited, with the exception of Pitcairn

Island, is

in the Gambler Islands, about 1,200 miles to the westward; the little

coral

patch of Ducie Island, which lies between the two, is nearly 900 miles

from

Easter, and has no dwellers. It has been suggested that the original

immigrants

may have intended to make a voyage from one known island to another and

have

been blown out of their course. However this may be, a long voyage must

have been

foreseen, or the boats would not have carried sufficient provisions to

reach so

distant a goal. It is even more strange to realise that, if the mixture

of

races found among the islanders occurred after their arrival, more than

one

native expedition has performed the miracle of reaching Easter Island.

The

traditions of the present people do not, as has been seen, give very

material

assistance as to the composition of the crew nor how they reached the

island.

They tell us that their ancestors were compelled to leave their

original home

through being vanquished in war. This was a very usual reason for such

migrations, as the conquered were frequently compelled to choose

between

voluntary exile or death; but to account for the discovery of the

island they are

obliged to take refuge in the supernatural and explain that its

whereabouts

were revealed in a dream. The story of Hotu-matua gives no suggestion

that the

island was already inhabited, save for one very vague hint. The six men

who

formed the first detachment of the party were told that the island as

revealed

in the dream possessed not only a great crater, but also “a long

beautiful

road." The Long Ears, who according to tradition were exterminated by

the

Short Ears, may have been an earlier race, but it cannot be claimed

that the

story tells us so. The two peoples are represented as coming together,

or as

living side by side on the island. The whole account is rendered more

puzzling

by the fact that, while the Short Ears are said to have been the

ancestors of

the present people, the fashion of making long the lobe of the ear

prevailed on

the island till quite recently.

It is

noteworthy, however, that a legend exists elsewhere which definitely

reports

that the later comers did find an earlier people in possession.

According to

the account of Admiral T. de Lapelin,2 there is

a tradition at

Mangareva in the Gambler Islands to the effect that the adherents of a

certain

chief, being vanquished, sought safety in flight; they departed with a

west

wind in two big canoes, taking with them women, children, and all sorts

of

provisions. The party were never seen again, save for one man who

subsequently

returned to Mangareva. From him it was learned that the fugitives had

found an

island in the middle of the seas, and disembarked in a little bay

surrounded by

mountains; where, finding traces of inhabitants, they had made

fortifications

of stone on one of the heights. A few days later they were attacked by

a horde

of natives armed with spears, but succeeded in defeating them. The

victors then

pitilessly massacred their opponents throughout the island, sparing

only the

women and children. There are now no stone fortifications visible at

Anakena,

but one of the hill-tops to the east of the cove has, for some reason

or other,

been entrenched (fig.96.)

Turning

to more scientific evidence, we find that the Islanders have always

been judged

to be of Polynesian race, as indeed would naturally be expected from

the

easterly position of the island in the Pacific Ocean. They have

certainly

traces of that culture, and the great authority on the subject, Mr.

Sydney Ray,

has pronounced the language to be Polynesian. The surprise, therefore,

which

the results of the expedition have brought to the anthropological

world, is the

discovery of the extent to which the negroid element is found to

prevail there

both from the physical and cultural points of view.

Melanesian

skulls are mainly of the long-headed type, while Polynesian are

frequently

broad-headed. A collection of fifty-eight skulls was brought back from

Easter

and examined by Dr. Keith. He says in his report: "The Polynesian type

is

fairly purely represented in some of the Easter Islanders, . . . but

they are

absolutely and relatively a remarkably long-headed people, and in this

feature

they approach the Melanesian more than the Polynesian type." A similar

statement was quite independently made to the Royal Geographical

Society on

this head. In the discussion which followed the reading of a paper on

behalf of

the Expedition, Capt. T. A. Joyce of the British Museum, remarked that

a few

years ago he had examined the skulls brought back from Easter Island by

the

late Lord Crawford. “I then," he continued, “wrote a paper which I

never

published. It remained both literally and metaphorically a skeleton in

my

cupboard, because I could not get away from the conclusion that in

their

measurements and general appearance these skulls were far more

Melanesian than

Polynesian."3 In speaking of skulls, Dr. Keith

makes the

interesting remark that the Islanders are the largest-brained people

yet

discovered in the islands or shores of the Pacific, and shows that

their

cranial capacity exceeds that of the inhabitants of

Whitechapel.

In the

culture of the island also, the Melanesian influence is very strong.

The custom

of distending the lobe of the ear is much more Melanesian than

Polynesian. Dr.

Haddon has pointed out that an early illustration of an Easter Island

canoe

depicts it with a double outrigger, after a type found in the Nissan

group in

Melanesia.4 An obsidian blade has been found in

the area of New

Guinea influenced by Melanesian culture, which has been described and

figured

by Dr. Seligman5; he draws attention to its

striking likeness to the

mataa of Easter Island. Weapons of the same type, and wooden figures in

which

the ribs are a prominent feature, have been found in the Chatham

Islands,6

but the respective amount of Polynesian and Melanesian culture in these

islands

is as yet under discussion.

The most

striking evidence is, however, found in connection with the bird-cult.

It has

been shown by Mr. Henry Balfour that a cult with strong resemblance to

that of

Easter existed in the Solomon Islands of Melanesia. It is there

connected with

the Frigate bird, a sea-bird which usually nests in trees and is

characterised

by a hooked beak and gular pouch. In treeless Easter Island the sacred

bird is

the Sooty Tern, which is without the gular pouch and has a straight

beak. In

many of the carvings on the island, however, the sacred bird is

represented with

a hooked beak and a pouch (fig. 112). “This seems to point to a

recollection

retained by the immigrants into Easter Island of a former cult of the

Frigate-bird which was practised in a region where this bird was a

familiar

feature, and which was gradually given up in the new environment when

this

bird, though probably not unknown, was certainly not abundant7;

the

cult being transferred to the locally numerous Tem.

Figures

were also made in the Solomon Islands composed partly of bird and

partly of

human form. Bird heads appear on human bodies, as in Easter Island, and

also

human heads on bird bodies (fig. 125). It is noteworthy that, even when

the

head which is drawn on the bird body is human, it is depicted with

bird-like

characteristics, the lower part of the face being given a beak-like

protrusion,

till sometimes it is almost impossible to distinguish whether the head

is that

of a man or a bird (no. 6). This prognathous type, with the protrusion

of the

lower facial region, appears to have become a convention, and it is

found in

figures where the body as well as the head are human (no. 7). This is

the kind

found in a modified form in the Easter Island stone figures; they

differ from

any normal human type in either Polynesia

or Melanesia.

|

|

BIRD

AND HUMAN

DESIGNS.

1,2,3,4

from the

Solomon Islands

1a,

2a, 3a, 4a

from the script, Easter Island.

BIRD

HEADS AND

HUMAN BODIES.

5.

Wooden float

for fishing net. Solomon Islands.

5a.

Painting on

Orongo house, Easter Island.

HUMAN

HEADS WITH BIRD CHARACTERISTICS.

6.

On a bird

body. Float for net. Solomon Islands.

7.

On a human

body. Canoe-prow god, Solomon Islands.

8.

Profile of a

stone statue, Easter Island. |

|

|

FIG. 125. —

BIRD-HUMAN FIGURES IN THE SOLOMON ISLANDS AND EASTER

ISLAND.

Selected from

the figures illustrating an article by H. Balfour, Curator of the

Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford. Folk Lore, December

1917 |

It is

impossible as yet to give with any certainty a connected account of the

early

history of Easter Island, but as a working hypothesis the following may

perhaps

be assumed. There was an original negroid element which brought with it

the

custom of distending the ear, the wooden figures, and also the

bird-cult. A

whiter wave succeeded which mingled with the first inhabitants, and the

next

generation adopted the fashion of the country in stretching the lobe of

the

ear, and carried on the bird-cult. At some time in the course of

settlement war

arose between the earlier and later comers, in which the former took

refuge in

the eastern headland and were largely exterminated.

If these

suppositions are so far correct, the story of the landing of Hotu-matua

and the

establishment of his headquarters at Anakena refer to the Polynesian

immigration, and it seems reasonable to look to the Miru, who are

settled in

that part of the island, and perhaps also to the allied clans of the

Marama and

Haumoana, who together form the chief inhabitants of the district of

Kotuu, as

the more direct descendants of the Polynesian settlers. In confirmation

of this

we find that the ariki, or chief, the only man who was necessarily of

pure descent,

is said to have been "quite white.” The inscribed skulls, which are

those

of the Miru, are reported to be of the Polynesian type. It is a some

what

striking fact also that the ariki, in spite of his prominent position

in the

island, took no part in the bird-cult ceremonies.

In

endeavouring to arrive at even an approximate date for these

immigrations to

the island, evidence outside its borders is likely to prove our best

guide. In

the present state of our knowledge we cannot even guess how long the

negroid

element has been in the Pacific, but the lighter races are believed to

have

entered it not earlier than the Christian era. The colonisation of the

Paumotus

is placed at A.D. 1000,8 and it has been

suggested by Volz that the

Polynesian wave reached Easter Island about A.D. 1400.

There is

at present no evidence to show whether the great works were initiated

by the

earlier or the later arrivals. There are other megalithic remains in

the Pacific,

notably great walls of stone in the Caroline Islands. The Expedition

found a

stone statue in Pitcairn,9 but we have as yet no

complete

information with regard to these works or the circumstances of their

construction. The Polynesians are accredited with having carried with

them the

fashion of erecting such monuments, but, if they brought it to Easter

Island,

the form which it took was apparently governed by conventions already

existing

in the island.

On the

other hand, it seems possible that the makers of the images may have

come from

a country where they were accustomed to model statues in wood, and

finding no

such material in the island, substituted for it the stone of Raraku.

Sir Basil

Thomson has pointed out that there were in the Marquesas wooden statues

standing on erections of stone and also wooden dolls. Further knowledge

of what

exists elsewhere will probably throw light on the matter, but it is, in

any

case, owing to the fact that there is to be found at Easter a volcanic

ash

which can be easily wrought that we have the hundreds of images in the

island.

With

regard to the duration of the image era, it has been shown that the

number of

statues, impressive as it is, does not necessarily imply that their

manufacture

covered a vast space of time. It must, however, in all probability have

extended over several centuries. As to its termination, the worship is

reported

as having been in existence in 1722; at any rate the ahu and statues

were then

in good repair. By 1774 some of the statues had fallen, and by about

1840 none

remained in place. It seems, therefore, on the whole, most likely that

the

cult, and probably also the manufacture of the images, existed till the

beginning of the eighteenth century. The alternative explanation can

only be

that though the cult had long been dead the statues remained in place,

not

materially injured either by man or weather, until Europeans first

visited the

island, and that then an era of devastation set in which in a hundred

years

demolished them all. This, though not actually impossible, does not

seem

equally probable.

We know

that a large number, probably the majority, of the statues came to

their end

through being deliberately thrown down by invading enemies. The

legendary

struggles between Kotuu and Hotu Iti, in which Kainga played so

prominent a

part, are always spoken of as comparatively recent history, and one old

man

definitely asserted that they took place in the time of the grandfather

of the

last ariki, which may be as far back as the eighteenth century. If

these wars

occurred between the visit of the Dutchmen in 1722 and that of the

Spaniards in

1770, it is at least possible that it was during their course that the

manufacture of the images ended and their overthrow began. It will be

remembered that, while Roggeveen speaks of the island as cultivated and

fertile, the navigators fifty years later are greatly disappointed with

the

barren condition in which they find it. In the curious absence,

however, of any

reference in these legends to the conditions of the images, this must

remain,

for the present at any rate, as surmise only.

It would

be interesting to know more clearly the part played by the advent of

the white

men in the evolution of the culture of the island. While it cannot be

definitely stated that it was their arrival which, by detracting from

the

reverence paid to the statues, hastened their downfall, we know that it

largely

affected native conceptions. Not only was it the probable cause of the

abandonment at the end of the eighteenth century of the practice of

distending

the lobe of the ear,10 but it inspired a new

form of worship. It is

interesting to see in the drawings of foreign ships, which appear side

by side

with older designs, a new cult actually in course of intermingling with

the old

forms. Did we not possess the key to them, these pictures would add one

more to

the mysteries of the island.

Such

evidence as can be obtained from the condition of the images points to

the fact

that it cannot be indefinite ages since they were completed. For

example, in

certain statues, those which are generally considered the most recent,

the

surface polish still remains in its place in the cavity representing

the eye,

and on parts of the neck and breast where it has been somewhat

sheltered by the

chin, notwithstanding the fact that the soft stone is one that easily

weathers (Frontispiece).

The

question as to what the statues represent is not yet fully solved. It

seems

probable that the form was a conventional one and was used to denote

various

things. Some of the statues may have been gods; the name of a single

image on

an inland ahu, one of the very few which were remembered, was reported

to be

"Moai Te Atua." It is, however, probably safe to regard ahu statues

as being in general representations of ancestors, either nearer or more

distant, this does not necessarily exclude the idea of divinity. The

hat may

have been a badge of rank; warriors in Tahiti wore a certain type of

hat as a

special mark of distinction.11 Reasons have been

given for

suggesting that the images on Raraku may have been memorials of bird

men; and

we know that some of the statues, as those on the southern slope of

Raraku and

in Motu Nui, denoted boundaries. Lastly, it is not impossible that some

of the

figures, such as those approaching the ahu of Paukura, were simply

ornamental,

“to make it look nice." The nearest approach which we ourselves have to

such divers employment of the same design is in our use of the Latin

cross.

Fundamentally a sacred sign, it is used not only to adorn churches and

for

personal ornament, but also to mark graves and denote common and

central

grounds, such as the site of markets and other public places. It is

also used

to preserve the memory of certain spots, as for instance, Charing

Cross, where

the body of Queen Eleanor rested.

The last

problem to be considered is that dealing with the tablets. An account

has been

given elsewhere of what is known of their general meaning. The figures

themselves may be classed as ideograms — that is, signs representing

ideas —

but it is doubtful, as has been shown, if a given sign always

represented the

same idea. Each sign was in any case a peg on which to hang a large

amount of

matter which was committed to memory, and is therefore, alas! gone for

ever.

No light

has yet been thrown on the origin of the script. No other writing has

been

found in the Pacific, if we except a form from the Caroline Islands,

and a few

rock carvings in the Chatham Islands, whose connection with the glyphs

of

Easter Island is as yet very doubtful.

It would

be satisfactory, in view of the relation of the Miru ariki to the

tablets, and

the tradition that they came with Hotumatua, if internal evidence could

show

that it was of Polynesian origin. Unfortunately for this theory, the

Melanesian

bird figures largely among the signs. It is, of course, conceivable

that they

may have undergone local adaptation. While it is not probable that we

shall

ever be able to read the tablets, it is not impossible that further

discovery

may throw light on the history of the signs, and show to what extent

the script

has been imported from elsewhere, or how far it is, with much of its

other

culture, a product of the isolation of Easter Island.

1

Theosophists, indeed, contend that it has been revealed by occult means

that Easter

Island is the remaining portion of an old continent named "Lemuria,"

which occupied the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and the writer has been

informed

by correspondents that she "may be interested to learn" that such is

the case. Representations even of the world at this remote epoch have

been, it

is said, received by clairvoyance and are reproduced in theosophical

literature: in the case of a later continent of Atlantis, which has

also

disappeared, it was permitted to see its proportions on a globe and by

other

means; but, unfortunately, in the case of Lemuria, “there was only a

broken

terra-cotta model and crumpled map, so that the difficulty of carrying

back the

remembrance of all the details, and consequently of reproducing exact

copies,

has been far greater" (The Lost

Lemuria, Scott Elliot, p. 13). The world at the Lemurian

epoch was, we are

informed, inhabited by beings who were travelling for the fourth time

through

their round of the planets, and undergoing for the third time their

necessary

seven incarnations on the earth during this round. At the beginning of

this

third race of the fourth round, man first evolved into a sexual being,

and at

the end was highly civilised. The makers of the Easter Island statues

were of

gigantic size. To prove this last point, Madame Blavatsky quotes a

statement to

the effect that "there is no reason to believe that any of the statues

have been built up bit by bit," and proceeds to argue that they must

consequently have been made by men of the same size as themselves. She

states

that the "images at Ronororaka — the only ones now found erect — are

four

in number"; and gives the following account of the head-dress of the

statues, “a kind of flat cap with a back piece attached to it to cover

the back

portion of the head" (Secret

Doctrine, vol, ii. p. 337). The readers of this book can

judge of the

correctness of these descriptions. Theosophists must forgive us, if, in

the

face of error as to what exists to-day, we decline to accept without

further

proof information as to what occurred "nearer four million than two

million years ago."

2 Revue

Maritime et Coloniale, vol. xxxv.

(1872), p. 108, note. It is unfortunate that M. de Lapelin does not

give us

more details as to when and from whom the account was received.

3 Royal

Geographical Journal, May 1917. It

has been pointed out that Dr. Hamy, examining skulls from Easter Island

some

thirty years ago, and W. Volz (Arch. f.

Anth. xxiii. 1895, P97 ff.) attained the same result. Mr.

Pycraft also came

independently to the same conclusion.

4 Folk

Lore. June 1918, p. 161.

5 Man,

1918, No. 91, pi. M. Also in Anthropological

Essays, presented to E.

B. Tylor, 1907, pi. iii. fig. 2, and p. 327.

6 H.

Balfour, Man, Oct. 1918, No. 80. Folk Lore,

Dec. 1917, pp. 356-60.

7 H.

Balfour, Folk Lore, Dec. 191 7. For

full particulars of this and the following points readers are referred

to the

paper itself.

8 Hawaii,

S. Percy Smith, p. 294.

9 See Chapter

XX, section on Pitcairn Island.

10 If it

were not that the strife between the Long and Short Ears is always

placed in

very remote ages, we might be tempted to see in it a struggle between

the

adherents of the older and newer fashion. In the Hawaiian Islands such

a combat

took place before the advent of Christianity, see Chapter XXI, section

on the Hawaiian

Island.

11 Quest

and Occupation of Tahiti, Hakluyt

Society, vol. ii. p. 270.

|